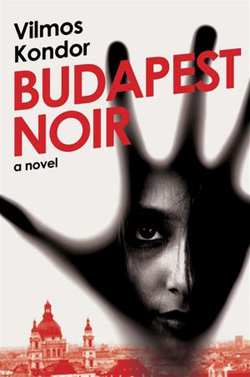

Budapest, October 1936. The Conservative Prime Minister is dead. The body of a young Jewish girl is found in a Terézváros doorway. Zsigmond Gordon, a criminal journalist for the Est newspaper, arrives on the scene soon afterwards and starts asking questions, but everywhere seems to run into a brick wall. The clues lead him upwards to the highest echelons of society and downwards to the lowest depths of misery and poverty. Gordon refuses to give up, keeps asking his questions, and the more they want to frighten him off, the more determined he becomes. He doesn’t know who to trust, and doesn’t know or care how many people’s interests he is harming. He just wants to find the girl’s killer, because, by the look of things, he’s the only one who cares.

Budapest, October 1936. The Conservative Prime Minister is dead. The body of a young Jewish girl is found in a Terézváros doorway. Zsigmond Gordon, a criminal journalist for the Est newspaper, arrives on the scene soon afterwards and starts asking questions, but everywhere seems to run into a brick wall. The clues lead him upwards to the highest echelons of society and downwards to the lowest depths of misery and poverty. Gordon refuses to give up, keeps asking his questions, and the more they want to frighten him off, the more determined he becomes. He doesn’t know who to trust, and doesn’t know or care how many people’s interests he is harming. He just wants to find the girl’s killer, because, by the look of things, he’s the only one who cares.

I’m always intrigued by historical mysteries, and by settings outside of those I’m familiar with, so the pre-World War Two Budapest Noir filled two niches for me immediately; that it’s also noir was just the cherry on top. (Can cherries be noir? Maybe if they’re black cherries?) The historical setting is full of precursors to World War Two and hints of future communist grimness, all perfect for noir’s themes of morality and justice, or the lack thereof. It’s full of characters dense with entrenched suspicions of each other, the law, and the government.

The novel’s hero, Zsigmond Gordon, is not a private investigator, but he is a journalist who specializes in crime. Gordon has the requisite Philip Marlowe-esque combination of cynicism and moral strength, and is in a position to investigate crimes through his contacts with the police. Throughout, his world-weary tone gives the feel of old-school detective novels.

Gordon only shook his head. “I don’t need a paper, son. I know the prime minister is dead.” I write the news, he thought, if, that is, the news lets itself be written…He couldn’t shake the thought of the Róna case. For days now his mind had been on nothing else; he found it impossible to believe that Erno Róna, a detective who had helped Gordon on his crime beat, was guilty.

… As the crime reporter at the Evening, Gordon knew the countless modes of death better than he would have wished. Maids drank ground-up match heads to poison themselves and flung themselves in front of trams. Barbers dismembered their lovers. Divorcees slashed their veins with razors. Tradesmen’s apprentices leaped off the Franz Joseph Bridge. Jealous civil servants cut their wives to shreds with butcher knives. Businessmen shot their rivals with revolvers. The possibilities were endless, and yet they were oppressively the same, for the end was always identical.

And, of course, there’s dark, or perhaps I should say noir, humor as well:

“The usual. Your beat. We found a girl.”

“What sort of girl?”

“What do you think? A dead one.”

Gordon’s character is doubled, almost, by Kondor’s portrayal of Budapest in the 1930s. The city is as much a character, a noir character, as Gordon. I could easily imagine seeing most of the scenes as movies, in black and white, with a soundtrack of mournful strings, and Gordon played by Humphrey Bogart.

Folding his copy of the Budapest Journal, he stood to pay the waiter and turned up his collar before stepping out onto Rákóczi Street. He glanced toward Blaha Lujza Square and noticed the neon lights of the newspaper building in the distance. He pulled a cigarette from his pocket and lit it…Dubious characters took their turns sidling up to him, trying to palm off a pair of silk stockings or some broad’s no doubt unforgettable services. Without stopping, Gordon chucked aside his cigarette butt and checked his watch. If he hurried, he might reach Franz Joseph Square on time. He could always catch a bus, but he enjoyed the hustle and bustle too much to consider public transportation.

I suspect readers who know Budapest and its history well will get a lot more out of this book; they will know more of the implications of the anti-Semitic prime minister’s death at the beginning of the novel, and how that death resonates politically and socially with the death of a possibly-Jewish murder victim. For example, the famous rescuer of Jews during World War Two, Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg, worked in Budapest. To me, the book offered an intriguing view of a time and place outside of my usual experience, and encouraged me to look more deeply into its history.

Victoria Janssen is the author of three erotic novels and numerous short stories. Her latest novel is The Duke and The Pirate Queen from Harlequin Spice. Follow her on Twitter: @victoriajanssen or find out more at victoriajanssen.com.

Sounds like this would be an interesting read.