Welles followed it by directing an ambitious adaptation of The Magnificent Ambersons, producing Journey into Fear, and attempting to make a South American documentary-drama hybri, It’s All True. All of these projects had been flops of one kind or another, and by 1945, Welles knew if he was going to survive in Hollywood, he desperately needed to establish himself as a conventional filmmaker.

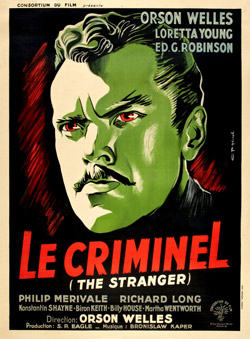

He got his shot when producer Sam Spiegel hired him to make The Stranger, a thriller about a woman living in a small college town, who discovers that the mild-mannered professor she has just married is really a notorious ex-Nazi mastermind. Welles was cast as the villain, with Loretta Young as his unsuspecting wife and Edward G. Robinson as the government investigator snapping at his heels.

The results weren’t bad, and the film made money, but none of it was enough to stop the bleeding. Welles hung around town a few more years—just managing to make The Lady from Shanghai and Macbeth—before he ran off to Europe to begin his career as an independent filmmaker in earnest.

So what are we to make of The Stranger? It holds an odd place in Welles’ filmography. He made films which were taken away and mangled (The Magnificent Ambersons, The Lady from Shanghai, Mr. Arkadin), but he made The Stranger in a conscious attempt to duplicate the conventional Hollywood thriller. In other words, here is the only example of Welles ceding artistic control to his own ideas of convention. Welles—who always flouted convention—here attempted to embrace it. What The Stranger demonstrates, however, is that the director only ever had a fuzzy notion of what exactly constituted Hollywood convention in the first place.

So what are we to make of The Stranger? It holds an odd place in Welles’ filmography. He made films which were taken away and mangled (The Magnificent Ambersons, The Lady from Shanghai, Mr. Arkadin), but he made The Stranger in a conscious attempt to duplicate the conventional Hollywood thriller. In other words, here is the only example of Welles ceding artistic control to his own ideas of convention. Welles—who always flouted convention—here attempted to embrace it. What The Stranger demonstrates, however, is that the director only ever had a fuzzy notion of what exactly constituted Hollywood convention in the first place.

The Stranger tells its story in, more or less, a straight ahead manner. Loretta Young delivers a guileless performance as the blushing bride, who discovers her husband is a monster, and Edward G. Robinson plays a variation on his role from Double Indemnity, the no nonsense fast-talking snoop. Welles puts in some thriller touches (the best of which is the hiding of a body in the woods) and builds his story up to a dramatic, over-the-top showdown in a clock tower.

Here's the theatrical trailer:

For Welles-aficionados, there are some good moments sprinkled throughout (the director was incapable of completely subsuming his personality): a speech about the dangers of dormant fascism, a nice visual throwaway of Welles in a phone booth doodling a swastika on a notepad, and a performance by Billy House as a distinctly Wellesian clown—a recurrent figure in many of the director’s films. Alas, some of his touches were nixed by the producers of the film. For instance, he had wanted to cast his favorite actress Agnes Moorehead as the investigator, only to have Spiegel insist on Robinson. There was also a protracted opening sequence cut by producers. Welles claimed it was the best thing in the movie, although the least conventional.

Taken on its own merits, The Stranger is a handsome and entertaining film, but one which is conspicuously lacking the fire-in-the-belly that marks the director’s best work. Welles gives a pretty hammy performance as Franz Kindler, the Nazi mastermind whose mild-mannered disguise is about as subtle as a silent film villain. It is in his portrayal of the villain, and in the wacky ending of the film, that you get a sense of Welles’s grasp—or lack thereof—of his material. As both a writer and a director, he was obsessed by the ambiguity of character, the ways in which a man can be both good and evil, strong and weak, admirable and contemptible. He simply wasn’t very good at delivering a “typical” thriller about a monster; it meant repressing his own sense of the dichotomy of human character. Once that sense was gone, there was no idea left for Welles to dramatize onscreen, leaving him only plot points to touch on his way to a violent climax.

Although The Stranger was, interestingly enough, his most successful film at the box office, Welles distanced himself from it as the years went by. It was the one film, he said, that he’d made “for them.” He fled Hollywood a couple of years after the movie was released, and while things were never easy for him, he did manage, more than once, to create great art on his own terms. It should be noted, though, that many people in Hollywood were able to bridge the gap between art and entertainment in a way Welles found himself unable to do.

The accepted “noir canon” is replete with great movies which were considered conventional crime thrillers at the time they were made. Some readers might see this as evidence that Welles was undisciplined and reckless, an egotistical loose cannon. I disagree. I think he simply lacked the ability to be a popular filmmaker. For evidence of this you could look at Citizen Kane or The Trial or Chimes at Midnight, great films which have, nevertheless, never appealed to wide audiences. Or you could look at The Stranger, his failed attempt to do it the conventional way.

Jake Hinkson is the author of several books, including the novel The Big Ugly, the newly-released short story collection The Deepening Shade, and the essay collection The Blind Alley: Exploring Film Noir's Forgotten Corners.

Read all of Jake Hinkson's posts for Criminal Element.

PS. Welles always treated this film like an unloved child, telling one intervewer that of his films, The Stranger “was the one…of which I am least the author.” It is still, however, pretty damn entertaining.