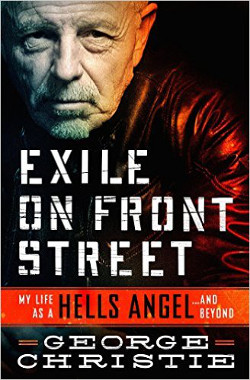

Exile on Front Street by George Christie is the true crime memoir of an outlaw biker and former member of the infamous Hells Angels (Available September 20, 2013).

Exile on Front Street by George Christie is the true crime memoir of an outlaw biker and former member of the infamous Hells Angels (Available September 20, 2013).

After forty years in the Hells Angels, George Christie was ready to retire. As president of the high-profile Ventura charter of the club, he had been the yin to Sonny Barger’s yang. Barger was the reckless figurehead and de facto world leader of the Hells Angels. Christie was the negotiator, the spokesman, the thinker, the guy who smoothed things out. He was the one who carried the Olympic torch and counted movie stars, artists, rock musicians, and police chief captains among his friends.

But leaving the Hells Angels isn’t easy, and within two weeks of retirement, he was told he was “out bad”—blackballed by his fellow Angels, prohibited from wearing the club patch, and even told he should remove his Death Head tattoo.

Now Christie sets out to tell his story. Exile on Front Street is the tale of how a former Marine gave up a comfortable job with the Department of Defense and swore allegiance to the Hells Angels. In this revealing, hard-hitting memoir, he recounts his life as an outlaw biker with the world’s most infamous motorcycle club.

1

I was born in Ventura, California, but I was raised in Sparta.

My grandparents on both sides were Greek immigrants. In the fifties, Ventura had a tight-knit Greek community that was suspicious of outsiders. There was Us and there was Them. Cops, courts, politicians, were Them. Anybody who wasn’t Greek was Them. We took care of ourselves. Greeks owned a lot of the local businesses. Restaurants, machine shops, five-and-dimes. My grandfather was a cobbler. The Greek attitude was “Who needs them?” You have a problem? Take it to AHEPA (American Hellenic Educational Progressive Association) or Daughters of Penelope. As I would later discover, the outlaw culture had the same outsider perspective. That was one of the things that ultimately attracted me to the outlaw lifestyle. The unwritten rules were familiar.

But to a kid, the Us-versus-Them thing was confusing. My grandparents on both sides had changed their names. Vlassopoulos became Blacy. Chrispikos became Christie. If it’s Us, why change your name unless you were ashamed? I also knew early on that people in town looked down their noses at Greeks. We weren’t respectable society.

I was overweight, something else that made me an outcast. Food is love in a Greek house, and there was lots of love in our home. My dad was a fantastic cook, and I was pudgy until I started high school. Being Greek and heavy made me a target, though I was only physically bullied once. It was the first time I used my fists and my temper to solve a problem. But the experience lit a white-hot anger in me that would eventually die down, but never go out. To this day I despise bullies. Of course, you don’t need to be bullied to be an outcast. Kids made fun of me and refused to have anything to do with me.

That was a big part of why I hated school. It didn’t help that anytime I read more than a couple sentences letters would jump around and change shape. Numbers would become letters or vice versa. A b would become a d. It was frustrating as hell. It would be a long time before anybody put the word dyslexic to it. At the time, I was just written off as lazy. Outside of school, I spent most of my time with my family. My mom and dad were fun and devoted parents. I always knew that I was loved unconditionally. Laughter was the sound track of the Christie house. My mom loved a good laugh, a joke, and the holidays. That’s how we came to have a talking Christmas tree.

When I was six, my mom told me our Christmas tree would talk if my cousins and I were good. So we’d sit politely around the tree, draped in jewel-colored lights and glittering tinsel, and do our best to behave. The pine smell filling the living room, the tree would come to life: “How are you girls and boys tonight?” We’d stare in wonder. Then it would say, “I see little Jimmy there. Are you still picking on your sister?” Jimmy’s eyes would get huge and he’d shake his head no. If I’d been a smarter six-year-old, I might have thought it a little weird that our Christmas tree had a Spanish accent. Up in the rafters talking down through a disconnected heating vent was Chubby, the Mexican woman who lived next door. But that tree kept a whole neighborhood full of kids polite and well behaved throughout the holidays.

Although my mother, father, and I lived in Camarillo, I spent most of my time in Ventura at my grandparents’ house. Pappoús Blacy owned a small shoe repair shop right behind the tiny two-bedroom clapboard house he shared with Yiayiá. Pappoús was lord of the clan, feared as much as loved. His nickname was the Governor. He had no formal education to speak of, but he was one of the wisest men I’ve ever known. He was a short, barrel-chested Greek, with a confident, imposing presence. He wore dark-framed glasses and a brown fedora, and he was built solid, as if he were rooted to the earth and nothing was going to move him if he didn’t want to move. Yiayiá was the flip side of the coin, just as strong as Pappoús, but sweet, gentle, loving, and unbelievably kind.

They made Ventura special for me, but the town itself was a kid’s paradise. If my cousins and I weren’t begging quarters off Yiayiá (Pappoús had cut us off because our tab with him got too large) to buy cherry Cokes at the corner drugstore soda fountain, we’d head down to Ventura’s long wooden pier to fish off the side. Nobody had money, but there was still plenty to do. My happiest childhood memories involved that combination of Ventura and family.

My dad eventually bought a diner, the Frontier Café, where I worked on and off until I graduated high school. Sometimes, after a morning of surf fishing, my mom, dad, and I would scout out other family-run restaurants to see what they were doing with their menus and what might work in our restaurant. We called ourselves “the three Gs”—George, Georgia, and Georgie. One Sunday we had lunch at a local Italian place, an old-school trattoria with checkered tablecloths and empty, straw-wrapped, potbellied Chianti bottles used as candleholders, draped in a hundred coats of red wax. The owner came and sat with us, talking in broken English about how his business was doing. When we left, he walked out with us. As we were saying our good-byes, a low rumble grew into a thunderous roar that shattered the quiet afternoon. A biker pulled up at the stoplight about twenty feet from us. It was the first time I had seen an outlaw up close. It was 1955. In school, most of us had buzz cuts and wore pressed trousers. This guy wore a denim jacket frayed where the sleeves had been cut off, and blue-black jeans crusted with road grease and dirt. His Ray-Bans were pushed up high on his forehead, holding back a wild mane of black hair. He seemed like a magician, controlling everything around him. People on the sidewalks were frozen in the moment. As he idled, the pipes quieted, and I could hear the distinctive rattle of the clutch basket ringing out. He just sat there on that hand-built Harley bobber. Then, in perfect sequence, he lowered his sunglasses with his left hand, cracked the throttle with his right, pushed the suicide clutch with his foot, and jammed the jockey shifter into first. He reached up over his shoulders to grab the handles of his “ape hanger” bars, gave it the gas, and shot across the intersection. It seemed like he disappeared in a blink, leaving just echoes and a memory etched in my mind.

The restaurant owner broke into a tirade. “Look at him, worthless. Goddamn animal.” The man spat into the street and looked down at me. “That’s your America.”

I thought, “You bet it is.” It was hands down the most amazing thing I’d ever seen. It wasn’t just a kid’s fascination with something shiny and loud. Deep down I realized that this guy wasn’t playing by anybody else’s rules. He was doing his own thing and saying to hell with anyone who didn’t like it. Nobody was going to bully him, and he didn’t need anyone’s approval. He was in control. To an unpopular, chubby, little Greek kid, that seemed like a magical idea.

As the years went by, society kept pushing me in the direction of the outlaw, even as my parents and grandparents kept me grounded. Surfing became a part of that push-pull. Living so close to the beach, I was inevitably drawn to the sport. My parents thought it would be a good, wholesome way for me to spend my time. We had moved to Camarillo from Anaheim right before I started junior high school partly because the Anaheim schools had a lot of juvenile delinquency. So my parents were keen on my being involved in something positive.

I bought my first board for $40, with a little financial help from my mom. It was a butt-ugly olive drab, but it felt like I’d latched onto something, an identity I could own. I started hanging out at the beach every day, picking up techniques and learning how real surfers behave.

Surfing changed everything. I loved the water anyway, and surfing wasn’t like other sports. You didn’t need a team or a lot of gear. It didn’t require special talent, size, or huge muscles. You just needed to practice. Nothing replaced time spent on the waves. I was also a natural from the start, and it felt so great to find something I was good at, something that I could claim as mine.

A waitress in my dad’s restaurant had a son who was an avid surfer. My dad asked her if her boy would take me out and give me some pointers. She was all for it. But her son, John Schoemer, wasn’t as thrilled. He was seventeen to my fourteen, and I’m sure his idea of surfing didn’t involve dragging some kid along. But among surfers—like among bikers—how you handle yourself is everything. Perform, honor the code, and you earn acceptance. Once he and his friends found out that I could hold my own on the swells and respected the way things were done on the waves and on the beach, I became one of them. It was a first for me, being a part of a group outside of the Greek community. The other guys were older and some of the roughest characters in Oxnard. The leader was a Samoan named Doodie Juarez, 220 pounds of pure muscle. He was an artist on a surfboard and a legendary fighter. After a day of surfing, he and his friends loved to drive down to Point Mugu and get into fights with the Seabees from the Point Mugu Naval Air Station. Long days spent shredding waves were followed by long nights drinking dollar jugs of wine around bonfires on the beach.

Surfing was my introduction into an outlaw brotherhood. The average person didn’t know real surfing culture. It wasn’t the clean-cut, corny world of Beach Boys songs and Annette Funicello movies. Surfers were athletes, but they weren’t jocks. They were outlaws. Like any outlaw group, they had a pecking order, with the toughest dog at the front of the pack. You had to regularly prove yourself. We had turf. Surfing a new beach without knowing the regulars meant somebody was going to dump you in the waves and throw you a beating on the beach when you came in. Just as a Harley and a leather jacket don’t make you an outlaw club member, owning a five-foot piece of fiberglass and foam won’t make you a surfer. You have to know and respect the code.

Being part of that group didn’t mean leaving my parents behind. They stayed involved with whatever I was interested in, and that included surfing. My dad read my issues of Surfer and knew almost as much as I did. So he understood when I told him I had to have a Dewey Weber board.

My first board had become an embarrassment and the butt of jokes. Dewey Weber was a legendary surfer who had started making a line of boards that defined surfer cool. A surf shop in Hermosa Beach sold the boards. My dad agreed to drive me there and let me pick one out. I was just about to turn fifteen, and—much as I loved him—I did not want to be seen with my old man. I made him promise to stay in the car while I went inside. It was the hippest surf shop I’d ever been in, with Technicolor boards lined up along the walls and a fire pit right in the center. Walking through the door, I was stunned to find Dewey Weber and Harold “Iggy” Ige warming themselves around the pit, still wet from the morning waves. These were my idols. They were rebels, gods. I was trying to comprehend finding myself in the same surf shop as these two when I heard a voice boom out from behind me.

“Hey, Dewey! You think we can find this gremmie a board?”

True to form, my father’s promise was a fake-out. He had waited about ten seconds and then followed me into the shop. Gremmie is surfer slang for a total novice, someone who wouldn’t know one end of a surfboard from the other. My dad knew this. He also knew who Dewey Weber and Harold Ige were.

“Iggy! How are those waves breaking?”

I tried to pull my head down into my body like a turtle. But as luck would have it, although Dewey Weber was considered a pure surfing outlaw with his wild shoulder-length hair and scraggly beard, he was also a class act. He came over and talked to us like we were old friends. He asked me about my stance and what kind of board I wanted. I got my Dewey Weber board, I met the man himself, and I went to sleep that night one very happy kid.

Thanks to a summer spent surfing every day, I started high school in great shape. Hanging out with the Oxnard guys also gave me a “fuck everybody” attitude. I promised myself that I would never again care about what people thought of me. That attitude played well in high school. People wanted to be my friend. Kids asked me to hang out. They wanted to talk to me in class and invite me to parties. Anyone might have thought it was a big break.

It just pissed me off.

Those were the same kids who had made fun of me when I was that overweight Greek kid in the back of the classroom. I hadn’t changed. I was still me. I was still Greek. My parents still loved me. But suddenly, because I was thinner and had an attitude, I was cool? It was hypocritical bullshit, and it made me unreasonably angry.

I still struggled with schoolwork and I got to know the principal, Mr. Killingsworth, all too well. He was a former wrestling coach, built like a tank with a big round head, jowls, and a crew cut. He looked just like a bulldog. The look matched his attitude. Without meaning to, he taught me lessons that had nothing to do with math or history. The biggest was to never trust authority figures. I learned that one after I took a standardized intelligence test with the whole school. It was easier than most tests because it was mostly diagrams and puzzles, or simple multiple-choice questions. No big sections of text to give me a headache, and no writing. I didn’t know what the point was, but it was a nice break from the dull routine of regular classes. A couple days later, I got called into the principal’s office. I walked in to find my parents sitting in two chairs with an empty stiff wooden chair right between them. I was in trouble; I just didn’t know why. Mr. Killingsworth looked angry.

“Sit down, George.”

I sat between my parents, facing him head-on.

“Do you know why you’re here?”

“No.”

“We want to know where you got the answers to the test.”

“What do you mean?”

“You cheated on the test. I want to know where you got the answers.”

“I didn’t cheat.”

I looked at my parents, and for the first time in my life, they weren’t backing me up.

“Then explain to me how you managed to score at the top of the test, but your grades are all C’s and D’s? Can you explain that?”

No, I couldn’t. We went round and round. How did you cheat? I didn’t cheat. Of course you did, until my mom finally chimed in. “My son says he didn’t cheat, he didn’t cheat.”

Killingsworth gave up. No apology. To him, there wasn’t even the possibility that I wasn’t lying. Another of Them looking down his nose at me. It left a bad taste in my mouth, but I learned. People were going to make up their minds before they even had the facts, without giving me a chance. The truth didn’t matter. It wouldn’t change their opinions.

That was part of what made school like doing time. I felt most like myself when I was hanging out with other surfers. Friday nights we’d kill time in the lemon orchards, drinking beer and smoking. Then we would cruise the town looking for parties. Normal teenage stuff. I got to know the local cops, who made us empty many beers into the gutter. I never got into serious trouble. But my attitude, and who I hung out with, earned me a reputation.

That’s why my cousin Chrissie came to me for help. Her friend Cheryl Sanderson was having a problem with a senior at school. He was harassing Cheryl with aggressive sexual comments. He was just another bully. This guy had a crush on this pretty, petite, quiet redhead with her nice Dentyne smile, cute freckles, and pixie nose. But like any bully, the only way he could express his feelings was to intimidate her. Greek kids are taught to respect women. So after Cheryl told me some of the things he had said, I agreed to talk to him. I found him in the hall and we set up a meeting after school, in a far corner of the practice field. I wasn’t calling him out and I didn’t think we needed to fight. I just wanted to straighten the guy out with a little lecture. Kids gathered, though, expecting action.

“Look, man, you have to quit talking shit to her. It’s not cool. Keep it up and we’ll have a problem.”

He seemed to get the message. He wouldn’t look me in the eye, but he said, “Sure, no problem.”

As I turned to walk away, he sucker punched me in the head. I went ballistic. There’s no temper like a Greek temper. He was bigger than I was, but I spun him around and hit him hard enough to knock him down. I put my weight on his back, holding him facedown. I locked his arms behind him. It had rained recently, and there were big puddles everywhere. I pressed his face into about two inches of water. He struggled, but with me on top of him, he wasn’t going anywhere. The other kids freaked out. They thought I was going to drown him. After half a minute, I let him up. I left him with a warning that if he ever crossed paths with Cheryl or me again, he’d wind up swallowing a lot more than some muddy water.

Word spread. Cheryl thanked me for my help. It was the first bond between us, a hatred of bullies. I would ultimately discover that she had skeletons in her closet that made her desperate to maintain control over her life. It was an obsession for her, being in control. I hated feeling out of control myself, so I kind of got it. We became friends even though we didn’t travel in the same circles. I still hung out with surfers.

One of them, Vaughn Lammars, became one of my best friends. Vaughn picked up the nickname Birdie Bighead because he was skinny and had a big head. He wasn’t much of a surfer, but he was funny and social, and he knew everyone worth knowing and was a kick to be around. Bird was the first in our group to ride motorcycles and would introduce me to the outlaw culture.

Another friend, Danny Brucker, fanned those flames. Danny’s father owned a company that provided cars, motorcycles, and related props to the movie business. The family lived on a huge ranch in Somis, where I learned to ride motorcycles. Danny’s old man stored a football field’s worth of amazingly cool cars and bikes. The most famous were displayed in their museum, Movieworld Cars of the Stars. Danny drove a different set of wheels to school every day. One day it would be a 1942 coupe from some gangster movie. The next, he would pull up on a perfectly restored Indian Scout, with its Indian-head front fender and wide buckhorn handlebars. These beautiful customized rides were courtesy of Dick “Woogie” Woods. He was a mechanical genius and a customizing artist who worked for Danny’s father. Dick was also a founding member of the Question Marks, a Southern California outlaw motorcycle club.

In my junior year, I bought a brown 1953 Ford sedan and painted it taxicab yellow. Anyone who rode in it had to sign the white headliner. It was a hit with the girls, and I wound up dating several. That’s when I picked up that Cheryl was interested in me. She never missed a chance to ask about who I was dating or to tease me about my “girls.” Normally, someone like Cheryl would have seemed unattainable. She was one of Them. She came from an upscale WASP family with a big, beautiful house in the best part of East Oxnard. But once we started dating, the differences didn’t seem to matter. Eventually we started talking about the future. It was the norm in the midsixties. A lot of people got married right out of high school. It seemed natural that we were a couple and would stay a couple. But I was a kid. I wasn’t thinking about the future; graduation was as far down the road as I could see. Whatever my future held, it would have to wait. Our relationship would have to wait. There was a war on, and I was about to become a Marine.

Copyright © 2016 George Christie.

To learn more or order a copy, visit:

opens in a new window![]() opens in a new window

opens in a new window![]()

George Christie served as a Marine reservist and, after completing his service, became an electrician and communications troubleshooter for the Department of Defense. He prospected for the Hells Angels Motorcycle Club in 1975, becoming a full-patch member in 1976, eventually founding the Ventura charter and serving as its president for more than thirty years. He also served as the club’s international spokesman for more than two decades. He lives in Ojai, California.

“Exile On Front Street” is the most interesting book on the “Outlaw” culture of Motorcycle clubs, especially the most well known, “Hell’s Angels” George Christie gives you a indept look at the life of an outlaw the ups and downs.

This book is a must read, highly recommended a 10+

having spent the better part of my own life as targeting both the Hells Angles and Mongols as a now retired member of the most corrupt police units B.E.T. ( Biker Enforcement Team) this book is a true account of what it was like.