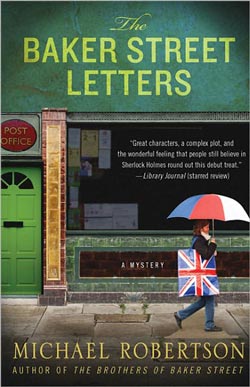

[Like the excerpt? Enter to win both this book and the sequel!]

In Los Angeles, a geological surveyor maps out a proposed subway route—and then goes missing. His eight-year-old daughter in her desperation turns to the one person she thinks might help—she writes a letter to Sherlock Holmes.

That letter creates an uproar at 221b Baker Street, which now houses the law offices of attorney and man-about-town Reggie Heath and his hapless brother Nigel. Instead of filing the letter as he’s supposed to, Nigel decides to investigate. Soon he’s flying off to L.A., inconsiderately leaving a very dead body on the floor in his office. Big brother Reggie follows Nigel to California, as does Reggie’s sometime lover, Laura—a quick-witted stage actress who’s captured the hearts of both brothers.

When Nigel is arrested, Reggie must use all his wits to solve a case that Sherlock Holmes would have savored, and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle fans will adore.

Prologue

Los Angeles, 1997

He only wanted just one cigarette.

He knew he shouldn’t, and not just because both of his ex-wives used to say so or because his doctor still said so.

He knew he shouldn’t because the company rules for sandhogs on the new subway dig said so.

But the rules hadn’t been pulling twelve-hour shifts.

And the hot permits for acetylene torches had already been granted, so he knew there wasn’t any flammable gas.

And he really only needed just one.

So he moved farther into the tunnel, beyond the shining fresh concrete, away from the flammable plastic liners, and out of sight of the foreman. He sat on a muck hauler to take his break, and he took out just one cigarette and put it between his lips.

And then he lit a match.

Chapter 1

London, six weeks later

“Why are you staring at me that way?”

Laura hardly looked up from her dinner to ask this. She arched one eyebrow over one olive green eye.

“Your hair,” lied Reggie, “is in your champagne.”

She laughed, and Reggie hoped it was because she remembered a September picnic in Kensington Gardens, when her red hair had indeed been in the champagne, and pretty much everywhere else.

He wanted her to think of that, because tonight, with moonlight streaming into his Butler’s Wharf penthouse, he was beginning to fear that she did not intend to let it down at all.

Nor had she the week before. And so Reggie had begun to stare.

But now there was a noise from the kitchen, and Mrs. Hampstead—who should have been getting ready to bring out Blackwell tarts—brought the phone instead.

“It’s your brother,” she said.

“I’ll return it in the morning.”

“Your brother!” Mrs. Hampstead said emphatically, thrusting the phone again between Reggie and Laura. “He says it is urgent.”

“Tell him I’ll call him back,” repeated Reggie. “In the morning.”

“Suit yourself. Just as though he’s not the only brother you’ve got.”

Mrs. Hampstead had an uncanny knack for spouting phrases that Reggie used to hear from his mother.

“Quite right, Mrs. Hampstead,” said Laura. “Reggie, there’s no use in being stubborn.”

Reggie looked across and tried to read Laura’s expression, but she did not meet his gaze.

He accepted the phone and spoke brusquely.

“What is it, Nigel?”

“I can’t explain it over the phone,” said Nigel. “You’ll have to see it for yourself.”

The concern in his younger brother’s voice was evident, but to Reggie that was not proof of a crisis. At thirty-three, Nigel was just two years younger than Reggie—but the brothers did not always rate the crises of life on the same scale.

“I’m sure it can wait—,” began Reggie.

Laura looked up from her plate. “It’s all right,” she said, and she glanced at her watch as she said it. “I should be going anyway.”

Reggie tried quickly to see her eyes, but she looked away again.

“I’ll be along shortly,” he said, annoyed, into the phone.

Laura gathered a cream-colored wrap around bare, freckled shoulders, and they took the exterior lift down from the penthouse.

They walked from the shining metal-and-glass lift onto the wharf and then got in Reggie’s XJS.

For a long moment, as they drove along the Embankment, with the damp air and river scents being stirred up by a light rain, neither of them spoke.

Then Laura said, “You shouldn’t be so sharp with your brother.”

“Was I sharp?”

“Yes. And he only got out a month ago.”

“I’m aware of that,” said Reggie, and he was, though he was tired of having to think about it. “My mind was on something else,” he said.

“I’m tired tonight anyway,” Laura replied, and then added, “I’m sure it will be late when you’re through.”

Reggie thought she said this as though she were relying on it. This was worrisome. He said, “I was just beginning to think I’d found him a position he couldn’t bollix up. And this was only because his predecessor came back from holiday in America and stepped in front of a double-decker. You can’t count on breaks like that for all your positions.” Reggie realized he was speaking sharply again, and he fell silent.

“The poor man,” said Laura, and Reggie, to his astonishment, realized that he was becoming jealous now even of her sympathy. Sympathy for a stranger, for that matter. For a dead stranger, in fact.

“Must have forgotten which way the traffic moves,” added Laura.

“Mashed like a potato,” Reggie said tightly.

He turned right onto a narrow Chelsea street and then into the drive for Laura’s ivy-covered brick mews.

They walked on damp flagstones through the front courtyard. Then Laura stood in the doorway, kissed Reggie once lightly, and said good night. He wondered just what alternative plans she might have for the remainder of the evening—but he managed not to ask.

He got in his car and drove around the eastern perimeter of Hyde Park toward Marylebone. He continued almost to Regents Park and then turned south onto Baker Street.

He drove half a block and then parked. He was now at Dorset House—a structure that headquartered the Dorset National Building Society and that made up the entire Two Hundred block of Baker Street.

It was late as Reggie entered the building, and the lobby was deserted except for a security guard, who nodded as Reggie passed by.

Reggie crossed to the lifts, his footsteps echoing on the marble floor.

He had just recently leased the next floor above for his new law chambers. The location was uncommonly far from the Inns of Court—few barristers in London had chambers beyond easy walking distance of the Inns and their clubbiness—but Reggie was willing to break that convention. And the lease from Dorset National was at a very decent bargain. Such a good deal, in fact, that at first he had been suspicious—but he was beginning to accept it now as just good fortune.

He took the lift up one floor and stepped out—almost knocking down Ms. Brinks, who was trying to step in.

“Oh,” she said. “So sorry, I wasn’t expecting—”

“I wasn’t either,” said Reggie. “Just on your way out?”

“Yes,” she said. “But since you’re here…”

“Yes?”

Reggie waited as his very efficient secretary—she had many years on the job and was often happy to say so—sorted quickly through the stack of papers in her arms.

“Perhaps you’d like to sign these?” she said. “Your broker at Lloyd’s sent them over. I wanted to have them ready for you Monday morning, but here you are now. He’s uneasy about your presence in the construction trades, and thought you might prefer to underwrite something at lower risk.”

“Such as?”

“A media conglomerate, I believe he said. Entertainment and such.”

Reggie took the papers and began to look them over. Ms. Brinks—fiftyish, thin as a rail, and hyperactive by nature—waited impatiently.

“He says it’s a low rate of return, but lower risk,” she continued. “After all, who ever filed a claim over a flick?”

“Yes,” said Reggie, signing the forms and giving them back. “Thank you, Ms. Brinks. My brother still in?”

“Yes, I think so.”

“Good night, then.”

“Good night.”

Ms. Brinks took the lift, and Reggie continued on his way down the corridor, between shoulder-high gray cubicle partitions. The cubicles were dark and mostly empty—they were left over from Dorset National’s previous operations there, and Reggie’s chambers wasn’t large enough to make use of them. Not yet.

At this hour, the main lamps were off. But there was residual light coming through the windows on the Baker Street side, intermittent glimmers from the senior clerk’s PC at the opposite side, and, at the end of the corridor, the light escaping through the blinds and doorway of Nigel’s office.

The air-conditioning was off as well. The temperature was tolerable, but the air was nevertheless stifling, the lack of circulation allowing scents of printer toner and old paper to accumulate.

He hoped this wouldn’t take long.

The door to Nigel’s office was half-open. Reggie stopped in the doorway and took a moment to note whether Nigel’s working habits had improved.

They had not.

Crumpled balls of paper and confection wrappers littered the floor around the wastebasket in the near corner, where Nigel had attempted bank shots and missed. On his desk, a package of sweet biscuits spilled crumbs onto a stained blotter. And the incoming-letter basket fairly overflowed with correspondence that Nigel had yet to act upon.

Next to the incoming basket, beneath a scattered handful of chocolate Smarties, was an opened letter addressed to Nigel from the Law Society.

That had to be the reason he had called.

Nigel was doing something with the drawers of a tall wooden filing cabinet, his back toward the door. Reggie rapped his knuckles on the door frame. Nigel swiveled his desk chair to face Reggie, in the process mangling half a dozen blank forms that had slipped to the floor.

“Oh,” Nigel said almost immediately. “You were with Laura.”

“And you realize that just now because…?”

“That perplexed look you’ve had of late.”

Reggie didn’t want to talk about it. “Is it the disciplinary tribunal?” he asked, pointing at the Law Society letter.

“That? Oh, yes.”

“Well?”

“Well what?”

“What does it say? Have they scheduled your reinstatement hearing?”

“Yes. The tribunal convenes Monday morning.”

“Excellent. It’s about time you wound that up. You can drop all this clerical stuff and get back to what suits you.”

“Of course,” said Nigel, with no particular emphasis.

“Did they say anything about the substance of the charge?”

“Apparently they feel I’ve done my penance; they’re no longer threatening to revoke my solicitor’s license permanently.”

“As expected. They’ve been sensitive to this ‘inappropriate conduct’ stuff ever since that lawyer in Staffordshire made page one of the Daily Mail by shagging a client’s wife. He probably shouldn’t have, given the client was in the House of Lords. But your hearing should be just a formality. You’ll make nice, and I’ll sit at the table to show support. No doubt at all you’ll be reinstated.”

Nigel listened to all that without objection—though he had begun to drum his fingers, and one knee jittered slightly. “I’m sure it will all be fine,” he said now. “But, as to the reason I called—”

“It wasn’t this?”

“Of course not,” said Nigel, and he attacked the mess on his desk, shoving aside the tube of Smarties and the sweet biscuit crumbs. He opened the folder he had just taken from the file cabinet, and he began to push letters from it onto the blotter. Then he stopped.

“Perhaps I shouldn’t have phoned. You won’t understand this.”

“You mean I won’t agree,” Reggie said suspiciously.

“No, you would agree if you understood. But you won’t understand.”

“Nigel, Laura is waiting. Will you tell me what is wrong?”

Nigel separated the letters and displayed them on the desk in front of Reggie.

“Part of my job is to reply to correspondence that should have been delivered elsewhere—or rather, not at all.”

“What’s the problem? If it’s misdelivered, send it back.”

“I can’t. It’s in the lease.”

“What is?”

“That the tenant receive these letters, and not complain to the postmaster to get them stopped, but instead respond to them—with these bloody forms I have around here someplace.”

“I still don’t know what you’re talking about.”

“The in-basket is full of them. Just take one off the top.”

Reggie did so. He began to read one letter—and then he stopped abruptly. He stared at the name of the addressee for a moment, and he gave his brother an incredulous look.

“Nigel, is this a joke?”

“It’s not a joke.”

Reggie read aloud the address on the envelope: “Mr. Sherlock Holmes, 221b Baker Street, London.”

He tossed the letter dismissively back onto the desk in front of Nigel.

Nigel was unfazed. “Look at the others,” he said.

Reggie picked up another letter and read the address: “Sherlock Holmes, Consulting Detective, 221b Baker Street.”

And another: “Mr. Sherlock Holmes, Bee Keeper, c/o 221b Baker Street.”

Nigel nodded and folded his arms as though he’d made his point.

“Are you telling me everything in this basket is addressed to him?” demanded Reggie.

“Yes—they’re pretty much all like that, although most aren’t so much interested in the beekeeping aspect.”

Reggie stared at the letters in his hand and then back at Nigel again.

“You mean simply because our address is—”

“Yes,” said Nigel. “Simply because you’ve located your new chambers in a building that takes up the entire Two Hundred block of Baker Street.”

“But surely no one could actually believe—”

“Apparently some would do.”

Reggie looked again at the letters that had piled up in the basket. There were dozens of them, in all kinds of formats—scrawled in longhand and typed on ancient Remingtons; laser-printed and hand-lettered on lined yellow pads.

In fact, the letters to Sherlock Holmes outnumbered all the legitimate correspondence. This was annoying.

“Doesn’t it occur to these people that if he were real, he’d be long dead and rotten?”

Nigel shrugged. “What can I tell you? Dorset House has been getting and responding to the letters for years. The Baker Street Tourist Board loves them for it.”

“Then let them handle the responses. Why should we worry about—”

“Because the letters have always been delivered to this floor of this building— and now you’ve taken a leasehold on it. And as you know, the lease specifically says that the occupant of these premises takes responsibility for the letters.”

Reggie said nothing for a moment, and now it was Nigel’s turn to give his older brother an incredulous stare.

“You did know this, of course,” said Nigel. “I mean, you did read the full lease agreement before signing?”

“Of course,” said Reggie.

“Article 3d, paragraph 2a, of addendum G?”

Reggie was silent. He knew what had happened, though he was loath to admit it—especially to Nigel. The lease terms had been too favorable—and he had been too eager.

He sighed and sat down. “It just seemed so damn inconsequential at the time,” he said.

“It’s true that most of the letters are trivial,” said Nigel. “A surprising number of cat owners seem to believe he must be not only real and alive but also eager to come out of retirement to track down a stray tabby that is just out having the time of its life anyway. But—”

“My mistake,” Reggie interrupted. “I’ll get it stricken from the lease in the next go-round. And in the meantime, I’ll speak to Ocher— handling these bloody things can be assigned to someone else. You should have more responsible tasks.” He stood and picked up his overcoat.

“But that’s not the problem,” said Nigel.

“What, then?” Reggie stopped in the doorway.

“It’s these,” said Nigel, holding up three letters. “All of them, ostensibly, from the same person. This one came this morning. It references another that was in the file from a month back. But both of them refer to yet another, which I finally tracked down, filed out of order in the archive drawer. And that one—the original letter from the archives—was received here nearly twenty years ago.”

“And that creates a problem because…?”

“See for yourself.”

Reggie picked up the archived letter and read it quickly. It was handwritten and a bit faded—but quite legible, with a return address in Los Angeles.

“She’s looking for her father. He disappeared shortly before Christmas. She wants help in finding him. She encloses something she calls ‘Daddy’s maps’ to assist in that search.” Reggie stopped reading. “To find the father who abandoned her, she’s writing to a character of fiction.”

“Yes.”

“It’s touching. Or pathetic. But—”

“Pathetic, perhaps,” said Nigel, “if she wrote that letter as an adult. I would guess she was no more than eight years of age at the time, from the obvious pride and care she took in her cursives.”

“That and the fact that she appears to have signed in wax crayon.”

“Yes. Now look at the other two.”

Reggie glanced at the next two letters. There was no crayon now; both were laser-printed and signed in ink. “She asks if we still have the enclosures sent in her original letter, and that we kindly return them if we have them. Then she asks the same question again, a bit more insistently.” He put the letters on the desk.

“Do you see the problem?” asked Nigel.

“I suppose,” said Reggie. “But it’s no great crisis. Return the enclosures if you can dredge them up; if not, send the standard form with apologies.”

“You’re missing the point,” said Nigel. “She didn’t write the recent letters. She wrote only the first one, as a child. These last two are written in her name, but they are clearly forgeries.”

Reggie sighed. “I blame myself,” he began. “I should have found you a position that was a little less—”

“If you’ll only look!” said Nigel, standing and leaning precariously across the desk to display the letters just inches from Reggie’s face. “The signatures are all wrong. They’re careful and deliberate and perfect, exactly like the others except for the crayon. But no adult continues to sign exactly as they did as a child. It cannot be her signature, and Mara did not write these!”

“Mara?” said Reggie.

Nigel turned red and inched back into his chair. “That is her name,” he said.

Reggie could only stare and try to discern if Nigel’s mental state was real cause for concern—or if he was just on another annoying but nonlethal tear, which would occupy his interest for a few days but do no harm other than distracting him from more ordinary or more responsible activities.

“Nigel,” Reggie said carefully, “surely you have not contacted this young woman?”

“No,” Nigel said flatly. “I couldn’t reach her. I left a message on her machine.”

“Are you out of your bloody mind?” said Reggie. “Your legal career is on the line, and you’re mucking about with people who write to a character of fiction as if he—we—our address—were some sort of general help center!”

“No one is doing any mucking here. I only—”

“Nigel, this is a law chambers.”

“In this one very specific instance, I think—”

“Never mind my chambers’ reputation, just think for a moment of the lawsuits you could inspire by encouraging some mental eight-year-old to think that Sherlock Holmes actually exists.”

“She’s not a mental eight-year-old; she’s an actual one. I mean she was. She’s not now, of course.”

“The Law Society will see a pattern here—you meddling again where you don’t belong. Under the circumstances, that should be the last thing you want.”

“I said you would not understand,” Nigel said in an exasperated tone. “But at least look at the enclosures.” He held out an aged clasp envelope, raggedly torn across the top corners. “There’s something here that—”

“No—I bloody well don’t want to know,” said Reggie. “If you must, forward the matter to the police in the area. Send them the letters, send them your theories if you wish, and then let the matter drop.”

Reggie found himself pacing angrily toward the window. He stopped and looked back.

Nigel was pretending to contemplate the stains on his desk blotter.

“I want your word on it,” said Reggie, “that you will let the matter drop.”

“I will,” said Nigel, without looking up.

Reggie turned toward the door, then stopped. He spoke too harshly with his brother, Laura had said. He took a long moment unfolding and straightening his overcoat.

“Nigel,” he said, “do you remember how you broke your leg?”

“Yes,” said Nigel. “You knocked me over in a rugby scrum.”

“Not that time,” said Reggie. “Earlier. When you were five. You’d been watching an American serial of Superman. Too many times. You got Mum’s red tablecloth, tucked it into the back of your collar, climbed onto the roof, and tried to fly. Do you remember?”

“Vaguely.”

“Bad idea, roof jumping,” said Reggie. “Squash on Tuesday?”

“I expect so,” said Nigel. And then, after a short pause: “I’ll just tidy things up here a bit.”

Reggie nodded and exited Nigel’s office.

He walked back through the rows of cubicles to the lift. As he pressed the button for the ground floor, he heard someone call out.

He was sorry to see Robert Ocher hurrying up from a side aisle.

Ocher was senior clerk. He was an irritating man but skilled at negotiating Reggie’s fees—and that was a powerfully redeeming quality.

“Busy office tonight,” remarked Reggie as Ocher joined him to wait for the lift. “Working late, are we, Mr. Ocher?”

“No, no. I mean, no more than usual, just trying to get a jump on things, you know. I take it you only popped in to see your brother?” said Ocher, fidgety in his typical way. “I trust everything is going well, since they let him out of—” Ocher stopped; he knew he’d made an error.

“It was hardly Broadmoor, Mr. Ocher. My brother’s hospitalization was completely voluntary.”

“Yes, of course. I only meant that—”

“I know what you meant,” said Reggie.

The lift arrived, and they both stepped in.

“When I said my brother would be helping out with administrative tasks,” said Reggie, “I didn’t intend that he would be answering letters addressed to Sherlock Holmes.”

Ocher gave Reggie a surprised look. “I assumed that you knew. I mean, the lease itself says—”

“Yes,” said Reggie. “I know. I’m surprised at the number of them.”

“Oh, well, there has never been a shortage of crackpots in the world,” said Ocher. “Meaning the letter writers, of course, not your brother.” He forced a little laugh. “When Parsons was here, he easily dispatched the letters in a few moments each day and kept things in quite good order. They piled up a bit with him gone, and I did speak to your brother about that earlier—but of course it’s all quite manageable. I instructed your brother to send just the form reply, leaving ample time for more essential tasks. I trust that is satisfactory?”

“Yes,” said Reggie. “Temporarily.”

“Oh, of course,” said Ocher. “I realize that. Assuming the disciplinary tribunal finds no misconduct regarding that thing in Kent—”

Reggie gave Ocher an irritated look, and Ocher made a quick adjustment.

“Not that anyone could blame your brother, of course.”

“You say that as though someone has.”

“No, of course not,” said Ocher, backpedaling as quickly as he could. “One cannot be faulted for doing one’s job too well.”

“Exactly,” said Reggie. “Nigel will be reinstated. In the meantime, I’ll want you to find someone else to handle those bloody letters.”

The lift had reached the ground floor, and the doors opened.

“Of course,” said Ocher

“Thank you,” said Reggie. He stepped quickly out into the lobby, and Ocher, wisely, stayed in and allowed the doors to close.

Chapter 2

Reggie was annoyed as he got in the Jag. He was annoyed over Nigel’s interruption of the evening with Laura, annoyed that Nigel was treating a letter written to Sherlock Holmes more seriously than his own career, and annoyed, generally, over Nigel being Nigel.

But as he drove out onto Baker Street, Reggie realized what annoyed him most was hearing anyone else blame Nigel for what had happened in Kent. It was bad enough that his brother blamed himself.

Reggie reminded himself that he couldn’t suss out all his brother’s issues in one night. There was just no use dwelling on it.

And he had other concerns.

He drove to Chelsea, parked, and got to Laura’s doorstep. It had been only an hour or two; she might still be awake.

She was. She came to the door quickly, and Reggie saw that she had not changed out of her evening dress; if anything, she was more radiant than when they had parted earlier.

“I’m glad you stayed up,” said Reggie. “How did you know I’d return so soon?”

“I… didn’t.” She bit her upper lip, said, “Come have some brandy, then,” and moved quickly off toward the drawing room.

“What did Nigel want?” she asked as she handed Reggie his glass.

Reggie thought about that for a moment. “A distraction,” he said.

Laura was for some reason still standing; Reggie crossed in front of the fireplace and sat in his usual position on the sofa.

“What sort of distraction?”

“A distraction from the prospect of resuming his legal career, I think. His final hearing before the disciplinary tribunal is pending, and I’ve no doubt he’ll be reinstated.”

“I meant, how did he want to be distracted? Just go down to the Cork and Thistle and get pissed?”

“Nothing so rational,” said Reggie. He told Laura about the letters from Los Angeles and Nigel’s insistence that the woman there was in trouble.

“Is she pretty? This letter writer from Los Angeles?”

“I don’t know. I don’t think Nigel would know either, he hasn’t seen her.”

“Oh. Well, if it’s not about that, then perhaps it’s the Walter Mitty effect.”

“Which is?”

“A study at Harvard or somewhere in America. They surveyed people in different occupations about their work, and then they asked about their daydreams. The more mundane the occupation, and the lower the person’s self-esteem, the more dramatic and heroic and outlandish the daydream. I mean, after discounting all your basic sex fantasies, of course. They called it the Walter Mitty effect.”

“So you’re saying Nigel has low self-esteem,” said Reggie.

“Not necessarily. It’s just an alternative, given that you’ve discounted the possibility that she’s pretty.”

“A week or so back,” said Reggie, “I had a conversation with Nigel that seemed, well… oddly phrased.”

“Odd in what way?”

“He said, ‘You have given Ms. Brinks a raise, I perceive.’ And then he took pains to explain that by observing what she was wearing, and some change in her complexion, and an automobile repair receipt on her desk, he was able to deduce that I had very recently given Ms. Brinks a raise.”

“And had you?”

“No, as a matter of fact. But that’s not the issue. The issue—”

“You should, you know. Give her a raise.”

“Nigel said so as well. But—”

“Ahh,” said Laura. “Then I think your oddly phrased conversation was simply Nigel being too clever in making a point. But if you’re interested, I think I can explain the change in Ms. Brinks. I think she’s having an affair. I’m sure I saw her and some tall man in a baseball cap tucked away in the deepest, darkest corner of Mancini’s last week.”

“Really? I didn’t think she was the type.”

Laura laughed. “You mean you didn’t think she was the age, Reggie. But it just doesn’t cap out that early. Only men are under thirty forever, and only in their own minds.”

Reggie wasn’t sure what that last remark meant. He decided not to ask.

“If Nigel is finding his current job mundane,” he said instead, “and he bloody well should—all he has to do about it is take his legal career back.”

“Oh yes. No such thing as a mundane lawyer.”

Reggie let that go. “He doesn’t have to spend his days filing things. He can get his solicitor’s license back immediately if he doesn’t botch it up.”

“That would be nice. Then he can boss your Mr. Ocher instead of the other way around.”

“What do you mean?”

“I mean I hear him sometimes in Nigel’s office, while I wait for you to finish with a client. He treats Nigel like a subordinate. I think the man has some sort of misplaced power complex.”

“Most chambers clerks do; it’s in the job description.”

“Someone should revise it for him. Nigel is worth ten Ochers. Working with that man would screw up anyone’s self-esteem, unless you were allowed to kick him in the backside every now and then. Say, hourly.”

“I agree. But I gave Nigel the most responsible position he was willing to accept. And if he chafes under the direction of the Ochers of the world, all he has to do is stand up and take his career back. It’s not as though he hasn’t got the mental faculties to— Aren’t you going to sit down?”

She hesitated. “I didn’t expect you back this evening,” she said. She looked at her watch as she said it.

“You could look out for him a bit, you know,” she continued, reinforcing Reggie’s recurring suspicion that before his mother died, Laura must have rung her up and requested a list of the things she could say to get under his skin. “Your brother is not like you. Things don’t always come easily for him.”

“Do you think everything has always come easily for me?”

“I don’t know. Has there ever been anything you truly wanted, Reggie, which you could not attain?”

Reggie was sure there was, but before he could think of it, they heard the front door chimes. Laura did not seem at all surprised, and she went to answer it.

She returned with a guest. Reggie recognized Lord Buxton even before Laura introduced him—tall, bulky, arrogant—his photo had been appearing regularly of late in the Times. Always in connection with the takeover of one unfortunate media corporation or another. A company could not be a small fish in Buxton’s pond for long.

Now Laura got a brandy for Buxton. At the last instant she freshened Reggie’s as well, but it seemed almost an afterthought.

There was an awkward pause. Laura said something about the weather; Reggie and Buxton both stood with their brandies and murmured something in general agreement with her.

Then Reggie mentioned Buxton’s recent American acquisitions, which included a theater in New York and a production company in Los Angeles, and Buxton thanked him for the remark, though Reggie had not intended it to be congratulatory.

Buxton’s first production in America would be The Taming of the Shrew.

“Laura has the fire for Kate,” said Buxton, “and I intend to contemporize it. Might start right in on the motion picture version, too. Add car chases, perhaps have Kate burn down Petruchio’s house. It’s for an American audience, you see. American audiences are different from you and me.”

“Yes,” Reggie said, “they have more money—”

“Laura, I do like his business sense.”

Reggie didn’t much like the manner in which Buxton addressed her or the suggestion that Buxton would know anything of her fire. “And less taste,” he added, whereupon Laura cleared her throat. Buxton gave her a knowing look and laughed from his belly. Laura seemed to be looking at something on the floor.

She was standing now by the mantel on one side of the hearth and Reggie on the other, and Buxton crossed between them and set his glass on the mantel next to hers.

“Well, I must be off,” Buxton said. And then, to Laura, “Can I drop you anywhere on the way?”

She’s standing in her own home, thought Reggie. Where in bloody hell do you think you would get to drop her?

“Thank you, no,” said Laura. She picked up her own glass and smiled. “Good night, Robert.”

“I’ll see you in New York, then,” Buxton said as he picked up his coat. “Let me know if you have difficulty arranging a room—or anything.”

“Good night,” she said again in her firm voice. He paused for a moment, as if expecting something more; then he nodded quickly and slightly in Reggie’s direction and exited.

Laura immediately gathered up the two empty glasses and rushed by Reggie without a glance or a word. He pursued her into the kitchen.

“I’m going.” She whirled to face Reggie, the greens in her dress shimmering like a tropical leaf in the rain. “It is an excellent role, and I’ve already accepted.”

“Going to America to do Shakespeare somehow strikes me as casting pearls—”

“That is precisely why they need to see it done right,” she said sharply.

Then she seemed to reconsider, and she stepped in closer to Reggie. “Or better, anyway,” she said. “It’s only for a short time, after all. And there could be a film role in it.”

“You can’t go to New York,” he said. “It’s a slime pit. They plunk each other like grouse on the motorways.”

She pulled back. “That’s Los Angeles. And I’ve been to football at Manchester. A few rowdy Yanks won’t scare me.”

Reggie was silent. Then, “I’ve never taken you to a Manchester match.”

“There are places you have not taken me, Reggie,” she said, “where I have nevertheless been.”

Laura crossed to the front door now, and Reggie had no choice but to follow.

“When do you leave?”

“Monday. I’m afraid I’ll be mostly packing until then. And getting ready to ‘contemporize’ Shakespeare.”

“When is your flight? I may be able to drive you,” he said, immediately wishing he’d phrased it in a more committal way.

“One-ish, but you don’t have to do that.”

“It’s no trouble.”

“Thank you, Reggie,” she said quite firmly. “But good night.”

She shut the door, and Reggie found himself standing alone, outside, on the chilly step.

And as he drove back to Butler’s Wharf, an image came to mind, pretty much unbidden, of himself, alone in his flat for the next half century, playing snooker in the billiards room with no one, putting a clever spin on the cue ball so that Reggie could not get a shot on the seven. Hair going thin and gray. Stubble on the chin. Stale cigar smoke and the odor of old clothes everywhere.

Had he already waited too long?

A prickly sensation on the back of his neck told him he might have made a mistake. It was a sensation he did not experience often, and he did not like it.

He slept only fitfully that night, and his usual four-mile run along the Thames the next morning did not make the sensation go away.

So he did the run again on Sunday, and by the end of it he had his plan.

He would be careful not to ring her. In these things, as in all things, there was strategy to be considered. It was important not to seem too desperate.

Anyway, she would be packing, and it wouldn’t do to get stuck having to explain himself over the phone.

Better to catch her at the airport tomorrow.

It would be a surprise.

All the ambivalence she had shown of late would vanish; she would call off the trip, and then she would ring Buxton—no, too personal, she would fax him—and Buxton would have to find someone else for his damn play—and for whatever other purposes the pretentious bastard had in mind.

Reggie still had Nigel’s hearing to attend, but it should be a quick formality. He would be out by half-past nine and easily make Heathrow before Laura.

The next day, Reggie drove to the City in plenty of time. He parked in a space reserved for him at Lincoln’s Inn by a young female barrister who had once been his pupil—and something more. As he did so, it occurred to him that he would have to arrange for a new spot. He had not seen the young woman since meeting Laura. And he knew he would not see her again—given what he was going to say to Laura that morning—except in court.

Reggie walked to the Law Society building and went inside to the tribunal’s meeting room. The Society had recently remodeled its digs, and the room smelled distinctly of thick, new forest green carpeting.

Nigel had not yet arrived, but that was not cause for concern. Nigel was usually prompt, but never early.

Reggie took his seat, down left, facing the tribunal that would decide whether Nigel kept his solicitor’s license.

The three members of the tribunal were seated behind a new speaker’s dais, and not in the traditional deep burgundy leather, but in new, ergonomically sophisticated, plush velvet chairs with adjustable armrests that to all appearances were designed to collapse under the least bit of pressure.

On the right was Samuelson. Reggie had handled briefs for him in the past. This would be an advantage. Samuelson would want Reggie’s services again in the future.

On the left was Woolrich, the oldest of the three, who looked ready to nod off. Reggie guessed he would follow the path of least resistance, whatever direction it took.

The two tribunal members on either side seemed to be having some difficulty with the movable armrests. In the center was Breckenridge, who had apparently given up trying to adjust his chair—the height of which made him appear at least a head shorter than the other two—and he sat, with a look of some annoyance, staring at the new built-in dais microphone in front of him.

Breckenridge was the main challenge. Early in Reggie’s career, Breckenridge had shopped a brief at the chambers where Reggie was a junior; the clerk had tried to pass the brief to Reggie, but Breckenridge insisted on someone with more experience. By chance, Reggie was later retained by the opposing party in the same matter—and things worked out badly for Breckenridge

It was two minutes till, and there was still no sign of Nigel.

Now it was time to worry.

Reggie got out his mobile phone and rang Nigel’s home number. No answer.

He tried the office number. No answer there, either. But finally the call switched over to the secretary’s line, and Ms. Brinks picked up.

“I’m at the hearing,” said Reggie. “But Nigel isn’t. Have you seen him?”

“No,” said Ms. Brinks. “His office is still dark.”

“Ring his flat. Call me the moment you locate him.”

“I will,” said Ms. Brinks.

“We’ll proceed, Mr. Heath, if it’s not too great an inconvenience for you,” said Breckenridge.

“Certainly,” said Reggie, closing his phone.

“I suppose you find it necessary to carry as much of the office business as possible with you, now that your chambers are no longer in the City proper?” said Breckenridge, sounding more smug now than annoyed.

“Not typically,” said Reggie, standing to address the panel. “May I take this opportunity to congratulate you on the remodeling? It’s all really quite… remarkable.”

“Congratulations noted,” said Breckenridge. “Can we get on with it?”

“If I might briefly recount the facts for the tribunal?”

“If you feel you must.”

“I do so feel,” said Reggie. He cleared his throat and began, fully aware that there are occasions to be concise and to the point, and there are occasions for oratory, and with Nigel still running late, this was the latter.

“A Mr. Throckmorton,” Reggie began, “a carpenter by trade, was hired by the Corning family to replace rotted wood in the back wall of the pantry. The pantry was adjacent to the kitchen, and on a table in the kitchen, Mrs. Corning had placed a frozen chicken to thaw. The plastic tray on which she so carefully placed the chicken was cracked, and as the bird thawed, it leaked, all the way down to the linoleum floor.

“Very shortly thereafter, the workman—our Mr. Throckmorton—entered the kitchen, slipped on the watery-chickeny fluid, and fell on his backside. All of which was, of course, inevitable.”

“Wait a moment, Mr. Heath.”

“Yes?”

“Inevitable?”

“Yes.”

“Why so?”

“Members of the tribunal, you and I and all in this room know, in our hearts, that fate and chance were forever altered when the first tort law was created, such that the slightest opportunity for creating an injury will always give rise to one, if there is a lawyer available.”

Breckenridge rubbed his forehead. “Please continue, Mr. Heath,” he said, “but without speculation as to what this panel knows in its heart. Or hearts. Or its collective heart.”

“Of course,” said Reggie, and he continued.

“The only question was the extent of damages. And so Nigel called witnesses who testified that Mr. Throckmorton had debilitating pain and paralysis caused by this fall; and the Cornings’ lawyer called witnesses who said there was nothing of the kind, and in my humble opinion it was, at this point, a dead heat. What tipped the scales was Nigel’s summation. Nigel believed his client, and the jury believed in Nigel—and so it came back for the full amount.”

“But what does this have to do with what your brother—”

“I’m almost there.”

“Get on with it, then.”

“Rightly proud of this success and flush with his first commission, and happy in the knowledge that the law, God’s justice, and the solicitor’s pocketbook were all perfectly in sync, Nigel booked a weekend for himself at the most expensive golf resort in Scotland. I forget the name of it, I’m sure some of you know it.

“It was June, and the weather was brilliant. And Nigel was playing so well that he had caught up with the party ahead of him.

“He stopped at a polite distance and watched as the duffer ahead of him took a perfect stance over the ball, swung the driver easily back, and with a fully extended and explosive swing, sent a high arching shot a good hundred and eighty yards onto the fairway.

“And then the man turned, and Nigel saw that this man with the excellent drive was his very own paralyzed client—Mr. Throckmorton.

“Nigel immediately returned to London and told the ethics board what had transpired.”

“We know this, Mr. Heath,” said Breckenridge. “And you will recall that the inquiry found no proof of bad faith on the part of the plaintiff and that therefore there was nothing to be done. The law is not perfect, especially on questions of evidence, and these things do happen. In fact, all that was necessary at that point was for your brother to let it go. But he did not. Unannounced, and with no apparent business necessity, he approached the daughter of defendant Corning at university.”

“There was no other way to go about it,” responded Reggie. “Nigel wanted to put things right. But Mr. Corning was in hospital, having suffered a heart attack shortly after the judgment, and Mrs. Corning threw a plate of tomatoes and bangers at Nigel when he tried at their home.”

“Mr. Heath, your brother intruded into the daughter’s single-gender residence hall after the curfew hour,” said Breckenridge.

“The hours were not clearly posted. And it was the young Corning woman, not Nigel, who was in the corridor wearing nothing but skimpy knickers.”

The tribunal members exchanged glances.

“Be fair,” said Reggie. “They should ring a bell or something before they do that, shouldn’t they?”

“Can be very embarrassing,” Woolrich mumbled, waking up a bit. “Had that same experience myself.”

Samuelson nodded. “Fair warning would be the decent thing.”

“Exactly. And those extraordinary circumstances caused the daughter to misconstrue Nigel’s intent. He was merely trying to return his fee,” said Reggie. “He felt it was his obligation to do so.”

“Was it his obligation to have his hand in his pants?” asked Breckenridge.

“He was just getting the bloody check out of his pocket,” said Reggie. “Everyone at the scene acknowledged that to be so when things calmed down, including the young woman herself, the residence hall guard who came running when she screamed, and all the other young women who came pouring out into the corridor. Nigel had it—the check—right there in his hand.”

The tribunal members huddled together for a brief moment.

“Are we to accept, then,” said Breckenridge, “that all this fuss was because your brother felt the outcome of the case was unjust to the opposing litigant?”

“Spot on, sir. I could not phrase it better myself, though I tried mightily.”

“If so, it’s not a characteristic that seems to run in the family, Mr. Heath. I’ve not heard of you having such compunctions.”

“No argument there. You can see what good such concerns have done Nigel.”

“If your brother takes one approach to the law,” Breckenridge said in a sly voice, “and you take the opposite, doesn’t it stand to reason that one of you is pursuing the wrong profession?”

“Not at all,” said Reggie. “We average out. And in law, as in life, balance is everything.”

“Very well,” said Breckenridge. “You’ve had your say, and we would like very much to dispose of the matter. But we must hear from Nigel Heath himself. It is now a quarter after the hour. Where is he?”

“One moment, if I may,” said Reggie. He took out his phone and rang Ms. Brinks again.

She told him that Nigel still had not shown and that there was no answer at his flat.

Reggie didn’t take her word for it. He called Nigel’s flat himself.

Still no answer.

Reggie put away the phone and addressed the tribunal.

“It is impossible for my brother to appear this morning. He begs your indulgence and conveys his deepest apologies and regrets.”

“Perhaps you will now tell us the reason for his absence?”

“Intestinal flu.”

Everyone paused. Breckenridge drilled in.

“Is your brother in hospital?”

“Ahh… no.”

“Then you’re saying he avoided a hearing that can determine his future licensing merely because he has a temporary and non-life-threatening illness?”

“Because at this moment he is completely incapable of controlling bodily fluids from either of the most likely sources,” said Reggie, leaning back very slightly, enough so that he could casually caress, in full view of the tribunal, the plush and expensive green velvet of one of the newly upholstered chairs.

Breckenridge cleared his throat and shifted uncomfortably. Mr. Samuelson looked at Reggie, recognized the opportunity, and motioned for a huddle with the other two members. For a moment all three heads bowed and leaned in together, revealing one honestly balding spot, one bad comb-over of white hair over quite pink skin, and one insecurely seated toupee.

Then all three looked up, the two on either side sat back in their chairs— one of them voluntarily— and Mr. Breckenridge spoke.

“Very well, then. We will reconvene in three days. If your brother wishes to have his reinstatement considered, the courtesy to notify us would be advisable. Am I making this clear?”

“Crystal, as always.”

“Then we’re adjourned.”

Under the circumstances, postponement was as clear a win as Reggie could expect. He exited the hearing chambers satisfied with the outcome for the moment—but annoyed with Nigel.

The hearing had taken longer than he’d intended, and it was almost ten when he reached the street outside the Law Society building.

The parade of black suits moving up Chancery Lane from the Strand—the male barristers in wigs and dark suits and the occasional chalk stripe, the women in black skirts, with long braided hair under their white wigs—had reached its morning peak.

Reggie stepped back into the shelter of the entryway to ring Laura and was relieved to find her still at home.

“I can’t talk long,” she said. “I’m not nearly packed.”

“Has Nigel rung you?”

“That would have been nice,” said Laura, “but no. Why? You sound… perturbed.”

“The final disposition of his review before the disciplinary tribunal was this morning,” said Reggie, “and he’s nowhere to be found.”

“Well, that’s odd.”

“The hearing’s chaired by Breckenridge,” he added, “and Breckenridge has a memory as long as his nose. If Nigel doesn’t respond soon, Breckenridge will take it as a snub, and he doesn’t take snubs lightly.”

“You must find Nigel and tell him.”

“I don’t know that it will do any good. He’s a grown man; if he wants to toss his career away, I don’t know that I can stop him.”

There was a long pause at the other end of the line, which Reggie interpreted as Laura waiting for him to say something more sensible. When he failed to do so, she spoke again.

“Well, you are his only brother,” said Laura, “so I’m sure you know best.”

Reggie surrendered. “I’ll check his office personally,” he said. “When he wants to convey something without having to hear my response, he’ll sometimes leave a note.” Now he paused.

“Was there something else?” said Laura.

“I would like to see you before you leave.”

“That’s sweet,” Laura said brightly. “But you need to find Nigel, and I can’t miss my flight.”

“Stop at chambers on your way. We’ll get a bite, and you’ll still make your plane.”

There was a pause, then Laura said, “Fair enough. You know how I hate airline food.”

Reggie arrived at Baker Street at midmorning. Clerical workers from the mortgage company that shared the building were still arriving at work, walking through the glass entrance and past the broad marble columns, carrying white paper sacks that smelled of cappuccinos and croissants.

Reggie was already annoyed at Nigel; and hunger, as Laura would have reminded him, made him more so. He tried to keep that bit of self-knowledge in mind as he got out of the lift and headed toward Nigel’s office.

He was halfway there when a commotion became apparent. A cluster of office workers from Dorset National had come upstairs to take a look at something, and Reggie soon realized that the object of their attention had to be in Nigel’s office.

As Reggie approached, the group stopped trying to peer in past the closed blinds and dispersed.

Reggie tried the door. Locked.

He looked in through the corner edge of the window, as the crowd of gossips had been trying to do moments before.

Now he could see why they had gathered.

Only a portion of the room was visible from this angle, and even that was illuminated only by the residual corridor light around the edge of the blinds—but it was enough.

Reggie saw that the drawers on the tall file cabinet had been yanked with such force that they lay open on bent hinges. And all the books on the shelf had been swept off onto the floor. Papers were scattered everywhere.

Nigel had gone off again.

His favorite print of the American West dangled from its wall frame like a flag at half-mast—damage that Nigel in his right mind would never have done. And just barely visible in the dark corner above the top edge of the file cabinet was an empty shelf where Nigel’s prized Remington bronze had been on display.

“Odd, isn’t it, Mr. Heath? I didn’t know quite what to make of it.”

Reggie turned with a start. He hadn’t seen Ms. Brinks come up next to him.

“Don’t let anyone near,” he said to her.

Reggie took a key from her, opened the door, stepped inside alone, and shut it quickly behind him.

He stood just inside the doorway and looked left to right to take it all in. Everything was chaos—folders, forms, and legal papers of all sorts tossed about; all the books dumped to the floor, spines broken and flattened. Everything that could be had been torn, gutted, dumped, or bent.

Everything but Nigel’s hearing notice from the Law Society—that document was folded over and taped securely to the near corner of Nigel’s desk, with Reggie’s name written on the back of it in blue felt pen.

Reggie detached the document and unfolded it.

There was a short note written on the inside. It was unquestionably in Nigel’s hand, and it said this:

Can’t make hearing. Sorry. Just let it go.

N

As he read this, Reggie heard the door latch turning behind him.

“I said no one,” he called out.

The door opened anyway. It was Laura.

“You shouldn’t invite me to brunch and then tell me to sod off,” she said. She stepped inside. “Do you know you have people gathered about as if— Oh my.”

“I pushed him too far, didn’t I,” said Reggie.

“What do you mean?” she said.

He handed her the note Nigel had written. “You said it yourself—he only got out a month ago. I leaned on him just a bit—and now this. It’s just the same as last time. He’s trashed his office, and by now I’ll bet he’s checked himself into the asylum again.”

“Recuperation center,” said Laura, reading the note.

“Whatever.”

She gave the note back to Reggie. “Well,” she said, “if he doesn’t want to be a lawyer, I guess you can’t make him be.”

“Agreed.”

“But I think you’re wrong about what’s happened here. I think it’s a burglary.”

“What is there to burgle?”

“I don’t know, but—” Laura stopped suddenly. Her nose wrinkled.

“What?” said Reggie.

“That smell,” she said.

She walked toward the other side of the desk, the side that had not been visible through the window.

She stood near the shelf where the Remington bronze should have been. Then she looked downward, behind the desk.

She gasped and put her hand to her mouth.

Reggie crossed to the other end of the desk, following Laura’s stare. Then he froze.

On the floor behind the desk was the bronze of American Indians hunting buffalo—a replica, but even so not inexpensive by Nigel’s standards—and something that would never be found on the floor of his office. But that was merely odd.

What stopped Reggie and Laura in their tracks was what lay next to the bronze and the damp, thick scent that accompanied it.

It was Ocher. Or at least had been. He was lying silent and still on the floor, and with pupils fixed as stone.

The bronze Remington sculpture was coated on one long side and a corner with something dark, reddish, and crusted around the edges.

“It is…it is Ocher, isn’t it?” said Laura.

“Yes. You aren’t going to faint, are you?”

“Why on earth should I faint?”

“You’re rather leaning against the file cabinet. I thought perhaps it was for steadying.”

“I’m trying to look casual. For your secretary’s benefit. I’m afraid she’ll hurt her nose, mushing it up against the window like she is, and— Oh, too late, here she comes.”

Ms. Brinks was in the doorway. Before Reggie could stop her, she stepped up to the desk and tried to lean over to see what Reggie and Laura were looking at.

“Oh!” said Ms. Brinks. “Oh my.” She jerked backward at first, then just stared. “Is he…”

“Yes,” said Reggie. “Please go out and ring the police, will you? And make sure no one else comes in here.”

Ms. Brinks exited, and Laura knelt along with Reggie over the body.

“Should we try… I mean… that resuscitation thing?”

“I’m afraid that ship has sailed,” said Reggie.

“You’re not saying that simply because you never liked him, are you? I mean, I can do it if you don’t want to. Although I think I heard him say once that he eats kippers for breakfast.”

“He has no breath and no pulse, his pupils are completely fixed, and his skin is like a Yorkshire pudding that’s been in the fridge. Whatever good points he once had, they’re all completely gone, along with his more predominant qualities.”

Laura leaned in for a closer look. “Yes, I see now. You’re quite right. Oh, do you suppose this is—”

“Don’t—” began Reggie as she reached for the bronze, but it was too late.

“I’m only touching the edges,” she said, holding the bronze quite gingerly in three slender fingers. She turned it base upward. One of the sharp corners at the heavy bottom edge was thick with recently congealed blood.

“Rather nasty,” said Laura.

“Yes,” said Reggie. “But let’s leave it as we found it, shall we?”

“Of course,” said Laura.

She put the object back on the floor where she had found it. She regarded it for a moment, then said, “No, I think it was more like this.”

She adjusted it ever so slightly, then she stood and looked from Ocher’s body to the mantel where the sculpture had been displayed.

“You don’t suppose it could have simply—fallen on him, do you?” she asked.

“Not with that much force,” said Reggie.

Laura considered that. “I suppose then suicide is out of the question as well,” she said without much enthusiasm. Then, for a short moment, neither of them said anything.

“Well,” ventured Laura, “this might have been a burglar, and Ocher catching him.”

“Yes.”

“But if it was not a burglary, then the next likely scenario would be… well, Ocher is—was—a very unlikable man, any number of people might have wanted to bash him with something sharp and heavy.”

“In Nigel’s office.”

“You’d bash him where you find him, I would think,” said Laura.

“Well, you’re right about the unlikable part. But the geography is unfortunate.”

She gave that due consideration, then said, “Nigel could not have done it.”

“Of course not,” said Reggie.

“He would never abuse his Remington that way.”

“You’re right,” said Reggie, “but I hope he’s got a better alibi than that.”

“What’s making that annoying hum?” said Laura.

Reggie listened. He knew the sound, but he was so accustomed to hearing it in Nigel’s office that he hadn’t noticed.

It was Nigel’s computer. Reggie had assumed it was off, but he looked now and saw that, yes, the computer was still on. Only the monitor had been turned off.

Reggie pushed the monitor’s button, and it began to flicker. Then the display came up, and right in the center was the text of an opened message. It was from Transcontinental Airlines. It read:

Thank you for confirming your reservation on:

Flight 2364 to Los Angeles

Departing at: 8:45 A.M.

Do you wish to perform another transaction?

Yes/No

“Bloody hell,” said Reggie.

“Why on earth Los Angeles?” said Laura.

“The bloody letter,” said Reggie. “He’s gone to Los Angeles over the bloody letter to Sherlock Holmes.”

Laura pondered that for a moment, then said, “And do we think that was before… Ocher was killed? Or after?”

Reggie looked at Laura, and they both grasped the implications of what she was asking.

“Of course it had to be before,” she said quickly.

“Yes, it must have been,” said Reggie. “Ocher heard something after Nigel was gone. He came in, around the desk, and then someone concealed here, behind the file cabinet, struck him with the first object at hand.”

“Yes,” said Laura. “Because otherwise, if Ocher were here first, and Nigel came in after, that would mean it was Nigel who—”

She didn’t try to finish that sentence, and now there was a knock at the door.

Ms. Brinks stuck her head in. “The police are here,” she said.

Reggie nodded to Laura in the direction of the corridor where the police were approaching.

“I’ll just say hello to them,” she volunteered, and stepped out of the office, closing the door and taking Ms. Brinks with her.

Reggie knew he would be alone in the office only for a moment.

Nigel had gone to Los Angeles—but where?

Reggie turned to Nigel’s filing cabinet. It had been gutted, all its hanging folders yanked out and their contents dumped on the floor.

He began to look about for the envelope in which Nigel had been keeping the letters. He didn’t see it.

And then he did.

It was under Ocher. Under Ocher’s left forearm, to be exact, as if for some reason he had been clutching it when struck.

That was disturbing.

Reggie reached down and tugged on the envelope—gently at first and then with a bit more force—to pull it out from under Ocher, just enough to look inside.

It was empty. The enclosures it had contained—which Reggie had refused to look at the other night—and the letters, including the letter writer’s name and return address, which was almost certainly Nigel’s destination—were gone.

Reggie could hear Laura trying to chat up the police outside in the corridor, but it apparently wasn’t slowing them much; they were right outside the office now.

There was no time for anything more. Reggie gave the computer’s plug at the wall outlet a quick nudge with his foot. The monitor’s display crashed out in a hazy blitz of blue and black, and Reggie managed to step away and into the doorway just as the two officers—one of them a woman, which perhaps explained why Laura had not been able to delay them longer—pushed open the door.

“Thank you for coming so quickly. I assume you have an inspector on the way?” Reggie said to the male sergeant.

“Detective Inspector Wembley will be here, sir.”

“You didn’t touch anything?” said the female officer, crossing around behind the desk to view the body.

“Just as we found it,” said Reggie.

“I picked that thing up for just a bit, though,” Laura said innocently, pointing at the statue.

“Inspector Wembley won’t like that,” the male officer said in an annoyed tone directed at Reggie rather than Laura. “Not quite untouched, then, is it?”

“Reggie didn’t say it was untouched,” offered Laura. “He only said it is as we found it, and it is—I put it back quite exactly. Although I admit you do have to watch Reggie and his words; he’s a QC, of course, and likes to prove it more often than really necessary.”

“Yes, we know Mr. Heath is a queen’s counsel,” said the female officer to Laura, rather dryly. “We got that from the nameplate.”

“Did you say Wembley?” Reggie asked the sergeant.

“Yes, sir. Do you know him?”

“We may have met. Ms. Brinks will be available to him here when he arrives. I’ll be in my chambers office, at the opposite corner.”

“Very good.”

Reggie walked with Laura back to his own office and shut the door behind them. They were alone, for the moment.

“You might have left out the dissertation on the sculpture,” he said.

“I was being diverting.”

“You’re always diverting.”

“I mean diversionary. I was creating a diversion,” said Laura. “You couldn’t tell?”

“Diversion from what?”

“From them seeing you were impeding their investigation. The computer was on when I left, and off when I came back. I’m sure you did what was necessary, but I didn’t want them to notice. They might have touched it and found it still warm, you know.”

“You’re being quite tactical, given that we know Nigel didn’t do it.”

“So are you. The police can make mistakes, we both know that, and we’re trying to help them not make one here. But at least I’m not doing anything that could be considered obstructing. You did, and I wish you wouldn’t. It’s difficult enough just trying to protect one of you.”

Reggie sat down. After a moment, he said, “Then you think it’s possible Nigel needs protecting?”

“I didn’t mean it that way.”

Reggie nodded. “It doesn’t help that Wembley is investigating.”

“Why?”

“I destroyed him in a cross a few years back, when I was doing criminal.”

“So you’re worried about a karma thing, or do you think he holds a grudge?”

“Shouldn’t matter, I guess. No doubt he’s forgotten all about it.”

There was a short pause. Then Laura said, “You know my plane leaves in little more than an hour.”

“I know,” said Reggie.

“I could hardly leave if I didn’t know Nigel would be all right.”

“I will see to Nigel,” said Reggie. “You must go to New York, exactly as you had planned. If you delay it, Wembley will think you are hanging about out of concern for Nigel, and that will just increase his suspicion.”

“What will you do?”

“I’m going to Los Angeles. Wembley won’t like it, but he’s got nothing with which to stop me at the moment. I think it’s a safe bet that Nigel went there to see the girl. That’s where I’ll start. With luck I’ll find him and figure out what’s going on before Wembley does.”

“Wouldn’t it be better to stay and wait for your brother to contact you?”

“Have you ever known Nigel to ask for help when he should?”

Laura had no answer for that.

“No,” said Reggie, “I haven’t either, and I’ve known him thirty years longer than you. And you know he’s been like that even more so since… well, since you and I…”

“No,” said Laura. “I don’t think I do know that. But I know you think it.”

Laura said that as if there were more to discuss on the issue, but Reggie avoided it. “Point remains,” he said, “what ever Nigel’s dug himself into, he’ll only dig it deeper if I don’t reach him. Wembley will already think he’s found means and opportunity. I won’t be able to stop him from grilling the staff, and if he asks the right questions and gets the wrong answers, he might think he’s found motive as well. As you said, they make mistakes.”

Now Ms. Brinks was at the door.

“Inspector Wembley is here,” she began, but that was as far as she could get.

“I’ll only need a minute, Heath,” said a voice from behind her, and now the door opened fully and the detective stepped in without invitation.

Yes, that was the Wembley, Reggie remembered.

“How are you, Wembley?”

“Better than your clerk,” said Wembley. Then he turned toward Laura. “You’re Laura Rankin, aren’t you?”

“Yes,” said Laura.

“I saw you in Chicago. The play, I mean. It was a bit over the top for my taste, but not you—you were captivating.”

“Thank you,” she said. “It’s always comforting not to be lumped in the over-the-top category.”

“It was you found the body?”

“No,” replied Laura. “Reggie found the—Mr. Ocher. I came in after.”

“Oh.” Wembley nodded.

“He was a horrid little man, you know. Mr. Ocher,” continued Laura.

“Really?” said Wembley.

Reggie knew Laura was being diversionary again, and he tried to give her a cautioning look behind Wembley’s back—but she ignored it.

“He had more annoying little qualities than I can even begin to recount,” she said to Wembley.

“Knew him well, did you?”

“Only from my visits to Reggie’s chambers. I mean the legal chambers, of course. Not Reggie’s other chambers.”

“So you didn’t get on with him, then?”

“Not a bit. I rather despised him, and I’m sure he felt the same about me.”

“Laura—”

“Well, I don’t know that he didn’t.”

“You’ll understand that I have to ask you this,” began Wembley. “Just as a matter of form—”

“Yes?”

“Where were you last night, and early this morning, say, between the hours of—”

“Home in bed,” said Laura. “Rather, alone. No one saw me there at all.”

Wembley had a look on his face that said “More’s the pity.” Reggie decided it was time to interrupt.

“Miss Rankin is due in New York,” he said. “She has rehearsals starting immediately. There’s no need to delay her, is there?”

“Not on my account,” said Wembley. “Professionally speaking. But it’s the City’s loss whenever you are away, Miss Rankin.”

“Thank you again, Inspector Wembley,” said Laura. She kissed Reggie lightly on the cheek and turned toward the door.

“The hotel you’re at?” Wembley said suddenly as she turned the latch.

“Something over Central Park,” she said. “Reggie always knows how to find me if I’m needed.” She stepped out and closed the door behind her.

There was a pause for just a moment after, before Wembley said, “You’ve done well for yourself, Heath.”

He seemed to be looking about at the room as he said it, but it wasn’t clear that the chambers was what he was referring to.

“Sit if you like,” said Reggie.

Wembley declined and then said, “We’ll hear what forensics has to say, of course. One doesn’t want to be hasty—how do the Americans say it, to…”

“Rush to judgment.”

“Yes. But it’s rather hard to see it as accidental.”

“I’m sure you must be right, but it’s not my field. I don’t know much about criminal matters.”

“Quite. I recall how little you knew,” said Wembley. Then, “Did Ocher have conflicts with anyone I should know about?”

“I don’t know much about his personal life.”

“I meant in the workplace.”

“Ocher annoyed pretty much everyone he worked with, none more so than I. He thought it his duty as senior clerk, and quite right about it, too.”

“Hmm.” Wembley, standing in the middle of the room, put his hands in his pockets, hooked by the thumbs, rocked back on his heels slightly, and took a moment to look about at the appointments for Reggie’s chambers.

Then he began again.

“So Mr. Ocher was in your brother’s office when he was killed?”

“I don’t know. That’s where we found his body.”

“Does your brother generally lock his office?”

“I’m not sure.”

“There was no sign of forced entry, you see.”

“I don’t know that Nigel does lock his office, but in any case, Ocher has his own key.”

Wembley nodded slightly. “Anything taken that you know of ? I mean, it does look like a possible burglary, I’ll grant you. But was anything actually taken?”

“I don’t know.”

“Hmm,” Wembley said again. “Quite right. Yes, I expect I’ll need a word with your brother, won’t I? Is he about?”

“I’m afraid not.”

“Expect him soon?”

“I’m afraid he’s… on holiday.”

“That is unfortunate. When did he leave?”

“I think last night,” Reggie lied. “But I don’t know exactly when.”

“Returning?”

“A few days, I expect.”

“Where is he taking this holiday?”

“He didn’t say.”

“Not close, then, you two?”

Reggie shrugged.

“Have him ring me when you hear from him, will you?”

“Certainly,” said Reggie.

“Computer was warm,” said Wembley, turning suddenly. “Know anything about that?”

“No.”

Reggie stood and opened the office door; Wembley exited, and Reggie watched until he had seen him enter the lift, the doors close, and the indicator lights show that the lift was actually on its way down.

Then Reggie went to his own files and opened his list of contacts from the inception of the Dorset House lease. It was a very thorough list, with contacts for people with all sorts of connections with the Dorset National Building Society. Now there was one that he needed.

He found it.

It was an address in Theydon Bois. Out of the city, but not all that far.

Reggie took the back stairs out of the building, looked quickly about for Wembley, and then got in the XJS.

With any luck, he’d get what he needed and still make an evening flight from Heathrow.

Copyright © 2011 by Michael Robertson

Michael Robertson works for a large company with branches in the United States and England. His first novel in this series, The Baker Street Letters, has been optioned by Warner Bros. for television. He lives in San Clemente, California.