Gilded Age Women Who Got Away With Murder

By Mariah Fredericks

April 17, 2020

She couldn’t have done it…

Nan Patterson

Nan Patterson was young, she was pretty. In fact, she was a Floradora girl, one of the celebrated lovelies in the Broadway smash of that name. She came from a good family; her father worked in the Treasury Department.

Surely, she couldn’t have killed a man.

When Caesar Young was found shot to death in a hansom cab in 1904, suspicion naturally turned to the young woman who had been sitting next to him at the time: Nan Patterson. Young was married, a gambler and he and Nan Patterson had been seeing each other. Miss Patterson insisted that the gambler had shot himself. Suicide out of despair that she was going to leave him.

However, the gentleman’s gun was still in his pocket. The police did not feel the angle of the bullet was consistent with suicide. The murder weapon was ultimately traced to a pawnshop where it had been sold just the day before to a couple that matched a description of Patterson’s sister and brother-in-law. Who had rather precipitously left town.

Nan Patterson was arrested and held in the Tombs. Her trial was a sensation, with the New York Times promising “plenty of the dramatic.” Patterson developed a habit of fainting before court appearances. She worried for her sister, who was called to testify. “I am not at all afraid of anything Midget said on the stand, but it made me nervous to see her so badgered.” Ultimately, the jury could not agree to convict. Afterwards, crowds shouted, “Free Nan Patterson! Set her free! Nan’s all right!”

There was another trial, and another, but Nan Patterson did go free. According to Patrick M. Wall in The Annals of Manhattan Crime. “The prosecutor concluded that no jury would unanimously believe that such a sweet young thing could commit so brutal a crime.”

Florence Carman

Mrs. Florence Carman was not a chorus girl. She was the wife of Dr. Edwin Carman, a respected figure in Freeport, Long Island. Unfortunately, she did not trust her esteemed husband with his female patients; even going so far as to hide a Dictaphone in his home office to record their encounters.

One evening, Mrs. Lulu Bailey arrived for an appointment with the good doctor. She was shot through the window of the house. Witnesses reported seeing a “woman in white” on the porch. A week after the murder, Mrs. Carman was arrested.

Like the Floradora murder, the Dictaphone Murder dominated the headlines. Reading the New York papers, you would have been quite unaware of the consequences of another murder—Archduke Ferdinand—playing out across the Atlantic. But the titillating proceedings ended in a hung jury, as the foreman announced that having deliberated for over thirteen hours, “it was impossible for them to come to any agreement.”

Mrs. Carman was retried in 1915, this time testifying on her own behalf. The press described her as soft-spoken, nervous. She admitted that she had suspected her husband of having relations with other women. She admitted she had been near the window when Mrs. Bailey was shot. And yet the jury acquitted her of murder.

Nan Patterson and Florence Carman weren’t the only Gilded Age ladies to get away with murder. In her report, Public Responses to Intimate Violence: A Glance at the Past, Carolyn B. Ramsey observes that in the late 1800s to the early 1900s, juries faced with women who had killed their partners often either voted for acquittal or a lenient sentence on the grounds of self-defense or because the women had been driven to murder through emotional or physical abuse. Ella Nelson was judged not guilty for killing her partner. Maria Barbieri was exonerated of slashing her lover’s throat. In his novel The Gilded Age, Mark Twain dramatizes this phenomenon in the story of Laura Hawkins who shoots the caddish Colonel Selby “…the public read from time to time of the lovely prisoner, languishing in the city prison, the tortured victim of the law’s delay; and as the months went by it was natural that the horror of her crime should become a little indistinct in memory, while the heroine of it should be invested with a sort of sentimental interest.”

It was men’s sacred duty to protect the gentler sex. And in the cases of Patterson, Carman, and others, rank sexism seems to have played out to their advantage.

These cases shed an interesting light on how women were viewed in the Gilded Age. As Professor Ramsey explains, Victorian and Progressive societies strongly adhered to the notion that women were frail, helpless children, ill-equipped to deal with life beyond the home. They could not even serve on juries, lest they become exposed to vulgar realities. It was men’s sacred duty to protect the gentler sex. And in the cases of Patterson, Carman, and others, rank sexism seems to have played out to their advantage. If a woman was driven to kill, the fact that she had resorted to violence—so unnatural to her sex—was proof in itself that she had been mistreated. (Of course, many times this was the case.) Any woman who would testify she had been ill-used could expect a receptive audience.

This indulgence did not extend to men who killed their partners—especially if they were poor. And it did nothing to prevent domestic abuse, to which the police were often indifferent. Tellingly, once women won the right to vote in 1920, compassion for the woman who killed markedly decreased. At the same time, public tolerance for spousal abuse by men increased; many agreed that sometimes women just needed a good smack.

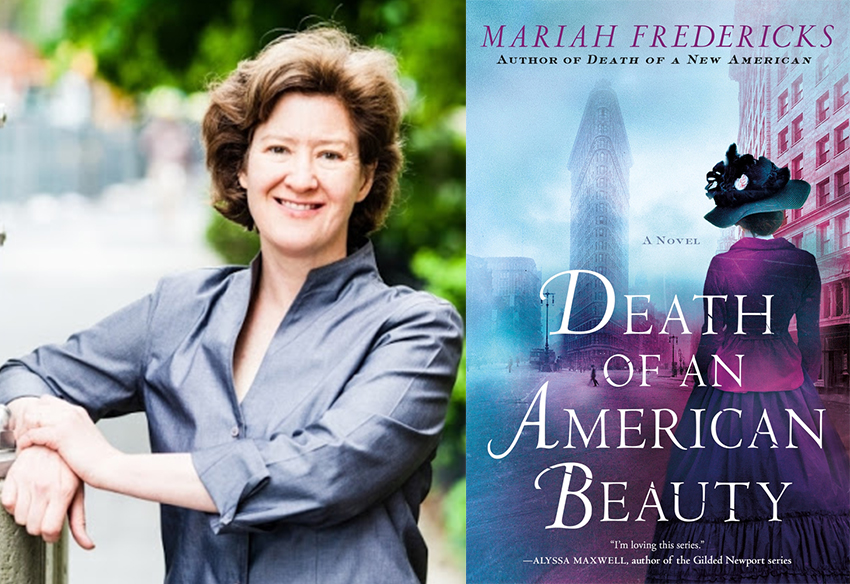

*Author Photo credit Jonathan Elderfield

Angie Barry’s Review of Death of an American Beauty

Mariah Fredericks’ Q&A on the Jane Prescott Series

About Death of An American Beauty by Mariah Fredericks:

Jane Prescott is taking a break from her duties as lady’s maid for a week, and plans to begin it with attending the hottest and most scandalous show in town: the opening of an art exhibition, showcasing the cubists, that is shocking New York City.

1913 is also the fiftieth anniversary of Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation speech, and the city’s great and good are determined to celebrate in style. Dolly Rutherford, heiress to the glamorous Rutherford’s department store empire, has gathered her coterie of society ladies to put on a play—with Jane’s employer Louise Tyler in the starring role as Lincoln himself. Jane is torn between helping the ladies with their costumes and enjoying her holiday. But fate decides she will do neither, when a woman is found murdered outside Jane’s childhood home—a refuge for women run by her uncle.

Deeply troubled as her uncle falls under suspicion and haunted by memories of a woman she once knew, Jane—with the help of old friends and new acquaintances, reporter Michael Behan and music hall pianist Leo Hirschfeld—is determined to discover who is making death into their own twisted art form.

Comments are closed.

It’s very good post which I really enjoyed reading. It is not everyday that I have the possibility to see something like this.

Thank you very much for these great cake recipes, I have learned a lot from your web blog

This website is amazing. There is interesting information.

Great article. Thanks for sharing this amazing piece of information.

I really appreciate this post. I have been looking all over for this! Thank goodness I found it on Bing. You have made my day!

Nice post. I was checking constantly this blog and I’m impressed!