But if you were to take a tissue sample of my writing and centrifuge it and place it under a microscope, I suspect the DNA would match to an earlier point in the crime fiction genome. To my teens, in fact, when I read, if not all, then certainly a majority of the fifty or so Nero Wolfe detective novels authored by mystery grand-master Rex Stout.

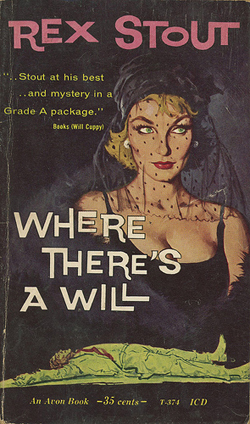

Stout—who was then still actively writing—was the first “series author” whose canon I had encountered, such that the thrill of reading one book was heightened by the knowledge that dozens more awaited. And while most of those books came from the public library, Stout’s were the first dime-store paperbacks (fifty cents at the time) that I actually purchased with my own paper-route money, placing his work on a lofty pedestal alongside Spider-Man, wax lips, and Drake’s Ring Dings.

Rex Stout wrote over 70 Nero Wolfe novels, novellas, and short stories over the course of an unusually prolific writing career that stretched from pre-World War II (Fer-de-Lance, 1934) to post-Vietnam (A Family Affair, 1975). Politically progressive, he was a founding member of the American Civil Liberties Union who famously ignored a subpoena from Joseph McCarthy’s House Un-American Activities Committee. Commercially successful (“no man but a blockhead ever wrote except for money”), Stout commanded a worldwide audience that included the Belgian surrealist René Magritte, who named several of his paintings after Nero Wolfe novels.

Between 1934 and 1966, Stout consistently published two to four Nero Wolfe novels, novellas or short stories per year—a prodigious output for most writers working full-time. Only Stout didn’t work full-time. “I work for 39 consecutive days each year,” he is quoted in his New York Times obituary. “I figure on six weeks for a book, but I shave it down.”

I can recall as a teenager seeing Stout interviewed on television. I believe the show was called Book Beat. In explaining his literary fecundity, Stout described his writing routine as follows (and I’m paraphrasing here): “I start typing on page one and I don’t stop until I get to the end. And then I’m done. I never go back and change a word.”

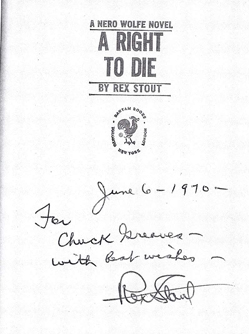

In the summer of 1970—my fifteenth year, Stout’s eighty-fourth—I had an attenuated encounter with my literary hero. It all began at a backyard barbeque at my family home in Levittown, New York, where an uncle down from Brewster noticed me reading a Nero Wolfe novel.

“You like him?” my uncle asked me.

“He’s the best,” I replied, or words to that effect.

“He’s my neighbor. Would you like his autograph?”

What writers have influenced my work? The answer, naturally, is all of them. In some cases the influence is both proximate and obvious, while in others it is so subtle as to be unconscious. But perhaps it is Rex Stout who—like his “one-seventh of a ton” alter ego—looms largest of them all.

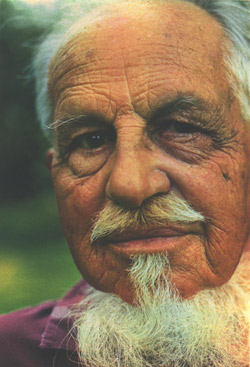

Rex Stout image via NeroWolfe.org

Chuck Greaves spent 25 years as an L.A. trial lawyer before turning his talents to fiction. Hush Money, his debut thriller, stars Jack MacTaggart, a square-jawed wiseacre who bears an uncanny resemblance to a guy named Archie. Learn more at chuckgreaves.com.

Read an excerpt of Hush Money.

Wonderful article. Thank you so much. Like you, many of us started very young but revisit the brownstone regulary. Stop by http://www.nerowolfe.org — there’s over 1200 pages about Rex Stout, Nero Wolfe, and all those tidbits that make the brownstone a special place. But I do I hope you’ve given up Ring Dings and graduated to shad roe ;-D

Carol, webmaster, http://www.nerowolfe.org

You had me at ” Auctorial.” Rex Stout not only gave us great mysteries to read, (and try to solve ) he also made my beloved New York City jump off every page. And I envy your autographed copy of A Right to Die.

Good to know I’m not the only dinosaur (S. Rex) out there. As for shad roe, I say ‘Phui.’

Ahem: that’s “pfui.”

Love!!