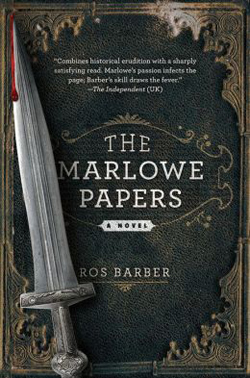

The Marlowe Papers is a historical novel told in poems about the life and mysterious “death” of Christopher Marlowe (available January 29, 2013).

The Marlowe Papers is a historical novel told in poems about the life and mysterious “death” of Christopher Marlowe (available January 29, 2013).

D e c i p h e r e r s

I’ll write in code. Though my name melts away,

I’ll write in urine, onion juice and milk,

in words that can be summoned by a flame,

in ink as light and tough as spider silk.

I’ll send a ream of tamed rebellious thought

to seed a revolution in its sleep;

each letter glass-invisible to light,

each sheet as blank as signposts are to sheep.

The spy’s conventions, slipping edge to edge

among the shadows, under dirty night,

mislead the search. To fool intelligence,

we hide our greatest treasures in plain sight.

This poetry you have before your eyes:

the greatest code that man has yet devised.

C a p t a i n S i l e n c e

We dock in darkness. The skipper’s boy dispatched

to find our lodgings. Not a town for ghosts,

and with no wish to be remembered here

I’m wrapped in scholar’s garb, the bright man’s drab.

A quarter-moon is rationing its light

to smuggle us ashore without a fuss;

the fishermen are far away from port,

their wives inside and unaware of us.

You know I’ve come this way before; not here,

but in this manner, come as contraband

under the loose concealing cloak of night,

disguised as something of no interest,

as simple traveller. A man of books:

which words will make him interesting as dust

to folk who cannot read and do not care

they sign their papers only with a cross.

My name means more, and yet I shrug it off

like reptile skin, adopt some alias

that huffs forgettable, to snuff the flame

that now would be the death of me. Anon,

now Christopher is too much cross to bear.

The skipper calls me only with a cough.

Lugs, with his lanky son, my trunk of books.

No prop. For books will be my nourishment

in the sightless days without you. And if I

feel strange, or wordless, they will anchor thought,

ensure my brain is drowned in histories

that help me to remember who I am.

The skipper leads as shadows bolt from us

and streets fall back. And in his torch’s flame

a flicker of the tongue that can’t be bought,

which pirates sliced to secrecy. The rest,

that part he’d curl to make his consonants,

is long since fish-food on the Spanish main.

The boy speaks for him when we reach the door.

We’re hurried in, ‘Entrez,’ as though a storm

is savaging the calm still tail of May

and has the oak trees shaken by their roots.

The woman might be forty-five, or twelve.

A calculated innocence, a face

so open blank, it seems revealing as

it hides itself. This woman’s learnt to blanch

as bones will bleach when left to drink the sun,

as death will creep a pallor into skin

at just its mention. Clothed in widow’s weeds,

soft fingers straighten for gold. ‘Un angelot.’

Two months of food for sticking out her neck

for an Englishman. The payment’s hidden where

she’s still half warm. ‘So you will sleep above,’

she states as if she questions us, ‘the room

that slopes for Captain Silence and his boy.’

They heft my trunk upstairs between them, just.

‘The less we say, the better,’ she begins.

‘You want some ale? You’re thirsty? Or there’s sack

if you need something stronger.’ Then she pales,

as if she is reflecting me. Some look

betrays my loss to her, and in a blink

her loneliness has fastened on to mine.

‘You learnt the tongue from Huguenots?’ She nods

and answers her own question. ‘That is right.

And you. You are a religious man? But, no,

forget I ask you anything.’ In truth,

I am a scholar of divinity

and study the divine with open eyes.

Beyond all question, I would give her truth;

and yet, I cannot save her if I speak.

‘My husband was an Englishman, like you.

Or not like you. He had no love of books.

Ballads he liked. He used to sing this one—’

Her brain defends itself by giving way.

‘I don’t remember it.’ But here, her eyes

brim with the silence, break their trembling banks

as though she heard his funeral song. Then he,

her husband, a growl, is whispering in her ear

the rudest ballad he knows, clutching her waist

to spin her for a kiss. And then he’s gone,

and we are momentarily with ghosts.

‘Forgive me,’ she says. ‘The silence is poisonous.’

Upstairs, I’m with her still. She’s through the wall,

the spectre of a woman I might touch

on any other night but this. I don’t

undress so much as loosen up a notch,

for comfort now would later be exposed,

a gift to spot and clear as light to slay;

and bad enough, I’m running for my life

without my skin a beacon for the moon,

a human sheath that swallows blades. I sit

laced in my boots, my stomach tight, my ears

so strongly tuned they model sight from sound.

Next door, the widow braves into her gown

and lies awake. She listens to the house

and reads the whispers that pronounce her safe

though I would have her sacrificed for love.

I know her stares are pulling at the wall

I’m on the other side of, and her bed

feels colder for the want of me. And yet,

as time goes on, she’s bidding me adieu.

A woman’s skin might send a man to sleep,

but I must twitch and listen to the night

say Nothing’s here. The moon is out of sight

and something gnaws now, in the walls. I write,

the extra tallow that I paid her for

illuminating every sorry word.

How we are trapped in silence; how this night

has brought a silent shipwreck to her shore,

how silence unites us as it chokes us off,

how thick the silence hangs around the door

that dogs might almost sniff it, and the causes:

cutlass, lies or longing. Gathered here,

awake, or sleeping aware, are three full-grown

examples of the muted. And the boy

fathered by silence, slight and safely bred

to keep his trap shut. How the silence grows,

how it wraps around the house like sealing snow

though we are in the final day of spring.

Silence surrounds the men of deepest faith

and, listened to, may call a man to prayer.

I pray that no one follows us tonight;

that in England, rural keepers of the peace

are kept bewitched by corpse and candlelight;

I pray those men are instantly believed

who, having played my dark and murderous friends,

have stayed to stay the executioner’s hand;

I pray my soul’s absolved in all the lies

that tumble slick as herring from their tongues.

I pray, my friend, you’re warm and safe at home,

that doors remain unkicked and truths untold

and we have silence when the daylight comes.

Copyright ©2012 Ros Barber

For more information, or to buy a copy, visit:

opens in a new window![]() opens in a new window

opens in a new window![]() opens in a new window

opens in a new window![]() opens in a new window

opens in a new window![]() opens in a new window

opens in a new window![]() opens in a new window

opens in a new window![]()

I don’t mind this story, so long as this book is just for fun and not another “serious” attempt to claim Shakespeare was a fraud, like “Anonymous”. That movie, sponsored by the Oxfordian society, was just rubbish. As to Marlowe, I will only say he actually had a Cambridge education and was one of the “University Wits”, and his subjects and style were completely different from Shakespeare. By contrast, due to the social downfall of his father John, a recusant Catholic, Shakespeare did not quite finish his education at King’s New School in Stratford.

I would enjoy reading this one. I’d also recommend the bio, Christopher Marlowe Poet & Spy.

Poets and spies-Yes!