Billy Joel said it best:

“I’d rather laugh with the sinners than cry with the saints/the sinners are much more fun.”

For me, the same is true for protagonists.

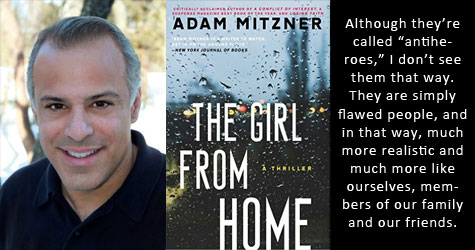

Although they’re called “antiheroes,” I don’t see them that way. They are simply flawed people, and in that way, much more realistic and much more like ourselves, members of our family and our friends.

Perhaps the most common question I get about my writing process is: “How do you start?”

Most readers assume it’s with the crime or the twist at the end. However, for me, it’s always with the characters. The question I ask myself before the first word is written is: “Who am I writing about and what’s his or her particular struggle?” Everything flows from there.

In my first book, A Conflict of Interest, I wrote about a man who was on the path to success, and then through a series of bad decisions, lost his way. For my sophomore effort, A Case of Redemption, I started out the other way—focusing on a character that had lost everything before the book opens, and was trying find his way back. Losing Faith is about a man who has reached the pinnacle of his professional career, and explores how fragile such a high perch can be and the lengths he and those who love him will go to hold on to it. Finally, in my most recent book, The Girl from Home, the protagonist is a man who’s willing to do whatever it takes to get what he wants, and through the course of the novel, he’s confronted with the price to be paid for such life choices and whether he’s capable of changing his ways.

In my first book, A Conflict of Interest, I wrote about a man who was on the path to success, and then through a series of bad decisions, lost his way. For my sophomore effort, A Case of Redemption, I started out the other way—focusing on a character that had lost everything before the book opens, and was trying find his way back. Losing Faith is about a man who has reached the pinnacle of his professional career, and explores how fragile such a high perch can be and the lengths he and those who love him will go to hold on to it. Finally, in my most recent book, The Girl from Home, the protagonist is a man who’s willing to do whatever it takes to get what he wants, and through the course of the novel, he’s confronted with the price to be paid for such life choices and whether he’s capable of changing his ways.

What makes these characters interesting to me is that, like myself (and I suspect my readers), each wants to be a good person—to live a moral life—and yet, temptations threaten to divert them from that path. How they handle these situations—sometimes succumbing, sometimes overcoming—and how they confront their own shortcomings is, to me, what defines a person.

The trick in writing these characters is to have the reader invested in their success, even if they’re also repulsed by their conduct. It’s not easy, but I know I’ve succeeded when I get a reader who says, “I was so mad when your character did…”

The protagonist of my latest book, Jonathan Caine, is a hedge fund manager in Manhattan who has everything, enjoying the life of the rich and famous, which, of course, includes a trophy wife, a penthouse with a view of the Statue of Liberty, and a $250,000 car. But, he wants more. In fact, the credo he lives by is: I want what I want.

This desire for more is something with which everyone can identify. There’s always the next thing that people feel they need to make their lives complete, whether it’s losing those last ten pounds, or the next promotion, or a beach house. When you see that kind of need on a grand scale, it’s comical—Jonathan cannot possibly live without an oceanfront home in East Hampton, and oceanfront anywhere else is unacceptable—and yet, many people have similar “must-haves” in their lives that, in reality, are things they can certainly live without and still be happy.

At least at first blush, Jonathan is not a likeable person, and early on in the writing, I was concerned that readers might not become sufficiently invested in his plight. However, I took comfort in the fact that popular culture has no shortage of compelling characters these days who are hardly paragons of virtue—from Walter White in Breaking Bad to Don Draper in Mad Men to my own favorite, Batman. There’s something compelling about witnessing morally compromised people attempt to justify their choices and, perhaps, learn from their mistakes.

Without giving away any spoilers, the plot of The Girl From Home concerns Jonathan’s fall and his efforts to start anew in the most unlikely of places—his hometown, where he’s returned to care for his ailing father and attend his twenty-fifth high school reunion. At the reunion, he becomes reacquainted with former prom queen, Jacqueline Williams. Jonathan can see a future with Jackie, but there are many roadblocks to that happy ending, not the least of which is Jackie’s jealous and abusive husband. But also standing in Jonthan’s way is his own nature. Is Jackie just another example of wanting what he wants, or is he capable of redemption?

In writing, the question that I kept returning to was whether Jonathan was capable of any type of transformation. A variation of the age-old question: “Can people really ever change?”

Perhaps it’s the romantic in me, but I like to think the answer is YES! That anyone with the desire to lead a better life can do so, without regard to whatever has happened before.

In economics, there’s a term for it: sunk costs—which posits that prior expenditures made in a venture should not contribute to the decision about the wisdom of future investment. The same could be true for life choices. Just because you’ve led your life a certain way doesn’t mean you have to continue living it that way. But like with sunk costs, many people feel that past is prologue, and they cannot envision living a life that might be radically different than the one they’re leading.

All of my protagonists face this dilemma in one way or another, with varying degrees of success. But then again, maybe that’s true of all of us, too.

To learn more or order a copy, visit:

Adam Mitzner, a lawyer by day, is the author of Losing Faith, A Case of Redemption, and A Conflict of Interest. He lives with his family in New York City.

Let’s hope that people can change or at least change their minds occasionally. If it weren’t for flaws and conflict, reading would be dull indeed.

We all might be antiheroes.