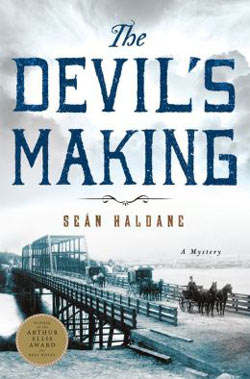

The Devil's Making by Seán Haldane, winner of the Arthur Ellis Award for Best Novel, features a Victorian-era Englishman who becomes a police constable in British Columbia, the ramshackle outer limit of the empire (available May 5, 2015).

The Devil's Making by Seán Haldane, winner of the Arthur Ellis Award for Best Novel, features a Victorian-era Englishman who becomes a police constable in British Columbia, the ramshackle outer limit of the empire (available May 5, 2015).

In 1868, Chad Hobbes has gone to sea armed with a thirst for adventure, an enthusiasm for all things Darwinian, and a maroon leather-bound journal his mother gave him. One hundred and forty days out of Portsmouth, bound for Vancouver Island, Hobbes is thoroughly sick of the voyage and his companions, particularly the rough-hewn captain of the Ariadne who has nothing but contempt for the colony of British Columbia and even less regard for his civilian passenger.

The youngest, virgin son of a parson—his wastrel older brother Henry is safely serving in the Army and still going to church as if he cares about the beliefs that Chad has discarded after sober deliberation—Chad knows he comes across a “niminy-piminy” to those older and more experienced, if not wiser. He hopes “the Colony” will cure him of his ignorance. He may publicly claim to be traveling to see the world, but actually, he’s looking to find himself.

But first he needs to find a job.

Chad soon learns that British Columbia doesn’t seem to have much more use for lawyers than the Captain of the Ariadne. The lack of jobs is underscored by Chad’s meeting with an old classmate who has fallen on hard times:

Poor Frederick, with a poor degree and always a bit dim, seems to have sunk rather than swum out here. Spent his money in the Cariboo, looking for gold. Now saving his meagre earnings in the hope of starting a private school some time in the future. From what he said of the recent fall in the local economy, this seems as unlikely a dream as finding gold. Like my own hopes of working in the law! As Frederick put it, rattling on, ‘No go, old chap, I should think. Even if you’d become a barrister before leaving England there wouldn’t be much work here. When people are caught red-handed in crimes they don’t bother with a legal defense. There are five or six barristers who flourished on all the litigation during the Gold Rush, when everyone was suing everyone else over land frauds and money, but they seem poor as church mice now. There are a number of solicitors too, but there isn’t the legal work, in conveyancing and so on, since there are so few sales.

Employment prospects look grim, but then a free-thinking colonist offers him a solution:

‘I have an idea for you.’ A dramatic pause. ‘But it will displease you at first. Did you notice any policemen in this town?’

‘Not so far.’

‘There are a dozen or so, under the direction of my friend the Stipendiary Magistrate, Augustus Pemberton. They keep the peace, and they look after the jail which is part of the courthouse on Bastion Street, and is also our lunatic asylum – an unsatisfactory combination. Now, I say to myself, why shouldn’t an educated young man like you, educated in the law, become a Constable?’ Another dramatic pause. ‘What do you think?’

‘I don’t see how…’

‘Of course. You’re a gentleman. Police Constables aren’t gentlemen. Correct? But if a gentleman cannot, at present, find other employment, why not become a Constable? After all, there are university men here in Victoria who work as assistants in shops. Others have degenerated and become drunken sots. A gentleman may fall very rapidly in a Colony. I remember one man, the Honourable So-and-So, who came out here in the Gold Rush with his man-servant whom he dismissed soon after their arrival for being impertinent. Two years later the Honourable So-and-So was reduced to the point where he had to take employment in a draper’s shop. The draper was his former man-servant.’

‘You mean I should become a sort of Bow Street runner? – a “Peeler”?'

And as simply as that, Chad becomes a Constable. And, as it turns out, he has a talent that’s worth more than all his expensive education reading divinity and jurisprudence back at Oxford. Not only does he have a naturalist’s eye for observation, like his idol Darwin, he’s a really good listener. And from the moment he steps onto the soil of the “New World,” people are just dying to tell Chad their stories.

When a murder occurs that has racial overtones and political consequences, it’s up to Chad to find out what the real story is, because everyone else seems satisfied with the narrative of their own prejudices.

This historical mystery, with its sharp observations on the divide between transplanted Victorian mores and New World realities, is enlivened by excellent period detail and a solid sense of place. Chad’s comments on the plantings of frost-blighted flowers, more suited to English gardens than the soggy Pacific Northwest weather, and his attempts to understand the mysteries of womanhood all become part and parcel of his experience finding himself by losing himself in the mystery he’s been tasked with solving.

More than anything else, what “sells” the story is Chad’s singular point of view as he records everything, not just in memory, but in that maroon leather-bound book his mother gave him. In the end, his thoughts on the differences between “civilized and savage man” elevate The Devil’s Making into genuinely literary territory.

To learn more or order a copy, visit:

Katherine Tomlinson is a former reporter who prefers making things up. She was editor of Astonishing Adventures Magazine and the publisher of Dark Valentine Magazine. She edited the charity anthology Nightfalls. Her dark fiction has appeared in Shotgun Honey, A Twist of Noir, Luna Station Quarterly, and Eaten Alive, as well as anthologies, including Weird Noir, Pulp Ink 2, Alt-Dead, Alt-Zombie, and the upcoming Grimm Futures, which she also edited. Her most recent collection of short stories is Suicide Blonde. She sees way too many movies.