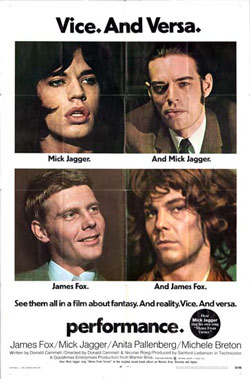

A tagline for Performance, released in 1970, described the movie this way:

A tagline for Performance, released in 1970, described the movie this way:

“This film is about madness. And sanity. Fantasy. And reality. Death. And life. Vice. And versa.”

It's a tagline of great accuracy. Few films have focused so obsessively on the idea of fusion. And no gangster film ever made unfolds quite like Performance does. It begins by plunging you into the East End London criminal underworld and the violent activities of a professional gangster named Chas (James Fox). For about half the film, you are immersed in his existence as an enforcer for a London gang. But when Chas, on the run after angering his boss, has to hide out, the film takes you into a completely different realm. This realm is a drug-filled bohemian household inhabited by the fading reclusive rock star Turner (Mick Jagger) and the rock star's two housemates Pherber (Anita Pallenberg) and Lucy (Michèle Breton). How these two polar opposites, the hard macho gangster and the fluid seductive rock star, affect and change one another, is the crux of the film.

Performance originated with Donald Cammell. Born in Edinburgh in 1934, he was a precocious child who was painting and drawing by the age of three. By the early 1950's, he was a successful society portraitist based in the affluent Chelsea section of London. Cammell could have continued in this vein indefinitely, but he chucked his burgeoning career as a society painter to pursue artistic satisfaction in the vibrant, more modern world of film. The 1968 heist film, Duffy, starring James Fox, Susannah York, and James Coburn, features a script by Cammell, but the final film was a far cry from what Cammell intended. The story revolves around two English brothers who with the help of the American hippy Duffy plot to rob their father. The original script centers around young Parisian hipsters and deals with crime, betrayals, and sexual escapades. In retrospect, the germ of many ideas that would sprout in Performance are in evidence. But Duffy became watered down during its filming, and Cammell's protests as his script got changed resulted in him being kicked off the set. A distasteful experience, to be sure, but one that made Cammell resolve to direct his own script the next time out.

He would wind up co-directing, though of his own volition. Armed with a treatment for Performance and partnered with first time producer Sandy Lieberson (who had been his agent), Cammell asked Nicholas Roeg to be his cinematographer. At this point Roeg was the foremost cinematographer in Britain. He'd worked on Roger Corman's Masque of the Red Death (1964), Truffaut's Fahrenheit 451 (1966), and Richard Lester's Petulia (1968), among others. Roeg said that he was now only interested in shooting films if he could also direct them, so Cammell suggested that he co-direct. Roeg accepted. And so even at a fundamental filmmaking level, Performance became an act of fusion, with two brilliant filmmakers, albeit novice directors, working as one.

Who contributed more, Roeg or Cammell? Who was the main guiding force behind Performance? The question is moot. Though Cammell, no question, came up with the idea and oversaw the script, he and Roeg wholly collaborated during the shooting. Cammell would deal with the actors and Roeg would concentrate on lighting and camera placement, but every night they would discuss the shoot, Roeg talking about the performances, Cammell about his visual ideas. As Colin MacCabe says in his book about the film, Roeg has described the shoot as “a sort of secret collaboration of our own brains”, a time when their “personal egos fused into one” and they were “so secretly close” and they “supported each other in manipulation.” Remarkable how much these descriptions sound like the relationship between Chas and Turner, two who also experience a merger of their minds and egos.

Performance was shot in 1968. In London during this time, Cammell moved socially in the city's two most exciting “scenes”. One was the criminal world dominated by the celebrity twin brother gangsters Ronald and Reginald Kray. Cammell didn't know the legendarily ferocious pair (front page material in Britain for years), but friends of his knew the Krays well and helped him write and shape the Performance script, adding underworld authenticity. The other area of great dynamism was the world of rock and roll, exploding then with its sense of danger and sexual abandon. Cammell knew Mick Jagger and Anita Pallenberg before casting Performance; they both were his friends and Pallenberg contributed also to the screenplay. Attuned to the energy of his time, Cammell had the brilliance and audacity to want to make a film that would unite these two charged worlds, transgressive worlds, and the more real life players, non-actors, he could get from each, the more authority his film would have.

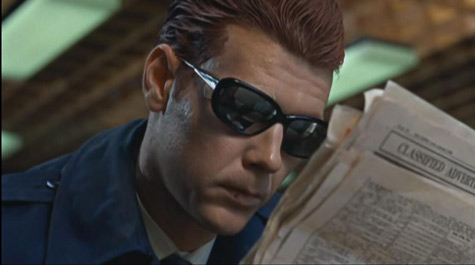

Paramount in creating this reality on the gangster side is the casting of Johnny Shannon, who plays Harry Flowers, the gang boss Chas upsets. Johnny Shannon was a former boxer who often hung out at the Thomas a Beckett pub in South London. James Fox found him there when he was researching the London criminal classes for his role and Shannon, though no criminal himself, introduced him to many of the criminal friends, “chaps,” he hung out with at the pub. Shannon helped coach Fox in the accent and manner of an East End gangster, and Cammell and Roeg, decided just before the shoot started to put Shannon in the movie. The result was a new representation of British crime on film. Before this, as many have pointed out, the most common picture of the London criminal came from fogbound Victorian-era villains. Fagin comes to mind, and the criminals in the Sherlock Holmes stories. But Johnny Shannon's Harry Flowers, modeled on Ronnie Kray, is late 20th century working class to the core and in your face about it. He's calm and assertive—not ashamed of his lower class background—and he knows how to use words. He emphasizes for Chas that Chas works not for him, Flowers, but for “the business”, and when describing the protection rackets he runs, he employs all sorts of circumlocutions to describe the violence his gang shells out. No need to be barbaric, even if he is in a rough profession. He's a thoroughly modern gangster, and as such, a figure that would influence scores of British cinematic gangsters to come, from Bob Hoskin's Harold Shand in The Long Good Friday to Ian McShane's Teddy Bass in Sexy Beast.

James Fox, of course, was a star before Performance, but he had mostly played upper class roles, a reflection of his real-life background. For his Performance research, he moved into a flat in the rough and tumble Brixton neighborhood, and during the day he would train with the boxers who frequented the gym above the Thomas a Beckett pub. It took time for the refined Fox to adapt to his new surroundings, but by the time the shoot began, he had the severe haircut and physique of his new criminal class acquaintances and even had taken to wearing suits from the gangsters' favorite tailor. He was Chas, the hard man, a frightener, somebody who puts “a little stick about” for his boss. Violence saturates Chas' world, violence pervades the first half of Performance. When in bed with a woman, Chas is rough; he destroys an establishment that has declined Harry Flowers' protection; he threatens a lawyer defending a man whose testimony could harm Flowers; he and his cohorts bound and gag the lawyer's chauffeur, then pour acid on the lawyer's car and use a straight razor to shave the terrified chauffeur's head. He does all this with a ferocity and even wit that shows a passion for his work, and it's clear to all who know him that he likes his job too much. He's described as a “right nutter” by one man and “an out of date boy, an old-fashioned boy” by another. Flowers himself calls him a “performer” and asks who in the hell he thinks he is, the Lone Ranger? “I know who I am,” Chas replies, an important comment in light of where the film will go. Chas has no doubts about himself as a man or where he stands in the world, but that all changes in the film's second half when he has to flee his gang after killing someone Flowers told him not to bother.

There's a Mars Bar on the stoop of the decrepit Notting Hill mansion Chas takes refuge in—this is a reference to the Redlands drug bust of 1967, when Jagger and Keith Richards were arrested and rumor had it that the police found Marianne Faithful with a Mars Bar inserted in her genital area—and inside the mansion, Chas finds even odder things. Indeed, no cinematic gangster has ever ended up in a hideout as strange (or as enticing?) as the one inhabited by Turner and his two beautiful housemates.

There's a Mars Bar on the stoop of the decrepit Notting Hill mansion Chas takes refuge in—this is a reference to the Redlands drug bust of 1967, when Jagger and Keith Richards were arrested and rumor had it that the police found Marianne Faithful with a Mars Bar inserted in her genital area—and inside the mansion, Chas finds even odder things. Indeed, no cinematic gangster has ever ended up in a hideout as strange (or as enticing?) as the one inhabited by Turner and his two beautiful housemates.

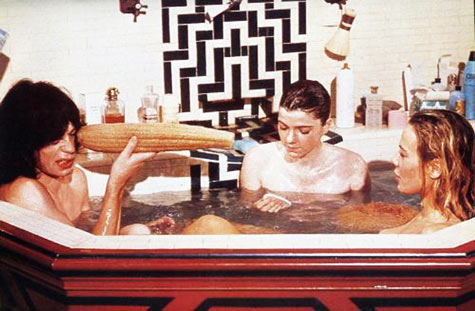

At first Turner is repulsed by his new surroundings: “It’s a right pisshole,” he says, with “long hair, beatniks, free love, druggers”. And Turner tries to return his rent money so that Chas, clearly not a bohemian type, will leave. But Chas starts to become intrigued by the sexual vibe permeating the place (the threesome scene between Jagger, Pallenberg, and Breton is one of the most erotic scenes you'll ever see in a mainstream film), and the powerful energy of the gangster comes to fascinate Turner, a rock star who ”has lost his demon.“ The hard man starts to soften, the androgynous man to harden, faces overlap. And Chas barely knows how to deal with the teasing and taunting and prodding of Lucy and Pherber. A man who could smash up betting parlors and fight his way out of an ambush is at sea with these two free spirits.

At first Turner is repulsed by his new surroundings: “It’s a right pisshole,” he says, with “long hair, beatniks, free love, druggers”. And Turner tries to return his rent money so that Chas, clearly not a bohemian type, will leave. But Chas starts to become intrigued by the sexual vibe permeating the place (the threesome scene between Jagger, Pallenberg, and Breton is one of the most erotic scenes you'll ever see in a mainstream film), and the powerful energy of the gangster comes to fascinate Turner, a rock star who ”has lost his demon.“ The hard man starts to soften, the androgynous man to harden, faces overlap. And Chas barely knows how to deal with the teasing and taunting and prodding of Lucy and Pherber. A man who could smash up betting parlors and fight his way out of an ambush is at sea with these two free spirits.

And like two true spirit guides of the era, they accelerate his transformation through drugs. Mushrooms, to be precise, and lots of them. The sight of a zonked Chas, decked out in a shimmering robe, a woman's wig on his head, with eyeliner on, is a far cry from the brutal picture of masculinity we saw in action during the film's first half.

What exactly happens at the film's end? That's open for debate. But one thing at least is clear. The film ends on a perfect note of synthesis. It's not that Chas has subsumed Turner or that Turner has subsumed Chas. The last face we see in the film indicates a hallucinatory merger.

Warner Brothers released Performance in 1970 but not before a monumental battle between the studio and the filmmakers. The first completed cut, presented to the studio in autumn 1969, outraged Warner's. The film's sex and violence, extreme for the time, bothered them, but what angered them most was that a movie starring Mick Jagger didn't show Jagger until halfway through the film. What was the point of having the rock superstar in the movie if for half the movie the audience had to sit through a revoltingly violent gangster flick? This cut was edited in London, and the studio refused to release it. They ordered a new edit and this edit would have to be done in Los Angeles, where they could more closely supervise it.

Neither Sandy Lieberson nor Nicholas Roeg could go to Los Angeles because both were about to start new projects (Roeg's was the film Walkabout, his first solo directorial effort). The news that the editing would be done in Los Angeles was ominous; it suggested endless studio meddling. But Cammell went to LA to recut the film and while there, though given a hostile studio editor to work with, he managed to find an editor he meshed well with, Frank Mazzola. He and Mazzola then proceeded to follow the studio's instructions—in a way. Ordered to speed up the film's first half and to get Jagger into the film earlier, they devised a method of very rapid cutting, something akin to William S. Burroughs' literary cut-up technique. Footage they had of Turner spray painting a wall in his house they interspersed in the film's first half, without any explanation. The superfast cutting they used lessened the amount of actual sex and violence on screen but only served to make the film more intense and radical. It's part of what makes the film still work today. Ironic, since these cuts would not have been done if the studio had accepted the original, more conventional cut.

(This promotional film highlighting Jagger's involvement was shown to Warner Bros execs and then to worldwide distributors.)

Also added in Los Angeles was the final layering of the soundtrack, arranged and partly composed by Jack Nitzsche. The ”Memo from Turner“ music video scene with Jagger singing was already in the film, but Nitzsche is the one who provided a new sound, the electronic synthesizer. The instrument as such didn't exist yet, but Nitzsche got access to a prototype and brought it to the recording studio to provide the film's electronic stings. They go perfectly with the film's editing style. But again, the studio's demand to bring the editing to Los Angeles to tone it down resulted in the film becoming more strange and challenging. Now you had a first half with realistic gangster violence edited for maximum, disorienting intensity and a second half full of mind games and sex play and also featuring casual drug use (Pallenberg injecting heroin into her derriere and calling it a ”vitamin shot“).

There would be still more struggles before the film got released, including the legendary test screening in Santa Monica in 1970, where one executive's wife supposedly vomited and the audience voiced its loathing so loudly the film had to be stopped and people's money returned. Warner's was sold at this time and a new studio head, John Calley, took over. He agreed to release the film. Still, the new Warner's president, Ted Ashley, despised it and wanted yet more cuts made. Finally Donald Cammell wrote a telegram to Ashley, and both he and Mick Jagger signed it. The telegram says that Performance is about ”the perverted love affair between Homo Sapiens and Lady Violence“ and adds that ”if Performance does not upset audiences then it is nothing.“ Hard to put it any better than that.

Some forty years on, Performance retains its ability to confound and disturb. Its editing techniques have been emulated by many, and of course lots of films since have had more extreme violence. But there is something about the film's authenticity that keeps it from dating, and its formal daring, the mixing of the gangster part with the sex/drugs/rock/psychological journey part, remains fascinating. This is a film I'm sure that Guy Ritchie, Quentin Tarantino, and many others who work in the crime/gangster genre have thoroughly studied, though it has none of the eye-winking cleverness of a Ritchie film and none of the ”this is a film about other films“ tone of Tarantino. It has an immediacy that makes you feel as if you are in 1968 London, a gripping quality of hallucinated reality. It is both a great British gangster film and a film that, as Marianne Faithfull said, ”preserves a whole era under glass.“

Bonus: follow this link for the full, psychedelically-fueled scene containing the song ”Memo from Turner.”

Scott Adlerberg lives in New York City. A film nut as well as a writer, he co-hosts the Word for Word Reel Talks film commentary series each summer at the HBO Bryant Park Summer Film Festival in Manhattan. He blogs about books, movies, and writing at Scott Adlerberg’s Mysterious Island. His Martinique-set crime novel, Spiders and Flies, is available now from Harvard Square editions at Amazon, B&N, and wherever books are sold.

Excellent piece! I’ve always loved this film. Good to see it spotlighted here.

Thanks, Brian. Glad you enjoyed the piece. Definitely a great and unique film.

Thoughtful article. This film haunted me upon its original release and continues to do so. I was a part of that gangster era and it was very exciting…