Grappling with a Narcissistic Character

By Emily Arsenault

March 16, 2020

I’m a podcast junkie. But about five years ago I found my taste shift from true crime podcasts like Someone Knows Something and Serial to psychology and psychotherapy podcasts like Mental Illness Happy Hour and Psychology in Seattle. I’m not sure why this happened; I might have simply grown uneasy about hearing the details of so many murders. Conversely, I was also, admittedly, writing a book about a murdered therapist at the time. But long after that project was finished, my psychology podcast habit persists.

In any case, I noticed a pattern in these podcasts. Many of their guests, or people who would write questions to the hosts—that is, often people currently in therapy or seeking therapy—would mention that they have or had a narcissistic parent.

This was eye-opening to me. I’d never much considered this topic very deeply before, or thought of it as a very prevalent issue. Thankfully, I believe I have remarkably un-narcissistic parents. I listened with more concern that perhaps I could be a narcissistic parent. Writing books is probably a sign of at least mild narcissism, after all. Perhaps I was a covert narcissist (yes, that’s a thing). Perhaps my daughter was going to be calling up therapy podcasts a couple of decades from now. I listened for what-not-to-do details: don’t make your kid do things just so you can brag about them, don’t guilt your kid about your personal disappointments, don’t wield affection as a source of punishment and reward.

According to the DSM-5, a person with Narcissistic Personality Disorder will display five or more of the following:

- A grandiose sense of self-importance

- Preoccupation with fantasies of unlimited success, power, brilliance, beauty, or ideal love

- A belief that they are “special” and unique and can only be understood by or associate with other special people or institutions

- An intense need for excessive admiration

- A sense of entitlement (to special treatment)

- Envy of others, or a belief that others are envious of them.

- Exploitation of others

- Lack of empathy

- Envy of others or the belief that one is the object of envy

- Arrogant, haughty behavior

Narcissism, like so many psychological traits or afflictions, is of course on a spectrum. Lots of people have narcissistic qualities without falling into the parameters of the personality disorder. I’ll go out on a limb here and guess that even excellent parents can probably have occasional lapses into narcissism.

Still, I was curious about the people who fall into the clinical extremes of narcissism. How they exist in the world, and how people close to them manage. With this in mind, I started to experiment with a suspense story about a teenage girl whose father, an owner of an amusement park and a doughnut empire, was absurdly narcissistic, and who involved her in all of his ridiculous business ideas.

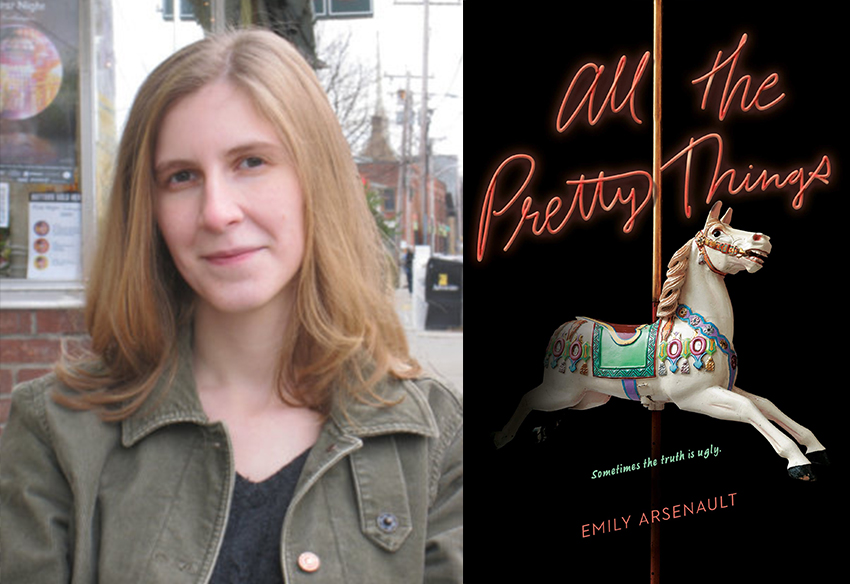

I mentioned my project to a relatively new friend, a former social worker, who surprised me by telling she would really like to read it—because, she said, her father was a narcissistic New York businessman, whom she dutifully worked for many years of her young adult life—until his business imploded. They no longer spoke to each other, had not seen each other in many years. She became one of my first readers of All the Pretty Things.

In the meantime, I started reading books about narcissism—pop psychology books and self-help books for people with narcissists in their lives. Most of these books I stopped reading about halfway through. Not because they weren’t engaging, but because I found the topic to be surprisingly uncomplicated. How a child grows into narcissism is complicated, as is dealing with a narcissist in your life. But the presentation of someone with narcissistic personality disorder is generally not complicated: essentially, such a person acts like a toddler.

For me, a big part of mystery writing is subtlety. Not just subtlety of clues for the reader to pick up on, but subtlety of personalities, of the underlying dynamics between characters. There is nothing subtle about a person on the far end of the spectrum of overt narcissism.

“And is it fair to say that narcissistic people actually aren’t very crafty, in a way?” I asked my friend, the next time we spoke.

She agreed. “In my experience, for the narcissist, there’s only now. Arranging this moment to maintain their superior self-image. There is no later.”

“It might be difficult to work someone like that into a mystery novel,” I said. “And make it feel . . . mysterious.”

“Exactly,” my friend laughed. “It’s not mysterious.”

Highly narcissistic people, while emotionally manipulative, often have too grand an opinion of themselves to think they need to be particularly diabolical. The narcissist believes everyone around him is pretty stupid. Lies, then, don’t need to be all that convincing. Whatever mess the lie creates later will be someone else’s fault anyway: It always is. It’s all about the creation and reaffirmation of the story of one’s superiority. As long as that delusion is believable to the narcissist himself, the plausibility of the supporting lies is irrelevant.

If I was to have such a character in my novel, obviously I would need to ask myself: Where was the subtlety going to come from?

My solution, eventually, was to focus most of my attention on my dutiful daughter character, Ivy. The challenge in subtlety was not in the presentation of the narcissist, but in the creation of a character so accustomed to the narcissist in her life that she didn’t view him as the reader might; that her perception of what is normal parental behavior is skewed. To be raised by a narcissist means being forced to abide someone else’s delusion. Narcissism itself is not complicated, but living with someone afflicted with it, trying to love or be loved by such a person, is. Especially for a young and vulnerable person.

It was a challenge to allow that the reader might notice the narcissism before the young narrator has the capacity to fully acknowledge it, and to go along for the ride with the narrator with sympathy, with a sense of dread. It was an experiment in dramatic irony. There is, of course, an untimely death in the book, but I tried to make some of the suspense come from the unfolding of such a fraught relationship. Sometimes the most terrifying investigations, after all, are the ones that bring us back to ourselves—to our long-held comforts and beliefs, to the people who instilled those in us, and to the secrets we didn’t know we were keeping.