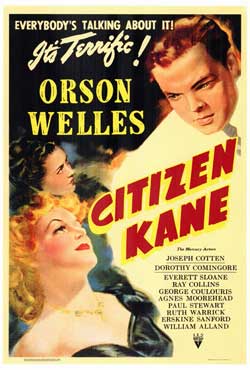

One approaches Citizen Kane slowly because of the enormous reputation that surrounds it like the vast fields, cages, and lagoons that lead up to Xanadu. Almost no one sees it for the first time without being over-prepared for it. All the plaudits, all the scholarly works, all the pop culture references—they sprawl about the film itself, always threatening to make it into the kind of museum piece Charles Foster Kane would have boxed up in Europe and shipped back to the states, never to see again. Sure, the film has lasted over seventy years, but so what? The relative youth of cinema (only about 114 years) gives us a trivial view of eternity. As Kane's director once said in another of his films, most of our art is destined to fall into the “universal ash.” Citizen Kane may yet become just another forgotten artifact.

But for now Kane still lives, and what an amazing film it turns out to be after the fifth, the tenth, the twentieth viewing. I lost count a long time ago how many times I’ve seen this movie—hell, I’ve lost count of how many times I’ve seen it projected in a theater—yet more than most other movies it continues to fascinate me. Perhaps more importantly, it continues it entertain me.

It’s a weird film. It is, simply put, unlike any other movie I’ve ever seen. Understand, I’m not saying it’s the best. I’m not saying it’s The Greatest Movie Ever Made. That phrase is like a curse attached to this film, condemning thousands, maybe millions, of viewers to the sad fate of seeing it for the first time and then asking, “What’s so great about that?”

It’s a weird film. It is, simply put, unlike any other movie I’ve ever seen. Understand, I’m not saying it’s the best. I’m not saying it’s The Greatest Movie Ever Made. That phrase is like a curse attached to this film, condemning thousands, maybe millions, of viewers to the sad fate of seeing it for the first time and then asking, “What’s so great about that?”

The problem with “The Greatest Movie Ever Made” title is that it is predicated on a completely asinine premise: that there is such a thing as an ideal movie to which all movies should aspire. Movies are not uniform. Each is a separate entity unto itself. You can compare them, and you can value some more than others. But to assign a unified hierarchy of achievement to them is worse than ridiculous—it’s sabotage. No film can be all films. No single movie can give you the distinct pleasure of an art film, a western, a science fiction film, a noir, a musical. No film contains every great movie star, nor every great moment. No film can give you all the different glories of cinematography.

Citizen Kane tries, though. In telling the life story of newspaperman Charles Foster Kane—and the mystery of his dying word “Rosebud”—the film takes us on a journey of different styles and moods. What makes it such a fascinating film is that it doesn’t really have a genre. It is unlike any other movie because the people making it were throwing in every damn thing they could think of. Cinematographer Gregg Toland fills the screen with images of exquisite beauty and mystery—shadow and light seem to dance for his camera. Bernard Herrmann’s score is low and brooding, when it’s not light and fluffy. The script by Herman J. Mankiewicz and Orson Welles is a marvel of storytelling, brilliantly utilizing multiple competing perspectives to tell a huge, sprawling story. Information is compressed and spread out, foreshadowed and repeated like motifs in a score. By the end, you have an epic. The debate over who wrote what is worthless: the thing itself is smart, funny, and moving.

At the center of the film is actor/director Orson Welles, and Citizen Kane is above all a testament to the wild energy of this invaluable artist. He is the axis around which everything else rotates. His performance as Kane is often overlooked in favor of his direction, but watch the film again and notice how many emotional notes Welles manages to hit. He’s completely charming as a young man, subtly touching in his mid-life crisis, and alternately horrible and pitiable as a ruined old recluse.

His direction is a virtuoso act. Nearly every shot in the film is interesting in and of itself. Perhaps this is why so many critics and directors insist on saddling the film with the Greatest Ever moniker. Citizen Kane simply has more going on than most movies. It is entirely possible, I suppose, to dislike the film for this very quality. This is a busy movie. Welles embraced the medium of film as a way to try new things. Or, at least new things to him. Many of his innovations had actually been done before (see Toland's work on John Ford's The Long Voyage Home for a preview of some of Kane's photographic effects), but Welles and his team seemed to have combed through every stand-out idea anyone ever had about framing a shot and applied them all to this film. No shot in the movie is a typical movie shot. No sequence is a typical movie sequence. The cumulative effect is wholly unique, even in the director's impressive body of work.

I’m reminded of a scene in Foreman's Amadeus in which a critic tells Mozart that his music has “too many notes.” Citizen Kane has the same virtue, and like Mozart’s music, it can be mistaken for overkill. Yet, maybe because of this, Kane rewards repeated viewings more than any other movie I can think of. I have always loved the film, but for years I frankly found it cold. I thought it was visually arresting, but not particularly moving. Yet, watching it again recently, I was struck by how much the film increasingly moves me when I revisit it. Surely that’s a sign of great art: the ability to deepen with closer inspection. The more you see it, the more there is to see. The more you know it, the more mysterious it becomes.

This is true because the film is constructed as a mystery without a real solution. Sure, we find out what Rosebud is, but we never really find out what Rosebud means. As Thompson, the reporter investigating Kane’s life, says at the end, “I don't think any word explains a man’s life. I guess Rosebud is just a piece in a jigsaw puzzle, a missing piece.”

That acknowledgment might be the single most revolutionary thing about Citizen Kane. It goes against Hollywood's cardinal rule: tell the audience that everything is okay. Kane does not tell you that everything is okay. It is a grand tragedy, the rise and fall of a distinctly American figure, and, most transgressive of all, it the American dream retold as a Gothic nightmare. It’s a rags-to-riches story that ends in defeat and failure. Money—and, by extension, capitalism itself—operates in the film like morphine, deadening surface pain and obscuring the real torments underneath. When Charles Foster Kane drops dead at the end of some long, lonely hallway in his hodgepodge castle estate, the door slams shut on a life that we can never really hope to understand. But, as Thompson points out, we can never really hope to understand anyone. As Welles would tell an interviewer years later, we are all made up of our contradictions. That insight is, I think, the central intellectual force of most of Welles's films.

Citizen Kane is a brilliant work of art, and like many brilliant works of art it rewards inspection and re-inspection and deeper contemplation. In it you find many of the themes—old men and disintegration, friendship and betrayal, and above all the essential mystery of character—to which Welles would return again and again in his later films. The more you watch it, the more, perhaps, you will like it and find it strangely affecting. One need not come to it on bended knee expecting a revelation. One need only come to it.

Jake Hinkson is the author of several books, including the novel The Big Ugly, the newly-released short story collection The Deepening Shade, and the essay collection The Blind Alley: Exploring Film Noir's Forgotten Corners.

Read all of Jake Hinkson's posts for Criminal Element.

PS. Check out t[url=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zyv19bg0scg]he original trailer to Kane[/url]. It’s pretty cool.

For all the many times that I have seen this film (and I have taught it, too), I have never been bored for a single instant while I was watching it. As you say, it is infinitely re-visitable, and so dense as to be virtually bottomless. The perpetual freshness of “Citizen Kane,” which has been proven over time, is just one more reason why people [u]will[/u] call it The Greatest Movie Ever Made – yes, that’s a little silly, but they are reaching for a tribute commensurate with the impact of the film. If we all simply call it ONE of the greatest movies ever made, I doubt there will be much argument.

When I was a kid, one of our local TV stations had two standbys when a Milwaukee Braves game was rained out: “King Kong” and “Citizen Kane”. As a result, I’d seen both films many a time before I wrote my age in double digits. And even though most of “Kane” went over my head at that age, there was still something about it that fascinated me enough to make up for the disappointment of missing a game.