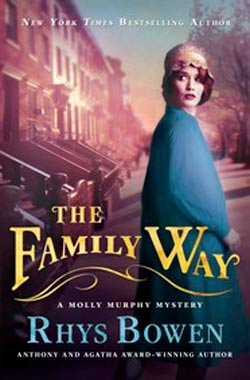

An excerpt of The Family Way by Rhys Bowen, volume 12 of the Molly Murphy mystery series set in New York City in the 1900s (available March 5, 2013).

An excerpt of The Family Way by Rhys Bowen, volume 12 of the Molly Murphy mystery series set in New York City in the 1900s (available March 5, 2013).

Molly Murphy—now Molly Sullivan—is a year into her marriage, expecting her first child, and confined to the life of a housewife. So when a trip to the post office brings a letter addressed to her old detective agency asking her to locate a missing Irish serving maid, Molly figures it couldn’t hurt to at least ask around, despite her promise to give up her old career as a detective. On the same day, Molly learns that five babies have been kidnapped in the past month.

Refusing to let Molly help with the kidnapping investigation, her husband sends her away to spend the summer with his mother. But even in the quiet, leafy suburbs, Molly’s own pending motherhood makes her unable to ignore these missing children. What she uncovers will put her life—and that of her baby—in danger.

Chapter 1

New York City, July 1904

Satan finds work for idle hands to do. That was one of my mother’s favorite sayings if she ever caught me daydreaming or lying on my back on the turf, staring up at the white clouds that raced across the sky. I could almost hear her voice, with its strong Irish brogue, as I sat on the sofa and sipped a glass of lemonade on a hot July day.

Frankly, I rather wished that Satan would find me something to do with my idle hands because I was dying of boredom. All my life I’d been used to hard work, forced to care for my father and three young brothers after my mother went to her heavenly rest. (At least I presume that’s where she went. She certainly thought she deserved it.) And now, for the first time in my life, I was a lady of leisure. Ever since I found out I was in the family way, back in February, Daniel had treated me as if I was made of fine porcelain. For the first few months I was glad of his solicitous behavior toward me as I was horribly sick. In fact I began to feel more sympathy for my mother, who had gone through this at least four times. But then, at the start of the fourth month, a miraculous change occurred. I awoke one morning to find that I felt well and hungry and full of energy. Daniel, however, still insisted that I did as little as possible, did not exert myself, took no risks, and generally behave like one of those helpless females I so despised.

He wanted me to lie on the couch with my feet up and spend my days making little garments. I had tried to do this and the quality of my sewing and knitting had improved, but still left a lot to be desired. Besides, I knew that my mother- in-law was sewing away diligently and that my neighbors Sid and Gus would shower the child with expensive presents.

So this left long hours to be filled every day. Our little house on Patchin Place could be cleaned in a couple of hours. I did a little shopping, but Daniel’s job as a police captain meant that he was seldom home for lunch and sometimes not even for dinner, so little cooking was required. I was glad of this when the weather turned hot at the end of June as my growing bulk meant that I felt the heat badly. Daniel suggested that he could fend for himself just fine and I should go up to his mother in Westchester County, where I’d be cooler and well looked after. I didn’t say it out loud but I’d rather have endured a fiery furnace than a prolonged stay with Daniel’s mother. Not that she was an ogre or anything, but her standards of perfection and her social interactions with members of high society left me feeling hopelessly inadequate. I knew that she was disappointed that Daniel had not made a better match than an Irish girl with no money and no family connections.

She never actually came out and said this, but she made it plain enough. “I took tea with the Harpers yesterday,” she’d say. “I remember that one of the Harper girls was rather sweet on you at one time, Daniel. She’s gone on to make an excellent marriage with one of the Van Baarens. Her parents couldn’t be happier.” And then she’d look at me.

So I was prepared to endure any amount of heat rather than Daniel’s mother. I just wished these last months would hurry up and be over. I put down my lemonade glass and picked up the undershirt I had been attempting to sew. I could see sweaty fingerprints on the fine white cotton and several places where the stitches had been unpicked. I sighed. I just wasn’t cut out to be a seamstress. As a detective I hadn’t done at all badly, but that profession was now closed to me. Daniel had made me promise that I’d give up my agency when we married. I had hoped that Daniel would share his cases with me, that we’d sit at the kitchen table and he’d ask for my opinion. But he had claimed that his recent cases had been too commonplace to be worth discussing or else so confidential that he had to remain tight-lipped about them.

I looked up as the sun suddenly streamed in through the back parlor windows. A sunbeam lit the dust motes in the air and painted a stripe of brightness on the wallpaper. Now this room would soon be too hot for comfort and I’d be banished to the front parlor, dark and gloomy, until the sun set. I got up to draw the heavy velvet drapes across the window and noticed that the lace curtains looked rather dingy. That would never do. Having achieved lace curtains for the first time in my life, I should make sure that they remained a pristine white. I went into the kitchen and brought back a high-backed wooden chair. I proceeded to climb on this with some difficulty, then I reached up to unhook the first of the lace curtains.

I was at full stretch, standing on tiptoe, when a voice behind me boomed, “Molly! What in God’s name do you think you’re doing?”

“Jesus, Mary, and Joseph,” I exclaimed. I teetered, and would have fallen if I hadn’t grabbed at the velvet drape, which held fast. I looked around to see Daniel standing there with a face like thunder.

“The curtains needed washing.” I glared at him defiantly.

“You were risking the safety of our baby for the sake of clean curtains?” he demanded. He came over and helped me down from the chair. “You nearly fell, and what might have happened then?”

“It was only a voice suddenly shouting right behind me that made me lose my balance,” I said. “Until you showed up I was doing just fine.”

He looked at me more tenderly now. “Molly, how many times have I told you to take it easy. You’re in a delicate condition, my dear.”

“Nonsense. Women in Ireland have their babies one day and by the end of the week they’re out helping their man in the fields again.”

“And how many of those babies die? Your mother didn’t live long herself, did she?”

I chose not to acknowledge the truth in this. Instead I said breezily, “Daniel, I feel fine and I’m bored to tears doing nothing.”

He took my arm and led me back to the sofa. “Then invite some friends over to tea. I’ve introduced you to the wives of some of my colleagues, haven’t I? It’s about time you built up a circle of social acquaintances. And there are always your friends across the street,” he added grudgingly, not being as keen as I on my bohemian neighbors.

I sighed. “They’ve gone to stay with Gus’s relatives in Newport, Rhode Island, to escape the heat,” I said. “You remember the mansion with the Roman pillars.”

“Very well.” We’d spent our honeymoon in Newport and it had hardly gone as planned. Daniel pulled up the kitchen chair and sat beside me. “So why don’t you go to my mother as I suggested? You know she’d love to make a fuss of you, and feed you well, and it’s so much cooler out there.”

“Daniel, I’m your wife. My place is taking care of you,” I replied, not wanting to tell him the real reason. Isn’t it amazing what marriage does to a woman? I was finally learning to be diplomatic. I was one step away from being simpering.

“I can fend for myself quite well. I’ve been doing it for years.”

“But you work long hours, Daniel. It’s not right that you should come home to no supper and no clean clothes.”

He wagged a finger at me. “What have I been telling you for months? Then this is the perfect time to get a servant.”

I sighed. “Daniel, let’s not go through that again. We really don’t need a servant. This is a small house. I’m used to hard work. I’m happy to cook and clean for you, and for our baby too. If a few more children start to come along, then I may need some help, but for the present. . . .”

“It’s not just the amount of work, Molly. It’s the principle of the thing. A man in my position should have a servant. When we start entertaining more, it wouldn’t be right that you’d have to keep disappearing into the kitchen to see to the dinner. I want you to be the gracious hostess.”

“Oh, I see,” I said, my rising temper now winning out over my newfound meekness. “It’s not concern about me at all, is it? You’re worried about how you appear in the eyes of society.”

He looked at my expression and took my hand. “Molly, this is not for myself, it’s for us. Everything I do from now on is for my family. I want the best for us and for our children. I want to rise in the world, it’s true, and I’ll be judged on the kind of home I keep and the people I associate with.” He paused. “And I want the world to see that I married a beautiful woman.”

I had to smile at this. “You may have been born in America, Daniel Sullivan,” I said, “but you’ve certainly inherited your share of Irish blarney!”

He smiled too. “I am thinking of you, Molly. If you’re up all night with a crying baby, you’ll appreciate a girl taking over from you so you can get your rest. You say you’re bored and have nothing to do—well, what better time to train a servant so that she knows your wishes and how this household works by the time the baby arrives?”

I hesitated, then said, “Well, I suppose I could start making inquiries.”

He jumped to his feet. “I know,” he said. “Why don’t I write to my mother and ask for her help in this?”

Now my hackles truly were rising. “Why does your mother have to come into every aspect of our lives?” I demanded. “Do you not believe I’m capable of finding a servant for myself?”

“Of course you are. I’m simply trying to spare you extra toil and bother. I don’t want you traipsing around the city at this time of year. They say there is typhoid in Brooklyn this summer and who knows when that will spread across the East River. We can’t be too careful in your current condition.”

“Not all employment agencies are in bad neighborhoods,” I said. “I went to a snooty one myself when I was newly arrived here and needed work.”

He frowned. “I’m not sure we could pay the rates of a snooty agency. And I’m concerned that lesser agencies don’t always vet their girls well enough. I don’t like the idea of hiring a girl newly off the boat. How do we know she’ll be trustworthy?” He put a hand on my shoulder. “My mother knows the right sort of people, Molly. She’ll be able to ask around and get recommendations. New York is a big place and full of crooks and swindlers, as I know only too well. We have to be extra cautious about who we allow into our house. One of the gangs would just love to place an informant in my home and have my comings and goings monitored.”

“But surely, if I go through a reputable agency . . .” I began, but he cut me off. “Let’s try my mother first and see who she can come up with, shall we? Then you can go out to her to interview likely girls and choose the one you like.”

I wasn’t at all happy with this. If the gangs wanted to place a spy in our home to monitor Daniel’s movements then it was just as likely that Daniel’s mother would like to place her own spy to monitor mine. But I could hardly express that sentiment to Daniel. Men are funny about their mothers, seeing them as one step away from sainthood. So I told myself silently that I didn’t have to choose any girl I didn’t like and in the meantime I’d do my own asking around.

“I’ll write the letter now,” Daniel said, “if you’d be good enough to make me a quick bite to eat before I go back to work.”

With that he went through to his desk in the front parlor that had now become his study, and I went to my rightful place in the kitchen, trying to put aside thoughts that a woman’s lot in life was not a fair one. I made him a cold beef sandwich and some pickled cabbage, and was pouring him a glass of lemonade when he returned with the letter.

“This can go out with the three o’clock mail if you’ll take it to the post office for me.” He sat and worked his way quickly through the sandwich. “I may not be home until late tonight,” he said.

I pulled up a chair and sat opposite him. “Difficult case?” I asked, trying to sound casual.

“Several at once, that’s the problem. I like to devote all my energy to one thing at a time, not to be running hither and yon. But the powers that be have saddled me with something I’d rather avoid.”

“Maybe I can help,” I suggested. “If you’d care to discuss them with me.”

He shook his head. “Nothing to discuss. No clever murderers to be outwitted. Just various types of petty crooks making life unpleasant for the populace.” He pushed his plate away. “Very nice. Thank you, my dear. And you will make sure that letter gets to the post office, won’t you?” He kissed my forehead and was gone.

I cleared away the remains of the meal and looked at that letter lying on the table. I didn’t have to mail it, did I? But then I realized that I did. There has to be trust between husband and wife, however abhorrent it was to me that the task of finding my servant was being left to his mother. I glanced at the fruit bowl and saw that we were down to a single plum. Fruit was one of the things I’d been craving recently so I decided to treat myself to some peaches if I had to go out. I pinned my straw hat to my flyaway hair, put on my cotton gloves, and out I went.

The heat came up from the cobbles to hit me, almost as if someone had opened an oven door. I hugged the side of the alleyway that was in shade and made my way slowly to Sixth Avenue. I went into the post office and dropped the letter into the outgoing mail slot. I was about to leave when a large florid man leaned across the counter toward me.

“Excuse me, ma’am,” he said, “but weren’t you the young lady that used to collect the mail for P. Riley Associates?”

“That’s right,” I said, P. Riley Associates being the name of the small detective agency I had inherited after the murder of Paddy Riley. “But that agency is no more and the post office box has been closed.”

“I know that,” he said. “It’s just that a letter came in addressed to that establishment only a week or so ago, and I didn’t quite know what to do with it, no forwarding address having been left with us. So it’s still sitting there and I thought that maybe you’d know where to deliver it. Hold on a minute and I’ll fetch it for you.”

He disappeared into a back room and then returned, panting and red-faced, but triumphantly waving an envelope. “Here you are. So maybe you’ll see that the right party gets his mail then.”

“I will,” I said. “Thank you.”

With the letter in my gloved hand I went out into the heat of Sixth Avenue. I walked until I was standing in the shade of a sycamore tree before I stopped to examine it. Of course I knew that P. Riley Associates was no more, and that I had promised Daniel I would give up all such nonsense when I married him. That meant that I should throw the letter straight into the nearest rubbish bin. But then I told myself that it might be a belated payment for services rendered long ago and I couldn’t risk throwing good money away. I looked at the envelope and saw the stamp with King Edward’s head on it. From England then. I opened the envelope and found no money but a single sheet of cheap lined paper, such as one would find in an exercise book. I also saw from the address at the top that the letter came not from England but from Ireland, from County Cork.

Dear Sir or Madam:

We are but simple folk and can’t pay you much money, so if you’re one of these big swank detectives then I’m thinking you’ll not want to be bothered with the likes of us. But we’re more than a little worried about our niece Maureen O’Byrne. She sailed for New York on the Majestic out of Queenstown just under a year ago, hoping to make a better life for herself in your country. Indeed things seemed to fall into place instantly for her. She hadn’t been there more than a week or two when she wrote to us saying that she’d landed herself a good situation as under-parlormaid with a Mrs. Mainwaring and she hoped soon to be sending money home when she’d paid off her passage.

She had not given us an address to write to, so we could only wait for more news. Well, we waited and waited but heard nothing more. So now a year’s coming up and we’re concerned about her welfare. She was always a good girl and devoted to her uncle and me, as we were her closest relatives since her poor mother and father died. Something must have happened to her, or she would have written, I’m absolutely sure. Even if she couldn’t send any money she would have at least written a note at Christmastime.

As I said, we are not wealthy folks and I have no idea what your usual fee might be, but we’ve a little set aside for our funerals and we’re willing to do what’s necessary to learn about our Maureen. Anything you can do to help will be appreciated. Please reply to the above address and God love you for your efforts.

Yours faithfully,

E. M. O’Byrne (Mrs.)

P.S. I have enclosed a picture of Maureen to help you with your inquiries. As you can see, she’s a pretty girl, dainty, almost fairylike. We used to tease her that she was a changeling as we’re all heavyset and dark in the family except for her.

Chapter 2

I stood staring down at the picture of Maureen. It had obviously been cut from a family group and showed her stiff, uneasy, and unsmiling; her hands folded in an unnatural position. Her hair was light, but it wasn’t possible to tell the true color. I slipped the picture back into the envelope then reread the letter. By the time I had finished reading, my head had started buzzing with ideas. The missing girl had done something she was ashamed of and didn’t want them to know. She’d run off with an unsuitable man, or she’d been sacked from her situation in Mrs. Mainwaring’s household and didn’t want to write until she had found herself a new post. If I could locate this Mrs. Mainwaring, no doubt this matter could be solved quickly. It shouldn’t be too hard—Mrs. Mainwaring must be a lady of some substance if she ran a house hold big enough to employ more than one parlormaid. And I knew people who moved in those circles. The first person to try should be my old friend Miss Van Woekem—she knew the Four Hundred personally. Or maybe some of my friend Emily’s Vassar pals, or of course Gus came from a most distinguished Boston family who would have connections in New York. It wasn’t definite that the lady lived in New York, but given that the girl landed here and found a situation immediately, one could surmise….

A horse and cart lumbered past, the poor horse with his head straining forward and breathing heavily as he attempted to drag a dray piled high with barrels. The clop of hooves and the rumble and rattle of the cart so close to me broke my train of thought and made me step back hastily from the curb. Then I realized that it was no use surmising. I would not be taking on this case. I had given up my detective business and promised Daniel that I would never again involve myself in stupidly dangerous situations. As hard as this was for me, I could see his point of view: I had narrowly escaped death on several occasions. I’d even suffered a miscarriage once that I had never found the courage to tell him about. He had been unjustly jailed at the time and in no position to marry me. As these thoughts passed through my mind I admitted that I had experienced some very dark hours. I had taken stupid risks. I was lucky to be alive and to be married to the man I loved with a bright future ahead of me.

I’d take the letter home, show it to Daniel, and ask if he knew of any reputable private detectives who might want to take on the job. I stopped at my favorite greengrocer on the corner of Ninth Street and bought a pound of peaches and some salad for Daniel’s supper, since it would be too hot to think of cooking much. I looked longingly at those peaches in my basket, tempted to eat one on the spot, but reminded myself that the respectable wife of a well-known police captain does not behave like a street urchin. Instead I joined the throng attempting to stay in the shade under the elevated railway tracks, and was trying to avoid being bumped and jostled when I heard my name being called.

I stepped out into the sunlight, looked up, and saw a delicate vision in pale lilac waving at me. She seemed almost unreal, so out of place among the drab colors of the sturdy house wives and laborers that I had to look twice before I recognized her. It was Sarah Lindley, fellow suffragist friend of Sid and Gus. In spite of the fact that she came from an upper-class and wealthy family she was not only passionately involved in the suffrage movement but had been volunteering at a settlement house in the slums of the Lower East Side. She looked both ways and dodged between a hansom cab and a big black carriage to come to me.

“Molly, how lovely to see you,” she said, giving me a delicate kiss on the cheek. “And how well you look. Positively blooming. How many months to go now?”

“Two and a half,” I said, “and it can’t go by quickly enough for me. I find this heat unbearable.”

“I know. Isn’t it just awful?” She brushed an imaginary strand of stray hair back under her lilac straw hat.

“Surely you could escape from it,” I said. “Don’t your folks have a country estate? Or weren’t you supposed to be making a European grand tour?”

“Already accomplished, my dear,” Sarah said, linking her arm through mine as we started to walk together. “We went in May. France, Italy, Germany, you name it, we were there. Every art gallery and palace in creation. All very lovely, but not a single prince or count asked for my hand so mama came home most disappointed.”

I glanced at her and we exchanged a grin. “I don’t imagine you’re in any hurry to marry after what you went through last year, are you?” I asked. Her last fiancé had turned out to be what we would have called a rotter who came to a bad end.

“Exactly,” she said. “And I want to be like you. I want to marry for love. Mama is all for a good match, but I don’t see why one should be unhappy for one’s whole life just to have a title or a castle or something.”

“So what are you doing in this part of the city?” I asked.

“Coming to pay a call on your dear neighbors,” she said. “I haven’t seen them since I came back from Europe and I’m dying to regale them with all my stories. I know they’ll love to hear about the fat German count who trapped me in the hotel elevator in Berlin and tried to kiss me.”

“How disgusting. What did you do? Scream for help?”

“Absolutely not, my sweet. I stuck the tip of my parasol into his foot. With considerable force. You should have heard him howl and hop around.”

I laughed. “Sid and Gus would be proud,” I said, “but I’m afraid you’ve come on a wasted journey. They are not home. They went to stay with Gus’s cousin in Newport.”

“Oh, the dreaded Roman mansion.” She laughed. “I wonder what made Gus endure that again. I thought she couldn’t stand that particular cousin.”

“I gather they were prepared to suffer the cousin for the sake of sea air,” I said. “It really is devilishly hot in the city. As I said I’m surprised you haven’t escaped.”

“Devotion to duty,” Sarah said. “One of our volunteers at the settlement house is getting married so I promised to take over her shifts.”

“You’re still working at the settlement house?”

“I am. It’s hard work, but it brings me great satisfaction to be able to make a difference in the lives of those people. We’ve expanded our educational programs and we’re teaching so many poor mothers about hygiene and good nutrition. That’s become my little pet project, actually. I love going out into the tenements and helping people. You’d be amazed how many mothers haven’t the slightest idea about how to look after their babies—they let the little dears crawl around on absolutely filthy floors and put anything they find in their mouths and they even give them rags soaked in gin to keep them quiet.”

“You’re doing a wonderful job,” I said.

She wrinkled her little button of a nose. “Mama doesn’t see it that way. I have to endure a constant barrage of comments about my chances of marriage slipping away and the bloom fading on the rose and the horrors of impending spinsterhood. But frankly, Molly, I’d be quite happy not marrying and doing this kind of work all my life. What’s so wrong with it?”

“It isn’t what your mother had planned for you, that’s what,” I said. “Every mother wants her daughter happily married and lots of grandchildren. You should see how excited Daniel’s mother is about the arrival of the baby.”

“And your mother? I presume she’s still at home in Ireland?”

I shook my head. “My mother died when I was fourteen. My father’s dead too. I have a brother who was part of the Republican Brotherhood, hiding out somewhere in France, and a younger brother still in Ireland but that’s all. No real family anymore.”

She touched my arm. “Poor Molly. How sad for you.”

“I don’t mind,” I said. “I’ve got Daniel, and Sid and Gus have become like family to me. I’m so sorry they’re not at home. I don’t know when they plan to return. Would you care to come to my place for a cup of tea or a lemonade since you’re in the neighborhood?”

“How kind of you. I’d love to.”

We turned, arm in arm, from Sixth to Greenwich Avenue and from there into Patchin Place, teetering on the cobbles in our dainty shoes. The house was now uncomfortably hot so I led Sarah though to our tiny square of back garden, where I had set a wrought iron table and two chairs in the shade of a lilac tree, then brought out a jug of lemonade and a plate of biscuits I had made a few days previously. Sarah clapped her hands and laughed in delight.

“Molly, you have become so domesticated. Look at you, lady of the house and soon-to-be mother. Did you ever imagine when we met last year that your life could change so dramatically?”

“It certainly is changed,” I agreed as I poured the lemonade.

“How relieved you must be that you are no longer in danger and working in such uncomfortable circumstances,” she said.

I hesitated. “Sometimes I feel that way, but I’m used to hard work, and I’m afraid I enjoyed the excitement of my job too. I find my present condition rather boring. I wasn’t raised to leisure like you so I’ve no idea how to fill idle hours.”

She took a sip of lemonade. “I was raised to leisure, as you say, but I have always rebelled against it. Croquet matches and coffee mornings seem such a waste of time to me. And all those discussions about new hats and dressmakers. I never could abide them. That’s why I went to work at the settlement house and found like-minded people.” She looked up suddenly from her glass. “You could always come and help me if you’re bored,” she said. “I’m sure you’d be splendid at educating families in the tenements on hygiene and I’d certainly relish a companion with me.”

“I would jump at a chance like that, but I’m afraid Daniel wouldn’t agree. He’s treating me as if I’m a dainty little flower at the moment and he’s terrified I’ll catch some awful disease if I venture into the slums.”

Her face grew somber. “Well, he does have a point there. Remember that terrifying typhoid outbreak a couple of years ago? They are saying there is already typhoid in Brooklyn this summer and it can easily spread across the river. And there is always cholera in the hot weather. So maybe joining me wouldn’t be such a good idea, Molly.”

“Don’t you fear for your own health?”

She laughed. “Me? I may look dainty, but I’m as strong as an ox. My brothers all came down with all the childhood diseases when we were young, but not I.”

“I was that way too when I was growing up, but I confess that I was horribly sick in the early months of my condition and for the first time in my life I did feel like a delicate china doll who needed looking after. Thankfully that has passed and I’m raring to go again. Daniel chided me earlier today because he found me standing on a chair, taking down the net curtains to launder them.”

“I think I might have chided you too,” she said.

“I need to keep busy, Sarah.”

She looked thoughtful. “If you have time on your hands—you could always help our suffrage cause. I know you are a fellow supporter.”

“I am, most definitely, but I don’t think I’m up to marching and carrying banners at the moment.”

“Of course not. But we always need help with flyers and brochures to be handed out. You could assist with things like that, couldn’t you?”

“I could,” I said.

“We’re having a meeting next week to plan strategy. Do you think you can join us?”

I started to say that I’d have to confer with Daniel first, but then the old Molly resurfaced. “Yes, I’d like to,” I said. “As long as it’s not at a time when I should be cooking Daniel’s dinner.” I saw her face and added swiftly, “He works such long hours that I like to make sure he has a proper meal when he gets home.”

She nodded, accepting this, then put down her glass. “I should be making my way to the settlement house,” she said. “We have a couple of new volunteers and I’m afraid they both fit the expression, ‘The spirit is willing, but the flesh is weak.’ They love the idea of serving the poor, but they don’t actually want to scrub floors and make beds.”

We both laughed as she got to her feet.

“I expect it’s hard for people in your station to find themselves in such different circumstances for the first time,” I said. “I don’t suppose they’ve ever scrubbed a floor before.”

She nodded agreement. “It is a shock when you first start and when you find your first bedsheet with fleas and lice all over it. But you soon get used to it. And it’s so worth it when you see the change in the young women who come to us.”

“Where do they go when they leave you?” I asked.

“We try to find domestic situations for those who are suitable. Not all of them are, of course. Those who were ladies of the night or drug fiends don’t take kindly to our ministrations on the whole.”

“And what happens to them?”

“I’m afraid they go back onto the streets, and probably will wind up floating in the East River someday.”

I stared at her, wondering how such a delicate creature could discuss such matters calmly. Most young women of her class would swoon at the words, “drug fiends.” But as I watched her open the back door and step into the house an idea was forming in my mind. “So some of these girls go into domestic service,” I said, following her down the narrow hallway. “Do you place them yourselves?”

“We usually send them to an agency,” she said. “We simply don’t have the time to handle such matters.”

My eyes lit up. “Then we may be able to help each other. Daniel has been adamant that we hire a servant—more for his status than for me, I suspect.” I smiled. “He has just written to his mother to ask her for recommendations, but I’d rather choose my own girl if she’s going to live in my house and work for me. Do you have anyone who might fit the bill at the moment?”

She paused, her hand on my front door knob, thinking. “Not really,” she said. “But the agency that we use might be able to recommend a girl for you. They are most reliable and thorough. I’ll take you and introduce you if you like.”

“That would be splendid,” I said. “Where is this agency?”

“It’s on Broome Street, not far from the Bowery. If you’ve nothing to do right now, I could introduce you on my way to work.”

Loathe as I was to step out into that heat again, I wasn’t going to turn down this chance. “Most kind of you,” I said. “I’ll fetch my hat and gloves.”

“What do you think?” I asked as we reached the entrance to Patchin Place. “Should we chance the Sixth Avenue El and then walk along Broome or should we go across to Broadway and ride the trolley?”

“At this time of day they are both likely to be packed,” Sarah said. “Not a good idea in your delicate condition. We’ll take a cab.”

“A cab? But surely . . .” I began, but she was already stepping out into traffic, waving imperiously with her little gloved finger.

“There are some privileges of the rich that I still enjoy,” she said. “And one of those is taking cabs whenever necessary. In fact Papa insists that I take cabs anytime I’m in undesirable parts of the city. He thinks I’m in constant danger of being captured and whisked off to white slavery.” And she gave a gay little laugh as the cab came to a halt beside us. I had to admit I was glad not to have to face a crowded rail car and the odor of sweaty bodies, my nose having become rather sensitive of late.

The cabby looked surprised when Sarah gave him the address. “Are you sure that’s where you want to go, miss?” he asked.

“Quite sure, thank you,” Sarah replied crisply.

We set off at a lively clip. I put my hand into my purse to find my handkerchief and my fingers closed around the letter. I pulled it out. “Tell me,” I said. “You don’t happen to know a Mrs. Mainwaring, do you?”

“Mainwaring? I don’t think I do. Are they a New York family?”

“I couldn’t tell you. I’ve just received this,” I said and handed her the letter. She read it. “I thought you’d given up detecting work,” she said.

“I have, but I can’t help being curious. If the Mainwarings had turned out to be a well-known New York family, I could have made inquiries and maybe been able to give these Irish folk an answer to their concerns.”

“The fact that I don’t know them doesn’t mean that they are not New Yorkers,” Sarah said. “We are not among the Four Hundred, you know. Daddy started off in trade, which has limited our social rise, much to Mama’s annoyance. And these Mainwarings could be fellow members of the middle class who have now made enough money for a big house and plenty of servants. Besides,” she handed me back the letter, “you don’t know that Mrs. Mainwaring does live in the city, do you? She might live anywhere.”

“The fact that this Maureen found a situation so quickly after arriving in New York indicated to me that the family must be local. She’d either have seen an advertisement or visited a local agency like the one you are taking me to.”

Sarah nodded. “Of course people from all over the country advertise in the New York newspapers. she might have seen an offer of employment in Pennsylvania or California for all you know.”

I shook my head. “I can’t see an Irish girl fresh off the boat being willing to set out for California, not knowing about the people she was going to.”

“It’s a wild goose chase, Molly.”

“I know, and one I shouldn’t be undertaking. But I just thought that if it might be easily solved, then I’d solve it and put the poor woman’s mind at rest.”

“Your husband would not take kindly to your traipsing around New York, I fear.”

I chuckled. “He certainly wouldn’t. But if this agency finds me a good servant, then I’ll have even more time on my hands, won’t I?”

She returned my smile. “Molly, you’re incorrigible. No wonder Sid and Gus like you so much.”

The cab had slowed to a crawl as it entered the Bowery and had to follow a slow-moving procession of horse-drawn vehicles being forced into the curb to get around a stopped electric trolley. Sarah tapped imperiously with her parasol on the roof of our cab. “It’s all right, driver. You can let us disembark here. It’s quicker to walk the rest of the way.”

The driver jumped down to help us from the cab. “You’re sure you’ll be all right, miss?” he said again. “Watch out for pickpockets around here, and less savory folk too.”

“Don’t worry, I come to this part of the city every day,” she said. “I work in the settlement house on Elizabeth Street.”

“Well, blow me down,” he said, mopping his brow with a big red handkerchief. “Good luck to you then, miss.” He looked at the coin she had given him then tipped his cap. “And God bless you too.”

Sarah slipped her arm through mine and steered me through the traffic. We had to break into a sprint as a trolley car came toward us at full speed, its bell clanging madly. One always forgets how fast mechanized vehicles can go. Once on the other sidewalk we were in the shadow of the El and had to force our way among the housewives shopping for tonight’s meal, children getting out of school, and factory workers coming off the early shift. When we turned into Broome the scene was even more chaotic with pushcarts lining both sides of the street and the air resounding with the cacophony of hawkers calling their wares, children shrieking at play, and the ever present Italian organ grinder on the corner, cranking out a lively tarantella. Sarah seemed impervious to it all as she proceeded briskly, pushing aside ragged children and shopping baskets. She was moving at such a great pace that I found it hard to keep up with her and almost collided with a nun, bearing down from the opposite direction. She was wearing a black habit with a cape over it and carried a shopping basket over her arm. The habit was topped off with a peaked bonnet that jutted out, hiding her face in shadow, apart from a long nose that protruded, giving the impression of a black crow.

“Sorry, Sister,” I muttered, remembering the trouble I had gotten into at school when I’d run around a corner during a game and knocked one of the nuns flying.

“No harm done. God bless you, my dear,” she said softly, then crossed the street nodding to two other nuns in severe black habits topped with white coifs who were chatting with a priest and couple of round, elderly women.

“I’m glad I’m not a nun,” Sarah said, echoing my thoughts. “To be wearing all those garments in this weather must be unbearable.”

“They’re probably so holy they don’t notice,” I replied with a grin.

A bell started tolling, a block or so away. The little group broke apart and looked up. The two women crossed themselves. The priest nodded to them and then started walking briskly toward that tolling bell. The crowd on the sidewalk parted magically to let him through. It was clear that the Catholics held sway in this part of the city.

Sarah pulled me out of the stream of the crowd. “Ah, here we are,” she said, stopping at a dark entryway. “It’s on the second floor. Are you able to make it up the stairs, Molly?”

“Yes, of course.” I peered up a long, narrow flight of stairs, then added, “I’m not quite an invalid, you know.”

Up we went. I found it more of an effort than I had expected and that long dark stair seemed to go on forever, but I tried not to let Sarah see that I was out of breath and perspiring by the time she tapped on a dark wood door and then ushered me inside.

I had been to employment agencies myself when I was first looking for work in the city. They all seemed to have been staffed by haughty dragons of women, but the white-haired, soft-faced lady behind the desk could not have been nicer. She listened to my request then nodded. “You’ll be wanting someone who has experience with babies then. Most of the girls we see don’t have much of a clue. Oh, to be sure they’ve helped look after siblings, but their ideas on safety and cleanliness leave much to be desired. So let me give the matter some thought. How soon would you want the girl?”

“There’s no hurry,” I said. “I want someone who’ll be just right. I’d rather wait.”

“Of course you would.”

“So did you already place Hettie Black, Mrs. Hartmann?” Sarah asked.

“Oh, yes. Snapped up instantly. She would have been good,” Mrs. Hartmann said. She had me write down my name and address. “I’ll have a note sent to you the moment I find a suitable girl,” she said.

We were about to leave when it occurred to me that Mrs. Hartmann was the perfect person to ask about Maureen O’Byrne.

“You keep a list of past clients, presumably?” I started to say when there came a scream from the street below.

“My baby! Someone has taken my baby!”

Copyright © 2013 by Rhys Bowen

Rhys Bowen is the author of the Anthony and Agatha Award–winning Molly Murphy mysteries, the Edgar Award-nominated Evan Evans series, and the Royal Spyness series. Born in England, she lives in San Rafael, California.

Dead mother and insufferable mother-in-law. Good combination for a pregnant lead character!

pick me…i would love to read this

I’m about halfway through Rhys’ “Evan Evans” series, and have purchased but not yet read the first “Molly”. I like Ms. Bowen’s style!

Molly is a strong female character. It’s nice to see her stickling to her work while waitinig for her child to arrive.

Count me in….

Read one of the first books . Love period mysteries. Looks like I will need to look for the rest in the series. Count me in.

[b]If you’d like to enter for a chance to win:[/b]

[color=#b22222][b]This one IS NOT a comments sweepstakes, so comment away–please!–but also make sure you click the link in the post above to enter![/b][/color]

Good Luck!

I would love to read the book

I love the characters on this book – I hope I win 🙂

I adore the time period and the mystery aspect of this wonderful

sounding book!

Many thanks, Cindi

jchoppes[at]hotmail[dot]com

I like historical fiction about women.

Irish, period piece, expectant woman with a strong personality. What a combination. This is going to be good.

Adding to the TBR list – sounds really good.

sounds good

Sounds good, count me in! Is this how we enter?

@frogz60:

[b]If you’d like to enter for a chance to win:[/b] [b]This one IS NOT a comments sweepstakes, so comment away–please!–but also make sure you follow the link (at the end of the post) above that says CLICK TO ENTER![/b] Good Luck!

I’d love to read this!