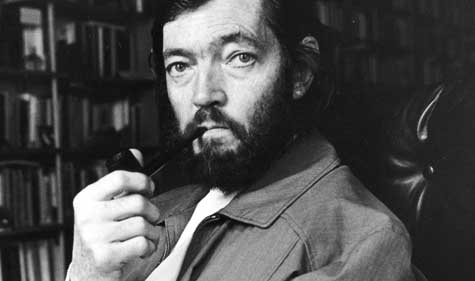

At the tender age of nine, and against his mother’s better judgement, Julio Cortázar (1914-1984) managed to get his hands on an Edgar Allan Poe collection. Years later, Cortázar recalled in an interview for The Paris Review: “[S]he thought I was too young and she was right. The book scared me and I was ill for three months, because I believed in it … dur comme fer as the French say.” But thanks to his mom spurring him to other reading (Jules Verne was an early favorite) and his robust imagination, he developed a knack for storytelling that jettisoned the distance between the real and the imaginary—eventually becoming one of Argentina’s premier novelists and short story writers. Here are a few examples from his body of work epitomizing why his surreal art still maintains such clout in the literary community.

“Blow-Up” (short story, 1959)

Cortázar’s most famous short story is about a deranged photographer, Roberto Michel, who has taken a picture of a crime in progress … or has he? What he first witnesses as a mother with her son at the park morphs—in his unhinged mind—into a woman seducing a boy for her own gratification, or, possibly, for the sexual pleasures of a man sitting nearby in a car. Later, he blows up the photo to wall size and Michel imagines the photographed people moving about, assuming new positions, as he scrutinizes the frame.

All at once the order was inverted, they were alive, moving, they were deciding and had decided, they were going to their future; and I on this side, prisoner of another time, in a room on the fifth floor, to not know who they were, that woman, that man, and that boy, to be only the lens of my camera, something fixed, rigid, incapable of intervention.

“Blow-Up” was filmed in 1966 by director Michelangelo Antonioni, veering from Cortázar’s story but faithfully adhering to the theme of visuals not always being what they initially seem and how diverse meanings can be extrapolated from a single image.

“House Taken Over” (short story, 1946)

A brother and sister, both middle-aged, live in a house that goes back several generations in their family. They have suffered setbacks in their personal lives and now cling together, having settled into comfortable routines, save the unusual sounds they begin to hear that they assume are spirits inhabiting various rooms of the home. Instead of moving out or calling a paranormalist, they simply close doors, partitioning off the rooms and allowing the otherworldly presences to occupy whatever section they desire. As the ghosts spread throughout, the siblings’ domain decreases.

We didn’t wait to look at one another. I took Irene’s arm and forced her to run with me to the wrought-iron door, not waiting to look back. You could hear the noises, still muffled but louder, just behind us.

A ghost tale (which Cortázar wrote immediately after waking from a nightmare) offers one of the best examples of how he gradually eases the natural world into the fantastical. The opening half of “House Taken Over” goes out of its way to set up the domestic serenity—brother spends his time reading and sister knits. Ho-hum. There’s no warning when reality bends in Cortázar’s hands and the ghosts begin running amok. And his storytelling (like in “Blow-Up”) deftly sidesteps tying up loose ends. Are the others former family members? Friendly? Hostile? What are their intentions? It’s left to you, the bibliophile, to discern meaning.

“Continuity of Parks” (short story, 1956, End of the Game collection)

A reader desperately wants to savor his novel—every bookworm knows that feeling, right? So he settles into his comfy green upholstered armchair and gets thoroughly immersed in the story of an anxious woman meeting with her lover. Through his reading, he disengages himself completely from the world.

Word by word, licked up by the sordid dilemma of the hero and heroine, letting himself be absorbed to the point where the images settled down and took on color and movement, he was witness to the final encounter in the mountain cabin.

The twosome who “felt it had all been decided from eternity” carefully plan their future, and it seems they have one witness to eliminate. The couple separate, and the man carrying a knife enters a house, and stealthily walks up behind the green chair where our reader is lost in his book. Now, in less capable hands, that plot could be as gimmicky as hell, but in Cortázar’s solid construction, we find ourselves metaphysically transported to that armchair as the killer approaches—and looking over our shoulders as we read.

In a 1974 Diacritics interview, Cortázar shed some light on his writing process, “… Stories drop on me like Lovecraft’s ‘color,’ they are something that comes down (or rises, of course) upon me, and there is nothing to do, except to write them, often not knowing how they are going to end.”

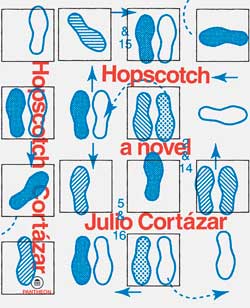

Hopscotch (Novel, 1963)

Hopscotch (Novel, 1963)

Aside from the short form and political essays, Cortázar’s most known for 1963’s groundbreaking Hopscotch. Not a mystery or crime novel per se, but, again, like “Blow-Up,” you will feel like a detective navigating its unusual arrangement. The book—often referred to as a counter-novel—can be read according to two separate arrangements of chapters: in a linear fashion or hopscotching around to parts where the earlier narrative is enhanced. The plot concerns a group of Bohemians who call themselves The Serpent Club as they party, play jazz records, and pontificate on all sorts of intellectual topics. That is, until a series of events tear them apart. Truly a stream-of-consciousness experience that New Republic praised as, “The most powerful encyclopedia of emotions and visions to emerge from the postwar generation of international writers.”

High praise and well deserved. Surreal, stylistic, genius, artistic, and daring all sum up Julio Cortázar. And there’s little doubt it originates from an upbringing devouring the pages of Verne and Poe and other magical realms. In Plural magazine, Cortázar said, “I spent my childhood in a haze full of goblins and elves, with a sense of space and time that was different from everybody else's.”

Wanna shake up your reading habits and find yourself in another world? Give Cortázar a try.

Edward A. Grainger aka David Cranmer is the editor/publisher of theBEAT to a PULP webzine and books and the recent Western novella, Hell Town Shootout.

Read all of Edward A. Grainger's posts for Criminal Element.

I didn’t much care for “Blowup” the movie and wasn’t “Hopscotch” made into a movie? I don’t care for the surrealism put in by writers. It’s difficult enough to keep up with the real stuff going on.

Then this would not be for you, Oscar. For me, after a lifetime of straightforward linear storytelling, I can use some surrealism in my diet. I come away from a J.C. read dissecting what I have read or marveling at the cleverness of the plot construction.