Aside from a few times on airplanes, I don’t read books in a day. I started Hell on Church Street in the morning and before the clock rolled over to tomorrow, I was done.

Aside from a few times on airplanes, I don’t read books in a day. I started Hell on Church Street in the morning and before the clock rolled over to tomorrow, I was done.

I’ve admired Jake Hinkson’s writing for a while now. His short story Maker’s and Coke is one of the finest pieces of contemporary Noir I’ve read. He gets it. The pathos, the desperation, shadows that come off the page. And character. Hell on Church Street has that in spades.

It starts with a clever framing device that allows for two different narrators and entices us in with exchanges like this one:

“So what happened?”

“The story of my life?”

“Whatever.”

He shrugged. “The story of my life is I lived, I fucked up, and I’m going to die. I’ll probably go to hell.”

So, yeah, you know we’re driving down a dark road here. Webb, the main character, is the despicable son-of-a-bitch who is probably going to hell, but damn if you don’t end up enjoying spending time with the guy.

He’s a con man who has discovered the biggest con of all—religion in the south. Early on he lets his thoughts on the subject be known:

Nothing in my fifteen years would have served as proof of god’s existence, much less as proof of his love. I was underwhelmed by the fact that Jesus Christ of Nazareth had been executed by the Roman Empire two thousand years before my birth. One might as well say I should feel god’s love because John Wilkes Booth shot Abe Lincoln in the back of the head.

The particular southern town he has decided to practice his false prophet skills in sets him up with that classic spoiler of men—the preacher’s teenage daughter. Hinkson puts a delicious twist on it and creates a character in Angela who is not the Hollywood version:

She was not pretty, nor was she evocatively dressed. In fact, her drab green sweatshirt and long denim skirt seemed designed to make her as sensual as sheetrock. Was it that she was unattractive, that she was such easy pickings? That night I met other girls, pretty girls, and none of them moved me in the slightest. With her sad face and her bland clothing, this girl simply seemed more real to me. It’s safe to safe that she seemed more real to me at that moment than anyone else ever had in my life.

He falls for her and there begins his downfall. All this is early on and Webb explains with the most ominously Noir of statements:

Starting out I had good intentions.

From there, things spiral out of control in unexpected ways I won’t spoil. I thought, for a while, I had this book pegged but then it veered off into more deep dark woods than I anticipated, and that’s what kept me turning pages. The writing is so clear and so distinctly from Webb’s voice that it glides along like honey. The action picks up in shocking bursts of violence, but Hinkson keeps everything grounded in character. By the time the quicksand really takes hold of Webb, you’ll find yourself secretly rooting for him to pull out of the mess of his own making. Steeped in family and southern tradition, with the sweat-stained familiarity of an old baseball cap or a beat up pulp paperback worn out from time in a hip pocket, Hinkson keeps his story contemporary but his storytelling classic.

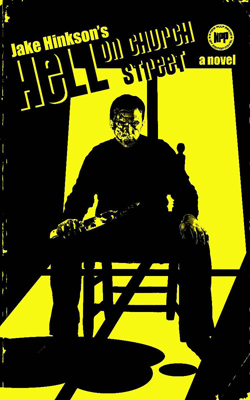

Hell on Church Street slotted right into my wheelhouse. It was dark in a Jim Thompson vibe but is more human. The sense of place and feel for character reminded me at times of the less gonzo of Joe R. Lansdale’s writing, like The Bottoms. Like an Arkansas swamp it is deeper than the surface implies, and there is something scary down in the muck.

Eric Beetner is an ex-musician, one time film director, and a working television editor and producer, as well as author (with JB Kohl) of the novels One Too Many Blows To The Head and Borrowed Trouble. He lives in Los Angeles with his wife, two daughters, and one really great dog. His upcoming novella Dig Two Graves will be out later this summer, along with short stories in the anthologies Pulp Ink, D*cked, and Grimm Tales.

Oh, that looks like a good un!

Eric, thanks for this fine review of Jake Hinkson’s work. I carried the torch for “Makers and Coke” to be the opening story in the Round One anthology published by Beat to a Pulp. If HELL ON CHURCH STREET retains the quality writing and emotional timbre of M&C, can an Edgar nom be far off?