Sometimes the characters and settings of a novel are so perfect that the author pretty much can’t go wrong with the story. Tell me that you’ve got a 1940 work of noir fiction set around a North Carolina roadhouse and that features characters with names like Smut Milligan, Catfish Wall, and Badeye Honeycutt. Add that moonshining, card and dice games, love triangles, bare knuckles brawling, and such figure in regularly. Mention that the book was written by an enigmatic guy who only authored the one novel and that it has been praised by the likes of Flannery O’Connor, Raymond Chandler, and George V. Higgins. And okay, okay, go ahead and ring me up, cause you had me sold just with the roadhouse, Smut, Catfish, and Badeye.

Sometimes the characters and settings of a novel are so perfect that the author pretty much can’t go wrong with the story. Tell me that you’ve got a 1940 work of noir fiction set around a North Carolina roadhouse and that features characters with names like Smut Milligan, Catfish Wall, and Badeye Honeycutt. Add that moonshining, card and dice games, love triangles, bare knuckles brawling, and such figure in regularly. Mention that the book was written by an enigmatic guy who only authored the one novel and that it has been praised by the likes of Flannery O’Connor, Raymond Chandler, and George V. Higgins. And okay, okay, go ahead and ring me up, cause you had me sold just with the roadhouse, Smut, Catfish, and Badeye.

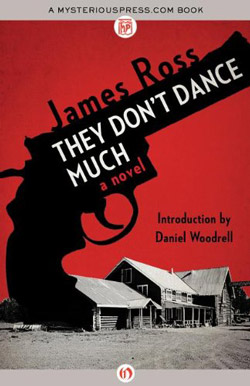

The book we’re talking about is They Don’t Dance Much by James Ross, and it just about defines “lost classic of noir” (although it’s about to be found again, via a new reprint with an intro by Daniel Woodrell).

The downbeat and gritty story is set in the area of Corinth, North Carolina, (not terribly far from Durham) and told in a fittingly deadpan tone, by a guy named Jack McDonald. Jack is a down-on-his-luck farmer whose crops have failed him to the point where he can’t keep up payments on his land (he can’t even pony up what he owes for his mother’s funeral from three years back). Jack has to give in and sell his farm and all its trimmings, just to keep the bill collectors off his back. But he’s spared the indignity of going on relief when he’s offered gainful employment by Smut Milligan. Before we get into the nature of that work, here’s a little background on Smut, by way of Jack:

Smut Milligan was a couple of years older than I was, but I knew him pretty well. His first name was Richard, but everybody called him Smut. I don’t know what his last name really was. He didn’t know either. He was adopted by Ches Milligan and his wife when he was a baby. Ches Milligan used to run a grocery store in Corinth. His wife ran him. When she had his spirit broken—from what they tell me—she took a notion to go to an orphanage in Raleigh and get a baby there. She wanted a boy baby. She liked to tell males where to head in.

Smut was three or four years old then, but from what I’ve heard he never paid much attention to Mrs. Milligan. He was a tough kid in school and played hooky a lot. In the fall he’d traipse off to hunt muscadines and in the spring he went fishing in Pee Dee River, and sometimes in Rocky River. He gave the Milligans a lot of trouble. The old lady probably wished she’d let him stay in the orphanage. But she died when he was about sixteen. From then on Smut didn’t have any argument about what he did.

At the story’s opening, Smut runs a filling station. It’s a place where getting your gas tank loaded and oil checked are only a part of the attraction. You can also buy liquor that is home-brewed by Catfish Wall, who is like an alchemist with his inspired spirit potions. You can buy a hamburger lunch and grab a pack of Camels, go in the back room and try your luck at a game of poker or blackjack (your luck is likely to be thin, since Smut deals with a stacked deck), and, hell, if you want to you can just prop yourself up on a nail keg and sip a bottle of Coca-Cola while tolerating the sweltering Carolina heat.

Here’s Jack, describing a typical day around the place:

It was the usual Monday. Sold a little gas. Wiped a lot of windshields and filled up radiators with water. I listened to the radio awhile, but it wasn’t long before the only programs I could get were inspirational programs that told you how to get more out of life. I shut it off and went outside to my nail keg.

The store’s bringing in a plenty good take for Smut. But he’s not satisfied. Smut is a restless soul with plenty of ambition and a trouble-making bent. He decides to expand his filling station/store and make it a roadhouse. He figures the roadhouse will be wildly successful, and it seems he may want to open it as a means of attracting the presence of Lola Fisher.

Lola is a stacked beauty with whom Smut has been playing around since the two were teenagers. But Lola and her mother have high society ambitions, so there’s no way they were going to have Lola wedded to a common cuss like Smut. Instead, she marries Charles Fisher, gentrified son of a successful hosiery mill owner. So Lola’s got herself all squared away in the social stratification and material comforts departments. But that doesn’t mean she doesn’t still get off on turning the heads of men other than her hubby, and she especially likes revving up Smut’s engine. The roadhouse will give Smut and Lola a base for their flirtatious interactions, and then some.

So Smut makes his plans to start the roadhouse, and he offers Jack a job there, as a cashier and general “whatever needs doing” worker. Here’s how Smut describes his vision of the roadhouse to Lola:

The River Bend Roadhouse. Dine and dance. Drink liquor and make love. Slot machines and high dice. Name your sin and your favorite utensils. We’ll have it.

Things start well enough at Smut’s roadhouse. He hires a staff of five or six, Jack among them, who will do everything from cook to wait on the guests both curbside and at the indoor tables. He advertises in newspapers and on roadside billboards. Customers are plentiful. They get the local millworkers and schoolteachers, visitors in town to see their school play Duke in football, lovers on hot dates, and hangers-about, et al. People come in for a steak sandwich or a spin on the dance floor, a hit off Catfish’s booze or a game of cards, a turn at the pinball and slot machines or to pump nickels into the nickelodeon and have it play a tune that suits them at the moment . . . but they come, and they spend money.

Smut Milligan is the kind of unsettled soul who doesn’t know how to leave well enough alone, however. Smut gets into a dice game with some locals and, him being out of luck that night and the dice not being fixed in his favor, he loses big. The debt he runs up from that loss is so immense that he’s going to be up against it to make his next payment on the roadhouse lease. And he’s got pressure on him because there’s a greedy and fiscally savvy man hanging around, whom Smut knows is just dying to move in and take over the roadhouse if Smut can’t keep it afloat. All of these factors drive Smut to commit a desperate act, one in which he implicates Jack; this act, and all that happens in its aftermath, is the central focus of the story.

The funny character names notwithstanding, They Don’t Dance Much is a grimly serious tale. This is not Snuffy Smith, the Novel. A better comparison would be another Southern tale set around a public establishment, which happens to be one of my personal favorite works of fiction: Carson McCullers’s The Ballad of the Sad Café. Ross’s lone novel is both excellent roadhouse noir and just plain good Southern literary fiction. Call it Flannery O’Connor meets James M. Cain.

And can I just say that one character’s misuse of a phrase makes the whole book for me? Catfish tells Jack, while the two of them discuss a mutual acquaintance who’s known to go on drunken benders, that this man sometimes suffers from “delicious trembles.” Delicious trembles. If that’s what DTs actually stood for, I would want some. Why isn’t there a band named The Delicious Trembles? Anybody wanna start one? Sigh. Delicious trembles.

We’ll close with another sample of the text. Here, Jack is reflecting on the roadhouse’s nickelodeon, and how people love coming in and having it play songs for them. He talks about the different tunes the various customers favor, and gets to musing about one that satisfies the jones of one of their regulars:

Baxter Yonce had a favorite record too. It was about the strangest of them all: ‘Nearer My God to Thee.’ Baxter didn’t go to church much, and he drank plenty of liquor; I couldn’t see why he was so crazy about a hymn. We had a hard time finding it in the music stores, but he raised so much hell about it that Smut finally ordered it from Chicago to pacify him.

Baxter would come in late at night, about three sheets to the wind, and sit in a booth over on the dance-hall side. He’d watch his chance and slip his record on the nickelodeon. Then he’d beat it back to his booth and go back to drinking his beer, or whatever it was he was drinking that night. In a minute the nickelodeon would commence rolling out ‘Nearer My God to Thee.’

Sometimes some of the customers would look like they thought it was out of place for a hymn like that to be played on a nickelodeon in a roadhouse. That never worried Baxter Yonce. He would sit there with his eyes shut, swaying his big head from side to side and humming the song to himself.

One night I had told Smut about it. I told him that some of the customers looked a little strange when that hymn began playing. But Smut was making good money then and he was pretty independent about it. He said if the customers didn’t like ‘Nearer My God to Thee’ they could go to hell.

Brian Greene writes short stories, personal essays, and various things about books, music, and film. His articles on crime fiction books and authors have also been published by Noir Originals, Crime Time, Crimeculture, Paperback Parade, Black Mask, and Mulholland Books. He lives in Durham, North Carolina, with his wife Abby, their daughters Violet and Melody, their cat Rita Lee, and too many books and CDs.

great article! extremely well written. and i’m officially changing my name to smut milligan.

It was a delight to read your excellent review of “They Don’t Dance Much.” I live in Durham as well, as I have just published a long biographical article about James Ross in the 2013 North Carolina Literary Review. I also wrote a piece on the book for Oxford American: http://www.oxfordamerican.org/articles/2012/sep/11/essay-james-ross/

I’m glad to hear you enjoyed this. And good to know there’s someone else kicking around Durham who knows and appreciates this novel. I just read your Oxford American piece – very nicely written, and fills in some holes about Ross. Thanks.

Nice review; thanks for writing about this book, which is currently delighting me. While there is an unincorporated community called Corinth in Chatham County NC (near Durham, as you say), the novel is apparently set in a fictional Corinth that is in or close to Ross’s native Stanly County (outside of Charlotte, NC), which has its southern and eastern borders defined by the Rocky and Pee Dee rivers mentioned in the book. Another clue that the novel is set in this area is that the character Wilbur Branson owns several slum rental houses in Charlotte; collecting rents and maintaining these from Chatham County would be a royal pain in the 1930s. The novel also mentions the hosiery mill workers a good bit; there was a heavy concentration of textile mills in the small towns between Charlotte and Greensboro / High Point; while there was some textile industry in the Durham area, tobacco processing was the major industry in Durham.