For many readers of mysteries, this ranks is one of their favorite novels ever. It’s been re-released in the US, but the film made of it decades ago is not (yet) available on Netflix. I would love to see the film version, but the novel is so vivid, I don’t actually need actors. Pages and pages go by while Canon Avril, shuffling about his rooms, wakes up to the reality of what he knows. Jack Havoc, dangerous killer, is just across the yard in the church. Of course. That’s where he is. For pages and pages Avril watches the fog lift, begins to understand how the back entrance to the church has gone unused and unremarked. Now Avril is not a stupid man. He considers that the smart thing to do, the only thing to do, is to call the police and report that he has found the man they are all hunting, the man who is responsible for four brutal killings. Even when Avril lifts the phone, we know where he is headed. He gets a little help from Allingham in that the phone has been disconnected and that solidifies in his mind what he was going to do anyway. Yes, he goes to the church.

Another writer perhaps might have tried: he trips, he falls, Havoc finds him and slices his throat. Or a gun materializes and goes off (even though Jack Havoc is known for the knife). And there is always the option of knocking the old clergyman over the head with a statuette. But no, Allingham decides on talk. Dialogue. This scene and the final one are what I remember most about the novel.

When people talk—bad guy and good guy—and when the talk isn’t at all simple, wow is all I can say. This is tension. This kind of extended dialogue makes me shake as I read it. Yes, it’s morality making its way into fiction, but nothing simple, only as simple as say, the Bible, which is not simple at all. Jack Havoc has a birth name—Johnny Cash. Canon Avril says, “‘Johnny Cash’ . . . in exactly the same voice which he had used so many years before, ‘come out.’”

There is the play of a flashlight beam on the clergyman’s face. “You’re alone.” Havoc is astonished, amused. Definitely the game is in his favor.

“Of course I am.”

Ah. “You’ve telephoned, though.”

What does the Canon do? He could lie. He could say, “Yes, they’ll be here any minute. Might as well let me live.” He says, instead, “No one knows that you and I are here.”

And so they talk. Oh, I’m hooked on scenes like this in which the person to whom we hate to see harm done and the one who intends harm press and withdraw . . . words. Nobody runs away, nobody shouts, “I’ll kill you, you bastard.” They inch toward each other first. The conflict is still there. The evil doesn’t go away. But there is building a oneness in victim and victimizer.

I won’t tell the ending. If you haven’t read it, you simply must.

Our wonderful Laura Lippman works a variation on this kind of conversation. She has a person who has already done wrong inveigle himself back into the life of the person he wronged in I’d Know You Anywhere. Their conversations are the meat of the book.

Hitchcock loved to do these conversations, and he did them in a number of films. I hold my breath when those fantastic strangers speak on the train or when Charlie, once she suspects her uncle Charlie, talks to him in Shadow of a Doubt.

For many of us, it’s the word not the sword that terrifies.

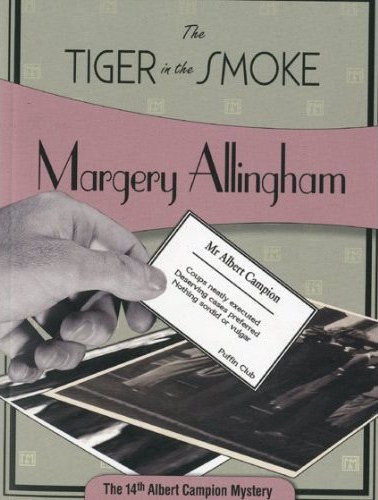

Image courtesy of felon_bottletop

Kathleen George is the author of The Odds, which was nominated last year for the Edgar® for best novel. Read an excerpt from her latest novel The Hideout here.

Kathleen.

Marjorie A. is my favorite writer. I am leading a group on Sweet Danger for our Mystery Then and Now Book Club on Nov 3rd @ Mystery Loves Company as we compare it and Val McDermid’s Place of Execution. Sometimes I love her work so much I can’t even put into words why. But everytime I pick up one of her books I am amazed by her humor and wit, black and otherwise; humanity, and sheer love of a turn of a phrase and a plot line. When she (and Campion) is on her game, everthing just clicks. What are your thoughts on Sweet Danger?