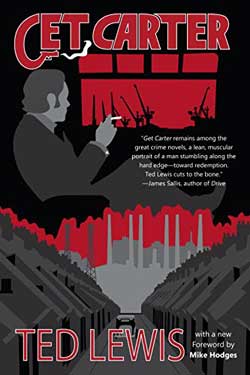

I’ll get right to the point here; Ted Lewis’s 1970 novel Jack’s Return Home (re-titled Get Carter so I’ll call it that from here on) is one of the most influential works of crime fiction in existence. In the world of U.K. hardboiled literature it’s had the kind of impact that books by Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler had on the genre in the U.S. In the new edition of Get Carter being put out by Syndicate Books, the back cover and inside pages contain jaw-dropping laudatory praise of the novel by the likes of Derek Raymond, Stuart Neville, Dennis Lehane, James Sallis, and John Williams, the last of whom says Lewis’s book is “the finest British crime novel ever written.” When I researched Lewis’s life and work several years back, one person I interviewed was David Peace; Peace told me, about Get Carter, “I very consciously used it as a blueprint for Nineteen Seventy-Four, my first novel.”

Ted Lewis’s 1970 novel Jack’s Return Home (re-titled Get Carter so I’ll call it that from here on) is one of the most influential works of crime fiction in existence. In the world of U.K. hardboiled literature it’s had the kind of impact that books by Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler had on the genre in the U.S. In the new edition of Get Carter being put out by Syndicate Books, the back cover and inside pages contain jaw-dropping laudatory praise of the novel by the likes of Derek Raymond, Stuart Neville, Dennis Lehane, James Sallis, and John Williams, the last of whom says Lewis’s book is “the finest British crime novel ever written.” When I researched Lewis’s life and work several years back, one person I interviewed was David Peace; Peace told me, about Get Carter, “I very consciously used it as a blueprint for Nineteen Seventy-Four, my first novel.”

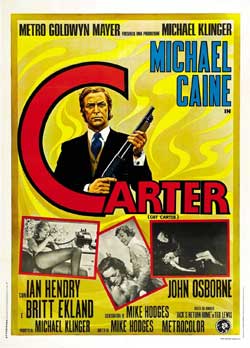

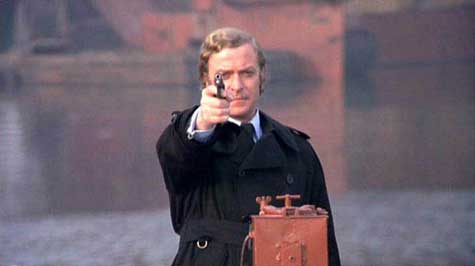

Before further discussion of the book, I’m going to pause and say a few things about the film that shares its title. Because you can’t say the words Get Carter without thinking of the 1971 big screen feature that stars Michael Caine and was directed by Mike Hodges (Hodges supplies the foreword to the new edition of the book). I’m not going to go into any detail about the movie, because a prolonged analysis or appreciation of it deserves its own space. Suffice to say that it is not only a classic film; it’s an institution. It holds high places on best-ever film lists issued by entities such as The British Film Institute, Empire magazine, Time Out, and The Guardian. If you’ve seen the movie, you likely don’t need me to try and convince you of its quality. If you haven’t, and if you care anything about film noir, gangster cinema, Michael Caine, or classic films period, just go watch it. If you’re like I was after my first viewing, when it’s over you’ll find you have a hankering to run it again.

Ok so back to Lewis’s novel. So what’s so great about it, why has it influenced so many? For me, it’s the layers. Taken at face value as a work of crime fiction, it is a supremely excellent example of such a book. It has everything lovers of noir lit want in their reads of that kind. It’s lean and mean, raw, gritty, unsentimental, and, like many of Lewis’s novels (there are only nine that were published, as he died of alcoholism-related complications at age 42), it jumps into a bracingly intense place in its very first paragraphs and remains in that fierce space throughout.

For those who haven’t read the book or seen the film, the story is about (and the novel is narrated by) Jack Carter, who’s the top enforcer for a London-based organized crime outfit headed up by two brothers (I have heard that Lewis was personally acquainted with the Krays). Jack is originally from northern England and his lone sibling, his brother Frank, never left their hometown in that part of the country. At the outset of the tale, all of which takes place over one long weekend, Frank has just died. Jack’s thoughts and feelings about his brother’s passing are no normal bereavement state, though. When Jack learns that Frank apparently perished in a drunk-driving incident in which he was on his own, he knows something’s amiss. Frank was always a careful, tidy, clean-living kind of fella, and the idea of him engaging in that kind of drunkenly reckless behavior is just too far-fetched for Jack to accept. Something else Jack knows is that the bar where Frank worked was owned by northern associates of Jack’s bosses. Jack assumes that the local syndicate from his hometown must have had something to do with what he believes was the arranged death of his brother. Against the wishes of his employers, who prefer that he not stir up trouble in the northern territories, he goes home to conduct a vigilante investigation. Jack quickly learns that he was right in what he assumed about Frank’s death, and when he gathers just how many tiers there were to the buildup that led to his brother being offed, how many unsavory characters were in on the plot, he has quite a lot of items on his revenge-fueled to-do list.

For those who haven’t read the book or seen the film, the story is about (and the novel is narrated by) Jack Carter, who’s the top enforcer for a London-based organized crime outfit headed up by two brothers (I have heard that Lewis was personally acquainted with the Krays). Jack is originally from northern England and his lone sibling, his brother Frank, never left their hometown in that part of the country. At the outset of the tale, all of which takes place over one long weekend, Frank has just died. Jack’s thoughts and feelings about his brother’s passing are no normal bereavement state, though. When Jack learns that Frank apparently perished in a drunk-driving incident in which he was on his own, he knows something’s amiss. Frank was always a careful, tidy, clean-living kind of fella, and the idea of him engaging in that kind of drunkenly reckless behavior is just too far-fetched for Jack to accept. Something else Jack knows is that the bar where Frank worked was owned by northern associates of Jack’s bosses. Jack assumes that the local syndicate from his hometown must have had something to do with what he believes was the arranged death of his brother. Against the wishes of his employers, who prefer that he not stir up trouble in the northern territories, he goes home to conduct a vigilante investigation. Jack quickly learns that he was right in what he assumed about Frank’s death, and when he gathers just how many tiers there were to the buildup that led to his brother being offed, how many unsavory characters were in on the plot, he has quite a lot of items on his revenge-fueled to-do list.

So there’s that about Get Carter: it is a finely written crime novel. But there are other commendable aspects of the book. One of these is its exploration of the relationship between Jack and Frank. That part of the story is just as much what really drives the book as Lewis’s close looks into the workings of England’s criminal underworld. If Jack simply loved his dear brother and was bitterly grieving over his set-up death, that would be one thing. But Jack’s and Frank’s siblinghood was actually far from wholesomely close-knit. The brothers didn’t get along, to say the least. Jack has always been rough around the edges and this didn’t sit well with the methodical, judgmental, aloof Frank. Here, let me shut up and allow Jack to tell you how it was between them:

Those were the best times I ever had as a lad. Just alone with Frank down on the river. But that was before he’d begun to hate my guts.

Not that I’d exactly been full of brotherly love for him before I’d left the town.

He’d been so fucking po-faced about everything. Siding with our dad all the time, although never hardly saying anything. He’d just let me know by the way he’d looked at me. Maybe that’s why I hated him sometimes: I could tell how right he thought he was about me.

All of the bad feelings between Jack and Frank elevate to a point of irreconcilable differences when it comes out, in their adult years, that Frank’s daughter might very well be Jack’s; Jack had a spontaneous, alcohol-induced foray with Frank’s fiancée not long before their wedding. The daughter, Doreen, is 15 at the time of Get Carter and she’s very much an integral part of the story. You get the sense that when Jack starts in on wanting to rub out the people who were responsible for his brother’s death, he’s actually attacking something deep in his own blackened heart. If there’s any fault at all to be found in Hodges’s film in comparison to Lewis’s book, it’s that the movie doesn’t fully explore the complicated relationship between the Carter brothers.

Another element of Get Carter that makes it such a remarkable book is its atmosphere. Lewis, who was a gifted visual artist, combined his considerable writing talent with his eye for graphic images, to pen some evocative passages that give the reader a clear optical sense of the setting and people who inhabit the story. Specifically, we see, hear, and smell the grim environs and sleazy denizens of Jack’s northern hometown. Or we see and feel experiences like his train ride from London to the town. Listen to him:

At first there’s just the blackness. The rocking of the train, the reflections against the raindrops and the blackness. But if you keep looking beyond the reflections you eventually notice the glow creeping into the sky.

At first it’s slight and you think maybe a haystack or a petrol tanker or something is on fire somewhere over a hill and out of sight. But then you notice that the clouds themselves are reflecting the glow and you know that it must be something bigger. And a little later the train passes through a cutting and curves away towards the town, a small bright concentrated area of light and beyond and around the town you can see the causes of the glow, the half-dozen steelworks stretching to the rim of the semicircular bowl of hills, flames shooting upwards – soft reds pulsing on the insides of melting shops, white heat sparking in blast furnaces – the structures of the works against the collective glow, all of it looking like a Disney version of the Dawn of Creation.

Finally, a facet of the novel that gives it much of its lasting strength is its view of time and place. In the foreword Hodges writes eloquently about this aspect of Lewis’s book. Through Jack Carter’s eyes we see that England at the close of the 1960s was not at all just bright colors and pop groups and a sense of the chance of prosperity for all. There was an underbelly to all of that and it was either thriving or remaining stubbornly alive through the era. Lewis handles this duality and those false facades by contrasting things like the “Walker Brothers haircuts” of some of the younger men, the “pop colours” to be found in illustrations at public places, and the band posters up in Doreen’s bedroom, with harsh descriptions of steelworks settings; offsets visions of the lavish surroundings being enjoyed by the northern gangsters who are prospering in their black market dealings, with descriptions of the seedy pubs from which they draw some of their income. And so on. Lewis’s/Carter’s outlook on all this is piercing, it’s unforgiving, and its relentlessness is so much of what makes Get Carter a seminal groundbreaker. Here’s Jack’s take on some of the people he encounters in a casino run by the head gang boss from the northern town:

I looked around the room and saw the wives of the new Gentry. Not one of them was not overdressed. Not one of them looked as though they were not sick to their stomachs with jealousy of someone or something. They’d had nothing when they were younger, since the war they’d gradually got the lot, and the change had been so surprising they could never stop wanting, never be satisfied. They were the kind of people who made me know I was right.

It’s interesting that Lewis, who was the son of a workingman (his father managed laborers at a rock quarry around their hometown of Barton-Upon-Humber, in North Lincolnshire) and who was a sensitive art college graduate, wrote so convincingly about gangsters, or that he even took up the challenge. Lewis’s first novel, All the Way Home and All the Night Through (1965), Get Carter’s predecessor in his personal canon, is a blatantly autobiographical work of coming-of-age literary fiction. Later in his writing career, Lewis revisited that same kind of terrain in authoring the similar yet superior 1975 novel The Rabbit, which is a classic of gritty English kitchen sink drama, on a par with titles such as Alan Sillitoe’s Saturday Night and Sunday Morning and Stan Barstow’s A Kind of Loving, etc. But there are clues to why Lewis chose to author Get Carter, which led to him writing six other crime novels over his short life. One is his love of Chandler, a love that seems to have been engendered in part by Lewis’s boyhood schoolteacher Henry Treece, a noted writer who had a large impact on Lewis’s life, and whom read Chandler to his students, using an American accent. Another hint is Lewis’s great love of cinema and particularly of shoot-‘em-up films; a college friend of Lewis’s told me about the countless hours they spent watching movies at the cinema in Hull where they went to art school together, and he mentioned that High Noon was a particular favorite of Lewis’s.

In a 1980 article in the Scunthorpe Evening Telegraph newspaper, a piece that was done on the eve of the publication of Lewis’s last (and, to my mind, best) novel GBH, and just two years before his death, Lewis had these things to say about Jack Carter and the first of his three novels centered around that character:

“I suppose the time was ripe for Carter,” and “You could describe Carter as an anti-hero. He has no redeeming features . . . But I used some license by giving him a sardonic and cynical sense of humour, which made his character more palatable to the reader.” Indeed. As is true of other Lewis novels, highly effective stinging humor is sprinkled throughout Get Carter.

Lewis had an encyclopedic knowledge of the history of cinema and he loved to play trivia games based on questions about the movies. His college friend told me that he dreamed of being a filmmaker. Naturally, such a person would be thrilled with the advent of his second novel being made into a major feature film starring Michael Caine. But for Lewis one part of Hodges’s adaptation always nagged at him: the northern locale. Although the town in the book is never named, Lewis meant it to be placed in his own home area of North Lincolnshire. The author, who lived in London and other parts of southern England during his post-collegiate and early writing life, and who spent his last years back in Barton-Upon-Humber, had a great attachment to his home turf. Some of the physical descriptions in Get Carter are based squarely on places in North Lincolnshire, just as several of the characters in the book are named after Lewis’s childhood friends from Barton-Upon-Humber. But Hodges had his reasons for moving the northern setting to Newcastle-Upon-Tyne (he explains in the foreword). And while it’s difficult to find any flaws in the backdrop of the film, Lewis never stopped wondering why it couldn’t have been shot in the place where he meant the story to occur. In that same newspaper article mentioned above he is quoted as saying, “Scunthorpe as a town is very interesting with its steelworks, one main street in the centre, and the rows of Victorian terraced houses. I thought it would have made a dramatic backdrop for the film. People are accustomed to seeing violence played out in spectacular locations, but to have set the film in Scunthorpe I believe would have been a good counter-point.”

Ok, so that’s my take on Get Carter. If you care to read my overview of Lewis’s full writing career, see this Hall-of-Famer post I did on him, it being my debut article for this site.

Comment below for a chance to win a copy of Get Carter by Ted Lewis. To enter, make sure you're a registered member of the site and simply leave a comment below.

TIP: Since only comments from registered users will be tabulated, if your user name appears in red above your comment—STOP—go log in, then try commenting again. If your user name appears in black above your comment, You’re In!

Get Carter Comment Sweepstakes: NO PURCHASE NECESSARY TO ENTER OR WIN. A purchase does not improve your chances of winning. Sweepstakes open to legal residents of 50 United States, D.C., and Canada (excluding Quebec), who are 18 years or older as of the date of entry. To enter, complete the “Post a Comment” entry at https://www.criminalelement.com/blogs/2014/08/get-carter-by-ted-lewis-crime-fictions-open-source-blueprint-brian-greene beginning at 2:00 p.m. Eastern Time (ET) September 18, 2014. Sweepstakes ends 1:59 p.m. ET September 25, 2014. Void outside the United States and Canada and where prohibited by law. Please see full details and official rules here. Sponsor: Macmillan, 175 Fifth Ave., New York, NY 10010.

Seen both films, loved Caine in both! Never read the book but if I win I could!

Great post! Excellent novel and Caine film, looking forward to rereading sequels.

Very excited that this is finally getting reprinted. However, the cover art is pretty underwhelming.

I’ve never read the book or seen the film, but I will now!

Great book … Great movie … Well deserving of all the praise …

What a cogent, well-written article. The film is great, the book sounds even better, but that’s usually the case.

Interesting info

Never saw the films but I sure do now after reading your post.

Excellent analysis.

Excellent analysis.

Your review of this book tells me I’ll have to read slowly to catch all the nuances! Usually I race through mysteries, and miss lots of the descriptive passages. I love dialogue and intrigue though, so perhaps this book will increase my ability to “pay attention.” Thanks for the thorough explanations .

I have seen the films and I would love to read the novel.

Please enter me.

Thanks!

I’ve seen the movie but can’t recall if I read the book. Look forward to reading Get Carter.

Would love to read the book

Would love to read this book

I would love to read the book.

Saw the movie years ago and lovedit. Now I would loved to read the book!

Get Carter to me! Yes!

While I like film noir, I don’t seem to be able to get into written noir as easily. I’ve read Chandler and others, but it takes longer for me to read that sub-genre than other crime novels of similar length.

Now I feel in the mood to watch this movie all over again as it’s been awhile since I watched it last!! Can’t wait to read the book as well!! Thanks for chance to win & good luck to all who enter!!:)

Great flicks. Would love to read this.

Would love to win the book and need to watch the movie. It’s funny but that movie is one I always come in on half the way through. I watch a bit and am intrigued but since it’s half over continue changing channels. Will look it up.

How have I missed this book? I have never seen the movie and now I believe I would rather read the book.

I would love to read the book and then see the movie with the marvelous Michael Caine.

This post makes the book sound intriguing and makes me want to read all of. His writings and see the movie if still available

LOVED the Caine movie, but I’ve never read the book. I’m not sure how I’ve missed it all these years.

I feel left out – not familiar with the book or movie. Will try finding the flick; hope to win the book.

Yes a classic, I’d love to read it!

My library has the movie, but not the book. Looks like I’ll have to get my own copy if I want to read it.

Greatly enjoyed the film versions (saw them in reverse order — first Stallone, then Caine), and never knew much about the book until now. Hope to read it someday soon.

Would love to win!

Would love to read – sounds great!

I barely remember the movie–must check it out. Wasn’t there a remake much more recently?

I’d love to read this thanks