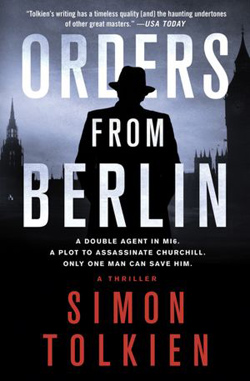

Orders from Berlin by Simon Tolkien is the third Detective Trave historical thriller (available December 11, 2012).

Orders from Berlin by Simon Tolkien is the third Detective Trave historical thriller (available December 11, 2012).

It’s September of 1940. France has fallen and London is being bombed day and night. Almost single-handedly Winston Churchill maintains the country’s morale. Britain’s fate hangs in the balance and the intelligence agencies on both sides of the Channel are desperate for anything that could give them the edge.

Albert Morrison, ex-chief of MI6, is pushed over the banister outside his London apartment. He falls to his death at the feet of his daughter, Ava, but it is too dark for her to see the attacker before he escapes. Two Scotland Yard detectives attend the crime scene: Inspector Quaid and his junior assistant, Detective Trave. Quaid is convinced that this is a simple open-and-shut case involving a family dispute. But Trave is not so sure. Following a mysterious note in the dead man’s pocket, Trave discovers that Morrison was visited by Alec Thorn, deputy head of MI6, on the day of his death. Could Thorn—who is clearly carrying a flame for Morrison’s daughter—be involved in a plot to betray his country that Morrison tried to halt, and if so, can Trave stop it in time?

Chapter 1

Reinhard Heydrich, head of the Gestapo and the Sicherheitsdienst (SD), the intelligence division of the SS, stood to one side, a few yards away from the group of generals and admirals gathered around Adolf Hitler. An unfamiliar figure in his eyeglasses, the Führer was standing, looking down at a large map of Europe spread out across an enormous Teutonic oak table that had been moved for the purpose of the meeting into the centre of the main hall of the Berghof, Hitler’s summer residence high in the Bavarian Alps. One by one, the military leaders took turns to brief their commander in chief on the state of preparation for Operation Sea Lion, the high command’s code name for the invasion of England. It was due to be launched any day now according to timetables that had been agreed upon at previous conferences held during the summer either here or at the Reich Chancellery in Berlin.

The line of the sharp late summer sunlight coming in through the panoramic picture window at the back of the hall lit up the group around the table but left Heydrich a man apart, lurking in the shadows. He hadn’t been called on to speak yet, and he knew that this was unlikely to happen while the meeting remained concerned solely with issues of invasion strategy. He was here not as a soldier, but because it was his responsibility to plan and organise the control measures that would need to be taken against resistance groups and other undesirables once the panzer divisions had seized control of London, and he had already identified a suitably ruthless SS commander to take charge of the six Einsatzgruppen cleansing squads assigned to carry out the first wave of arrests and deportations. A special list of high-value targets assembled on Heydrich’s orders contained 2,820 names ranging from Winston Churchill to Noel Coward and H. G. Wells.

This was a military conference, so other than Heydrich and the Führer and Hermann Goering—here by virtue of his command of the Luftwaffe—there were no party men present. Heydrich’s thin upper lip curled in a characteristic expression of contempt as he watched the debate unfold. He hated these army and navy grandees bedecked in their medals and gold braid, and he sensed that the Führer did, too. They were careerists, men who had climbed the ladders of promotion in the interwar years, drawing their state-guaranteed pay at the end of every month, playing war games in their barracks, and toasting the kaiser, while true National Socialists like Heydrich had fought behind their Führer in the streets, prepared to die for the cause in which they all believed.

But there was another reason for Heydrich’s antipathy. Once upon a time, he too had been an officer with good prospects, an ensign on the battleship Schleswig-Holstein, until he had been summarily dismissed for conduct unbecoming an officer back in 1931. A woman he’d spurned when he’d met another he preferred had turned out to be a shipbuilder’s daughter who complained to her father, and Heydrich had paid the price. Admiral Raeder had taken away his honour with a stroke of a pen: the same Raeder who was now standing ten paces away from Heydrich, briefing Hitler on the naval preparations for the invasion. Every time he saw the admiral, Heydrich felt the injustice and humiliation flame up inside him again like a festering wound that would never heal. He fully intended to get even with Raeder, but not yet. The time wasn’t right. Heydrich was good at waiting. As the English said, vengeance was a dish best served cold.

Heydrich had no doubt that Raeder remembered. Not only that—he was sure that the admiral regretted his decision. It probably kept him up at night worrying. Everyone in this room knew Heydrich’s reputation. He’d observed the way they had all kept him at a distance when they first came in, throwing him uneasy sideways glances as they’d milled about the hall before the meeting began, drinking coffee from delicate eighteenth-century Dresden cups, until Hitler entered through a side door on the stroke of two o’clock and they all came to attention, raising their arms in salute.

Heydrich knew the names these men of power and influence called him behind his back—“blond beast”; “hangman”; “the man with the iron heart.” He knew how much they feared him, and with good reason. Back in Berlin, under lock and key at Gestapo headquarters, he had thick files on each and every one of them, recording every detail of their private lives in an ever-expanding archive of cross-referenced, colour-coded index cards that he had worked tirelessly to assemble over the previous nine years.

Some of them he’d even enticed into the high-class whore house he’d established on Giesebrechtstrasse with two-way mirrors and hidden microphones embedded in the walls. Within moments on any given day, he could summon to his desk photographs and sworn statements, letters, and even transcribed tape recordings of them spilling their sordid secrets to the girls he had had specially recruited for the task. Facts and falsehoods, truth and lies—it didn’t matter to Heydrich so long as the information could be of use in controlling people, forcing them by any means available to do his and the Führer’s will.

Heydrich smiled, thinking how one word from him in Hitler’s ear and the highest and mightiest of these strutting commanders in their glittering uniforms could find themselves down on their hands and knees, naked, manacled to a damp concrete wall in the cellar prison located in the basement underneath his office at 8 Prinz-Albrecht-Strasse. It amused him to have his victims cowering and screaming so close to where he worked, seated behind his magnificent nineteenth-century mahogany desk with an elaborately framed photograph of the Führer staring down at him from the oak-paneled wall opposite, ready to provide him with inspiration whenever he looked up from the stream of documents that required his constant attention every day.

From the outset, when he first joined the party back in 1931, Heydrich had felt a sense of kinship with Hitler that he had never experienced with anyone else he’d met before or since. And for several years now he had sensed that the Führer felt it too. Once, closeted together in the Führer’s apartment on the upper floor of the Reich Chancellery in Berlin, where Heydrich had gone to brief Hitler in the aftermath of the Kristallnacht pogrom two years earlier, the Führer had held up his hand for silence and looked Heydrich in the eye. It was only for a moment or two, but it felt to Heydrich as if he were back in the church at Halle where he had grown up, with the Catholic priest examining his soul. As a child he had turned away ashamed, but as a man he had met Hitler’s gaze and felt as though the Führer were looking inside him, turning him inside out, searching for the truth of who he really was. And then, after a moment or two, Hitler had nodded as if pleased with what he’d seen.

“We will go far together, you and I,” the Führer had said—Heydrich remembered his exact words—“because you are a true believer, and because, like me, you have the will. The will is everything, Reinhard. You know that, don’t you?”

Afterward they had carried on talking about roundups and press releases and other administrative measures against the vermin Jews, but the moment had stayed with Heydrich, vividly engraved on his memory as a life-changing moment. He admitted it to no one, but secretly he thought of himself as Hitler’s heir and the Third Reich, vast in size and purified in blood, as his own personal inheritance.

Nowadays he looked forward to meetings with Hitler almost like a lover awaiting his next tryst, and when he was in the Führer’s presence he watched him intently, as if he were storing up every impression of his master in the filing cabinet of his mind, packing each one carefully away for later scrutiny when he was alone, back in Berlin. There was a power, a certainty, in Hitler that drew Heydrich like a magnet. It always had, even in the early days when the National Socialist faithful had been so few, meeting in the back of smoke-filled beer cellars and conspiring together in the watches of the night, dreaming the impossible—Heydrich had known from the outset that Hitler was the one who could make the impossible come true.

But today the Führer seemed unlike himself for some reason. He was uncharacteristically silent, allowing the debate between the Wehrmacht commanders to carry on unchecked. Backward and forward, reproach and counter-reproach, the argument growing more heated by the minute. It was as if he were unsure of what to do, uncertain of his next move. To Heydrich it felt as if they were on a ship in a storm, keeling from side to side while the rudder stood unattended, crashing around with the buffeting of the waves.

“The weather conditions in the English Channel are extremely variable,” said Raeder mournfully. He sounded just like some miserable provincial schoolmaster reading from an instruction manual, thought Heydrich, and a Cassandra too—everything he said seemed negative, designed to undermine the invasion plan. “And we lack specialised landing craft,” Raeder continued. “Instead we are relying on converted river barges and ferryboats. Many of these are unpowered and can only be used in calm seas. They will make easy targets for the enemy. And there are also problems with transporting the heavy armour. We are working on making our tanks submersible, but we need more time. It is not the same as when we attacked Norway. We sustained heavy losses in that campaign, and this time the British know we are coming. They will use their navy against the beachheads even if we are able to establish them. And that is a big if—”

“I have said it before. The invasion front is too narrow,” interrupted Halder, chief of the army general staff, who had been shifting from one foot to another with growing impatience as Raeder talked. An old-school Prussian officer, he spoke in a clipped, angry voice, jabbing his finger down on the part of the map that showed the southeast coast of England. “One hundred miles is not enough even with paratroops landing in support. We might just as well put Army Group A through a sausage machine.”

“Yes, yes, I have heard this before,” said Hitler, showing undisguised irritation as he stepped back from the table. “More men; more armour; more boats. But it is air supremacy that we need— and before the autumn gales make a Channel crossing impossible. You promised me this,” he said, wheeling round to face Goering, who was standing on his right. “And yet the enemy is shooting down our planes every day, hunting down our bombers like dogs. Tell me the truth, Herr Reichsmarschall. No gloss; no varnish. Can you control the skies or not?”

Everyone turned to look at Goering. He was a natural focus of attention, as he was far and away the most distinctive figure in the room. His flamboyant uniform marked him out from everyone else, which was in fact just what he intended. Rumour had it that Goering changed his uniform five times a day, and his choice for this meeting was garish even by his usual standards. It was one of several bright white outfits that he’d designed for himself, replete with multicoloured crosses and decorations. Some of the larger medals he’d awarded to himself, and Heydrich knew from his army of spies that Goering’s appearance in this costume on cinema newsreels was an object of popular ridicule throughout the country, as no one could understand how he kept his uniforms so white when most of the population couldn’t get enough soap to keep their clothes even passably clean. Goering’s vanity was as boundless as his appetite, dwarfed only by his gargantuan self-belief.

“It is only a matter of time,” he said, standing with his arms akimbo, inflated with his own importance. “London is burning. The population is cowering in makeshift shelters . . . the docks are half-destroyed—”

“To hell with the docks,” Hitler interrupted angrily. “The skies are what matters. You heard my question. Can you break the English air force; can you destroy them like you promised?”

“Yes. Operation Eagle is succeeding,” said Goering, responding immediately in a quieter voice. His acute sensitivity to Hitler’s changing moods had stood him in good stead over the years, and he had gauged correctly that a measured assessment of the Luftwaffe’s capabilities, free of hyperbole, was what was now required. “It is a matter of simple mathematics,” he said. “Our attacks on British factories and airfields have massively reduced their capacity to keep pace with the severe losses that they are continuing to sustain every day. They are running out of planes and they are running out of pilots. Any day now their fighter command will have to withdraw from southern England and our landings can begin. Their weakness is shown by the damage we have already been able to inflict on London. They would never have allowed it if they could have prevented it.”

Hitler stared balefully at Goering for a moment, as if trying to assess whether his subordinate’s confidence was an act put on for his master’s benefit, but Goering met the Führer’s gaze full on without dropping his eyes.

“We shall see,” said Hitler, taking off his glasses. “We shall soon see if your assessment is correct, Herr Reichsmarschall.”

It was a signal that the conference was over. One by one, the military commanders saluted Hitler and left the hall. Heydrich moved to follow them, but Hitler held up his hand.

“Stay,” he said. “There is something I need to talk to you about. We can go out on the terrace. The fresh air will do us good.”

It was one of the last days of summer. The green-and-white umbrella canopies moved gently in the slight breeze above the white chairs and tables, and the bright afternoon sun threw shadows across the wide terrace and glittered in the windows of the Berghof. Across the tops of the pine trees down in the valley, the snow-capped mountains of Austria reared up under a cloudless blue sky. Who would have guessed, thought Heydrich, that hidden not far away from where they were standing, a battery of smoke-generating machines stood ready to drown the Berghof in a blanket of thick white fog should it come under threat from enemy bombers.

The war seemed very far away in the silence. The sound of his and Hitler’s footsteps echoed on the flagstones as they walked over toward the parapet.

“We can talk here,” said Hitler, sitting down at one of the tables and motioning Heydrich to the chair opposite. Hitler sighed, stretching out his legs, and then rubbed his knuckles in his eyes. Perhaps gazing at the map during the briefing had given him eye strain, or perhaps it was something more profound. What ever the cause, the Führer had certainly seemed out of sorts at the conference.

“I don’t like it,” said Hitler, shaking his head. He had his hands folded in his lap now, but he was gently clasping them together—a sure sign of inner turmoil. “This is not what I wanted. This is not the war we should be fighting.”

“Against England?”

“Yes,” said Hitler, bringing his hands together suddenly and holding them tight. His bright blue eyes were blazing with the intensity of his feeling. “They are not our enemy, and yet they will not listen to reason. It’s that fool Churchill. He has possessed them with his talk of blood and sacrifice. Don’t they understand that we have no quarrel with them? They can keep their empire. I want them to. It’s a noble institution. I have told them that again and again, but they will not listen.”

Hitler had begun to shout, but now he stopped suddenly. It was as though an electric motor had been suddenly turned off, and Heydrich tensed, waiting for the power to resume. But Hitler continued after a moment in a quiet voice, visibly holding himself in check.

“I don’t want this invasion. I am fully prepared to spend German blood to get this great country what it needs, but that is in the east,” he said, pointing with his forefinger out toward the mountains facing them across the valley. “We must defeat Bolshevism and take the land west of the Urals for our people. That is our destiny, but to lose an army trying to conquer Brighton or Worthing or Eastbourne . . . that is intolerable.

“Unerträglich!” Hitler spat out the word. It seemed once more as if rage were going to get the better of him, but again he pulled himself back from the brink. “The war in the west is a means to an end,” he said slowly, choosing his words carefully. “The object is to ensure that we are not stabbed in the back when we begin the war that matters, the one against Russia. And that must be soon, Reinhard . . . soon. We cannot wait much longer. Stalin is rearming; the Soviets are expanding—they are like ants; they come up out of the soil and multiply, and soon we will not be able to destroy them. Not if we wait.”

“Yes,” said Heydrich, inspired by the Führer’s vision. “As always, you are right.”

“And so we need peace with the English, not war,” Hitler went on after a moment. “But how do we achieve this? Not with an invasion. Not unless we have to, and even then I am reluctant. Raeder is an old woman, but he is right about the difficulties that we face with the crossing. You cannot rely on the weather. The Spanish tried three hundred and fifty years ago and their ships were wrecked. Napoleon could not even make it across the Channel. Our landing craft are second-rate and we don’t have the naval superiority we need to protect them.”

“But if we win in the air,” said Heydrich, “perhaps that will make the difference. The Reichsmarschall said that it is only a matter of time—”

“Time that we do not have,” said Hitler, interrupting. “I will believe Goering when the English air force stops bombing Germany. For now we need to try something else. And that is where you come in, Reinhard.”

Heydrich came alert. He’d been absorbed by the discussion of grand strategy and had forgotten for a moment that the Führer had had him wait behind after the conference for a purpose.

“What can I do?” he asked eagerly.

Hitler held a finger to his lips in a warning gesture. A pretty serving girl wearing a Bavarian peasant dress had appeared behind Heydrich with a tray of peppermint tea. She set the cups on the table and curtsied to the Führer, who smiled affably in response.

“Tell me about Agent D. Is he continuing to be reliable?” asked Hitler, sipping from his cup. He seemed serene now, and there was no trace of the anger and frustration that had been in evidence before the tea arrived. It was as if he were introducing a subject of minor interest into the conversation.

“Yes,” said Heydrich without hesitation. “He is one of the best agents I have ever had. I trust him implicitly.”

“Good. And his intelligence—is it useful?”

“He is doing well. As agreed, he provides disinformation where it cannot be detected as false and true intelligence where it does not threaten our security and can be verified by the enemy. His masters in the British Secret Service are pleased with him—he has recently been promoted to a level where he is present at some MI6 strategy meetings, and his reports are read by their Joint Intelligence Committee. Soon, if we are patient, he should have access to the most top-secret information.”

“Excellent,” said Hitler, rubbing his hands. “As always, your work does you credit, Reinhard. You make the Abwehr look like circus clowns.”

Heydrich bowed his head, savouring the compliment. There was nothing he would have liked better than to further extend his Gestapo empire into the field of foreign intelligence, where he was currently forced to compete not only with the Abwehr, the traditional Secret Service headed by Admiral Canaris, but with Ribbentrop’s equally second-rate Foreign Office outfit.

“But I am afraid that we are going to have to be a little less patient,” Hitler went on smoothly. “Agent D gives us an opportunity not just to make the British believe that we are serious about the invasion, but also to make them think that we can succeed. That is what is missing now. Churchill still thinks he can win. If he receives information that makes him stop believing that, then he will have to negotiate. He will have no choice. Do you understand me, Reinhard?”

“Yes, of course. But if they find out that what D is telling them is untrue, then his cover will be blown. He is an important asset—”

“And will remain so,” said Hitler, holding up his hand to forestall further objection. “If D’s cover is blown, then Churchill won’t believe the information he’s being given and our scheme fails. No, we must exaggerate our strength on the sea and in the air, but not to the point where it strains credibility. It’s a delicate balance—a task requiring a sure hand. Can I rely on you, Reinhard? Can you do this for me?”

“Yes. I am a tool in your hand. You know that. But I will need authority to obtain details of our capability from the service chiefs and advice on the level to which it can be distorted without arousing suspicion.”

“Here. This should be sufficient,” said Hitler, taking a folded document from his pocket and handing it across the table. “Now, tell me about D’s source for his information. What do the British believe the source’s position is at present?”

“On the general staff, attached to General Halder.”

“I see,” said Hitler, licking his lips meditatively. “Well, I think we are going to have to award him an increase in status if the British are going to believe that he’s able to provide D with information of the value that I have in mind. What do you suggest, Reinhard?”

“Aide-de-camp?”

“Yes, very good—that sounds just right,” said Hitler, looking pleased. “Sufficient status to give him access to top-level military conferences like the one today, and to make it credible that he’s heard me speak of both my willingness to invade and my desire for peace. We can downgrade the source’s status later if it becomes too conspicuous for a fictional character,” Hitler added with a smile.

“All as you say—it will be done,” said Heydrich, getting up from the table and putting on his SS cap, which he had held balanced on his knees during the conversation. He was about to salute, but Hitler forestalled him.

“Remind me—what is your usual method for communicating with D?” he asked.

“We have a reliable contact in the Portuguese embassy in London. Information and reports are sent through the diplomatic bag to Lisbon and then brought on to Berlin from there, and the same in the other direction. It takes time, but it is safe and efficient.”

“And radio?”

“The codes we have work for short messages. But not for anything longer—D does not have an Enigma machine and so a report or a briefing instruction like this one wouldn’t be secure. There is a drop we can use that D knows about.”

“A drop?”

“Yes. On the coast of Norfolk, northeast of London. We have a sleeper agent there who will pick up documents that we drop from a plane. It works. I have used it before, but D would have to go there to collect.”

“Very well. Use the drop. Time is of the essence. Everyone needs to understand that. If we wait too long, the weather will turn against us and Churchill will know we are not coming. So you must give this task top priority—put aside everything else that you are working on until the briefing document is ready for me to look at. And when it is, bring it here in person, and then, if I approve, you can send it.”

Hitler nodded and Heydrich raised his right arm in salute and turned away. At the top of the steps leading down to the road, he looked back at the Führer, who was now leaning back in his chair with his hat tipped down over his eyes and his legs stretched out in front of him. He looked like a holidaymaker, Heydrich thought, enjoying the last of the day’s sunshine with a cup of afternoon tea at his side. A neutral observer would have laughed at the suggestion that this was the most powerful man in Europe, who held the fate of nations balanced in the palm of his hand.

Chapter Two

A flight of geese rose up in a sudden rush from the island in the lake, beat the air above the ruined bird keeper’s cottage, and then soared into the London sky toward the white vapour trails of the fighter aircraft that had been engaged in aerial battles above the City for most of the day.

Seaforth stopped to look, but Thorn paid no attention, continuing his angry march down Birdcage Walk with his hands thrust deep inside his trouser pockets. Ever since he first came to London, Seaforth had loved St. James’s Park, and he felt profoundly grateful that he now worked so close to it that he could come here almost every day, sit under the ancient horse-chestnut trees, and look up past the falling boughs of the weeping willows to where the buildings of Whitehall rose from out of the water like the palaces of a fairy kingdom. But today there was no time to dawdle. Churchill was waiting for them in his bunker, and Seaforth turned away from the view and walked quickly to catch up with his companion.

He felt intensely alive. In the morning and again in the afternoon, he’d left his desk and gone out and joined the crowds in the street outside, gazing up at the aerial dogfights going on above their heads—Hurricanes and Spitfires and Messerschmitts wheeling and twisting through crisscrossing vapour trails, searching for angles of attack. The noise had been tremendous—the roar of the machine guns mixed up with the exploding anti-aircraft shells; the underlying drone of the aeroplanes; the shrapnel falling like pattering rain on the ground; bombs exploding. Several times he’d watched transfixed as planes caught fire and tumbled from the sky, with black smoke pouring out behind them as they fell. A Dornier bomber had hit the ground a few streets away, exploding in a column of crimson-and-yellow flame, and Seaforth could still hear the people around him cheering, throwing their hats up into the air while the German crew burned. Some bombs had fallen close by—there was a rumour that Buckingham Palace had been hit—but Seaforth had been too absorbed in the battle to worry about his personal safety. He’d felt he was watching history unfold fight above his head.

And then at the end of the day he had been caught up in the drama when the unexpected summons had come from the prime minister’s office and he and Thorn had set off together through the park. Now the day’s fighting seemed to be over—there was no more sign of the enemy, only a few British fighters patrolling overhead, although Seaforth knew that the bombers would almost certainly return after dark to rain down more terror on the city’s population. Seaforth wondered about the outcome of the day’s battle. He’d tried to talk to Thorn about it, but Thorn had shown no interest in conversation.

Seaforth didn’t like Thorn; he didn’t like him at all. He objected to the disdainful, upper-class voice in which Thorn spoke to him, treating him like a member of some inferior species. He rebelled against having to answer to a man for whom he had no respect. He tipped his felt hat back at a rakish angle and amused himself with trying to annoy Thorn into talking to him.

“Is it true what they say, that Churchill receives visitors in his bath?” he asked. “I hope he doesn’t do that with us. I think I’d find it hard to concentrate. Wouldn’t you?”

Thorn grunted and stopped to light a cigarette, cupping the lighted match in his hand to protect it from the wind.

“You hear so many strange things,” Seaforth went on, undaunted by his companion’s lack of response. “Like how he takes so many risks, going up on the roof of Downing Street to watch the bombs and the dogfights—as if he’s convinced that nothing will ever happen to him, like he’s got some kind of divine protection; a contract with the Almighty.”

“Why are you so interested in where he goes?”Thorn asked sharply.

“I’m not. I’m just trying to make conversation,” said Seaforth amicably.

“Well, don’t.”

“What ever you say, old man,” said Seaforth, shrugging. He whistled a few bars of a patriotic song and then went back on the attack, taking a perverse pleasure in Thorn’s growing irritation.

“How many times have you seen the PM? Before now, I mean?” he asked.

“Two or three. I don’t know,” said Thorn. “Does it matter?”

“I’m just trying to get an idea of what to expect, that’s all. Where did you go—to Number 10 or this underground place?”

“You ask too many damn questions,” said Thorn, putting an end to the conversation. He took a long drag on his cigarette, inhaling the smoke deep into his lungs. He was trying not to think about Seaforth or the forthcoming interview with the prime minister, and the effort was making his head ache.

He was eaten up with a mass of competing thoughts and emotions, and he felt too tired to work out where genuine distrust of Seaforth ended and his own selfish resentment of the young upstart began. Churchill’s summons to the two of them had placed him in an impossible position. His inclusion was recognition that he was the one in charge of German intelligence, but Thorn knew perfectly well that it was Seaforth Churchill wanted to talk to. It was Seaforth’s report that the prime minister wanted to discuss; it was Seaforth’s high-value agent in Germany he was interested in. Thorn was no better than a redundant extra at their meeting.

They reached Horse Guards and climbed the steps to 2 Storey’s Gate. Thorn felt a renewed surge of irritation as he sensed Seaforth’s growing excitement. They showed their special day passes to a blue-uniformed Royal Marine standing with a fixed bayonet at the entrance and went down the steep spiral staircase leading to the bunker. Through a great iron door and past several more sentries, they came to a corridor leading into the labyrinth. Seaforth blinked in the bright artificial light and greedily took in his surroundings—whitewashed brick walls and big red steel girders supporting the ceilings. It was like being inside the bowels of a ship, Seaforth thought. The air was stale, almost fetid, despite the continuous hum of the ubiquitous ventilation fans pumping in filtered air from outside, and there was an atmosphere of concentrated activity all around them. Through the open doors of the rooms that they passed, Seaforth saw secretaries typing and men talking animatedly into telephones—some in uniform, some in suits. People hurried by in both directions, and Seaforth was struck by the paleness of their faces, caused no doubt by a prolonged deprivation of light and fresh air. Tellingly, a notice on the wall described the day’s weather conditions, as if this were the only way the inhabitants of this godforsaken underworld would ever know whether the sun was shining or rain was falling in the world above.

They stopped outside the open door of the Map Room. This was the nerve centre of the bunker, where information about the war was continually being received, collated, and distributed. Two parallel lines of desks ran down the centre of the room, divided from each other by a bank of different-coloured telephones—green, white, ivory, and red—the so-called beauty chorus. They didn’t ring but instead flashed continuously, answered by officers in uniform sitting at the desks. Over on a blackboard in the corner, the day’s “score” was marked up in chalk—Luftwaffe on the left with fifty-three down and RAF on the right with twenty-two. It was a significant number of “kills” but fewer than Seaforth had anticipated, judging from the mayhem he’d witnessed in the skies over London during the day.

Seaforth’s eyes watered. The thick fug of cigarette smoke blown about by the electric fans on the wall made him feel sick, but he swallowed the bile rising in his throat, determined to see everything and to try to understand everything he saw. No detail escaped his notice—the codebooks and documents littering the desks lit up by the green reading lamps; the map of the Atlantic on the far wall with different-coloured pins showing the up-to-date location of the convoys crossing to and from America; the stand of locked-up Lee-Enfield rifles just inside the entrance to the room.

“What are you looking at?” asked a hostile voice close to his ear. It was Thorn. Seaforth had been so absorbed in his observation of the Map Room that he had momentarily forgotten his companion. But Thorn had clearly not forgotten him. He was staring at Seaforth, his eyes alive with suspicion.

“Everything,” said Seaforth. “This is the heart of the operation. Of course I’m curious.”

“Curiosity killed the cat,” said Thorn acidly.

“Mr. Thorn, Mr. Seaforth. If I could just see your passes?” A man in a dark suit had appeared as if from nowhere. “Good. Thank you. If you’d like to come this way. The prime minister will see you now.”

They passed through an anteroom, turned to their left, and suddenly found themselves in the presence of Winston Churchill, dressed not in a bathrobe but in an expensive double-breasted pinstripe suit with a gold watch chain stretched across his capacious stomach. He was wearing his trademark polka-dot bow tie and a spotless white handkerchief folded into a precise triangle in his top pocket. It was the Churchill that was familiar from countless Pathé newsreels and photographs except for the stovepipe hat, and that was hanging on a stand in the corner. Without the hat he seemed older—the wispy strands of hair on his head and the pudginess of his face made him seem more a vulnerable, careworn old man than the indomitable British bulldog of popular imagination.

He got up from behind his kneehole desk just as they came in, depositing a half-smoked Havana cigar in a large ashtray that contained the butts of two more.

“Hullo, Alec,” he said, shaking Thorn’s hand. “Good of you to come—sorry about the short notice. And this must be the resourceful Mr. Seaforth,” he went on, fixing a look of penetrating inquiry on Thorn’s companion, who had hung back as they’d entered the room, as if overcome by an uncharacteristic shyness now that he was about to meet the most famous Englishman of his generation.

Eagerness and then timidity: Thorn was puzzled by the sudden change in Seaforth, who seemed momentarily reluctant to go forward and shake Churchill’s outstretched hand. And then, when he did so, Thorn could have sworn that Seaforth grimaced as if in revulsion at the physical contact. But Churchill didn’t seem to notice, and Thorn realised that it could well be the cigar smoke that was causing Seaforth discomfort. He was well aware how much Seaforth hated tobacco, and the sight of his subordinate’s nauseated expression had been the only redeeming feature for Thorn of Seaforth’s recent inclusion at strategy meetings in the smoke-filled conference room back at HQ.

“I don’t need you, Thompson,” said Churchill. For a moment, Thorn had no idea whom the prime minister was talking to, until he turned to his right and realised that another man was present in the room. It was Walter Thompson, Churchill’s personal bodyguard, sitting like a waxwork in the corner, tall and ramrod straight. Without a word, Thompson went out and closed the door behind him.

“Drink?” asked Churchill, crossing to a side table and mixing himself a generous whisky and soda. “By God, I need one. I hate being down here with the rest of the trogs, but Thompson and the rest of them insist on it when the bombing gets bad, so I don’t suppose I’ve got too much choice. I’d much prefer to have been up topside watching the battle. Seems like Goering’s thrown everything he’s got at us today, but the brass tell me we’ve weathered the storm so far, at least. You know, I don’t think I’ve been as proud of anyone as I’ve been of our pilots these last few weeks. Tested in the fiery furnace day after day, night after night, and each time they come out ready for action. Extraordinary!”

Churchill looked up, holding out the whisky bottle. Thorn accepted the offer, but Seaforth declined.

“Not a teetotaler, are you?” asked Churchill, eyeing Seaforth with a look of distrust.

“No, sir,” said Seaforth. “I just want to have all my wits about me, that’s all. I’m expecting some difficult questions.”

“Are you now?” said Churchill, raising his eyebrows quizzically as he resumed his seat and waved his visitors to chairs on the other side of the desk. “Well, it was certainly an interesting report you sent in,” he observed, putting on his round-rimmed black reading glasses and examining a document that he’d extracted from a buff-coloured box perched precariously on the corner of the desk. “Lots of nuts-and-bolts information, which I like, but most of it saying how well prepared Herr Hitler is for his cross-Channel excursion, which I like rather less. We knew about the heavy buildup of artillery and troops in the Pas-de-Calais, of course, but the number of tanks they’ve converted to amphibious use is an unpleasant surprise, and we’d assumed up to now that most of their landing craft was going to be unpowered.”

“They’ve installed BMW aircraft engines on the barges,” said Seaforth. “They seem to work, apparently.”

“So I see. Five hundred tanks converted to amphibious use,” said Churchill, reading from the document. “It’s a large number if they can get them across, but that’ll depend on the weather, of course, and who’s in control of the air, and we seem to be holding our own in that department, at least for now, at any rate.”

“There are the figures for Luftwaffe air production in the report as well—on the last page,” said Seaforth, leaning forward, pointing with his finger.

“Yes,” said Churchill. “Again far higher than we expected. But to be taken with a pinch of salt, I think. Goering would be likely to exaggerate the numbers for his master’s benefit.” He put down the report, looking at Seaforth over the tops of his glasses as if trying to get the mea sure of him. “Your agent’s report is basically a summary of what was discussed at the last Berghof conference, with a few opinions of his own thrown in for good measure. Is that a fair description, Mr. Seaforth?”

“He’s verified the facts where he can,” said Seaforth.

“But he’s an army man working for General Halder, who’s another army man,” said Churchill. “He’s not going to have inside information about the Luftwaffe.”

“He knows one hell of a lot for an ADC, and a recently promoted one at that,” Thorn observed sourly. It was his first intervention in the conversation.

“Too good to be true? Is that what you’re saying, Alec?” asked Churchill, looking at Thorn with interest.

“Too right I am. The source material was nothing like this before. Now it’s the Führer this, the Führer that. It’s like we’re sitting round a table with Hitler, listening to him tell us about his war aims.”

“My agent didn’t have access before to Führer conferences,” Seaforth said obdurately. “Now he does.”

“Why’s he helping us?” asked Churchill. “Tell me that.”

“Because he hates Hitler,” said Seaforth. “A lot of the general staff do. And he has Jewish relatives—he’s angry about what’s happening over there.”

“How well do you know this agent of yours?”

“I recruited him personally when I was in Berlin before the war. He felt the same way then—he loved his country but hated where it was going. I have complete confidence in him.”

“As do his superiors, judging from his recent promotion,” observed Churchill caustically. He was silent for a moment, scratching his chin, looking long and hard at the two intelligence officers as if he were about to make a wager and were considering which one of them to place his money on. “Betrayal is something I’ve always found hard to understand—even when it’s an act committed for the best of motives,” he said finally. “It’s outside my field of expertise. But we certainly cannot afford to look a gift horse in the mouth, even if we do choose to regard the animal with some healthy scepticism. So, let us assume for a moment that what your agent says is true and that Hitler is ready and determined to come and pay us a visit once he’s got all his forces assembled—”

“He thinks Hitler doesn’t want to,” said Seaforth, interrupting.

“Thinks!” Thorn repeated scornfully.

“Hitler said as much at the conference,” said Seaforth, leaning forward eagerly. “He wants to negotiate—”

“A generous peace based broadly on the status quo,” said Churchill, finishing Seaforth’s sentence by quoting verbatim from the report. “And that may well be exactly what he does want,” he observed equably, picking up his smouldering cigar and leaning back in his chair. “The Führer thinks he is very cunning, but at bottom the way his mind works is very simple. He’s a racist—he wants to fight Slavs, not Anglo-Saxons. But the point is it doesn’t matter what he wants. We cannot negotiate with the Nazis however many Messerschmitts and submersible tanks they may have lined up against us. Do you remember what I called them when I became prime minister four months ago—‘a monstrous tyranny, never surpassed in the dark, lamentable catalogue of human crime’?” Churchill had the gift of an actor—his voice changed, becoming grave and solemn as he recited the line from his speech. But then he smiled, taking another draw on his cigar. “Grand words, I know, but the truth. We must defeat Hitler or die in the attempt. There is no hope for any of us otherwise. And so the strength of his invasion force and his wish for peace cannot change our course.”

Abruptly the prime minister got to his feet. Thorn nodded his approval of Churchill’s policy, but Seaforth looked as though he had more to say. He opened his mouth to speak, then changed his mind.

“Thank you, gentlemen. Reports like this one are invaluable,” said Churchill, tapping the document on his desk. “If you get more intelligence like this, I shall want to see you again straightaway. Both of you, mind you—I like to hear both points of view. And you can call my private secretary to set up the appointment so we don’t have delays going through the Joint Intelligence Committee—he’ll give you the number outside. My predecessors made a serious mistake in my opinion keeping the Secret Service at arm’s length. It takes a war, I suppose, to inject some sense into government.

“Good-bye, Alec. Good-bye, Mr. Seaforth,” he said affably, shaking their hands across the desk. “Seaforth—an interesting name and not one I’ve heard before,” he said pensively. “Sounds a bit like Steerforth—the seducer of that poor girl in David Copperfield. Came to a bad end, as I recall. A great writer, Dickens, but inclined to be sentimental, which is something we can’t afford to be at present. The stakes are too high; much too high for that.”

Copyright © 2012 Simon Tolkien

With the publication of The Inheritance, Simon Tolkien was lauded as a naturally gifted storyteller who possesses a terrific command of language and a unique perception into the darker sides of human nature. In Orders from Berlin, Simon takes readers back to the case that started it all for Trave, the hero of his last two critically acclaimed novels.