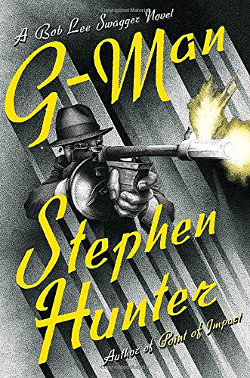

G-Man by Stephen Hunter is the latest installment in the bestselling Bob Lee Swagger series, which finds Bob uncovering his family’s secret tommy gun war with 1930s gangsters like John Dillinger and Baby Face Nelson (available May 16, 2017).

1934. The depths of the Depression were marked by an epidemic of bank robberies and the swashbuckling, Tommy-gun-toting outlaws who became household names. John Dillinger. Bonnie and Clyde. Pretty Boy Floyd. Hunting them down was the new U.S. Division of Investigation—soon to become the FBI—which was determined to nab the most dangerous gangster this country has ever produced, a man so violent he scared Al Capone and was booted from the Chicago Mob—Lester Gillis, better known as Baby Face Nelson. To stop him, the Bureau recruited the most talented gunman of the time—Charles Swagger, World War I hero and sheriff of Polk County, Arkansas.

Eighty years later, Charles’s grandson Bob Lee Swagger has finally decided to sell the family homestead, but when the developers begin to tear down the house, they uncover a strongbox hidden in the foundation. Enclosed is an array of memorabilia dating back to 1934—a much-corroded federal lawman’s badge, a .45 automatic preserved in cosmoline, a mysterious gun part, and a cryptic diagram—all belonging to Charles Swagger. Fascinated and puzzled by these newly discovered artifacts, Bob is determined to find out what happened to his grandfather, who died before Bob was born, and why his own father, whom he worshipped, never spoke of Charles. But as he investigates further, Bob learns that someone is following him, that someone is sharing his obsession with finding out what Charles Swagger really left behind.

PRELUDE

EAST OF BLUE EYE, ARKANSAS

The present

The blades of the graders contoured the land to spec. They rounded hills, felled and flattened woods, scoured underbrush, crushed rocks, filled hollows, collapsed ravines. Nothing but raw earth remained. What had been complex became plain, according to the latest large-project construction principles. Streets had been staked out, while sewers and wiring and cable were planted in furrows. Then the houses would spring up, rows of them, all alike, but soon to be differentiated by their new owners. It was progress or, at least, development—it was growth, it was capitalism, it was hope. It couldn’t be stopped, so mourning was pointless.

This land had sustained one family for more than two centuries, first claimed in the late 1780s by a quiet couple from over the mountains, where the war was just finishing. They gave no account of themselves. They and theirs stayed for seven generations, and for that whole time they were steady, solid; they went to church, they gave to charity, they did their share in emergency or crisis. But more, it turned out they were a family of heroes. Their boys learned to shoot; they learned the hunter’s patience, his stoicism, his courage, his mercy, his honor. They had a gift for the firearm, and more than a few of them took that gift off to war. Some made it back, some didn’t. Some became officers of the law, for in those days that too called for the shooter’s talent. They shot for blood many a time, and, again, some made it back and some didn’t.

They were all gone now. The last of them had sold off the place for a substantial amount and fled, not wanting to see what was done to his home-stead and the homestead of his ancestors.

Now the contouring was all but finished. Only the old house remained, atop a hillock that dominated the spread, a comfortable, rambling joint that had been added to over the decades until it practically made no sense at all. The hill was too much for the graders and so the company brought in a big Cat excavator, the 326F L model, a machine classified medium by weight, and set it loose, under the guidance of a professional genius named Ralph.

From afar, it looked like some kind of Jurassic ritual. A yellow Tyrannosaurus rex had downed a Bronto or a Stegosaurus and now fed on soft underbelly. The knuckle boom of Ralph’s big Cat pierced and ripped and tore, its bucket armed with side cutters and teeth, taking down walls and floors swiftly, in a single day reducing what had been a large house to a large pile of rubble. The next day, using the bucket as an artist would a brush, Ralph cleared the shattered remnants of two centuries’ worth of history, loading them into the trucks, which hauled them off to the landfill. Finally, on the third day, only the foundation remained, and he directed the bucket to continue its feast of destruction, smashing the stones into smaller chunks, then scooping them up for disposal. It was all going according to plan—until it wasn’t.

The managers saw him stop, pop the big machine out of gear, turn off its hydraulics, then leap from the yellow house, dash along the tread and swing down off the boom, pass under the knuckle, and reach the bucket, which was frozen in place on a particularly large chunk of foundation that would not shatter according to plan.

They approached and swiftly became an inspection committee. “Something wrong, Ralph?”

“You didn’t bust a pump or lose a piston?” “Did you spring a hydraulic leak there, Ralph?”

Of course all this really meant but one thing: how much is this going to cost us?

But Ralph was on his knees, studying on the joinery between the bucket’s teeth—those hard T. rex fangs—and earth.

“I felt something,” he said. “You know, you get so you can read the vibrations. It wasn’t stone, dirt, pipe—nothing like that.”

He poked, prodded, messed around with a spade. “What’d it feel like?” he was asked.

“Some kind of metal. I don’t know, a sheet or a—”

He stopped, spotting something, leapt forward, examined more closely, inserted the shovel’s blade, dug, pried, cleared, sought leverage, and finally, with a spray of dirt like an explosion, exposed something from the Great Beneath.

“Jesus,” he said, now pulling the treasure free, “it’s a strongbox of some kind.”

It was, looking like the sort of thing carried by Wells Fargo and subject to larceny by men in dusters and hats, with bandannas across their faces and Winchesters in their hands.

The committee gathered around. Curiosity now overcame their need, if only for a bit, to stay on schedule.

“Maybe it’s full of gold,” somebody remarked.

Ralph, whose genius was practical, not speculative, smacked at the pad-lock a few times with his spade, expertly driving the corner tip of its blade under the locking hasp, and the hasp’s old metal couldn’t bear the spike in pressure and broke open on the third blow.

The committee gathered closer as he tossed the busted lock away and pulled the lid back on the strongbox’s rusted hinges.

The contents were initially disappointing. A number of objects wrapped tightly in heavy canvas, loosely secured by disintegrating tape, their outlines muffled by the heavy swaddling. Ralph popped a Kershaw knife from the pocket of his jeans, where it had been clipped, cut the tape, and used the point of the blade to push through the mass of canvas. It gave way to an oily cloth wrapping, under which the thing, shed of its canvas raiments, assumed a familiar shape. At last, he got this final oily wrapping away from it and held it out, gleaming in the sun, for all to see.

“It’s a damned pistol,” he proclaimed.

“It’s an old .45 automatic,” someone who knew said. “Old?” someone else said. “Hell, it looks brand-new!”

They were otherwise stunned into silence. Finally someone said, “Man, I bet that bad boy has a story to tell.”

Copyright © 2017 Stephen Hunter.

To learn more or order a copy, visit:

opens in a new window![]() opens in a new window

opens in a new window![]()

Stephen Hunter is the author of more than twenty novels. The retired chief film critic for The Washington Post, where he won the 2003 Pulitzer Prize for Distinguished Criticism, he has also published two collections of film criticism and a nonfiction work, American Gunfight. His novel, Point of Impact, was adapted for film as Shooter, starring Mark Wahlberg. He lives in Baltimore, Maryland.