“Once upon a time there lived in Berlin, Germany, a man called Albinus. He was rich, respectable, happy; one day he abandoned his wife for the sake of a youthful mistress; he loved; was not loved; and his life ended in disaster.”

“Once upon a time there lived in Berlin, Germany, a man called Albinus. He was rich, respectable, happy; one day he abandoned his wife for the sake of a youthful mistress; he loved; was not loved; and his life ended in disaster.”

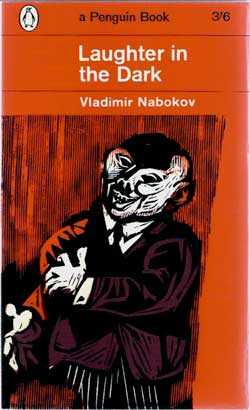

That succinct paragraph opens Laughter in the Dark before Vladimir Nabokov dutifully unfolds the spiraling downward fall of middle-aged art critic Albert Albinus and his gripping obsession with the 16-year-old Margot Peters. The novel was first published in Russian in 1932 under the far more captivating title Camera Obscura, and twenty-three years later Nabokov would tackle a similar theme of an older man with a young girl in the groundbreaking Lolita. But, whereas the famed nymphet of the 1950s gains a certain amount of pity for her situation, Margot comes across for what she is: a spoiled, conniving, and ultimately quite cruel femme fatale.

An adulterous affair requires no other impetus than old fashion lust but Nabokov provides Albinus with two main ‘reasons’ for his travelling eye. His wife, Elisabeth, can be a bit dull between the sheets, or, in his own words, “she failed to give him the thrill for which he had grown weary with longing.” He also finds her rather boring in conversation and doesn’t particularly appreciate her input when company is present. He admits he married the docile Elisabeth “because it just happened so.” Albinus spots the young Margot who, unbeknownst to him, has survived financially as a nude model, been ‘taken care’ of by an older woman who discreetly pimped her ‘innocence’, and finally turned to a life of prostitution for room and board. Still desperate and wondering if she would have to sell her furniture, she takes an ordinary job at a local movie theater that is routinely attended by Albinus.

Margot’s trained eye recognizes an easy mark and lets the wealthy suitor set her up in her own apartment with additional funds for furnishing and then maliciously sends a letter to his house with the hopes that Elisabeth will put an end to his coming around. Nice gal, huh? Elisabeth finds the letter as planned and instead separates from Albinus. Surprisingly Albinus, though distressed, doesn’t seem as upset with Margot’s supercilious actions, and, in fact, they have endeared him more to the young conniver who he quickly forgives. It’s hard to fathom at times how Albinus can be so completely devoted to such a spoiler of a human being especially when Irma, his young daughter, turns sick and dies. Margot glibly tells him, “don’t be so depressed, woggy.” Her rationale is that Elisabeth and the rest of the family had turned the little girl against him anyway and adds, “if I could have a child, I’d rather have a boy.” Since Nabokov presents Albinus as a caring father it’s easy to imagine that he would at this point kick Margot to the proverbial curb, but no, he quickly moves on. Even the hall-porter observing the seemingly happy Albinus declares to the postman, “It’s hardly believable … that Herr’s little daughter died a couple of weeks ago.”

Margot has a change of heart concerning her suitor, realizing his wealth and position as a theater critic can secure her acting parts and, after a time, the talentless Margot is featured on the silver screen. But she cringes when she sees how gawky and stiff her acting is, feeling “like a soul in Hell to whom the demons are displaying the unsuspected lining of its earthly transgressions.” To take her mind off her unsuccessful debut, Albinus whisks Margot away for an extended holiday. Along for the adventure is their chauffeur named Rex, a former flame of Margot’s (a fact hidden from Albinus), and the lovebirds seize the opportunity to reignite their romance. Albinus catches wind of it and while he’s driving Margot away from the hotel and Rex, he crashes the car in a horrific accident that leaves him blind.

Margot continues her affair with Rex who parades about the house naked, mocking the blind Albinus while openly carrying on with Margot in his presence. At first, Albinus is unaware but gradually his other senses grow stronger and he is mindful he’s being played for a fool. When Elisabeth’s brother Paul comes to her with his suspicion that Albinus is being bled dry financially by the amoral couple, she asks him to go check on her ex. There, Paul discovers Rex seated nude across from the blind man, torturing him with a blade of grass that Albinus swats at as if it’s a fly. The shamed man acts “like Adam after The Fall … cowering by the white wall and grinning wanly, covered his nakedness with his hand.” Paul takes Albinus back to Elisabeth who has continuing love and sympathy for him.

Biographer Brian Boyd notes, in his indispensable Vladimir Nabokov: The Russian Years, “… now these two unglamorous characters seem the only appealing people in the whole book. Nabokov often sides with those spurned by the flashier figures at the center of his novels.” To his final detriment Albinus learns Margot is clearing out her apartment, so he goes there with a pistol intent on killing her. When he arrives, he blocks the only exit and feels a presence coming toward him. “Albinus could control himself no longer; with a fierce groan he pressed the trigger.”

Previously I’ve asserted that two other Nabokovian literary oeuvres—Despair and The Eye—could have fit quite comfortably into what we regard as the noir framework. Wikipedia describes noir, in part, as “particularly those that emphasize cynical attitudes and sexual motivations.” Add in handfuls of deceit, betrayal, victim of circumstance, and murder, and I would declare that Laughter in the Dark is one very fine piece of noir.

Edward A. Grainger aka David Cranmer is the editor/publisher of the BEAT to a PULP webzine and books and the recent anthology collection, The Lizard’s Ardent Uniform and Other Stories.

Read all of Edward A. Grainger's posts at Criminal Element.

I had the pleasure of reading this, years ago now, while I was in Berlin for a week. Picked it up there in a bookstore with English language books. It was fun to read it there, I have to say. It’s gotta be one of his darkest novels, no? The language with Nabokov of course is so great, but when you describe it as you do here, the actual bare boned plot mechanics, the sexual cruelty, it comes across completely as noir.

Scott, A very dark novel and, perhaps, another word to use is cynical. I found I lost all sympathy for the protagonist when he was able to forget the death of his daughter so easily. And, yes, the layering is obviously what elevates it to literary status.

Another ace write-up, David. I’m enjoying this series of pieces by you on Nabokov’s lesser-known titles.

I may be running out, Brian. Only so many hidden masterpieces I can bend the noir way.