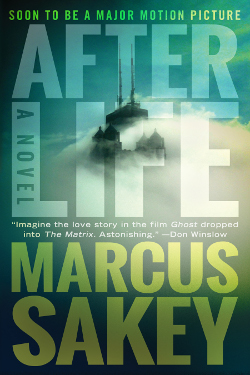

Markus Sakey is a novelist and screenwriter whose books have sold more than a million copies and been translated into dozens of languages. His titles include The Blade Itself, Good People (which was adapted for film and starred James Franco and Kate Hudson), and the Brilliance Trilogy: Brilliance, A Better World, and Written in Fire. Mr. Sakey’s newest, Afterlife (available July 18, 2017), is a standalone thriller that’s already been optioned for film by Imagine Entertainment with the author attached to write the screenplay.

Recently, the Chicago-based author generously made time to answer questions about creative inspiration, the importance of setting, genre classification, and the challenges of turning a full-length novel into a screenplay, among other topics.

What was the initial impetus for writing Afterlife, and why did a standalone appeal to you after concluding the Brilliance Trilogy?

It’s usually hard to pinpoint where ideas come from, but this one I know—it came from a dream. I was in Chicago, a perfectly familiar Chicago except that everyone else was gone. And with that dream certainty, I realized I was dead. Everyone else wasn’t gone; I was.

It was okay. It wasn’t a nightmare. Then, I woke up and saw my wife of 20 years sleeping beside me, and I imagined being in this world but at a 90-degree angle to it. Being near her but unable to speak to her, touch her, or interact in any way.

And it became a nightmare. The kind with enough juice that I knew I had to write it.

As for it being a standalone, that’s always been my preference. The Brilliance Trilogy is the exception for me, and it’s really one story told across three novels. As a writer, I like a beginning, middle, and end, and then I like my imaginary friends to clear out and make room for new ones.

Though the story is “otherworldly,” it has many timely and relevant elements. How did the current world climate inspire your conceptualization, and why is the lens of fiction a powerful one to use in exploring “real life” issues?

I consciously set out to write a myth. The magical thing about myths is that they can be true without being real. That’s a defining characteristic. Consider the Ancient Greeks—do you really think they believed the sun was a god in a gilded chariot who crossed the sky daily? I don’t. I think they knew it wasn’t real. But it had a truth beyond its reality. The mere act of casting a story around it, like a net, puts form to the world. Stories shape the void.

To my mind, there are few better ways to capture the real world than via fiction. Fiction can personify, orient, collate, and organize. It’s a method by which the chaotic world can be put into a sensible structure. It lets us make sense of senseless things and experience lives not our own.

Plus, it’s just the best thing in the world.

What do you see as the role of paradox (love vs. hate, hope vs. despair, etc.) in this story, and how do Will Brody and Claire McCoy’s life experiences allow them to appreciate both sides of such complexities?

I’m not sure this is exactly a paradox, but for me, one of the central elements in the novel is that Brody and Claire will do almost anything to reach one another—and yet, at the same time, they will risk their own happiness to fight for the right thing.

To my mind, there are few better ways to capture the real world than via fiction. Fiction can personify, orient, collate, and organize. It’s a method by which the chaotic world can be put into a sensible structure. It lets us make sense of senseless things and experience lives not our own.

Plus, it’s just the best thing in the world.

They are lovers and monster-hunters. Both parts are fully true, and each influences the other. It was a fun dynamic to write characters who will do anything for a life together while also being willing to throw it all away if that was the cost of beating the bad guy. To write characters for whom the latter was part of what justified the former.

You use a futuristic version of Chicago (where you currently live) as a backdrop. How does setting enhance narrative, and in what ways does knowing the city intimately inform your portrayal?

I like writing about Chicago. It might be because it’s my home, or it might be that it’s my home because there are so many stories about it to like. My previous four books didn’t really fit with a Chicago locale, so it was a pleasure to come home.

Sort of.

Most of the Chicago in my book takes place in what I call the Echo. It’s a sort of dark reflection of the world, one which is correct in every detail except the people. The only people are, well, dead, and yet they find themselves here, cast into a world at once familiar and strange. They are fighting for what remains of their lives, but they are also living after death—forging community, making friends and lovers, wrestling with the existential questions.

Knowing the city gave me a strong foundation to write that. But at the same time, I loved the novelty of writing a mirror of Chicago—as I was writing, everywhere I went, I imagined, “Hey, what would this be like in the Echo?”

The book has been classified as science fiction. In what ways does the idea of genre both help and hinder an author, and how do you personally view this work?

Genre is a tool for organizing bookstores. It tells you which aisles you do or don’t want to go down. That’s it. Seriously, that’s it.

For me, there are two kinds of writing: good and not. All an author can do, our whole job, is bust our butt trying to land in the former. That means planning stories that inspire, rendering characters that people will miss, and polishing every line and every word. That’s my job, and I love it, and I care far more that people enjoy the work than I care what they call it.

Afterlife is being adapted for film, and you are writing the screenplay. What are the greatest differences between novelization and scriptwriting, and how do you endeavor to capture the essence of the book despite the limitations of moviemaking?

I spend a lot of my time as a screenwriter hating the novelist. I’ve always admired screenwriting, but I’ve got a newfound respect for how difficult it is. Especially adaptation; trying to turn a full-length novel into a 110-page screenplay without slash-and-burning is murder.

That’s not to say I’m not enjoying it. I am, immensely. It’s fun to have new colors on the palette and a differently shaped canvas. There are things you can do in a movie that just wouldn’t sell in a book—ways to play to the visual, for example, or moments when you’re providing something for an actor to embellish upon.

What I hope to do, what I’m trying to do, is to take this thing that I spent 18 months sweating over, look at it with fresh eyes, reduce it to central truths, and then rebuild it—leaner, tighter, different but the same.

I hope it works. If it doesn’t, I can’t blame the screenwriter this time.

To learn more or order a copy, visit:

Marcus Sakey’s books have sold more than a million copies and been translated into dozens of languages. He lives in Chicago with his wife and daughter. For more information, visit MarcusSakey.com and follow him on Facebook and Twitter.