Page to Screen: The Parallax View

By Brian Greene

January 21, 2021

The early-to-mid 1970s was a time when Americans’ distrust in our politicians was at a peak. The country still had not gotten over the 1960s assassinations of beloved young leaders John F. and Bobby Kennedy, and Martin Luther King, Jr. Many still wondered whether the individuals held responsible for their killings acted alone, or were scapegoated patsies hired by government officials or other politically influential groups who felt threatened by their agendas and the adulation they inspired in much of the public. If all of that wasn’t enough to make Americans paranoid about the dastardly lengths to which our elected leaders might stoop in order to serve their special interests, we had Watergate in the early ‘70s.

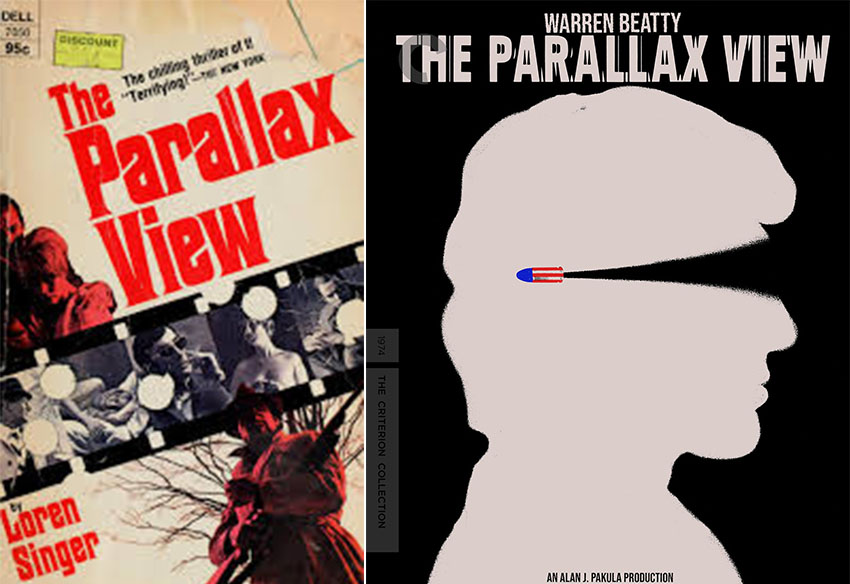

One day before the publication of Bob Woodward’s and Carl Bernstein’s 1974 Watergate expose book All The President’s Men, a film about frightening doings involving political assassinations opened in movie theaters. Based on a 1970 novel by an obscure author, and directed by the same man who would adapt All the President’s Men for the big screen in ’76, The Parallax View took all of that suspiciousness and wariness many felt about secret government dirty deeds and channeled it into a major motion picture. With the Criterion Collection set to release a new version of The Parallax View in early February (and with distrust in our political leadership having reached another peak over the past four years), now’s a great time to revisit the movie, as well as the book that served as its basis.

Let’s start with a discussion of the novel. It was the debut work of published fiction by Loren Singer (1923-2009), a guy who had learned some things about covert government operations while serving in the U.S. Army in the ‘40s, and who at the time of the novel’s publication worked at his father-in-law’s printing business while doing some writing for TV in his spare time.

Singer’s omniscient narrator tells the story in a purposefully vague way. We get very little detail and just have to take the events at face value, without understanding much about the background behind the actions of the characters. All we know initially is that out of eight New York City-based members of the press who stood together and witnessed some kind of spectacle, four have recently died under suspicious circumstances. Two of the remaining four, certain of foul play existing behind the demise of their former colleagues, start investigating their deaths. Their research leads them to a nondescript company called Parallax, which is based in Washington, D.C. and which appears to use cryptically worded advertisements to recruit assassins. The tension in the story, which is acute from the first page, kicks into another gear when these two—a journalist named Graham and a photographer named Tucker—answer Parallax ads under pseudonyms and get themselves invited for interviews, wanting to get inside the strange and apparently sinister organization and understand its doings.

The Parallax View is a peculiar novel. Singer was successful in his efforts to create a paranoia-inducing thriller. And some of the scenes, filled with quiet but lethal menace, are written expertly. Yet in the end it’s an often frustrating, ultimately unsatisfying read. Singer didn’t bother to try to make us see Graham, Tucker, or other characters physically or in terms of understanding their life stories and motivations. Maybe this was a purposeful omission, because he thought the anonymity in the characters was right for the novel. But it can be hard to care, one way or the other, about characters you don’t feel you can visualize or understand. And the same goes for the details of the story. We’re three quarters into the novel before we even begin to (kind of) get why some association of powerful and evil people felt these witnesses needed to die, or to have a glimpse into the makeup of that association. There’s much to be said for only gradually revealing pertinent details in a suspense novel, but Singer went too far in this way and in so doing made the tale more murky than intriguing. Additionally, even while being too minimalistic in the above-mentioned ways, the novel is riddled with lengthy, annoying tangents that don’t add anything worthwhile to the story.

Singer wrote a few more scattered novels later in his life. He never gained much lasting recognition as a fiction writer. But his debut, flawed though it is, was a timely work and one that got made into a highly notable feature film which was put together by, and acted in, by some of the biggest cinematic names of the 1970s.

The film version of The Parallax View was the fourth directorial effort by Alan J. Pakula (1928-98). It was the middle piece of what became known as Pakula’s “paranoid trilogy,” the other titles being Klute (’71) and the afore-mentioned All The President’s Men. Singer’s novel was adapted for the screen by the writing team of David Giler and Lorenzo Semple, Jr., and was rewritten several times. Screenwriting master Robert Towne added some late rewrites to the script, in an uncredited capacity. Pakula said of the film that it represented his fears at the time, and that when it played in movie houses, it was successful in realizing its intentions if it left viewers a little less comfortable about the person they’d sat next to in the theater.

The film is much more transparent than the novel, in the way of making the plot understandable. In the opening scene, a rising U.S. Senator, who seems to be an independent-minded maverick, is assassinated by a man posing as a waiter at a Fourth of July publicity event at Seattle’s Space Needle. In the next scene, a Warren Commission-like body coldly announces to the public that after months of investigating the murder, they have concluded that the killer was an attention-seeking psychopath who acted totally alone, and they implore the media to stop speculating about the assassination possibly having been orchestrated by a group of conspirators. Is this sounding familiar?

Warren Beatty portrays Joe Frady, an Oregon-based, longhaired, hot-tempered, hunky investigative newspaper reporter who was at the Space Needle when the assassination occurred. It’s three years later, and Frady is visited by a roving reporter, played by Paula Prentiss, who is an ex of Frady’s and who was also on the scene when the senator was murdered. Haunted and terrified, she points out to Frady that six others who were witness to the killing have recently died under dubious circumstances. She fears she may be next, and she begs Frady to work with her in investigating the deaths of the others. Frady blows her and her suspicions off, but when she dies shortly after their meeting, he changes course. He develops a couple different fake identities and starts looking into some of the assassination witnesses’ deaths.

Just as happened with Graham and Tucker in Singer’s novel, Frady’s probing into the suspicious passing of the other Space Needle tragedy witnesses leads him to a strange outfit called The Parallax Corporation. Frady comes to understand that Parallax is in the business of finding, recruiting, and training the kinds of unattached loose cannons who are likely to be easily molded into killers for hire. And, also as happens with the novel characters, Frady assumes a false identity and insinuates himself into Parallax’s world by passing himself off as a candidate to become one of their paid murderers.

Let’s leave the movie’s plot right there. It’s been written in other places that the script of The Parallax View film is a complete departure from the text of Loren Singer’s novel. That’s not entirely accurate. While the movie does contain scenes, and characters, not present in the book, the basics of the story are the same in both versions. It’s just that Pakula and the screenwriters took the best parts of Singer’s book—the tension, and the terrifyingly sinister activities of Parallax—and used those foundations to develop a compelling, vivid story one can follow and that is peopled with relatable characters you can love, hate, or feel indifferent to, but who come to life for you in a way that makes you care about what happens to them. Beatty, Prentiss, Hume Cronyn (he plays Frady’s editor at the newspaper), and the other actors also deserve much credit, for fleshing out the characters via outstanding performances that made Pakula’s film a great artistic achievement.

Not all critics loved The Parallax View when it hit theaters in 1974. Roger Ebert gave it four out of five stars and had some complimentary things to say about it, yet thought Beatty’s character was too one-dimensional. Vincent Canby compared Pakula’s work unfavorably to what a Hitchcock might have been able to do in adapting such a story into a motion picture. Other notable critics heaped an assortment of praise and critical abuse on the film. Despite some of the experts’ problems with it, The Parallax View won a major prize at a film festival in France and was nominated for a Best Motion Picture Edgar award. Recent appraisals from influential critics have been more clearly and consistently favorable.

For me, The Parallax View movie is a flawless political thriller that perfectly harnesses and evocatively illustrates the fear, pessimism, and distrust the King and Kennedys’ assassinations implanted so deeply into people’s psyches and hearts. And the montage scene, when Frady’s in Parallax’s testing room? No need for me to describe that—you just need to see it, if you haven’t already. If I’d been of an age in 1974 where I’d gone to see the film on the big screen, I could’ve told Pakula that, yes, after the final credits rolled and we all started shuffling out of the theater, I found myself looking nervously askance at the other people around me.

Criterion’s edition of The Parallax View comes with a slew of bonus features that add depth to one’s understanding and appreciation of the movie.

Check out Criterion’s edition of The Parallax View.

Comments are closed.

We just watched this and Klute both recently. It’s a fascinating film, and I appreciated this extra information on the novel behind it!

Such sites are important because they provide a large dose of useful information. This is very significant, and yet necessary towards for me. Thank u!

Such websites are crucial since they include a wealth of relevant information. This is incredibly important and yet required for me. Thank you very much!