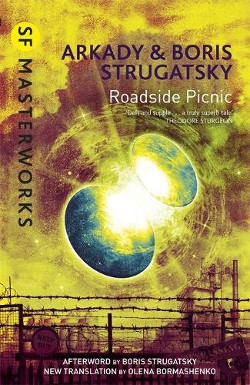

Some admirers of the science fiction novel Roadside Picnic, written by the brothers Arkady and Boris Strugatsky, might feel that the book has not received the critical and popular recognition it deserves, particularly in comparison to the film that was made from it: Andrei Tarkovsky’s widely celebrated Stalker (1979). But really, those of us who appreciate the novel should be thankful that we are aware of it at all.

Completed by the Russian brothers in 1971 and published in a magazine the following year, it was held up in book form for several years due to Soviet censorship. And when the authorities of the Strugatsky brothers’ home country did finally see fit to allow the story to appear as a book, it came out in a heavily censored version. However, the novel finally saw its release in its original form—in scores of different languages—and for this, we can be grateful. Criterion Collection’s new edition of the Tarkovsky film provides an opportunity for a fresh look at both novel and movie.

The premise of the novel is fertile. A mysterious alien force visited various parts of the earth and then vanished, never having been seen by any humans. But whoever or whatever they were, they left behind six areas, called “zones,” that are filled with substances, objects, and phenomena that are both fascinating and dangerous. When people start entering these zones, it quickly becomes apparent how perilous they are, as many visitors either die or become afflicted in some horrific way by exposure to the elements the aliens planted.

The premise of the novel is fertile. A mysterious alien force visited various parts of the earth and then vanished, never having been seen by any humans. But whoever or whatever they were, they left behind six areas, called “zones,” that are filled with substances, objects, and phenomena that are both fascinating and dangerous. When people start entering these zones, it quickly becomes apparent how perilous they are, as many visitors either die or become afflicted in some horrific way by exposure to the elements the aliens planted.

The zones get cordoned off by the authorities, and it becomes illegal to go into them. But, of course, people want to get in there and come back out with some of the odd objects to be found inside, whether just out of blanket fascination, the belief that what’s in the zones have properties that could lead to fascinating study, to make themselves famous, or to get deep pockets by selling the zone loot to bidders willing to pay big bank for the stuff.

There comes to be a type of person known as a “stalker” who is a daredevil/badass who becomes a kind of expert at navigating the zones. Stalkers enter the post-apocalyptic areas either on their own, to go in and haul out booty they can sell on the black market outside, or as paid guides to fellow travelers who dare to enter the zones but are only willing to do so in the company of knowing chaperones. But all who enter, including the stalkers, plunge into the zones at their own grave risk. They could be killed by some material or force found inside, they might lose a limb, or they might be exposed in such a way that there is a good chance that they will develop afflictions later—including the danger that any children they have later will be deformed in some way.

Roadside Picnic is set in one particular zone in the fictional Canadian city of Harmont, and it focuses on the doings of one particular stalker: Redrick “Red” Schuhart. I could get lost describing more of the plot, but it’s better that I stop doing that now. It’s a hell of a read. Any fan of edgy sci-fi who enjoys the output of the likes of Philip K. Dick, J. G. Ballard, or the Strugatsky brothers’ countryman Stanislaw Lem will likely go for the book. But you don’t have to be a sci-fi head to come under its spell. The novel is written in a lean, hard, no-nonsense way that is likely to be enjoyed by noir enthusiasts as well.

Tarkovsky worked from the original version of the novel, having read it when it appeared that way in a magazine. Despite this, and despite the fact that the Strugatsky brothers contributed the screenplay to Stalker, the film is vastly different from the novel in some essential ways.

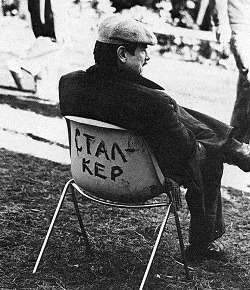

The production of Stalker was a drawn out and, by various accounts, painful and hazardous movie to shoot. The entire original version that the Russian auteur shot was found to be unusable due to the poor quality of the film as well as the inferior manner in which it was developed. The original cinematographer was canned, a new one was hired, and they started over with a new location. The known version of the movie was filmed in Estonia in locales such as power plants and chemical factories, and there are those who believe that exposure to the hazardous matter in those areas contributed to Tarkovsky’s death from lung cancer at age 54 (1986).

While the basic setup of the film is similar to that of the book, Tarkovksy made key departures from the novel. His movie features one particular stalker, and that man comes across as a different kind of guy than Red Schuhart—less talkative, less rough and tumble, moodier, and more vulnerable. While Roadside Picnic takes us through several visits to the zone by Red and various others, the movie revolves around just one entry into the magical/hazardous area.

The novel is relatively brief, moves at a brisk pace, and is largely told via actions and crisp dialogue. Tarkovsky’s version, meanwhile, is a slow (161 minutes), meditative, atmospheric work that relies on long shots and philosophical conversations between characters.

The movie’s stalker has two guests in the zone: a writer and a science professor, each of whom has his own reasons for wanting to take the enormous risk of traversing the lethal area. It’s the brainy chats between these two guys more than their experiences inside the zone that tell the story the way Tarkovsky wanted it told.

The film is shot beautifully. But at the risk of offending some of Stalker’s admirers, I will confess to finding the discussions between the characters to be often tedious. Because of this, as well as the mesmerizing look of the movie, I think Stalker is best enjoyed with the volume and subtitles shut off.

See also: Page to Screen: Thieves Like Us & They Live by Night

Brian Greene writes short stories, personal essays, and reviews and articles of/on books, music, and film. His work has appeared in 25+ publications since 2008. His pieces on crime fiction have also been published by Noir Originals, Crime Time, Paperback Parade, The Life Sentence, Stark House Press, and Mulholland Books. Brian lives in Durham, North Carolina.

His writing blog can be found at: http://briangreenewriter.blogspot.com. Follow Brian on Twitter @greenes_circles

Stanislaw Lem was Polish, not Russian, but hell, small difference. Nice article, though.

oh no, forget that. Watch this movie without the dialogue?? Maybe the author ought to learn to think a bit more.

Also, 107 women were attacked with acid, 1,580 women were trafficked, 15 girls were sold and 2,668 women were victims of cybercrimes.