Murder, Incest, and Secret Lovers: A Brief History of Brontë Conspiracies

By Bella Ellis

November 10, 2020

Even if you aren’t a fan of classic English Literature, chances are that you will have heard of the Brontë family, of Charlotte, Emily, Anne, and their works of fiction and poetry. Of course, this is largely due to their extraordinary talents and remarkable novels that inspire and speak to generation after generation, but it is also in part because of the mystery surrounding this family of geniuses that shone so brightly in the unremitting dark of industrial Yorkshire. Living on the edge of a moor, in the deadly village of Haworth where the average life expectancy was only twenty-four years old, these three sisters defied both fate and expectation.

We may think we know a lot about the Brontë sisters; we have their home, many of their possessions, a wealth of correspondence, several pillowcases worth of hair and, of course, their novels. But actually, everything we do know represents only about five percent of their lives. It’s this very gap in our understanding that enabled me come up with the entirely fictional idea of the Brontë sisters as part-time amateur sleuths. However, the same spaces in knowledge have also spawned several conspiracies and murky ideas about their lives. Some are intriguing and plausible, and some are downright nuts. Here are a few that are particularly eye-catching, enraging, and fascinating.

Emily Brontë is perhaps the most adored and revered of the Brontë sisters. She is particularly mysterious, partly because we have very little of her correspondence compared to her sisters, partly because she never sought fame or publicity in the same way that Charlotte did, and partly because of her small but powerful legacy of poetry and one strange and compelling novel in Wuthering Heights. From these few certainties a universe of speculation has been born.

In recent years there has been a suggestion that Emily was on the autism spectrum, and in many ways, this seems likely. Emily was not one to conform to social niceties, she was incredibly shy or anti-social, depending on how you view it. She liked what she knew, she cared for only a few people and places, but in her imagination, she ruled over the vast fictional world of Gondal. The open moors, with its literal heights was where she felt the happiest and most free. There are many comparisons that I can draw between Emily and my autistic step-son, so it doesn’t seem impossible to me she had some autistic traits, and learned to live with both the challenges and talents its presents in a time long before the condition was recognised.

Of all the sisters, speculation on Emily’s sexuality also abounds. Soon you will see a bio-pic of Emily Brontë land on Netflix which imagines that she had a boyfriend, who was the basis for Heathcliff. This is not true. Emily wrote about love and loss, yes. And she wrote about desire and obsession, but they are spun out of her remarkable imagination. The idea that everything an author writes must be something they have personally lived is a very simplistic one, and would mean that our bestsellers lists were populated with adulterers and serial killers. Most of the time we make things up.

It was during this mid world wars period of fascination with the Brontë’s that the most disturbing rumour became attached to Emily. The rumour that she and Branwell engaged in an incestual relationship from childhood.

Rather delightfully, in the mid-1930s an actual imaginary boyfriend was invented for Emily by enthusiastic biographer Virginia Moore, who claimed to have discovered the name of Emily’s secret love when she was reading Charlotte’s tiny handwritten annotations in Emil’s notebook of poems. Above a poem about the grief of lost love she declared she had found the name Louis Parensell. Her biography The Life and Eager Death of Emily Brontë was published on the back of this history-changing find. However, soon after publication someone with a magnifying glass was able to go back to the notebook and discern that actually Charlotte had added the poem’s title “Love’s Farewell.’ Awkward. Imagine the Twitter storm if that had happened today?

It was during this mid world wars period of fascination with the Brontë’s that the most disturbing rumour became attached to Emily. The rumour that she and Branwell engaged in an incestual relationship from childhood. The evidence for this claim? That in Wuthering Heights, Cathy and Heathcliff are brought up as brother and sister, and the possibility that Heathcliff might be the illegitimate son of Cathy’s father. Well, nope, there was no forbidden love between Emily and Branwell.

For one thing, the real inspiration behind Wuthering Heights is there for you to find, if you care to look for it, which I did when I wrote my 2018 novel The Girl at the Window. Wuthering Heights was partly inspired by the true story of the Heatons, whose tumultuous life in the mid-1650s echoes the plot of Wuthering Heights. For another, this theory once again supposes that Emily could not create characters and plots from of her imagination. It diminishes her genius, and at its heart this theory is born out of a kind of salacious misogyny, that seeks to boil her brilliance away. Nonsense.

The other thing about Emily is that she is a perfect beacon for those of us who feel like outsiders, who are dispossessed, struggling to accept themselves, and who never quite fit. For this reason, there has always been speculation about whether she might have been a lesbian, or even identified as a man, hence her determination to stick to her male pen name of Ellis Bell. And personally, I think it’s great that people from all walks of life and experience can see something to relate to in Emily. For me, it is more likely that Emily simply wasn’t interested in real-world romantic entanglements with anyone, male or female. People fascinated her, but she preferred to observe them from a distance. She seems to me to have been much more interested in creating characters spun from her wonderful mind, and living heart and soul through her boundless imagination.

The rumour of incest also swirls around Charlotte and Branwell to a lesser degree, as some of the letters they wrote one another were very frank and emotional. Charlotte and Branwell were close. They built their imaginary world of Angria between them, and were constant childhood playmates. They also lived through similar experiences of forbidden love, and bitter rejection. When she studied in Brussels, Charlotte was passionately in love with her tutor Constantin Héger, though it was almost certainly unrequited. She poured out her feelings to him in a series of highly emotionally charged letters, that we only know about today because Madame Héger took the torn-up pieces of the letters out of the waste bin and sewed them back together—we will never know why. At the same time, Branwell was consummating an affair with his employer’s wife Mrs. Robinson, who he truly loved. But when the affair was discovered he was sacked, and his sister Anne, who also worked for the Robinsons, was obliged to resign. Both Charlotte and Branwell were going through devasting emotional turmoil at the same time. However, as a woman, Charlotte was obliged to lock her emotions away beneath a tightly corseted surface of serenity, while Branwell began an ultimately fatal downward spiral of self-destruction of drug and alcohol abuse. This I think is the strongest evidence that their relationship was a normal sibling one. Charlotte loved her brother, but she hated him too. Hated how he made a show of his pain, in way that she could not. And hated how he wasted his life and talent instead of channelling his pain into art, the way that she did. Attached to this is the idea that actually Branwell had been caught seducing the young son of the Robinsons, and that the affair was a cover for his true crime. This seems exceedingly unlikely for a variety of reasons, mostly that if your son had indeed been abused by his tutor there are far better ways to cover it up than with an affair with your wife. But also, because Branwell was a lifelong womanizer, and quite probably had fathered an illegitimate daughter before working for the Robinsons. There was nothing about his life the showed an unnatural interest in children, but plenty that showed his dramatic pursuit of women.

But never mind all of that!

What if Charlotte was actually a serial killer, a poisoner who bumped off her siblings and rivals over a period of months before being dispatched herself by an equally murderous husband Arthur Bell Nicholls soon after they were married? In 1999 these outrageous claims were made by author James Tully who based a novel on his belief that Arthur Bells Nichols set out to murder the entire family, after seducing Charlotte into being his accomplice. He claimed that by murdering Anne and Emily, very successful and wealthy Charlotte planned to inherit the royalties from their far less successful books. Unable to publish this theory as non-fiction, as no publisher would touch it, he turned it into a novel called The Crimes of Charlotte Brontë, and it is, in my view, utter nonsense. Anyone who could think this of Charlotte has done nothing to get to know or understand her, her life and personality. Charlotte is the most ‘visible’ of the sisters, thanks to the wealth of letters that she wrote to her friend Ellen Nussey, which Ellen kept despite promising to burn them. Charlotte was not a perfect woman but she was a human one though. She was ambitious, driven, jealous, bitter, deeply depressed at times. But she was also resilient, passionate, loyal and pragmatic. For me, what shines out of her letters more than anything is her deep love for her siblings, her endless grief at their deaths, and the image of her struggling to write on with those she has relied on as creative collaborators from the cradle. Charlotte was many things, but she was certainly not a murderer.

Of all the sisters it seems Anne is the only to escape any distaste allegations, other than the notion that she was not as talented as her sisters, which I hope is an idea that is rapidly losing traction. So, I shall happily conclude with a long-running theory that as only recently been put to bed, the idea that it was really Branwell that wrote Wuthering Heights. A recent study published by Oxford University press used ‘stylometry’ to establish once and for all who penned the famous novel. Using writing samples for both Branwell and Emily the study was able to create authorial fingerprints for each Brontë sibling and through stylistic analysis was able to prove that Branwell did not write Wuthering Heights and Emily did. That is at least one rumour that we can categorically quash.

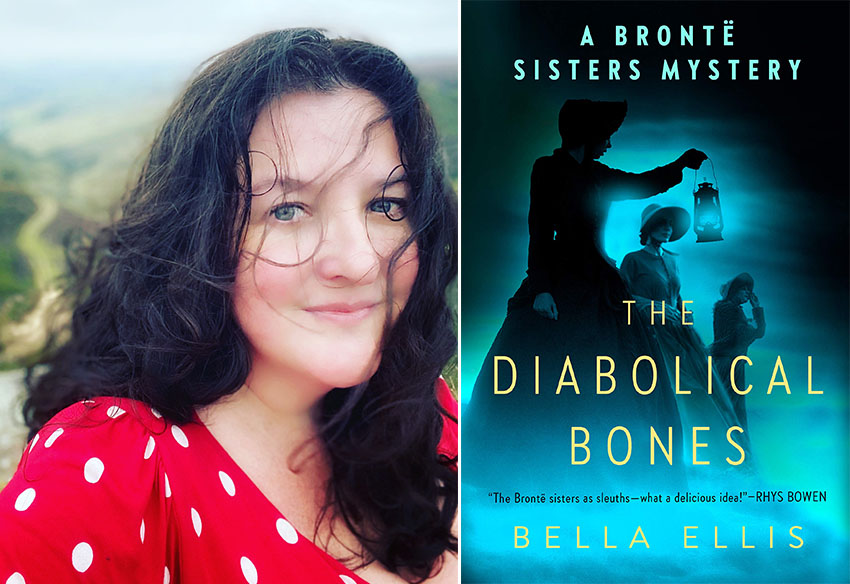

About The Diabolical Bones by Bella Ellis:

Haworth Parsonage, February 1846: The Brontë sisters— Anne, Emily, and Charlotte—are busy with their literary pursuits. As they query publishers for their poetry, each sister hopes to write a full-length novel that will thrill the reading public. They’re also hoping for a new case for their fledgling detecting enterprise, Bell Brothers and Company solicitors. On a bitterly cold February evening, their housekeeper Tabby tells them of a grim discovery at Scar Top House, an old farmhouse belonging to the Bradshaw family. A set of bones has been found bricked up in a chimney breast inside the ancient home.

Tabby says it’s bad doings, and dark omens for all of them. The rattled housekeeper gives them a warning, telling the sisters of a chilling rumour attached to the family. The villagers believe that, on the verge of bankruptcy, Clifton Bradshaw sold his soul to the devil in return for great riches. Does this have anything to do with the bones found in the Bradshaw house? The sisters are intrigued by the story and feel compelled to investigate. But Anne, Emily, and Charlotte soon learn that true evil has set a murderous trap and they’ve been lured right into it…

Comments are closed.

So interesting! Thank you.