“Write what you know” is such common advice for new writers that it has become a cliché. It sounds seductively simple: you just look at the life you’re living and the people you see and write a story about them. No need to imagine fantasy worlds or recreate life on a distant planet or in a dystopian future; no need to research a historical period and hope you get the details right. Everything you need is right there in front of you.

Right.

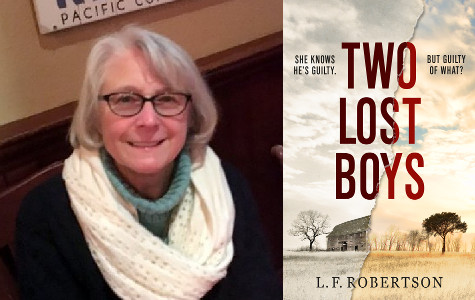

When I wrote my first novel, Two Lost Boys, I decided to write about what I do for a living—something I know that is unusual enough to supply material for a mystery novel. I work in death penalty defense not as a trial lawyer but on the appeals of people who have already been convicted and sent to death row. In real life, though, my work is mostly a lot of research and writing, going out to visit my clients and the people who knew them, and more research and writing. It also involves a lot of obscure law and technical legal procedures. My cases go on for a very, very long time, with a pronounced lack of exciting courtroom scenes and explosive denouements.

So I faced the challenge of turning a job that largely consists of sitting at a computer into the framework for a story. I compressed what would have been several years of work in the real world into a year and a half by creating a short deadline and introducing my main lawyer character into the case late so that most of her investigation into the facts of the case could be done in that time frame. As a basically honest person, I was a bit uncomfortable with my tinkering with reality, and I couldn’t help thinking that if I had set my story on an exoplanet colony a few hundred years into the future, this would not have been an issue.

Then there were characters. Whatever period or universe you’re writing in, you get to just make them up—although you also have to make them credible. But when you’re writing from your own life—unless you intend to write a roman a clef—you need to think hard about who might see themselves, or think they do, in your book. As a lawyer, I have to be careful about people’s secrets, so I had to make my story somewhat different from any real case I knew about and create characters who weren’t quite the same as people I had met. If I’d written a mystery set among the upper classes in Regency England, I’d have had no worries on this score.

In writing Two Lost Boys, I wrote what I knew because I had some things I wanted to say about the death penalty and the criminal justice system in contemporary America. But I think it’s a mistake to believe it’s just easier to write fiction based on your own experience. I’ve written short stories set in other times and places: the Arctic at the turn of the last century, the California of Robert Louis Stevenson and The Silverado Squatters. I had a wonderful time researching and writing them, and I didn’t have to worry that they would invade anyone’s privacy, mislead the public, or be too much like recent events.

I guess if there’s a point hidden in all this, it’s that writing fiction, wherever you start, is hard work, and using your own experiences as material doesn’t necessarily get you out of it.

Read an excerpt from Two Lost Boys, and then check out Kristin Centorcelli's review!

To learn more or order a copy, visit:

L. F. Robertson is a practising defense attorney who for the last two decades has handled only death penalty appeals. Linda is the co-author of The Complete Idiots Guide to Unsolved Mysteries, and a contributor to the forensic handbooks How to Try a Murder and Irrefutable Evidence. She has had short stories published in the anthologies My Sherlock Holmes, Sherlock Holmes: the Hidden Years and Sherlock Holmes: The American Years.

Thanks