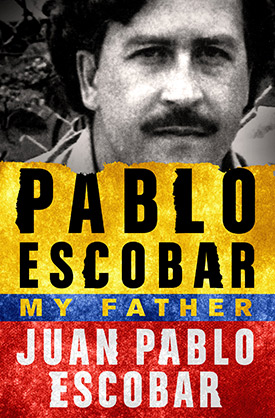

Until now, we believed that everything had been said about the rise and fall of Pablo Escobar, the most infamous drug kingpin of all time, but these versions have always been told from the outside, never from the intimacy of his own home.

More than two decades after the full-fledged manhunt finally caught up with the king of cocaine, Juan Pablo Escobar travels to the past to reveal an unabridged version of his father—a man capable of committing the most extreme acts of cruelty while simultaneously professing infinite love for his family.

This is not the story of a child seeking redemption for his father, but a shocking look at the consequences of violence and the overwhelming need for peace and forgiveness.

1

Betrayal

In the Residencias Tequendama apartment hotel on December 3, 1993, after the trip to bury my father in Medellín, our firm intention was to live as normal a life as circumstances allowed. For my mother, my sister Manuela, and me, the past twenty-four hours had been the most dramatic of our lives. Not only did we have to endure the agonizing pain of losing the head of the family in such a violent manner, but the funeral had been even more traumatic.

A few hours after Ana Montes, the national director of the attorney general’s office, personally confirmed to us that my father had died, we had called the Campos de Paz cemetery in Medellín. They refused to perform the funeral service, and we might have had a similar experience with Jardines de Montesacro, except that relatives of our lawyer at the time, Francisco Fernández, owned the cemetery. My grandmother Hermilda had two lots there, and we decided to use them to bury my father and Álvaro de Jesús Agudelo, known as “Lemon,” the bodyguard who was with him when he died.

After assessing the risks of attending the funeral, for the first time we defied one of my father’s old orders: “When I die, don’t go to the funeral; something could happen to you there.” He’d insisted that we shouldn’t bring him flowers or visit his grave either. But my mother said she’d go to Medellín “against Pablo’s wishes.”

“Well, then we’ll all go, and if they kill us, so be it,” I said, and we rented a small plane to travel to Medellín with two bodyguards assigned by the attorney general’s office.

After landing at Olaya Herrera Airport and being besieged by dozens of journalists, who even risked their lives by swarming onto the runway while the plane was still moving, Manuela and my mother were ushered into a red SUV and my girlfriend Andrea and I into a black one.

When we arrived at Jardines de Montesacro, I was pleasantly surprised to see how many people had shown up for the funeral. It was a testament to the love that the lower classes felt for my father, and I was touched to hear the same chant they used when he would inaugurate athletic fields or health clinics in poor areas: “Pablo! Pablo! Pablo!”

In an instant, dozens of people surrounded our SUV and began pounding on it as we headed to the site where my father was to be buried. One of the bodyguards asked if I was planning to get out, but since I knew that we might be in danger, we retreated to the cemetery’s office to wait for my mother and sister. I remembered my father’s warning and decided the wisest move was to take a step back.

A few minutes after we entered the office, a secretary came in, panicked and in tears. Someone had just called to announce an attack. We ran out of there and got into the black SUV again, where we stayed until the funeral was over. I was right there, just thirty yards away, but I couldn’t attend the service, couldn’t say good-bye to my father.

* * *

On December 19, 1993, two weeks after my father’s death, we received a call from Medellín: an assassination attempt had been made on my uncle Roberto Escobar in the Itagüí maximum-security prison.

At the time we were still sequestered under heavy guard on the twenty-ninth floor of Residencias Tequendama in Bogotá. Worried, we tried to find out what had happened, but nobody could tell us anything. The television news reported that Roberto had opened an envelope from the Office of the Inspector General and it had exploded, resulting in serious injuries to his eyes and abdomen. The next day, my aunts called and told us that the Clínica Las Vegas, where he’d been taken for emergency treatment, lacked the ophthalmology equipment needed to operate. And as if that weren’t enough, there were also rumors that an armed commando was planning to finish him off in his sickbed.

My family decided to move Roberto to the central military hospital in Bogotá, which not only was better equipped but also offered security. My mother paid three thousand dollars to rent an ambulance plane, and once we’d confirmed that Roberto had arrived at the hospital, we decided to visit him with my uncle Fernando, my mother’s brother.

As we left the hotel, we were unnerved to discover that the agents from the Technical Investigation Corps (CTI), the division of the attorney general’s office that had been protecting us since late November, had been replaced that day, without previous notice, by agents from SIJIN, the police’s criminal investigation unit. I didn’t say anything to my uncle, but I sensed that something bad was about to happen. In other areas of the building, managing other aspects of our security, were agents from the Central Directorate of the Judicial Police and Intelligence (DIJIN) and the Administrative Department of Security (DAS). Outside, the Colombian army was responsible for our safety.

A couple of hours after we arrived at the hospital, a doctor requested authorization from one of Roberto’s family members to remove both of his eyes, which had been badly damaged in the explosion. We refused to sign and asked the specialist to do whatever he could to preserve Roberto’s sight, no matter the cost, even if the chances of success were vanishingly small. We even offered to fly in the best ophthalmologist from wherever he might be located.

Hours later, not yet conscious, Roberto came out of surgery and was moved to a room where a guard from the National Penitentiary and Prison Institute was on duty. Roberto’s face, abdomen, and left hand were bandaged.

We waited patiently until he began to wake up. Still groggy from the sedation, he said he could see shades of light and darkness but was unable to make out shapes.

When I saw he’d recovered a bit, I told him I was feeling anxious. If they’d made an attempt on Roberto’s life after my father’s death, then my mother, my sister, and I were surely next. I desperately asked him if my father had a helicopter hidden somewhere that we might be able to use to make an escape. Over the course of our conversation, which was frequently interrupted by nurses and doctors making their rounds, I repeatedly asked Roberto what we could do to survive the threat posed by my father’s enemies.

He was silent for a few moments and then instructed me to grab a pencil and paper.

“Write this down, Juan Pablo: ‘AAA.’ Take it to the U.S. embassy. Ask them for help, and tell them I sent you.”

As I put the paper in my pocket, Roberto’s surgeon entered and informed us he was optimistic, that he’d done everything he could to save my uncle’s eyes. We thanked the doctor and motioned to leave, but he told me that I had to stay at the hospital.

“What do you mean? Why?”

“Your security detail hasn’t arrived,” he said.

The doctor’s words made me paranoid because if he’d been in surgery all this time, he had no reason to know what was going on with our security.

“I’m a free man, Doctor. Or am I being detained here?” I said. “In any event, I’m leaving. I think someone’s plotting to kill me today. They switched out the CTI agents who were guarding us.”

“You’re under our protection here, not under arrest. We are responsible for your safety at this military hospital, and we can deliver you only to government security forces,” he said.

“The people who are responsible for my safety out there are the same ones who are coming to kill me,” I insisted. “So you can either help me out by authorizing me to leave the hospital, or I’ll have to make a run for it. I’m not getting in a car with the very people who are after me.”

The doctor must have seen the fear on my face. He quietly agreed to sign the order, and Fernando and I furtively returned to Residencias Tequendama, deciding to visit the embassy the next day.

We got up early and headed to the room where the agents charged with our security were staying. I said hello to the agent known as “A1” and told him we needed an escort to the U.S. embassy.

“Why are you going there?” he demanded to know.

“I don’t have to tell you that. Are you going to give us protection, or do I have to call the attorney general and tell him you’ve refused?” I replied.

“I don’t have enough men to escort you there at the moment,” A1 said, irritated.

“How is that possible, when a twenty-four-hour security detail of some forty government agents and vehicles has been assigned to protect us?”

“You can go if you want, but I’m not going to protect you. And you’ll need to sign a piece of paper waiving our protection,” he said.

“Bring it, and I’ll sign it.”

The agent went into another room to look for something to write on, and we seized the moment to rush downstairs and hail a taxi to the U.S. embassy. It was eight in the morning, and at that hour there was a long line of people waiting to get in so they could apply for an American visa.

I was very nervous as I pushed past the waiting people, explaining that I wasn’t there for a visa. When I reached the booth by the entrance, I took out the paper with the triple A and held it up against the dark, bulletproof glass. In an instant, four muscular men appeared and started to photograph us. I didn’t say a word, and soon one of them approached and instructed me to follow him.

They didn’t ask my name or for ID, didn’t search me or even make me go through the metal detector. Roberto’s triple A was obviously some sort of safe-conduct signal. I was scared. Maybe that’s why it didn’t occur to me to wonder what sort of contact my father’s brother had with the U.S. government.

I was about to take a seat in a waiting room when an older man with nearly white hair and a serious expression appeared. “I’m Joe Toft, director of the DEA for Latin America. Come with me.” He took me to a nearby office and asked me straightaway why I’d come to the embassy.

“I’m here to ask for help because they’re killing my whole family. My uncle Roberto told me to tell you he sent me.”

“My government can’t guarantee you any kind of assistance,” Toft said in a dry, distant tone. “The most I can do is recommend that a judge in the United States assess the possibility of offering you residence in my country in exchange for your cooperation.”

“What sort of cooperation? I’m not legally an adult yet,” I replied, only seventeen at the time.

“You can help us a great deal … with information.”

“Information? About what?”

“About your father’s files.”

“When you killed him, you killed those files.”

“I don’t understand,” said the official.

“The day you collaborated in my father’s death.… His files were in his head, and he’s dead. He stored it all in his memory. The only thing he kept on paper was information about the license plates and addresses of his enemies from the Cali Cartel, and the Colombian police have had those materials for a while now.”

“Well, the judge is the one who decides whether you’ll be allowed to go to the United States, so you’ll have to convince him.”

“Then we have nothing more to discuss, sir. I’m leaving now. Thank you very much,” I told the DEA director, who tersely said good-bye and handed me a business card. “If you remember anything, don’t hesitate to call me.”

I was full of questions as I left the U.S. embassy. My surprising encounter with the head of the DEA in Latin America hadn’t improved our precarious situation, but it had revealed something we hadn’t known before: my uncle Roberto’s high-level contacts with the Americans, the same people who just three weeks earlier had offered five million dollars for my father’s capture, the same ones who’d sent their massive war machine to Colombia to help hunt him.

It was hard for me to believe that my father’s own brother might be working with his number-one enemy. But the possibility gave rise to other doubts, and I soon wondered whether Roberto, the U.S. government, and the Los Pepes vigilante group (named for its members’ shared claim of being “persecuted by Pablo Escobar”) might have formed an alliance to bring my father down. It wasn’t such a crazy theory. It made us reevaluate events we previously hadn’t given much thought.

Back when we’d been in hiding with my father in a country house in the hilly Belén area of Medellín, Roberto’s son, my cousin Nicolás Escobar Urquijo, had been kidnapped. On the afternoon of May 18, 1993, he’d been snatched and taken to the roadside restaurant Catíos between the villages of Caldas and Amagá in the Antioquia region.

We assumed the worst because at the time, in their zeal to find my father, Los Pepes had already attacked a number of family members on both my father’s and my mother’s sides. Fortunately, the scare ended within a few hours. At around ten that night, the kidnappers released Nicolás, unharmed, near Medellín’s InterContinental Hotel.

In hiding, we had less and less contact with the rest of the family, so Nicolás’s kidnapping was eventually forgotten, though my father and I did wonder how he’d gotten out of it alive. In the dynamics of that war between my father and Los Pepes and everyone else who wanted to take him down, a kidnapping was basically a death sentence. How had Nicolás been saved? What had Los Pepes received in exchange for his release only a few hours after abducting him? It seemed likely that Roberto had decided to make a deal with my father’s enemies in exchange for his son’s life.

I got confirmation of that alliance in August 1994, eight months after my visit to the U.S. embassy. My mother, my sister Manuela, Andrea, and I went to see what little remained of our family’s Nápoles estate, which had been left in ruins since my father had gone into hiding. The attorney general’s office had given us permission to go there so my mother could meet with a powerful local drug lord to transfer some of my father’s real estate holdings. On one of those afternoons, as we were walking along the estate’s old landing strip, we received a call from my paternal aunt Alba Marina Escobar, who told us she had to meet with us that night to discuss an urgent matter.

We immediately agreed because in our family, the use of the word “urgent” meant that someone’s life was in danger. She arrived at the estate that same night, without any luggage. We met her in the estate manager’s house, the only building that had survived the ravages of war. The government agents who were guarding us waited outside, and we headed to the dining room, where my aunt ate a bowl of stew. She was going to tell us something only my mother and I could know about.

“I’ve got a message for you from Roberto,” she went on.

“What’s going on?” I inquired anxiously.

“He’s excited because there’s a chance they might give you all visas for the United States.”

“That’s wonderful. How did he manage that?” we asked, and the expression on her face grew serious.

“They’re not going to give them to you right away. There’s something that has to be done first,” she said. Her tone made me uneasy. “It’s simple. Roberto was talking with the DEA, and they asked him a favor in exchange for visas for all of you. All you have to do is write a book about whatever topic you want, as long as the book mentions your father and Vladimiro Montesinos, Fujimori’s head of intelligence services in Peru. Also, in the book you have to say that you saw Fujimori here at the Nápoles estate, talking with your father, and that Montesinos showed up on a plane. It doesn’t matter what’s in the rest of the book.…”

“That’s not actually such good news, Auntie,” I interrupted.

“What do you mean? Don’t you want the visas?”

“It’s one thing for the DEA to ask us to say something that’s true and something I’m comfortable saying, but it’s something else for them to ask me to lie to further their devious ends.”

“Yes, Marina,” my mother broke in, “what they’re asking for is really quite tricky. How are we supposed to justify saying things that aren’t true?”

“Who cares? Don’t you want the visas? You don’t know Montesinos and Fujimori, so what does it matter if you say those things? What you want is to live in peace. These people have sent word that the DEA would be very grateful to you and that nobody would bother you in the United States from that moment on. They’re also offering you the possibility of taking money there with you and using it without any interference from the government.”

“Marina, I don’t want to get myself tangled up in new problems by saying things that aren’t true,” my mother said.

“Poor Roberto, he’s moving heaven and earth to try to help you, and the first opportunity he gets you, the two of you say no.”

In a huff, Alba Marina left Nápoles that night. A few days after that meeting, back in Bogotá, I received a phone call from grandmother Hermilda, who was in New York with Alba Marina. After explaining that she’d traveled there for a bit of sightseeing, she asked me if I wanted her to bring me anything from the city. Naively, without recognizing the significance of the fact that my grandmother was in the United States, I asked her to buy a few bottles of a cologne that weren’t available in Colombia.

Once I hung up, I felt unsettled. How could my grandmother be in the United States less than a year after my father’s death, when as far as I knew the visas of all members of the Escobar and Henao families had been canceled? This was only the latest in a series of events in which my relatives appeared to have murky ties to my father’s enemies. But, distracted by the struggle to merely stay alive, we let time pass without exploring those suspicions further.

Several years later, living in exile in Argentina, we’d be shocked by a TV news report that the president of Peru, Alberto Fujimori, had fled to Japan and sent his resignation by fax. A week prior, Cambio magazine had published an interview in which Roberto claimed that my father had given a million dollars to Fujimori’s first presidential campaign in 1989. He also stated that the money had been sent through Vladimiro Montesinos, who, he said, had visited the Nápoles estate a number of times. My uncle added that Fujimori had promised that when he became president, he would make it easier for my father to traffic drugs out of Peru. At the end of the interview, Roberto noted that he had no proof of any of the allegations he was making because, he claimed, the cartel hadn’t left a trail of its illegal activities.

A few weeks later, Roberto Escobar’s My Brother Pablo hit the bookstores. The 186-page book, published by Quintero Editores, “re-created” my father’s relationship with Montesinos and Fujimori. In two chapters, Roberto described Montesinos’s visit to Nápoles, his trafficking of cocaine with my father, the delivery of a million dollars for Fujimori’s campaign, the new president’s grateful phone calls to my father, and the offer of cooperation in exchange for the economic assistance my father provided. At the end, a sentence caught my eye: “Montesinos knows that I know it. And Fujimori knows that I know it. That’s why the two of them fell from power.” Roberto alleged that he had been present for things that my mother and I had never heard of, let alone witnessed.

I don’t know if Roberto’s book is the one my aunt suggested we write to get visas to the United States. All I know about the matter I discovered by chance in the winter of 2003, when I received a phone call from a foreign journalist to whom I’d occasionally expressed my suspicions.

“I have to tell you something that just happened to me, and it can’t wait till tomorrow!” the journalist said.

“Go on, what happened?”

“I just had dinner here in Washington with two former DEA agents who participated in the hunt for your father. I was meeting with them to talk about the possibility of having you and them come on a show about Pablo’s life and death for American television.”

“OK, but what happened?” I repeated.

“They know a lot about the subject, and I got the chance to bring up your theory about your uncle’s betrayal. And it’s true! I couldn’t believe it when they confirmed that he’d been an active collaborator in your father’s death.”

I’d been right. How else could you explain that we were the only members of Pablo Escobar’s family living in exile?

***

Copyright © 2016 Juan Pablo Escobar.

To learn more or order a copy, visit:

JUAN PABLO ESCOBAR, son of the leader of the Medellín cartel, Pablo Escobar, is an architect, lecturer, drug policy reform advocate, and writer. He was a subject of the award-winning documentary Sins of My Father and lives in Argentina.