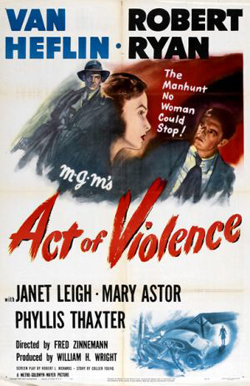

The greatest noir revenge tale is probably Fred Zinnemann’s Act of Violence (1948). One of the underrated masterpieces of the genre, the movie tells two stories: one about a family man named Frank Enley (Van Heflin) and the other about a disturbed ex-serviceman named Joe Parkson (Robert Ryan). Frank’s a happy man, a war hero who has returned from overseas and made the best of the postwar American utopia. He’s got a pretty young wife, a healthy two-year old son, and plenty of friends and money. And then Joe Parkson gets to town.

I don’t want to say too much about the plot, and I certainly don’t want to reveal Joe’s reasons for wanting to kill Frank. Their connection goes back to the war, but uncovering their shared history is pivotal to the enjoyment of the film. Figuring out just how much of the darkness encroaching on this small town ideal is represented by Joe and how much of it is represented by Frank is just one of the film’s great surprises.

Since Lang was a master of mood and action, this film has all the atmosphere and ass-kicking you could want out of a classic film noir. All Bannion wants is to mess up the crooks who killed his wife. The Big Heat, as many people have noted, really set the standard for Dirty Harry and all the righteous renegade cop movies that came after it. For instance, Bannion addresses every criminal in the movie by the pejorative “thief”—as in “You’re outta business, thief.” Listen to how Ford spits out that word and you can hear the embryo of Eastwood’s “Well, do ya, punk?”

Glenn Ford’s everyman face belied an intrinsically introspective quality as an actor, and here he seems to be imploding with rage. Likewise, Grahame is perfect as the floozy girlfriend who realizes too late that her easy life has already come to an end. She spends the last third of the movie with her face half-concealed in bandages, and the scenes where she sets out to get her revenge—armed with a mink coat, a gun, and a boiling pot of coffee—are classic.

This is a terrifying movie, and the years have not diminished its impact. Director J. Lee Thompson is working in the Hitchcockian mode, and while he sometimes presses too hard, overall he achieves impressive results. The last thirty minutes of this movie are as tense as anything the Master of Suspense ever put on film. Thompson is assisted greatly by the excellent cinematography of Sam Leavitt, who paints burning Carolina days and then plunges the night scenes into pervasive blackness. And Thompson’s taut filmmaking is nearly inextricable from Bernard Herrmann’s brilliant score. It’s no coincidence that Martin Scorsese’s otherwise lamentable remake of Cape Fear in 1991 kept Herrmann’s creepy music. It is one of the composer’s great scores, and it only serves to reinforce the Hitchcock comparisons.

At the heart of the film is the performance by Mitchum. Because he was one of noir’s greatest leading men, it is sometimes forgotten that Mitchum was also one of its creepiest villains. The key to his frightening turn as Max Cady is the utter righteous indignation he brings to the role. At the heart of any movie that deals honestly with revenge is exactly this truth: everyone thinks they’re in the right.

Other revenge-based film noirs of note:

- Scarlet Street (1945)—Fritz Lang masterpiece about a lonely painter played by Edward G. Robinson taken for a ride by femme fatale Joan Bennett and her pimp boyfriend Dan Duryea. Contains the most brutal murder scene of the 1940s.

- Cornered (1945)—Dick Powell stars as a concentration camp survivor trying to track down a Nazi who mastermind the massacre that killed his wife. Surprisingly blunt about the horrors of war.

- The Killer Is Loose (1956)—Psycho Wendell Corey hunts the cop (Joseph Cotton) he blames for the death of his wife. Director Budd Boetticher’s only noir. Not to be missed: the bizarre finale with Corey, in drag, stalking the cop’s wife down the street.

- Tension (1950)—Geeky Richard Basehart sets out to kill the guy who stole his wife. And underrated gem with a fantastic performance by sexy Audrey Totter as Basehart’s faithless wife.

Jake Hinkson, The Night Editor

PS: Most of these movies are available on DVD. Act of Violence, for instance, is available as part of the Film Noir Classic Collection #4 (an excellent collection, btw). It comes with some wonderful commentary by Dr. Drew Casper.