How To End The World In Five Easy Steps

By Andrew Hunter Murray

January 31, 2020

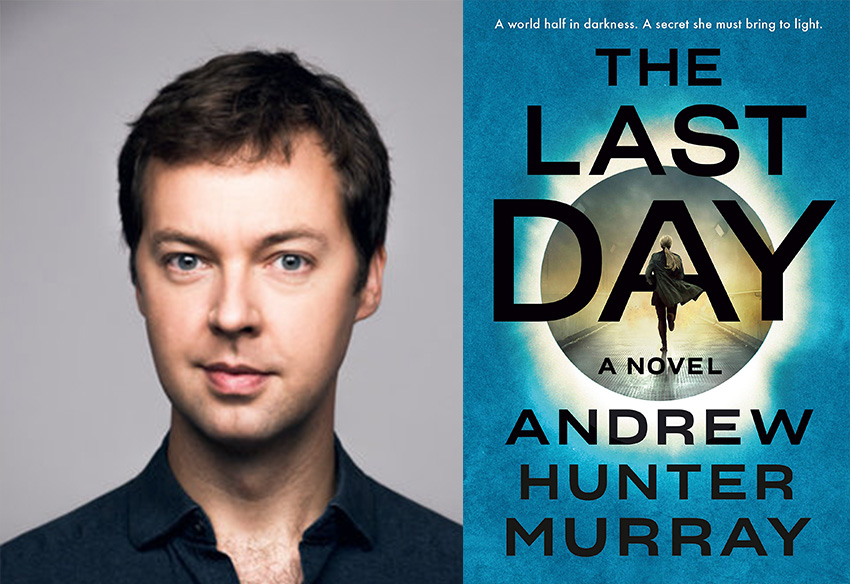

The book I’ve written (my debut novel) is called The Last Day. It is set in our world, forty years into the future—a world in which, thanks to a catastrophe in the heavens, the planet’s rotation has ground to a halt. Half the planet faces inwards, towards the sun; half faces out, towards the bleak, frozen universe. And the few governments still functioning on the sunlit side (including a British/American combo) are willing to do anything to survive.

It’s fair to say that this is an unlikely premise. I would stake a lot on it never happening. But it’s also a way of describing a world which is suffering with new extremes in climate; a world in which people have fled their homes in order to seek sanctuary; a world where the old certainties and stabilities are starting to break down, and nobody knows exactly what our home will look like at the end of this century. I grew up reading great books about worlds like this, slightly altered worlds that would make a huge change but then took that change seriously. If you’ve ever read The Day of The Triffids, where strange new plants suddenly gain the advantage over humankind, or The Children of Men, where no babies have been born for eighteen years, or The Power, where women develop the power to electrocute and the social structures of the last 10,000 years turn upside down, you’ll know what I mean.

So this is a guide to some of the principles I learned (slowly and painstakingly) during the writing of The Last Day. You’ve got your own new world you want to summon into being—or destroy. How do you get there from here?

- Find some giants with welcoming shoulders. The idea of lassoing the earth to a halt is obviously huge, impractical, and almost completely impossible. But if you befriend a scientist or two, you might be surprised at the options available to you. I got very lucky after several months of thinking about the idea and scribbling notes—I happened to remember a friend of mine who was studying astrophysics at Oxford. She got in touch with her colleagues and between them they cooked up half a dozen different ways the planet might lose its rotation. With her advice, and those of various oceanographers and other experts, I was able to make an impossible world seem much more plausible.

- Stitch in as much reality as you can… In my book, the first tremors of the earth slowing down are detected when GPS networks fall apart—and then the terrible truth is discovered by a mysterious underground lab in Germany’s Black Forest, home to a device called the Ring Laser Gyroscope. The exciting thing is that the Ring Laser Gyroscope is real, and its job is to measure the rotation of the whole planet. Another real-world entity I learned about is the network of seed banks across the planet, which exist to restock agriculture in the event of climate chaos, and which I wrote into an early draft. The mysterious team of people who run the GPS network? They’re real too. Everywhere you look, there are extraordinary things that you can sew into the fabric of your book to make the lining shimmer. I didn’t know about any of them before I started writing—but they were waiting for me nonetheless.

- …But don’t be afraid to make a leap or two. At some point, you will have to cut the strings of reality. When he was writing The Golden Compass, Philip Pullman didn’t let the fact that polar bears don’t have opposable thumbs stop him from creating Iorek Byrnison, one of the greatest armored polar bears in literary history. The kind of genetic changes in The Power would doubtless take countless millennia to unfold. And I confess that the earth’s rotation slowing to a halt in a little over a decade would require some seriously precise shenanigans in the heavens. The way you can get your audience to suspend their disbelief is by taking lots of the world you’re building seriously—and then they’ll step into the sky with you, if you ask them nicely.

- Tell a few people who you think might help (if you dare). I’m very lucky to work at a firm, QI, where our whole job is to research interesting facts. One colleague who knew what I was working on sent me a New Scientist article about ‘Hot Jupiters’, planets which orbit their stars with the same side facing inwards all the time. Proof it can happen! Others recommended various other works—about climate migration, or other new discoveries—which all added to the overall effect. This can provide a lot of good cheer at a time when Chapter 5 just won’t pull together (for example).

- Help comes from unlikely sources. The Last Day features a lot of geopolitics. But it might not have done. It might have been a completely different novel if I hadn’t chanced upon a brilliant book called Prisoners of Geography a year or two earlier. Prisoners explains the way the world’s politics has fallen thanks to its geographic features. The North European Plain which is so important to Russia, the Straits of Malacca which China is obsessed with keeping open for its own survival, Britain’s tall cliffs and deep waters which allowed it to build big ships and so dominate the world’s oceans for centuries…all of those principles ended up being mirrored in The Last Day, in a world where how you live depends completely on where you were when the earth stopped. I had no idea I’d been reading Prisoners for research. But as soon as the idea for my book came into my head I knew it would be relevant. Some of the greatest inspirations are only visible from the corner of your eye—or even in the rear-view mirror.

Those are the few tips I’ve picked up writing my first novel—and I’m sure I’ll have changed them all by the time I finish my second. Good luck bringing your own worlds to a screeching halt.

About The Last Day by Andrew Hunter Murray:

A world half in darkness. A secret she must bring to light.

It is 2059, and the world has crashed. Forty years ago, a solar catastrophe began to slow the planet’s rotation to a stop. Now, one half of the globe is permanently sunlit, the other half trapped in an endless night. The United States has colonized the southern half of Great Britain – lucky enough to find itself in the narrow habitable region left between frozen darkness and scorching sunlight – where both nations have managed to survive the ensuing chaos by isolating themselves from the rest of the world.

Ellen Hopper is a scientist living on a frostbitten rig in the cold Atlantic. She wants nothing more to do with her country after its slide into casual violence and brutal authoritarianism. Yet when two government officials arrive demanding she return to London to see her dying college mentor, she accepts – and begins to unravel a secret that threatens not only the nation’s fragile balance, but the future of the whole human race.