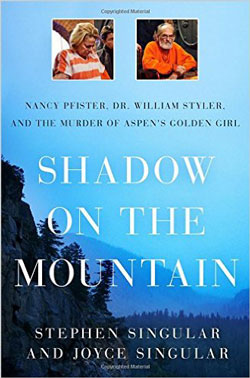

Shadow on the Mountain: Nancy Pfister, Dr. William Styler, and the Murder of Aspen's Golden Girl by Stephen and Joyce Singular is the true crime tale of the murder of Nancy Pfister in the mountains of Aspen, Colorado (Available March 22, 2016).

Shadow on the Mountain: Nancy Pfister, Dr. William Styler, and the Murder of Aspen's Golden Girl by Stephen and Joyce Singular is the true crime tale of the murder of Nancy Pfister in the mountains of Aspen, Colorado (Available March 22, 2016).

Nancy Pfister, heir to Buttermilk Mountain, the world-renowned site of the Winter X Games, was Aspen royalty, its ambassador to the world. She lived among the rich and famous: she partied with Hunter S. Thompson, dated Jack Nicholson, had a joint baby shower with Goldie Hawn, and globetrotted with Angelica Houston. She was also a philanthropist, admired for her generosity. But behind the warm façade, she could be selfish, manipulative, and careless. Pfister enjoyed bragging about her wealth and celebrity connections, but those closest to her, like Kathy Carpenter, Pfister's personal assistant, drinking companion, and on one occasion lover, knew better.

In 2013, after a long fall from grace, Dr. William Styler and his wife, Nancy, relocated to Aspen to reinvent themselves. They'd lived the high life before a misguided lawsuit left them near poverty, and Nancy Pfister was their answered prayer. She took them in, gave them a place to live, and allowed them to launch their new spa business. Everything seemed perfect until Pfister turned on them, making increasingly irrational demands and threatening to throw them out on the street.

When Nancy was found beaten to death in her own home, the Stylers and Carpenter were all under suspicion for the gruesome murder. But in this close-knit, wealthytown set on keeping its reputation and secrets safe from the public eye, the police struggled to solve the mystery of what really happened.

1

Within a few hours, an overwrought Kathy Carpenter would tell the police that on this warmish late February evening in 2014 she’d driven up to Nancy Pfister’s home above Aspen, Colorado. A trust-funder and world traveler in her mid-fifties, Pfister was often gone for months at a time, exploring a distant continent or visiting friends in Hawaii, Thailand, Nepal, the Caribbean, or India. After seven years of a volatile relationship with Kathy and an on-again, off-again business arrangement, Nancy had come to rely on her, leaving her in charge of the house when away. As a teller at Alpine Bank, Carpenter deposited cash or checks for Nancy and watched Gabe, Pfister’s eight-month-old black labradoodle. Some people thought the women were lovers, but others said Nancy was only interested in men.

Set back a hundred yards or so from West Buttermilk Road, the heiress’s secluded residence was encircled by snowfall and thick stands of aspen, their limbs bare in the lingering dead of winter. When Kathy reached the driveway, she turned right and followed a long strip of gravel down to the property. In darkness she opened the front door and stepped inside, scanning the main floor and seeing Gabe, who was always excited by her arrival. Wagging his hindquarters and nodding his head, he came toward her and nestled against her leg. Kathy breathed in the powerful stench of the dog’s mess, scattered around the house, even though one of the windows was open and letting in chilly air. Why hadn’t someone bothered to clean this up?

She moved past Gabe and on past a rarely used billiard table, going upstairs to the master bedroom, with its large walk-in closet filled with clothes, shoes, and Tibetan prayer flags—a space that Nancy called her “special closet.” Glancing around, Kathy noticed that the bed was neatly made, the first thing that struck her as odd. Nancy had never made a bed in her life, leaving such details to other people.

Lifting the bedcover, Kathy saw no sheets on the mattress—another oddity—and the mattress itself was slightly askew. Raising her eyes, she spotted a red smear of what looked like blood on the headboard. She instinctively moved toward the closet, ten feet away from the foot of the bed. A few days earlier, she’d slipped a key into the closet door for Nancy, who was coming home after an extended stay in Australia. Attached to the key was an oval tag with “Owner’s Closet” written across it; both the key and tag were gone. Kathy looked in her purse for the backup key she kept on a lanyard—she’d had a duplicate made last December when Nancy had insisted she change the lock on the closet door—but she hadn’t brought it with her.

She pulled out her cell phone and called her mother, Chris, and then a friend of Nancy’s, Patty Stranahan, telling both the same thing: the house felt weird.

Kathy brought Gabe outside with her and loaded him into her Subaru and took West Buttermilk Road down into Aspen to her small apartment on Main Street, housing provided to her by Alpine Bank. This arrangement had become commonplace in town because service people like Kathy couldn’t afford to live there without assistance. Aspen and environs had America’s most expensive real estate, with the 2014 median listing price for houses or condos standing at roughly $4.5 million. One local residence, the 24,000-square-foot Peak House, rented for $20,000 a day. In 1991, His Royal Highness Prince Bandar bin Sultan bin Abdulaziz, the ex–Saudi Arabian ambassador to the United States, had built a vacation getaway in Aspen’s Starwood neighborhood. Sixteen years later, the prince listed it for $135 million, the nation’s highest-priced private residence. When Bandar was accused of financing the property through $1 billion in bribes he’d received from a British defense company that sold fighter jets to the Saudis, a judge froze his U.S. assets and he had to make do with his other $20 billion worth of investments. The investigation was ultimately dropped.

Nancy Pfister’s relatively modest three-bedroom home was just over 4,000 square feet and had a market value of slightly more than $4 million. She didn’t own the house, but she didn’t rent or lease it, either. The paper on the property was held by NMP Residence Trust, located within the Aspen law firm of Garfield & Hecht, which for decades had handled the Pfisters’ financial affairs. When people spoke of the creation of modern Aspen, they usually brought up Nancy’s parents, Art and Betty Pfister. In 1958, Art was a founding partner of the Buttermilk Ski Area, lately made famous by Shaun “The Flying Tomato” White at the Winter X Games, and by the Special Olympics. Art eventually sold his share of the mountain to the Aspen Skiing Company and his other holdings were developed into the Maroon Creek Golf and Tennis Club. In the past few years, both Art and Betty had died, leaving behind the family fortune and three daughters: Suzanne, who lived across the road from Nancy, and Christina, who’d moved to Denver.

Nancy was by far the most adventurous and unconventional. When Aspenites went abroad and told the natives where they were from, they regularly heard, “Do you know Nancy Pfister?” The Colorado blonde hadn’t merely visited their countries, but had made an immediate and lasting impression. Her curiosity, her utter spontaneity, her hunger for new experiences, and her sunburst smile were all hard to forget. She had friends in the Far East, in South America, and across Europe. She watched the French Open in Paris with Roman Polanski and flew to Africa with Anjelica Huston. Some called her “Aspen’s Ambassador to the World” or “Aspen’s Welcome Wagon” or “Aspen’s Golden Girl.” There were people who called her much less flattering things—but only after they’d gotten to know her and seen the darker parts of her personality.

After retrieving the key from her condo, Kathy headed north out of town and took a left onto West Buttermilk Road, the Subaru winding steeply upward above the Roaring Fork Valley, giving her a spectacular view of Aspen at night. The town was a notch under 8,000 feet in elevation and Nancy’s house was a few hundred feet above that. Homes to the right and left of the road reflected the extreme wealth that had settled into Pitkin County during the past half century.

Kathy pulled into the driveway and parked near the house. Leaving Gabe in the car, she went back inside, walked upstairs, tentatively approached the bedroom closet, and reached for her key. She turned the knob and looked into the large space holding Nancy’s wardrobe, paintings, and other personal effects. Stretched out on the floor was a mostly white long bundle, which could have easily been taken for sheets or clothing, but the smell was so strong that there was no doubt in Kathy’s mind what that bundle was. She bolted out of the room and out of the house.

* * *

“Oh, my god! Help me!” she told the 911 operator, her voice barely audible and at the edge of hysteria. “My friend! Oh, my god! My friend!”

Her call had gone into the emergency center that served both the City of Aspen and the Pitkin County Sheriff’s Office. Because Nancy’s residence was located outside of town, the sheriff’s office had jurisdiction.

Before dialing the number on her cell, Kathy had gotten in her car and driven partway down West Buttermilk Road. She told the dispatcher that she’d just left the Pfister home and was on her way to the police station, fearing that a killer might still be inside the house. The dispatcher ordered her to pull over to the shoulder immediately and to park, which she did.

Sobbing, Kathy said that her friend was wrapped in something “full of blood” and that she’d also seen blood in the master bedroom. When she described where she’d seen it, the word came out hurriedly and awkwardly: she saw it either on the bed’s “headboard” or on the body’s “forehead.” Either way, after peering into the closet, she surmised that Nancy Pfister was covered up in there and dead.

“What is your friend wrapped in?” the dispatcher asked.

“I-I-I don’t know,” Carpenter cried. “I don’t know!”

As the dispatcher questioned her, Kathy blurted out that Nancy had “really pissed them off,” referring to Dr. William Styler III and his wife, Nancy, who until the past few days had been renting Pfister’s house.

The dispatcher again told her to stay put in her vehicle and an officer would be there soon.

* * *

Regardless of what Kathy had seen or what words she’d used about the interior of the closet, her report was essentially accurate. Nancy Pfister, the blonde with the jaunty hats and the explosive grin, the globe-trotter who constantly had a drink in her hand, the woman who’d so easily captured men’s attention in her youth, including several major movie stars passing through Aspen, was now a disfigured corpse, deep into rigor mortis, beaten so badly that she was all but unrecognizable.

No one would have predicted this end for her, and certainly not in her hometown. She’d had such a confident look in her eye, as if her travels had left her wise to the world and always able to avoid trouble.

“I own the Aspen airport,” she liked to brag, when stashing marijuana edibles on board an international flight to countries where the drug could land you in prison, far away from your family’s reputation and resources.

Inside her small mountain town, she was “Aspen Royalty” and felt invulnerable, untouchable, yet she’d acted the same way everywhere. She’d gone abroad without a passport, flown small aircraft in Third World countries, had casual sexual encounters with strangers right after meeting them—and nothing had ever gone wrong. If something was about to go sideways, she’d change her plans and catch the next flight home. For nearly six decades, she’d lived as if she were risk-free, not just in terms of legal and illegal substances, but also in human relationships. Wiggling into and out of them countless times, she never seemed to get damaged in the ways that plagued other people. No matter where she went or what happened, she knew that she could always return to Aspen, her safe haven.

“She was magical,” said one of her female friends. “When you were around her, you could feel that.”

Yet some people in Aspen had long worried that over time the magic had begun to wear off and her allure had begun to diminish; the folks she hung out with now were no longer A-list celebrities, but many notches below that on the social ladder. Her taste for drugs, alcohol, chance encounters with men, and rushing into love affairs with those she barely knew, or a combination of all four, might eventually do her in.

Nancy’s death was instantly a hot topic on Aspen’s Main Street and throughout the Roaring Fork Valley. This was partly because the town hadn’t seen a homicide since 2001 and partly because of the grisly nature of the killing, although law enforcement was being very tight-lipped about exactly how Nancy had been murdered. It was partly because a killer or killers were on the loose, in a community where many didn’t bother to lock their doors at night. And partly because of who had been killed up on West Buttermilk Road: the daughter of one of Aspen’s most respected and historically rooted families, the woman whom some considered the soul or spirit of Aspen, while others looked upon her as a wild child trapped inside the town’s excesses of the 1970s and ’80s, locked into a long-gone era.

Over Easter weekend of 2013, a female producer for the French television show Access Privé (think Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous) had come to town to film a segment on Aspen’s wealth and celebrities. To gain entrée to the best homes and the most famous people, she needed a tour guide, someone who’d been around for decades and knew the territory. With an assist from a pair of Nancy’s friends, the TV program was nudged in her direction and the French producer eventually decided to use Pfister in this role. Nancy took her to the Home Run Ranch, belonging to Goldie Hawn and Kurt Russell; to Owl Creek Farm, owned by the late Hunter Thompson; to Kevin Costner’s residence; and up to the red house owned by Jack Nicholson, whom Nancy had once dated. At Jack’s place, she’d point out the bedroom she’d shared with the movie star. People close to Nancy said that she’d never quite gotten over their romance and still spoke of him wistfully.

The night before the Access Privé shooting, Nancy invited the producer to a party at a home owned by the late printmaker Thomas Benton. One of Nancy’s best friends, Bob Braudis, the legendary ex-sheriff of Aspen, was there, along with some other locals. The boozing and pot smoking went on and on, wowing the French TV exec.

“Zis town is so crazy!” she kept saying. “I love zis town.”

The next morning, Nancy’s eyes were covered by sunglasses as she nursed a serious hangover and moved a bit gingerly, but she emerged from her house on time for the filming. Throughout the day, as she showedAccess Privé the homes of the stars, she offered up her best girly smile and her patented giggle, and at the end of the televised segment, she rode off into the dusk in a horse-drawn carriage on a perfect winter’s eve in the Colorado Rockies, the sunlight fading behind her in the west. With a floppy felt hat—embellished by a red feather—perched on her head and an elegant crimson scarf wrapped around her neck, she sipped a flute of champagne, precisely the way that many would have wanted to remember her. She was so fond of bubbly that some of her pals had called her “Fizz.”

She was having fun and wanted everyone to know it. Nancy was like that and so very different from her two dark-haired sisters, people around Aspen always said. Suzanne and Christina were much more conservative and low-key. Suzanne had worked as a real estate broker and Christina was the president of the Silver Queen Collection of furs, cashmere, linens, and bath products, but Nancy …

She’d never really worked anywhere, but told people that she was an architect or an entertainment producer and she touted herself as a Buddhist, with her Eastern philosophy and Tibetan prayer flags. The contrasts with her sisters went deeper than her looks and beliefs. She acted differently from them in unsettling ways, ways that some people had been worried about for a long time, ways that one day could get her into the kind of trouble she couldn’t escape with a last-minute plane ticket, and ways that her parents and an earlier generation in Aspen would never have condoned—ways that could even get you killed.

Copyright © 2016 Stephen & Joyce Singular.

To learn more or order a copy, visit:

opens in a new window![]() opens in a new window

opens in a new window![]() opens in a new window

opens in a new window![]() opens in a new window

opens in a new window![]()

Stephen Singular is a New York Times bestselling author and Edgar Award nominee. His book Talked to Death was made into the Oliver Stone film Talk Radio. Singular has appeared on Larry King Live, Good Morning America, Court TV, and Anderson Cooper 360.