“Coming Close to Donna,” “Que Vadis Smut?,” “Midnight and I’m Not Famous Yet,” and “Green Gets It” are all stories within Barry Hannah’s Airships that walk the fine line between noir and literary fiction. These deeply flawed and incredibly human characters are great examples of psychological noir and this is especially true for Quarles Green from Hannah’s story “Green Gets It.” What makes Quarles so impressive is the fact that he doesn’t need to fully act on his depraved impulses in order to represent the genre. No, Quarles is at war with his own life, his own thoughts. He’s so miserable in his passivity toward life that he flings himself into the Hudson River (a failed suicide attempt), leaving behind a note which only echoes bitterness toward his family:

My Beloved Daughter,

Thanks to you for being one of the few who never blamed me for your petty, cheerless and malign personality. But perhaps you were too busy being awful to ever think of the cause. I hear you take self-defense classes now. Don’t you understand nobody could take anything from you without leaving you richer? If I thought rape would change you, I’d hire a randy cad myself. I leave a few dollars to your husband. Bother him about them and suffer the curse of this old pair of eyes spying blind at the minnows in the Hudson.

Your Dad,

Crabfood

Quarles feels dread at the very notion of having to live in a misery of his own making. The best psychological noir stories don’t gain their tension from physical violence; they get their tension when a character’s psyche is threatened, when their hopes, dreams and desires are all but lost.

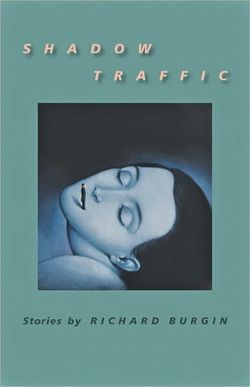

Richard Burgin’s collection Shadow Traffic is a shockingly splendid example of psychological noir. I’m a long-time fan of Burgin’s writing, and I can honestly say that there are few people whose short stories I admire more. In my opinion, no contemporary writer of the short story creates better characters than Richard Burgin. In Shadow Traffic, Burgin manages to cram a novel’s-worth of character into each of these twelve tightly-woven stories, giving us unforgettable character psyches that defy simple classification.

In “The Dolphin” Parker tries to blow off steam at a strip club, but is instead confronted with Nick’s lustful revenge directed at Trudy, a stripper performing on-stage. The story unfolds in a tense monologue, eerily echoing the homicidal, yet impotent rage that Martin Scorsese ushered forth in his cameo appearance in the back of Robert De Niro’s cab in Taxi Driver. Unhinged by life, or more precisely the dread of living a hopeless existence, Nick turns his rage inward, telling Parker:

You think I’m a regular flesh and blood person like you are? Or maybe you think I’m a vampire ’cause I’m dressed in black. I don’t want her whore’s blood if that’s what you think. I don’t need anyone’s blood to live. I’m wearing black ’cause I figure I’m already dead. Yah man, you confused me with the living but I’m actually dead. Death is really different. Only thing is, they don’t tell you that you get lonely when you die. Yah, that’s why I’m gonna take her with me. It’ll solve my loneliness problem real fast.

Nick’s private world crashes head-long into Parker’s public life, breaking the latter’s ennui. Burgin’s characters in “The Dolphin” vividly illustrate the modern human condition of passivity. We all enjoy talking about and imaging the dark things we’d like to do to someone who has wronged us, and these dark thoughts form a rich soil for noir to thrive in.

This concept of passivity is beautifully conceptualized in “Caesar” when Malcolm discovers that his actions are rendered impotent by the constraints of civilized society. He’s forced to pick up men. But when he fails to charm them, Malcolm finds himself dumped and left at the mercy of being picked up by a sexual predator, the much older and more sophisticated Gene, whose erotic preferences run toward the macabre. Gene thrives in this upper-class world, unlike the socially awkward Malcolm, who insists on being called by his middle name, Caesar. But Malcolm is no Caesar when he is cornered by Gene:

There were pictures of hooded men in chains doing forbidden things to their master, who was holding a whip and who was masked in some photographs, although it soon became apparent in others that it was Gene or a younger version of him. In still others, the slaves were dressed like children, and were attempting to simulate their size by being photographed on their knees. Malcolm stared at the pictures, frightened and appalled. Then the photographs began to feel like little snakes in his hands, but he forced himself to handle them and not say anything, told himself the drugs were causing it and that Gene mustn’t know how stoned he was.

“What’s it like looking at the future, little boy?”

Burgin uses Malcolm’s inability to stand up for himself, his failure to self-actualize his needs and desires, to show how the world can castrate our hopes and dreams, leaving us in a constant state of dread, fearing not death but of living a life without any meaning. Yet Burgin also has a great sympathy for his characters and leaves us with a sense of hope for Malcolm. At the end of “Caesar” Malcolm pauses in his flight from Gene and chooses to rescue an old woman who has fallen in the snow. For a brief, flickering instant, Malcolm is able perform an action that allows him to live up to his nickname.

Reading each story in Shadow Traffic is a dark thrill, a head-first dive into dangerous waters of psychological noir. The characters may be pounded into passivity by life, but there isn’t a single character that remains static, not one throwaway scene in this collection. Be on the lookout for more of Burgin’s excellent noir work in the forthcoming anthology New Jersey Noir, edited by Joyce Carol Oates.

Marc Watkins lives in Oxford, Mississippi. He has published or had work recently accepted for publication in The Pushcart Prize XXXV (2011), Poets & Writers, StoryQuarterly, Texas Review, Third Coast and Boulevard. He recently served as a guest fiction editor for Pushcart Prize XXXVI (2012).