Robert Mitchum as Philip Marlowe: An Investigation

By Brian Greene

Raymond Chandler’s novels featuring private investigator Philip Marlowe are perfectly ripe for film adaptation. The evocative atmosphere in those books, along with the memorable characters and suspense-rich plots, makes them ideal for transference to the big screen—particularly via the film noir style. Two of the better movies of that kind were created from Chandler’s stories in the film genre’s golden age: Murder, My Sweet (1944) and The Big Sleep (1946).

But what about the two films that were made in the mid-to-late 1970s that come from the same two novels as the above mentioned? They starred Robert Mitchum, himself a leading figure of vintage film noir, at the latter stage of his acting career. Shout! Factory has just released a new BluRay edition of the two ‘70s movies featuring Mitchum as Marlowe, and this invites a discussion about those two in relation to their predecessors as well as the Chandler novels on which they’re based.

Let’s start with The Big Sleep, although it was the second of the two films in which Mitchum portrayed Marlowe. Most reading this are probably well familiar with the plot of Chandler’s debut novel from 1939, but for the sake of conversation, a quick rundown: Marlowe’s client is a wealthy old man, General Sternwood, who has two wild daughters, both of them young adults. The younger girl is mentally unstable, to boot. Sternwood, a widower who had his two children when in his early 50s, was recently mailed some I.O.U.s signed by Carmen, his second daughter, the debts apparently having been assumed via gambling. The debtor is a book dealer of some kind. The General wants Marlowe to silence the letter sender, who is likely a blackmailer who will keep asking for more Sternwood money if and when the present bills get paid. As Marlowe plunges into his work and gets acquainted with the sordid lives of his customer’s two reckless children, he finds himself enmeshed in a world populated by a smut book peddler, a casino owner who functions like a mob boss, some common grifters, etc. And he learns just how much trouble can be raised by two rich, undisciplined young women who like to live on the edge.

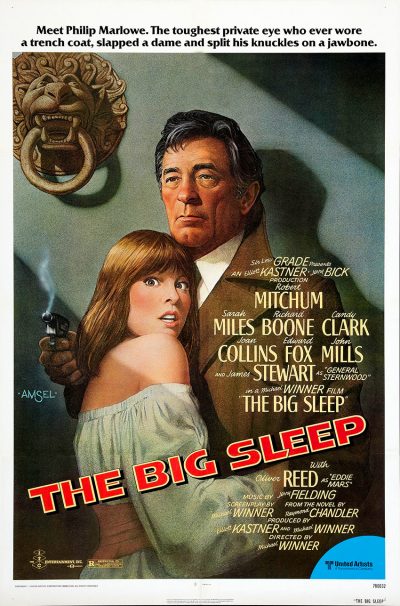

It took some nerve from movie director Michael Winner to do a remake of The Big Sleep in 1978 when he had to know it would inevitably draw comparisons to the revered 1946 version, directed by Howard Hawks and starring Humphrey Bogart as Marlowe and Lauren Bacall as the elder Sternwood daughter. Maybe that’s part of why the English filmmaker set his version in London rather than Chandler’s Los Angeles—as one way of differentiating his film from Hawks’s. Winner brought in some heavy hitting thespians to act alongside Mitchum. Jimmy (billed as James) Stewart portrays General Sternwood, and Oliver Reed, with whom Winner had a long-running cinematic partnership, plays the gambling house master Eddie Mars. Joan Collins, a few years before her celebrity standing was revitalized by way of the TV show Dynasty, had the role of a sexy lady con-artist out to financially exploit the Sternwoods and others with whom they’re involved.

It took some nerve from movie director Michael Winner to do a remake of The Big Sleep in 1978 when he had to know it would inevitably draw comparisons to the revered 1946 version, directed by Howard Hawks and starring Humphrey Bogart as Marlowe and Lauren Bacall as the elder Sternwood daughter. Maybe that’s part of why the English filmmaker set his version in London rather than Chandler’s Los Angeles—as one way of differentiating his film from Hawks’s. Winner brought in some heavy hitting thespians to act alongside Mitchum. Jimmy (billed as James) Stewart portrays General Sternwood, and Oliver Reed, with whom Winner had a long-running cinematic partnership, plays the gambling house master Eddie Mars. Joan Collins, a few years before her celebrity standing was revitalized by way of the TV show Dynasty, had the role of a sexy lady con-artist out to financially exploit the Sternwoods and others with whom they’re involved.

Besides the change of locations, there are other aspects that distinguish the 1978 edition of The Big Sleep from the original movie version of Chandler’s novel. One is that Mitchum as Marlowe uses voiceovers to tell parts of the story. Another is that Winner’s version sometimes has a more explicitly violent, grotesque feel than Hawks’s, befitting of the different eras in which the two films were made, and not surprising since the ’78 version was overseen by the same man who brought us Death Wish (1974). Winner’s film is also sleazier than Hawks’s, again apropos of the late ‘70s. We see one of the naughty books distributed by the man who sent Sternwood the letter about his daughter’s gambling debts, for instance, whereas that kind of thing is muted in the ’46 film. Under Winner’s direction, the younger Sternwood daughter appears in the nude in a few scenes, just as she does in Chandler’s book—not something a mainstream filmmaker was going to try to get away with in 1946. Another difference between the two films is that the homosexual aspects of Chandler’s story are shown more openly via Winner’s direction than they were by Hawks’s. Despite altering the setting and making several characters English rather than American, Winner seemed intent on duplicating some of the fine details from Chandler’s book, down to things like the silver fingernail polish Collins’s character wears—not the kind of thing Hawks fussed over.

The Big Sleep brought in mixed reviews upon its release in 1978. Roger Ebert, for one, didn’t think it compared well to the 1946 version. But the film has some things going for it. Mitchum displays his usual mastery of the big screen and works well as Marlowe, even if he seems like a different kind of guy than the one played by Bogart. And Oliver Reed is perfect as the snake-like Eddie Mars. Taken at face value, it’s a good—even if not great—seedy, late ‘70s crime film with some hall of fame-level actors doing their thing. The biggest problem with the movie is the character of the younger Sternwood girl. Candy Clark plays her in such an exaggerated, forcedly quirky way that she is too ridiculous to be taken seriously. Her character comes close to ruining the movie. And when compared to the Hawks version of the story, the primary shortcoming is that there’s nothing in Winner’s edition to replace the powerful on-screen rapport between Bogie and Bacall, which is so much of what makes Hawks’s version a classic. But if you’d never seen the 1946 movie and took the 1978 one in and judged its quality solely by its own merits, you could say it’s a well-told, edgy ‘70s crime film.

In my opinion, Chandler’s second novel, Farewell, My Lovely (1940), is one of his best—in a two-way tie with The Long Goodbye (1953). The story has so many subplots that briefly summarizing all of them will be a challenge. But here it goes: Marlowe has a chance encounter with a supersized man who has a short fuse, a murderous grip, and a fixated state of mind. This guy, Moose Malloy, has just been sprung from prison after doing an eight-year stretch. He’s looking for the lady who was his sweetheart when he was last on the loose, and he wants Marlowe’s help locating her. Marlowe agrees, however reluctantly, and soon finds himself surrounded by a cast of people who make the characters from The Big Sleep look neighborly and wholesome by comparison. There’s an effeminate playboy who may or may not be part of a jewelry heist gang, a psychic consultant who is definitely involved in sinister deeds, a classic femme fatale, a frowsy widow who likes liquor too much but might not be as out of it as she appears, some crooked cops, and so forth. And everybody seems to have a gun and/or sap on hand in case they need to inflict harm on someone who gets in the way of their dirty doings. There might actually be a few decent people Marlowe encounters along the way. But you have to read the book to find that out.

The 1944 film Murder, My Sweet, based on Farewell, My Lovely and directed by Edward Dmytryk, doesn’t have as large a lasting reputation as the 1946 movie version of The Big Sleep. But it’s as worthy as Hawks’s film adaption of Chandler’s fiction. Dick Powell works well as Marlowe, Mike Mazurki should have gotten a Best Supporting Actor Oscar nomination for his spot-on portrayal of Moose Malloy, and there are dream sequences worthy of Dali. The film took in a slew of Edgar awards in its day.

So, just as with the 1978 The Big Sleep, the ’75 film Farewell, My Lovely, starring Mitchum as Marlowe, was up against it in attempting to equal a previous cinematic version of the tale. The movie, which was directed by Dick Richards, has some flaws, both in and of itself and in relation to Murder, My Sweet. Parts of the film are too stylized to the point of being cliché-addled. Some of the acting performances are wooden. And anyone who’s seen Murder, My Sweet will likely find Jack O’Halloran’s portrayal of Moose Malloy noticeably inferior to Mazurki’s.

But there’s plenty good to say about Farewell, My Lovely, the movie. The best thing about it is Mitchum, who is convincing and enjoyable to watch in playing Marlowe, just as he is in The Big Sleep. Charlotte Rampling is also strong as the femme fatale. The story moves along briskly on the big screen and keeps you interested. And then there’s gravy: like Harry Dean Stanton shining in a smallish role as an ill-tempered cop, and the presence of noir fiction great Jim Thompson as Rampling’s character’s rich but mentally broken elderly husband. Sylvester Stallone fans might enjoy seeing him in an early (tiny) role. Like Murder, My Sweet, this title takes some liberties in deviating from Chandler’s novel while staying mainly true to the crux of the book’s plot. If you can watch this feature without comparing it to Murder, My Sweet too much, and if you can withstand some of the clichés and poor acting, it’s a good mid-‘70s film noir ride.

Take in both of the Mitchum as Marlowe films back to back if you have the time. Then, go back later and watch or re-watch the ‘40s films that pre-dated them. And if you haven’t read the two Chandler novels under discussion, your next homework assignment has just been made.

Comments are closed.

Hi Brian: I enjoyed your review of the Philip Marlow films. I have seen both films and read all the novels. I frankly find Mitchum to be the most believable Marlow of any of the actors to have played the character. Bogart, while a great actor, was a bit underweight to be the Marlow of Chandler’s novels. It is too bad that Mitchum didn’t get to reprise the role in a remake of The Long Good-by. Best regards, Jeff

I have to agree with Jeff. Bogart had too much nervous energy. Mitchum is – tired. Disappointment is stamped on his face.

theodolite