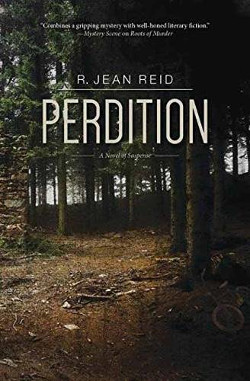

In Perdition by R. Jean Reid, a town and a mother are forced to confront their worst fears (available June 8, 2017).

What happens when a killer who can’t be caught threatens to kill your children next?

Newly widowed mother Nell McGraw struggles with her outsider status as she runs the newspaper founded by her husband’s grandfather. But a paper can’t turn away from the stories that others ignore, like the body of a child found in the Gulf. At first it seems tragic, a child lost because of carelessness.

Then another child goes missing.

Disgusted by the turf war between the sheriff and the police chief, Nell barely manages to keep her journalistic distance … until the killer contacts her, telling her that her children could be next. Now Nell must match wits with a psychopath who taunts her, daring her and the police to catch him before he can kill again.

Chapter 1

A storm was coming, the rising wind a harbinger of the tempest.

Nell reached down to grab at the stray sheet of newspaper as it scuttled in front of her. The light newsprint and the gusty wind conspired against her, but no one else was around to watch her awkward lunge.

She finally nabbed it when the eddying wind blew it back against her calf. Newspaper in hand, she headed for the trash can located outside the door of the city hall complex.

Nell paused at the garbage can. How easily I throw away my name, she thought. The wayward sheet was the editorial page, her name at the top of the masthead. Naomi Nelligan McGraw, Editor-in-Chief. It had taken her months to notice the change. “Who did this?” she had asked Dolan, the business manager. “You do the job, you get the title,” was his laconic reply. He hadn’t answered her question and Nell knew he wouldn’t.

The Editor-in-Chief is dead, long live his widow, the new Editor-in-Chief. The bitter thought caught Nell off guard. It’s been almost six months, she admonished herself, I should be over it. But she admitted she didn’t know how to lose the anger and grief that still blindsided her. How do you get over it? Or do you just learn to accept that you never will? One drunken driver, and the man she had planned to share her life with was gone. Here she was, living his dream, to run the paper that his great-grandfather had founded. Raising their two children alone.

What memories the wind brings, Nell thought as she again looked at the crumpled paper in her hand. She threw it in the trash can and entered the building.

Nell had intended to go to her right for the covered walkway that led to the library, but a glance to her left down the hall in the direction of the Mayor’s office, changed her mind.

A group of men were coming in her direction. She waited.

“Hi, Buddy,” she said as they got nearer. “Going to indict anyone I should know about?”

Buddy Guy, the county DA was an astute enough politician to know that Nell’s seemingly bantering question was really a reporter’s query.

“Howdy, Nell,” Buddy drawled. “Always a pleasure to run into you.” He extended his hand in the perfect politician’s handshake.

Buddy Guy—she always wanted to ask him if that was his real name or if a focus group had chosen it for him—had been coming down the hall with Douglas Shaun, the Chief of Police, Clureman Hickson the Sheriff and Harold Reed, Buddy’s top prosecutor. Seeing the police chief and the sheriff together was enough to raise Nell’s reporter’s suspicion.

Sheriff Hickson was so close to the archetypal good ol’ boy that Nell had to constantly remind herself he had to be more than just a walking stereotype. He had a beer belly, some of it gained while on duty. The sheriff saw nothing wrong with having one with the boys. He had been sheriff for over twenty years, so ensconced that no one had run against him for at least the last ten. His balding head and slicked back gray hair was usually hidden under a battered cowboy hat. He had never gone beyond high school and believed in ‘old fashioned law enforcement’ whatever that was. Nell suspected it was more to cover his mistrust of new techniques and the upheaval of change.

He and Nell were always polite to each other, but it was apparent he didn’t think that women should be working at all, editor-in-chief of his hometown newspaper was a change he’d clearly hoped to avoid in his lifetime.

Douglas Shaun, the police chief, was in many ways, his opposite. He was new in Pelican Bay, only four months on the job and he was younger, in shape, and taller than the tall sheriff, indeed most men. His hair was a curly sandy brown and he had a chiseled chin that wouldn’t look out of place on a movie star. His face had just enough lines and his hair enough gray to add maturity to his strong masculine handsomeness that many women found appealing. Nell didn’t consider herself one of them, Thom had had a boyish bookishness about him and that was what she found attractive. Shaun’s shirt and pants were always crisp and clean and his belt was loaded down with everything, gun, handcuffs, night stick. Chief Shaun didn’t treat her like a problem he hoped would go away, as Sheriff Hickson did. Shaun was an educated man and he was quite aware that having a good relationship with the editor of the paper could be very useful. He cultivated Nell, dropping by the office to brief her on things, even escorting her home one rainy night.

Nell was neither fooled nor flattered by it, but the police chief’s openness was a welcome change from the sheriff’s patronizing obtuseness.

There was in intense and ongoing rivalry between the two men, which made their appearance together unusual.

The Sheriff patrolled Tchula County and managed the county jail. In theory, he ceded jurisdiction to the town police at the city line. But there seemed to be good deal of misunderstanding about exactly where the town boundaries were, and who ruled what.

The latest scuffle was the recent drunken driving arrests made by Sheriff Hickson. Of course, he had consulted no one about setting up the roadblocks in town. “I got a right to clamp down on drunken driving where ever and when ever,” he had given as his quote the next day, “’Specially if no one else is doing it.”

Chief Shaun couldn’t publicly go after the Sheriff—he couldn’t risk being seen as soft of drunken driving. His official quote was, “We’re always glad of the help of our fellow law enforcement officers, especially when we’re busy with crimes against property and persons. It’s good to have the lesser problems like drinking taken care of.” Behind the scenes, a number of people, the Chief included, made grumbling noises about a set up to embarrass the Yacht Club and the people that went there.

Nell knew the Sheriff well enough to know that he had his own set of standards—he had set up his deputies the same distance away from both the Yacht Club and Ray’s Bar. He had stopped all the cars and treated everyone the same. It wasn’t his fault that the drive to the Yacht Club was around a leafy, curving roadway, making it impossible for anyone to know they were there. Ray’s Bar didn’t have any posh foliage blocking the view of the patrons, giving them more warning than the denizens of the Yacht Club.

More to the point, the Chief never turned down an invitation to one of the Yacht Club parties, whereas a goodly portion of the Sheriff’s corpulent stomach had probably come directly from the taps at Ray’s Bar.

Nell had to admit that, although she couldn’t disagree with the Chief’s assessment about the Sheriff’s wanting to embarrass the Yacht Club as much as catch drunken drivers, her sympathies were leaning toward the Sheriff. A drunken driver was a drunken driver—it didn’t matter how he got there, cheap beer or single malt Scotch.

Admittedly, some of her lack of sympathy for the Yacht Club’s embarrassment was caused by the Commodore of the Yacht Club Philip Yorst’s, clumsy attempt to cajole her to his view point.

“What’s the big deal?” he had said, having made a special trip to the newspaper office so Nell could get his side directly from him. “Some of our members are really sacrificing to pay those fines. We party and have a good time. A few drinks isn’t going to hurt anyone. You know that.”

Nell stared at him. She had never much liked him, but was always careful to not show it. Nell considered Yorst a social climber. He was known for having devised a uniform for the Commodore to wear, something ‘befitting the position’ as he said it. If he were going to pull the trigger on the starting pistol for the Yacht Club regattas, he obviously had to be properly attired to handle a weapon.

“No, I don’t know that. But I do know that I’m a widow, Mr. Yorst,” Nell had replied, her voice giving way to a steely anger she rarely showed, “because someone had a few drinks.” Nell had walked past him, out of her office, forcing him to foolishly stand there.

Nell tried to be a neutral reporter when caught between the rivalries, but her editorial on the ‘sacrifices’ of the ticketed drivers had been scathing.

More often than not, Nell found herself leaning towards, for lack of a better description, Chief Shaun’s/the Yacht Club’s side of things. She had more in common with them than she had with the Sheriff and the rough shrimpers who frequented Ray’s Bar. She had been a journalist long enough to know that perfect objectivity was a myth. She tried to be honest and fair and keep her sympathies well hidden. It usually meant that the liberals thought her a right wing dupe and the conservatives found her to be a godless Commie. Thom used to say, “Balance is pissing everybody off.”

She suspected she was going to come fairly close to that desired objective today. She doubted they were re-hashing the drunken driving skirmish, so she pressed them on the one other problem that might bring these men together, “This conclave wouldn’t have anything to do with the girl’s body that was washed ashore?” she asked.

“This ain’t a press conference,” Sheriff Hickson said.

“So, you’ve made no progress?” Nell queried.

“Well, I wouldn’t say that,” Buddy, the politician interjected.

“Was it murder?” Nell asked.

Buddy looked at his compatriots, as if not wanting to give an answer that might hurt his next election. Harold wouldn’t answer for his boss. Sheriff Hickson wasn’t going to answer a blunt question like that from a woman.

That left Chief Shaun. “We’re not sure. The body is badly decomposed. No clear indication, it’s possible the child drowned.”

“The fishes didn’t leave us much to go on,” Sheriff Hickson interjected. “You’re welcome to hop over to the morgue and take a look for yourself.”

“I’m very well aware of what sea water can do to human flesh.” Every sexist editor Nell ever worked for thought it was fun to send the new girl reporter off to look at bodies. “So, are you investigating this as a murder or not?”

“Soon as we got evidence it’s a murder, we’ll treat it like a murder,” the Sheriff retorted. “But unless someone confesses that’s not likely to happen anytime soon.”

“It’s a question of resources,” Chief Shaun said, giving the educated, slick version of the sheriff’s answer. “The local medical examiner can’t find anything to indicate it was a homicide. Most likely a tragic drowning. Can we afford to spend the kind of money it would take to chase this down?”

“Those people don’t seem to much care, why should we?” Sheriff Hickson added.

Buddy Guy rolled his eyes at the Sheriff’s remark, but didn’t directly contradict him. Harold Reed’s face remained impassive.

“Would the lack of resources apply if this were the child of a white, middle-class family instead of a poor, black one?” Nell pushed. She had been a better reporter than Thom. Sometimes she forgot the ways she balanced him out. She would ask the hard questions, push and probe until she got past the polite facade or carefully spun news releases.

“Hell,” Sheriff Hickson spat out, “The Dad’s got a dozen check kiting arrests and dear lovin’ Mom spent some time on the streets. You arguin’ to spend the taxpayers money on those kinds of people? I’m not a racist, lot of fine, upstanding black folk in this community, but these ain’t them.”

“Is the arrest report public record or can I quote you?” Nell asked him.

The Sheriff didn’t answer, and to make clear that that was all he had to say, he turned on his heel and left the building.

“It’s a tough call, Nell,” Buddy said, trying to undo the damage. “Oh, hell, Harold, you explain it, I got a meeting to get to.” Buddy did a much more decorous exit than the Sheriff. He clearly was avoiding the possibility that a quote from him about not doing an investigation would end up in the paper. Harold was on his own. If he said something that reflected badly on his boss, Buddy could deny it.

“We investigate all cases thoroughly,” Chief Shaun said. “It’s the results of the evidence, not the class or color of the person.” Clearly a quote designed for attribution. With that, he slapped his braided cap on his head and also left the building.

All those familiar with the inner workings of the Tchula County Courthouse knew that Buddy Guy was a very good politician and a not very good lawyer. His enviable record was the result of the man standing before Nell. She knew Harold only in a professional role. As always, he was impeccably dressed, a conservative charcoal gray suit with a sedate burgundy tie.

Camouflage or armor, Nell wondered. Or both?

“Don’t worry,” Nell said, “I won’t quote you on anything that will have Buddy worried about losing a few votes.”

Harold gave her a slight smile. “I wish we could go after justice, no matter what it takes. I wish we weren’t bound by rules and money and always weighing—what will it cost? Can we prove it? But, I’m sure you’ve covered enough cases to know how fragile the search for justice can be.”

“I know, we settle for the rules of law and hope that they come close.”

“We investigate and what do we find? An imperfect family, but nothing to indicate that either the mother or father are the kind of monsters who would kill their own daughter. As Sheriff Hickson so bluntly pointed out, we’ve got a suspicious body, but no evidence proving murder or abuse. We could make some phone calls, ship her to New Orleans or maybe even Atlanta and get a second opinion. And probably end up exactly where we are now. A girl dead and we don’t know how or why. Some deaths you have to let God take care of,” he finished with a sad smile.

“How do you stand it?” Nell suddenly asked, a question that pushed past the polite professional roles they had always presented to each other. “Hickson’s ‘I’m not a racist’ racism? That a slick, good old boy like Buddy gets elected, but . . . .”

“But I never will?” he finished for her. “Not while Tchula County is sixty-four percent white? Twenty years ago Buddy would never have hired me, no matter how many cases I won. It’s progress.”

“Is it enough?”

“No,” Harold answered quickly, a hint of the carefully controlled anger seeping out. “No, of course it’s not enough. It probably won’t be enough in our lifetimes. I teach my children what the word nigger means. They will probably teach their children.”

Nell suddenly felt the hot flash of a parent, at not just having to explain to your child that the world is an unfair place, but at knowing your child will inevitably run into a brutal wall of hatred. “What a horrid thing for a child to understand!”

“But they will run into it,” he said softly. “We have to prepare them.”

Nell thought of all the things she scrambled to keep her children safe from, and worried about—from something resembling good nutrition, to wondering if she should be talking to Lizzie about condoms and HIV. Maybe even Josh. It was such a balancing act. What would it be like to add the burden of racial hatred to the life of a young child? “How do you teach them to stand it?” she asked him.

For a moment, Harold was silent. Nell wondered if he was weighing his words, looking for the careful ones that wouldn’t sound too angry or strident to a white person.

“I tell them that it’s possible every day of their life, they will run into injustice, some slight, some moment when they will wonder, would I be treated this way if I weren’t black. They can fight every single battle and be angry every single day. And live an angry life. Or they can learn to pick the few important ones and let the rest go.”

“A hard lesson to learn. Thank you for answering my impertinent question,” Nell said.

“Most white people don’t thank black folks for being up front,” he said with a wry smile.

“You were honest. I’m a journalist, I like getting at least one honest answer a day.” Nell returned his wry smile. Then she became a reporter again and said, “I’d like to follow up on the girl’s death.”

“Why? Will it do any good?” Harold Reed asked, but it was an honest question, not a challenge.

“If she was murdered, it might remind the killer that murder has no statute of limitations, at least give him a few more sleepless nights. Maybe a story in the paper will jog someone’s memory. And if it was a senseless drowning, it might remind a few parents to watch over their children.”

“And maybe the killer will be so overcome with remorse at seeing it in the paper, he’ll confess,” Harold said with a small, sad smile. “But you’re right, we shouldn’t forget our dead so easily. Best person to talk to is her grandmother, she was more or less raising Tasha. Ella Jackson, on Rail Street. Should be in the phone book.”

“Thanks, Harold,” Nell said. There were rules—often overlooked—about giving out information. Letting her look up the phone number kept them just barely inside the lines. But Nell knew Harold Reed wouldn’t have given her the tip if he didn’t think she’d do the right kind of story. She took it as a compliment.

“Time to get back to the piled high desk.”

“Please call me if there are any further developments,” Nell asked.

“Of course. I’ll even call you and let you know if nothing can be done. Just don’t quote me on it.”

Nell gave him a nod to indicate she’d honor his request. He did have to work for Buddy Guy, after all.

As soon as Harold had disappeared through the outer door, Nell pulled a small notebook from her purse and jotted down the gist of the encounter. She wouldn’t take a story directly from this hallway meeting, although it was tempting to splash some of Sheriff Hickson’s quotes across the front page, but the notes could be useful.

She was glad that she had been able to get at least a little bit beyond Harold’s careful mask. On a personal level, she knew he was a very intelligent man and his honesty was a compliment to her. On a professional level, it had formed a connection with a man who could give her better information and stories than anyone else in the D.A.’s office. Nell had a feeling that they could use each other, in the good sense of the word. Harold would have information she wanted and she had the power to get out stories that would otherwise be shuffled away.

Nell put the notebook back in her purse. Not a bad twenty minutes, she thought. She headed for the library.

As she pulled open the door leading into the library wing, she heard someone say, “Rayburn, look out for that lady.”

But Rayburn, newly six, wasn’t looking for a woman standing on the far side of the door he was using to slingshot around. He caromed into Nell, then spun away with aplomb, as if running into the legs of strange women was an everyday occurrence.

“Rayburn, you slow down, now,” his mother called after him, as he sped up through the library doors.

His mother apologized to Nell, “Sorry, ‘bout that. He’s just got so much energy,” in a way that told Nell that she was proud of her energetic boy.

Velma Gautier, Nell knew her name—the births and deaths of Pelican Bay were with her every day. Velma had had Rayburn when she was forty-two, the last of eight children and five years younger than the previous sibling. Velma’s voice held a touch of pride that an old lady like her could produce such a robust young son. Six of her other children were girls and the only other son had very bad asthma.

“It’s okay,” Nell said as she diverted her thoughts from the tragedy of a young girl who death had only questions and no answers. “He’s certainly an active young man.”

“Oh, yes, that he is. Keeps me hoppin’,” Velma answered.

Velma Gautier looked more like Rayburn’s grandmother than mother. Nell found herself wondering how she would write Velma’s story. It was something she often did with people, made them into newspaper stories. Sometimes she wondered if it was a way to control and encapsulate people, or it was just habit and the way her brain worked and not something she should worry about.

Wind and water had aged Velma and roughened her. She worked at the seafood store located at the mouth of the harbor, sorting and peeling the shrimp and crabs that the boats brought to the docks. Her husband, Ray—was it just Ray or had his son been named for him?—used to be a shrimper until an accident had taken off most of his left arm. Then he had rented the unused cement block building on the harbor’s edge and turned it into Ray’s Bar, the name in hot pink neon and beer signs in all four windows.

Ray and his bar had occasionally demanded Nell’s attention because at least once a year, the Pelican Bay Yacht Club would try to get Ray’s Bar zoned out of existence. They had come so close to getting the unused building torn down that they felt cheated when Ray had revived it and turned it into a bar. The Yacht Club, located on the other side of the harbor, didn’t like having one of its vistas contain pink neon bar signs and advertisements for beers like Miller, Dixie and Bud.

Last month, Philip Yorst, the current commodore, had written a letter to the editor complaining about drunken drivers in the harbor vicinity. That was the match to the drunken driver fire. Sheriff Clureman Hickson had set up spot checks for the next Saturday night. His men (and one woman—things were progressing a bit) arrested one drunken driver on Ray’s side of the harbor and ten coming out of a Yacht Club party.

The Town Alderman (no women there, yet) had mouthed the usual platitudes and as usual, when the votes were taken, no one wanted to go on record for rezoning Ray’s Bar, with its one-armed father of eight, out of existence, while allowing the Yacht Club to continue its well lubricated events.

Velma often worked in the bar after her day in the seafood place (it had a name, but everyone referred to it as the seafood place and that was how Nell thought of it). The older kids were left to take care of the younger ones.

It was a life that had produced the woman in front of Nell, Velma’s face etched in lines, her hair course and gray, the body lumpy and sagging.

“How’s Miz Thomas doing? Haven’t seen her in the shop of late,” Velma asked Nell.

Miz Thomas was Mrs. Thomas Upton McGraw, Sr., Thom’s mother.

“She’s fine,” Nell replied, “I talked to her just yesterday.”

“Good to hear. Sometimes you just wonder when you don’t see people around. Well, let me go find Rayburn ‘fore he runs all over.”

Nell held the door for Velma to enter the library, then stopped at the water fountain to avoid tagging silently behind the slower woman.

Thom had been the charmer, the one who could move from the Yacht Club to Ray’s Bar with a patter of small talk and jokes that opened people up. He sometimes had referred to himself as the beauty and Nell the brains of the operation.

Thom would have been bantering with Velma Gautier, offering to carry her stack of books, asking about her other kids and Ray and what had just gotten off the boat, was the red snapper or the speckled trout good today.

Nell could be genial, she had learned a lot from Thom during their marriage—but never with the ease that he had.

Like now, she had thought of the things to say to Velma, but only when it was too late, with Velma already at the library counter, checking her books back in.

Nell joined her, putting her books down on the counter just as a crack of thunder boomed overhead.

Marion, the librarian, flashed a quick smile at her, as she checked in Velma’s stack of books.

“Wow! Dinosaurs,” came Rayburn’s voice from the children’s corner.

“Rayburn, you be quiet,” his mother shushed him.

“It’s okay, let him enjoy his dinosaurs,” Marian said. “Just us in the library right now.”

Nell glanced at the stack of books Velma was returning. Several children’s books clearly for Rayburn, quite a few romances—Nell wonder if Velma was a romance reader, then remembered the romances in her to-be-returned pile. She just had one teen-age daughter and Velma had several.

Someone looking at her stack of books, might have a few questions about the reading taste of Naomi Nelligan McGraw, Editor-in-Chief of the Pelican Bay Crier. At least Marion the librarian knew the truth. She knew which romances and make-up books Lizzie had picked out, the animal stories and bicycling books for Josh, and which books Nell chose.

Nell had always liked Marion, sensed that they might become friends some day. So far their meetings had been only during Nell’s weekly library trips and a few social events here and there. And Thom’s funeral. Marion had been there.

Nell watched her as she checked in Velma’s books. Marion was an attractive woman and Nell wondered, why, at thirty-four, she had never married. Thom’s mother and Marion’s mother were close friends and Nell had occasionally heard their discussing and comparing their children. Peyton Nash, Marion’s father had died a while ago and Nell knew that Erma, her mother, was in frail health.

Attractive in a bookish way, Nell had to admit, her dark hair in a short practical cut, her glasses were a rounded tortoise shell, the kind that branded her as a serious book reader. She was tall. Nell, at five-seven, had to look up to her. Nell wondered if she remained in Pelican Bay to care for her mother. Her two brothers had moved on, one in the military and the other into computers out in California. Marion, the single daughter, had returned. Nell had gathered all this information from Mrs. Thomas, Sr., not from Marion herself, and it suffered from Mrs. Thomas’ way of looking at the world.

“C’mon, Rayburn, get your books ‘fore the rain starts,” Velma called to him.

He spun up to the desk with a handful of books one of them hanging open showing a picture of ‘our friend, the policeman.’ Running seemed to be his preferred method of locomotion.

Nell left her returned books on the countertop and wandered over to the New Books shelf. Nothing really caught her interest, but she hadn’t been planning on taking out any books, today’s errand was really just to avoid crossing the fine deadline. She’d bring Josh and Lizzie to get new books. She’d have leisure then to look for herself while Josh searched for books about whales or bicycling, his two current obsessions. Lizzie could spent ten minutes looking at one book, measuring it in ways that Nell couldn’t fathom, before deciding whether it was worthy to be carried home or not.

The purpose of her dawdling, Nell admitted, wasn’t the books, but to take the first tentative steps past acquaintanceship to friendship. The immobility of grief was lifting and loneliness was seeping in. When Velma and the boisterous Rayburn left and there was a quiet moment, Nell would ask Marion to go for coffee sometime.

She’d had one of those nights last night, lonely and discontented, far enough past the numbness to know how empty the bed was. The sleepless night had firmed up her resolve to cut away some of the loneliness.

For Thom, it would be easy, he’d just plop the books on the counter and say, “How about coffee? I’d love to talk about books with you.”

But Nell was too deliberate, too cautious just to brazen into friendship. Sometimes she wondered if she was mythologizing Thom, erasing his faults, giving him a perfection that real life would never challenge.

With a shake of her head, Nell decided, I don’t need to do that, his mother does it well enough for both of us. Her relationship with Thom’s mother had never been easy, but now there was a subtle, unspoken war between them over . . . over what? Thom’s memory? What he might have done, might have said? His soul?

“Do you think Thom would really agree with that editorial,” his mother would politely ask. Or, “Thom’s father never would have done that. I suppose it’s something he learned in journalism school.” Nell heard the unspoken, “From journalism school and you, because he certainly didn’t learn it from us.”

Clearly I need someone to talk to, Nell thought as she turned from the book shelves.

“Any new books you’d recommend?” Nell asked Marion.

“Plenty I’d recommend. But you’ll have to go to a bookstore for them. The first thing to go in the city budget is the library.”

“If you’ve got Dickens and Shakespeare, what more do you need, right?”

“As if our city councilmen know who Dickens and Master Will are. No, they like the latest bestsellers, so that’s the direction my meager funds go. Do I buy the most interesting books or the books that more people will read?”

“It’s a book eat book world,” Nell replied, getting a smile from Marion. “How about going out for coffee sometime? Lizzie and Josh have at least a decade to go before we can talk about the same books.”

“Coffee?” Marion repeated slowly, possibly with hesitation, but Nell wasn’t sure. Maybe I’m seeing more than is really here, Nell suddenly thought, but then Marion continued, “That would be nice—if we can work it into our hectic schedules.”

“Mine’s kids and the paper. How about Friday? That’s best for me, the paper’s out and I’d just as soon not be near a phone to hear about things from misspelled names to our editorial page being run by leftists to the left of Marxist-atheistic Communists.”

“Friday, let me think . . . ,” Marion again slowly replied.

“Or you can get back to me, if you like,” Nell added, still sensing some hesitation on Marion’s part. She didn’t know Marion well enough to know whether this was just the way she did things, or if she had some reservations about seeing Nell outside their limited library meetings.

“Friday doesn’t work. How about Saturday?. I was just trying to remember Mama’s schedule,” Marion said. “I have to be here part of the day. How about mid-afternoon? I can text you when I’m about to leave.”

“Sounds good to me,” Nell said, giving Marion her cell phone number. The work one, Nell had eschewed having to juggle two cell phones, so the official Crier one did double duty.

Just then a gaggle of school children rushed in through the door. They surrounded Marion and the main desk and bombarded her with questions about the settling of this part of the Gulf Coast. It had the unmistakable earmarks of research paper due tomorrow.

Nell couldn’t see herself being heard above their cacophony. She gave Marion a smile and a wave and headed out the library door.

As she opened the door to leave, the rain came down, windy sheets that made an umbrella useless.

The storm had come.

Copyright © 2017 R. Jean Reid.

To learn more or order a copy, visit:

opens in a new window![]() opens in a new window

opens in a new window![]()

R. Jean Reid lives and works in New Orleans. She grew up on the Mississippi Gulf coast. As J.M. Redmann, she is the author of multi-Lambda Award-winning Micky Knight Mystery series, including The Intersection of Law and Desire, Death of a Dying Man and Ill Will. Her day job is in public health as the director of prevention at NO/AIDS Task Force.

So far, it has reeled me in! Want to find out what is next. I like the range of characters.

This will be on my must read list. It will be interesting to see the different ways the police and sheriff approach the child’s death.

Looks like a great read!