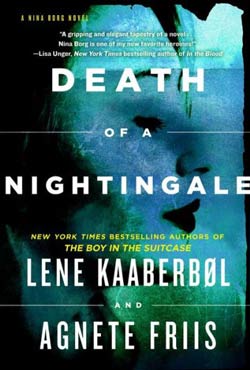

Death of a Nightingale by Lene Kaaberbøl and Agnete Friis is the third crime novel featuring Danish nurse Nina Borg (available November 5, 2013).

Death of a Nightingale by Lene Kaaberbøl and Agnete Friis is the third crime novel featuring Danish nurse Nina Borg (available November 5, 2013).

Sometimes it’s hard to tell a story. You have to think of a character. No, make that an interesting character (or at least a character who’s boring in an interesting way). And where does your character live? You know, setting. And what does your character do? Loaf around? Eat Nutella out of the jar and watch the wheels go round? Sorry to tell you that if you’re at the loafing, Nutella-eating stage, Kaaberbøl and Friis have you beat. They’ve lapped you.

Not only does Nightingale see the return of their popular series character, Copenhagen's Red Cross nurse and perpetual do-gooder-despite-the-significant-personal-costs Nina Borg, but there’s also a mother desperate to be reunited with her child; a Danish police detective on the trail of something bigger than he imagined; and his Ukrainian counterpart who shows up in Denmark under less than official circumstances. Oh, and then there’s the intricately woven, utterly compelling backstory set in mid-1930s Ukraine, under the reign of cheery Uncle Stalin. He’s just like your favorite uncle who comes for Christmas. Except Uncle Stalin sent people to Siberia.

What’s compelling about Nightingale—as well Kaaberbøl and Friis’s two previous installments, The Boy in the Suitcase and Invisible Murder—is that while it’s a character-driven story, it’s also social commentary. And a history lesson. And a multi-character-driven story. It’s hard to pull off one of these things well. It gets exponentially harder to pull off any of these things well in combination. When Natasha—whom readers will recognize from Suitcase and who is now accused of a double homicide and is on the run—thinks back to her first introduction to Denmark after leaving the Ukraine, it’s not a simple geography lesson:

In the little leaflet she was given, it said that Denmark was a democracy, and that there were more pigs than people living here, as if the two were somehow connected. On the way here, she had seen the great refrigerated trucks with pictures of grinning porkers on the side, and for some reason it made all the horrors fade a little then. As if nothing wicked could reach her here in this ridiculous little, flat Bacon Land, where even the pigs smiled on their way to the slaughterhouse. Back then the fence [around the camp] had seemed like a protection against the dangers she had run from. Even the most ordinary things—for example, the sight of the plastic chairs that were stacked every evening on the tables in the cafeteria with their legs up—brought tears to her eyes because it all seemed to ordered and calm. Even the fact that everything was so worn and nothing was clean for very long, even that was somehow reassuring—they weren’t in Kiev anymore, in the apartment’s traitorous luxury; it was more like [her hometown of] Kurakhovo and the smell of her childhood. [Her daughter] Katerina’s sheets were patterned with nice little Scandinavian trolls, and Natasha had an odd feeling of being at a summer camp with a lot of friendly people who were not out to kill her.

Obviously, Natasha has not been to the summer camp settings in any number of American gross-out (or horror, take your pick) films, but she makes an excellent point. Coal-House Camp, where she and Katerina lived (until Natasha was carted off to prison for attempting to kill the man that she was later accused of successfully killing), is a safe haven. And so, in a way, is Denmark. Even though terrible things happen here (this is, after all, a crime novel, and didn’t someone—William somebody?—once say something about Denmark being rotten?), there are good people. Sometimes, like Natasha, they make questionable choices, but it’s all part of a greater fight.

And Nina? As outrageous as it may sound, she’s like a killer a prosecutor might describe in his or her closing argument as someone who doesn’t care how many people get hurt in the commission of a crime, the kind of person where, under any circumstances, the ends justify the means. But for Nina, this is all internalized: she does not, cannot care how many times she gets hurt, flirts with death as long as she gets what she came for. Justice. Safe passage for those who cannot protect themselves. But please, remember this:

“What the hell makes you think,” [Nina] said, in her most glacial voice, “that I am anybody’s victim?”

See more new releases at our Fresh Meat feature page.

To learn more or order a copy, visit:

Jordan Foster grew up in a mystery bookstore in Portland, Oregon. She has a MFA in Fiction Writing from Columbia University, which she’s slowly paying off as the managing editor for BookTrib.com and by writing about crime fiction for Publishers Weekly. She’s back in Portland, where it’s nice and rainy and there are endless places to stash bodies. She tweets @jordanfoster13.

Read all of Jordan Foster’s posts for Criminal Element.

I love this premise, I’m getting this series!

I’d definitely recommend it. Start at the beginning!