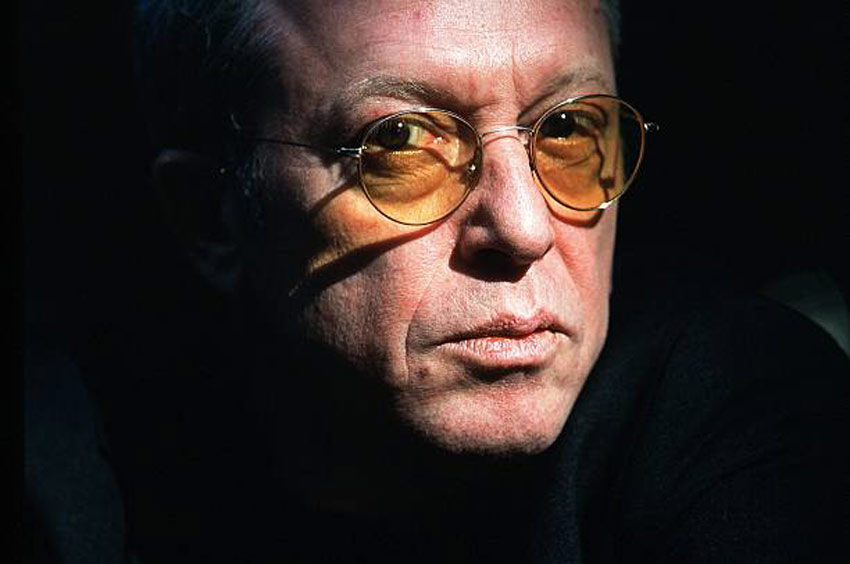

Pascal Garnier: A Glimpse at the Man Behind the Books

By Brian Greene

There’s good news for English-speaking noir fiction enthusiasts who are late to the party in getting hip to Gallic/Belgravia Books’ series of English-translation versions of the novels by Frenchman Pascal Garnier (1949-2010). Gallic/Belgravia is now re-issuing Garnier’s edgy suspense tales in omnibus editions. Gallic Noir Volume 1, which was released in the U.S. on April 3rd, contains three of Garnier’s finest noir works: The A26 (originally published in French in 1999), How’s the Pain? (2006), and The Panda Theory (2008). Gallic Noir volumes two and three are set for release in June and September, respectively. A fourth volume is being planned for publication in January of 2019.

Garnier, whose literary style has often been compared to that of suspense-fiction master Georges Simenon, wrote in an easy, approachable tone that makes his readers comfortable and sets them up for brainfucks when all manner of existential mayhem starts erupting among his quirky characters. The people in his twisted stories are an enjoyable oddball bunch, and their life events told across the pages of the books are unexpected and compelling. And the brief, waste-free novels are sprinkled with surprising, offhanded yet brain-dazzling, philosophical observations Garnier’s narrators drop here and there over the courses of the tales.

But what about the character of Garnier himself? He remains an enigmatic figure to this point. On the website for Gallic/Belgravia, there’s an “in his own words” autobiographical sketch the author wrote for his French publisher, Zulma. That brief overview of his life is elusive yet informative and is told in the knowingly world-weary yet playful way Garnier often wrote in his noir novels. It’s the kind of thing that tells you a little about the man while filling your head with new questions about him.

The author’s daughter, Eve Garnier (born 1972), is a Montreal-based performance artist who works in dance and theater. Eve describes her father’s childhood as a somewhat typical French working-class familial experience for the times. His parents seem to have been no-nonsense middle-class Parisian citizens who believed in putting in a good day’s work but who were not terribly in touch with their emotions. Eve says that it bothered Pascal that his parents never openly complained about the German invasion and occupation of France during World War Two. Hearing her talk about that immediately makes one think of one of the main characters in her father’s novel The A26: an insane woman who, in the early 1990s, hasn’t left her family’s home since the Germans invaded it and believes they’re still lurking around her neighborhood.

Eve tells, “When I read his books, I see that his mind was formed by observing people who couldn’t really talk to each other, and what happened between them when things blew up.”

Pascal and Eve’s mother split up when Eve was two. She was raised mostly by her mother. Pascal, who dropped out of school as a teenager and left home to travel the world, was a rock and roller in the ‘70s. Eve says that—at least in the early part of his adult years—he was the kind of guy who, when confronted with life problems, tended to pack up his few personal belongings and move on rather than attempt to confront the difficulties.

“To get out of a situation you don’t want to be in any longer, you just leave it,” is how she explains her father’s mindset from this era of his life. “And you take with you not memories of what actually happened in the situation you’re leaving, but memories you make up.”

Eve describes their father-daughter relationship as being somewhat removed from a traditional one, and she says she felt Pascal experienced parental anxiety and perhaps a sense of failure as a father figure. But the two grew closer in later years, primarily via written correspondence. And although Pascal was not particularly interested in Eve’s chosen forms of artistic expression, she says he was able to empathize and offer advice and support as she made her way in this area of life.

“When I was a child, he didn’t really ask me questions about me,” she explains, “but he asked me about my dreams.” She has fond memories of when Pascal took her to cafés and they engaged in people watching and discussed those they viewed. “We looked at other people and then invented stories about what their lives were like. I loved that.”

Pascal met his second wife, Nathalie Ange-Garnier, in 1997. The occasion was a festival celebrating the black (dark) novel in Valence, Drôme. Pascal was an invited guest author, and Nathalie was a volunteer. Nathalie, 17 years Pascal’s junior in age, says it was love at first sight. They remained together until Pascal died from cancer 13 years later.

“Because it was him, because it was me, because it was the right moment,” Nathalie explains when asked what drew the pair together. And as for what kept their bond growing, she adds, “Together we were free. (We shared) black humor, literature such as Georges Simenon, Emmanuel Bove, and Chester Himes, a certain despair and yet a glimmer of hope, a shared vision of the world, a common madness … We thank life for allowing us to meet and love each other.”

Pascal and Nathalie were together during the years when many of Pascal’s noir novels were written and published. Asked about his outlook when it came to his writing, she answers, “He was aware of his talent, but obviously he doubted himself, more and more—after finishing a book, beginning a new one, at the turning point of a story. But he was always proud to receive a finished book and to take the object into his hands. It was a kind of reparation for him leaving school at age 15, and when it came to his parents, as he was the only one of their three children who did not have a ‘real’ job.”

The odd and often bizarre sets of characters and predicaments in Garnier’s novels lead one to wonder from where he drew his inspiration. Besides the previously mentioned batshit-crazy female character from The A26, that story also involves the woman’s brother: a meek kind of man who has always catered to his overbearing sister but who, now that he has a terminal illness, is ready to act out. How’s the Pain? involves a hitman who has decided to end his own life and enlists a likable and gullible young man to aid him in his death-wish plan. The Panda Theory revolves around a seemingly happy-go-lucky but oddly displaced and aloof guy who drifts into a seaside town and starts getting involved in the lives of some of the locals. Garnier’s other noir novels are rich with singular characters and intriguing situations as well.

The odd and often bizarre sets of characters and predicaments in Garnier’s novels lead one to wonder from where he drew his inspiration. Besides the previously mentioned batshit-crazy female character from The A26, that story also involves the woman’s brother: a meek kind of man who has always catered to his overbearing sister but who, now that he has a terminal illness, is ready to act out. How’s the Pain? involves a hitman who has decided to end his own life and enlists a likable and gullible young man to aid him in his death-wish plan. The Panda Theory revolves around a seemingly happy-go-lucky but oddly displaced and aloof guy who drifts into a seaside town and starts getting involved in the lives of some of the locals. Garnier’s other noir novels are rich with singular characters and intriguing situations as well.

Nathalie points out that Pascal got ideas for his novels in a variety of ways—everything from something he heard on a radio documentary to a photo taken by a friend to news articles that caught his attention.

She says his friends often lent their names to his characters without their personalities being tied to the fictional people. Asked if she sees any of her late husband himself in those who populate his books, she says yes, “in his distance from the world, elegance, and humor.”

Eve Garnier mentions something interesting about the characters in her father’s books. Pascal was a visual artist in addition to his efforts as a writer. He was a painter whose work was shown in gallery exhibits. And he liked to sketch, often giving drawings he’d done as gifts to friends. Eve says he often drew while riding trains on occasions such as when he traveled to give writing workshops to students (something she says he loved doing). Eve shares that Pascal sometimes drew people in his sketchbooks during these railway treks and that, at times, those figures in his drawings became the characters in his books.

His characters relocating is a common theme among Garnier’s novels. Whether it’s a permanent move from one locale to another or just an extended visit, he liked to shift the people in his books from one setting to another and see what became of them as a result of the move when they were faced with especially challenging existential problems during or just after the transition. In particular, he had a penchant for writing about French city-people who packed up and headed to the provinces. And this makes sense, as the author himself spent the last era of his life in a small, quiet French village after residing in Paris and then Lyon. Both Nathalie (who lived with him through this time) and Eve say that Pascal eventually adapted to the rural life and that he enjoyed the extra space for his writing and visual-art activities. If only his characters got used to the rustic life so easily … oh, but then we wouldn’t have these wonderfully bent novels.

So we can now see a little into the people in Pascal Garnier’s books. But what about the writer and how he conducted himself in day-to-day life? When asked about Pascal’s temperament and his general behaviors, Eve and Nathalie present different sides of a man who, again, seems to have been the kind of guy who, when you got to know him a little, you just had more questions about him.

“You know how, at a party, there is often one person who is surrounded by others?” Eve relates. “That was him. People were drawn to him. He got people to talk about themselves to him. But he didn’t tell them about himself.”

Nathalie states that her late husband was a man who would take up a cause if it meant something to him personally, but that he preferred not to belong to groups or associations. She elaborates more on his character as she saw him:

“He didn’t like how the world was changing—the speed of the world, the violence of the world of work in particular. The philosopher Paul Virilio inspired him. I always knew him with a rather dark vision, even desperate, but with infinite tenderness for his contemporaries, big and small. He never forgot the child he was.”

One striking aspect of Garnier’s noir novels, at least to this reader, is that they are ripe for film adaptation. All three of the titles in Gallic Noir Vol. 1 are begging to be adapted to the big screen, and the same is true of other fictional works by Garnier—especially The Front Seat Passenger. It seems Eve Garnier and Nathalie Ange-Garnier feel this way as well. To date, there has been the odd French TV production of his work but no full-length feature films.

Noir-oriented movie producers/directors, what are you waiting for?

Comments are closed.

weep holes