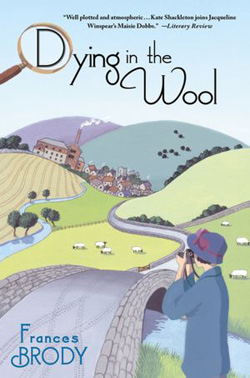

Bridgestead is a peaceful spot: a babbling brook, rolling hills and a working mill at its heart. Pretty and remote, nothing exceptional happens…

Bridgestead is a peaceful spot: a babbling brook, rolling hills and a working mill at its heart. Pretty and remote, nothing exceptional happens…

Until the day that Master of the Mill Joshua Braithwaite goes missing in dramatic circumstances, never to be heard of again.

Now Joshua’s daughter is getting married and wants one last attempt at finding her father. Has he run off with his mistress, or was he murdered for his mounting coffers?

Kate Shackleton has always loved solving puzzles. So who better to get to the bottom of Joshua’s mysterious disappearance? But as Kate taps into the lives of the Bridgestead dwellers, she opens cracks that some would kill to keep closed…

Chapter 1

Spinning the Yarn

My name’s Kate Shackleton. I’m thirty-one years old, and hanging onto freedom by the skin of my teeth. Because I’m a widow my mother wants me back by her side. But I’ve tasted independence. I’m not about to drown in polite society all over again.

Seven o’clock on a fine April morning, cosy under my blankets and red silk eiderdown. Through the open curtains I looked at the blue sky with its single small white cloud. In Batswing Wood, a blackbird sang. A crow alighted on my window ledge, head tilted, beady eye peering as I swung myself out of bed, planted my feet on the lambs-wool rug, stretching and curling my toes. Crow visitor turned tail, plopping a parting souvenir on the window sill.

Time to start the day. From downstairs came the sound of the letter box, first a rattle then a series of gentle thuds as post hit the mat.

As I brushed my teeth, a horse clip-clopped along the road towards Headingley Lane.

The back door opened. Mrs. Sugden would be at her self-appointed task. She would clank round with bucket and shovel, stepping along the little path to the road, and scoop up horse muck. Manure. Good for the roses, she says. Waste not, want not. But how much fertiliser does one garden need?

A small mountain of horse dung grows between the coal shed and the fence that separates the back garden from the wood. Resident armies of flies and bluebottles delight in its stench.

Knowing that some people, particularly my mother, hold my way of life and pastimes odd, I don’t like to interfere with Mrs. Sugden’s manure habit. For a reason I dread to fathom, my housekeeper has appointed herself horse muck monitor for the neighbourhood.

I live a short cycle ride from the centre of Leeds, not far from the university, and from the General Infirmary where Gerald once worked as a surgeon. Ours is the lodge house, sold off by the owners of the mansion up the road when the new occupants cut down on staff. A neat extension provides Mrs. Sugden with her own quarters, a situation which suits us both.

Because of the university and the infirmary, we have our fair share of soaring intellects in this part of the world, though I don’t count myself among them. My nose for solving mysteries comes from having a police officer father, a poke-your-beak-in persistence and an eye for detail.

Dressing gown round my shoulders, I sat on the bed and pulled on my stockings. Knees are a very strange part of the anatomy. Mine are too bony for my liking. As I contemplated my knees, I thought of the mystery I have not yet solved. My husband Gerald went missing, presumed dead, four years ago.

Like a sleepwalker, I allowed his and my family to persuade me into claiming insurance, transferring the house into my name, and drawing down his legacy. Financially, I am secure. I do the things we humans have devised to find some meaning in life. The sleepwalking is at an end, yet my world stays out of joint.

Try as I might, I have not yet been able to find an eyewitness to Gerald’s last moments, or to discover the circumstances of his death.

The only news of him, if you could call it that, can be summed up in a few words. Captain Gerald Shackleton of the Royal Medical Corps was last seen in the second week of April, 1918 on a road near Villiers-Bretonneux, following heavy bombardment. There had been gas in the valley and many casualties. Gerald had taken up position in a quarry, his stretchers and supplies stored in a large cave. He had written to me that there was so little he could do in a first aid post—just make the men feel better for having him there. A shell hit the quarry. His stretcher-bearers were killed and supplies destroyed. The few men that were left set off to walk to Amiens. I tracked down a lieutenant who spoke to Gerald on the road. The lieutenant said that there was barrage after barrage. Somebody must have seen Gerald again, just once. Somebody must know what happened.

Four years on, one side of my brain knows he is dead. The other side goes on throwing up questions.

It was after Gerald went missing that I began to undertake investigations for other women. I have uncovered some clinching detail about a husband or son, some eyewitness account from a friend or comrade. As late as 1920, I tracked down a soldier who had lost his memory, and reunited him with his family. One officer I traced last December remembered only too well who he was and from where he hailed. He had simply decided to turn his back on family and friends and begin a new life in Crays Foot, cycling to work each day at the Kent District Bank.

I wake in the night sometimes, startled, with the sudden thought that Gerald may still be somewhere on this earth – not dead but damaged and abandoned.

Searching for people and information, sifting through the ashes of war’s aftermath, drew me deeper into sleuthing. Where I failed for myself, I succeeded for others. It’s something useful I can do.

The enticing aroma of fried bacon drifted up the stairs, snuffing out my reverie and propelling me towards the wardrobe.

Opening the wardrobe door makes me groan. I can pounce on something wonderful, like the pleated silk Delphos robe, my elegant black dress, stylish Coco Chanel suit and the belted dress with matching cape that you can’t get a coat over. These outfits are squashed by pre-war skirts, shortened to calf-length, divided cycling skirt, and the shabby coat I wore when setting off with the other Voluntary Aid Detachment women and girls from Leeds railway station back in the mists of time. Fortunately I have several afternoon dresses. Mrs. Sugden and I peruse the ‘Dress of the Day’ in the Leeds Herald. She can make a fair copy of almost anything and I am an excellent assistant.

I pulled on my favourite skirt and took a pale-green blouse from the drawer, vowing to shop this very week and become highly stylish. I topped off my outfit with a short military-style belted jacket. To go downstairs in anything less substantial would draw Mrs. Sugden’s warning to ‘Never cast a clout till May goes out’.

Glancing in the mirror, I brushed at my hair. Before the war, I wore it long. In some ways long tresses made life easier, except on bath night, but I shan’t grow it again. If hair could speak, I suspect it would express a preference for length. It takes against me and has to be forced with water and brush into lying down.

After breakfast at the kitchen table, I poured a second cup of tea and reached for the post.

Mrs. Sugden busied herself at the kitchen sink. She has a look of Edith Sitwell, with the high forehead and long nose people associate with intelligence and haughtiness. She turned her head and primed me in her usual fashion. ‘You’ve only two proper letters. One from your mam.’

It would not amuse my mother to be called ‘your mam’.

I slit open my mother’s letter first because it would be bound to contain instructions of some kind.

Mother reminded me that she had booked our railway tickets to London for 11 April, a week on Tuesday. I like Aunt Berta and wouldn’t want to miss her birthday shindig. She and Uncle Albert live in Chelsea, in a house that expands as you enter.

‘Don’t bring that same black dress,’ Mother wrote. ‘You have worn it for the last three years. And before you say you will wear the Delphos robe, don’t forget who passed it on to you and that it is practically an antique. We will shop in London but before that I will catch the train to Leeds this coming Monday. You and I will visit Marshalls for an evening gown. It is time for a burst of colour.’

I’m sure there must have been a time when I liked shopping for clothes. Hmm, Monday. Today was Saturday. It might not be so bad. I could do that. Would have to do it. Yet . . . I might as well admit now that my aversion to buying a new evening gown is compounded by the totally illogical feeling that if Gerald does by some miracle come back, and we go out to celebrate, I ought to be wearing something he will recognise. I know that makes me irrational and a suitable case for treatment but there it is.

The brown envelope held my application form for the 1922 All British Photographic Competition, closing date 30 June. I have been a keen photographer since Aunt Berta and Uncle Albert bought me a Brownie Outfit for my twentieth birthday. I still remember the delight in cutting the string, folding back the brown paper, opening the cardboard box and discovering item after item of magical equipment. There was the sturdy box camera, ‘capable of taking six 31/4 x 21/4 inch pictures without re-loading’, the Daylight Developing Box, papers, chemicals, glass measuring jug and the encouraging statement that here was ‘everything necessary for a complete beginner to produce pictures of a high degree of excellence’. I subscribe to the Amateur Photographer magazine and occasionally attend the slide shows and discussions of the local club here in Headingley but have never yet entered a competition.

‘I think I shall enter this photographic contest, Mrs. Sugden.’

She peered over my shoulder as she picked up the teapot. ‘Why shouldn’t you? You’re at it often enough. Just don’t ask me to pose.’

She made a dash for the kitchen door, as though I might whip out a camera there and then and tie her to a chair.

With almost three months to the closing date, I would have plenty of time to choose a really good print of one of my old photographs, or to find a new subject. Most of all I like taking photographs of people, people absorbed in doing something, or just being themselves.

Through the window I watched Mrs. Sugden empty the teapot. She does not tip tea leaves on her dung heap; that must remain pure. What a challenge it would be to photograph a pile of manure danced on by flies and bluebottles and to do it so vividly and with such art that viewers of that picture would pinch their nostrils. Perhaps not.

I left the fattest letter until last.

Tabitha Braithwaite has a neat, sloping hand like a schoolgirl’s. She gives letter Ls a generous loop. An amateur analyser of handwriting might say she was a generous person, and that would be true.

Her missive covered several sheets, the handwriting becoming larger with each page. As I read it, I forgot to breathe. Our paths had crossed twice during the war, when we were with the Voluntary Aid Detachment. Since then we had met at the opening of the Cavendish Club in Queen Anne House. We were both huge supporters of a club for VAD women in London. Since then we had exchanged letters at Christmas. It must have been in one of my letters that I told her about my sleuthing and the success I have had in finding missing persons.

I had no idea Tabitha had carried such a burden all this time. Not once had she breathed a word about her own personal anxieties and her loss. The gist of her letter was this: her father went missing in August, 1916, a month after her brother was killed on the Somme. Now she is about to marry, and has this great desire that is sending her half-mad. She has a picture in her mind of her father, walking her down the aisle. The wedding will be on Saturday, 6 May at a church in Bingley.

I read the letter again, searching for an explanation as to why she had waited over six and a half years before deciding to instigate a search for her absent parent. Of course, that word came up, that little three-letter word that speared us all. War. But Mr. Joshua Braithwaite was a civilian, master of a mill.

The war slowed down normal life. In peacetime if a man went missing, boulders would be rolled back to find him. In wartime, men without uniform seemed less important. Mr. Joshua Braithwaite should have been an exception. Between the lines of her letter, I sensed a feeling of shame attaching to the situation. This would explain her reluctance to talk about it.

Mrs. Sugden came back into the kitchen and rinsed the teapot under the tap. ‘Anything interesting, madam?’

She calls me madam when she is being nosy. I swear she senses when I have a new case about to begin. She can be a great help and is the soul of discretion.

I heard myself sigh. The letter troubled me. ‘It’s a request for help,’ I said quietly. ‘Sounds like an impossible situation.’

Mrs. Sugden pulled out the chair and sat down opposite me. She leaned forward, folding her hands.

‘It’s from a Miss Braithwaite. We first met at a hospital in Leeds during the war, then again in France.’

I couldn’t call Tabitha Braithwaite a great chum as we didn’t know each other all that well, but what we’d been through gave us a special bond. ‘It’s about her father, a mill owner who disappeared in 1916.’

For once, Mrs. Sugden didn’t try to read the letter upside down but gazed at me with that look of piercing sympathy that makes me wonder who she lost as a young woman. I have never asked.

Mrs. Sugden’s eyebrows lifted the high forehead into a thoughtful crease. ‘And after all this time she wants you to find him?’

I looked again at the last page of Tabitha’s letter. ‘Yes. But that’s not all. She wants to engage me in a professional capacity. To reimburse me for expenses incurred she says, and to pay above my usual rate because of the short notice.’

For a moment, Mrs. Sugden and I sat in stunned silence. I have helped relatives search out missing persons as a kindness, not a paid service. I could not decide whether to be thrilled, terrified or insulted by the offer of money.

To save Mrs. Sugden the strain of upside-down reading, I turned the letter towards her. Frowning, spectacles perched low on her nose, she read. Her thin work-worn fingers, nails ridged with age, turned the pages slowly. She is a fast reader as a rule, devouring novels and exchanging sensational paperbacks with a vast network of female book lovers across Headingley and Woodhouse.

When she had turned over the last sheet, she bit her lower lip as if to aid thought. ‘Well then, at last someone’s doing the right thing.’

‘Searching for her father?’

She pushed the letter back to me across the table. ‘That an’ all. But it’s her offering to pay you for your trouble that impresses me. You’re recognised. You’re making a name for yourself.’

‘It’s only because she knows me.’

‘And knows how you come up trumps.’

What bad timing. I would love to help Tabitha Braithwaite, but with Mother’s shopping expedition, and the following week off to London, it just couldn’t be done.

‘I read something of this case at the time.’ Mrs. Sugden’s memory never fails to impress. She mops up newspaper stories like a blotter dabs ink. ‘Wasn’t he one of them Bradford millionaires?’

‘Not exactly Bradford is it? The Braithwaite mill is in Bridgestead, between Bingley and Keighley.’

She made a dismissive gesture. ‘Same difference. It’s all out in that direction.’

‘What do you remember about the case, Mrs. Sugden?’

‘It’s a long time back. A lot’s happened in the last six years.’ She took off her spectacles and polished the lenses on her apron. ‘I do recall my surprise that a man such as Mr. Braithwaite should get hisself in bother.’

‘What kind of bother?’

‘You couldn’t get a proper tale out of it. Just the feeling that there was more to it than met the eye. I do recall it was around the time of the tragic explosion at Low Moor. A cousin of mine was one of the firemen who lost his life.’

She picked up the morning paper and slapped it down in annoyance. ‘Look at that. Just look at that.’

Her bony finger accused an item headed “The Varsity Boat Race Name the Crews”. ‘Typical,’ she said. ‘They can name a bunch of young rowers, but did they name my cousin and the other firemen who lost their lives? They did not. Didn’t even say where the explosion happened.’

‘We had censorship. You couldn’t read a weather report, in case it helped the enemy.’

‘Dozens of working people lose their lives, no names no pack drill. One toff goes off the rails and we hear about that all right.’

If Mrs.. Sugden could edit The Times, she would make it very clear what was news and what was not.

She opened the kitchen drawer. ‘But if the lass wants you to find her dad . . .’ Rooting among the bottle openers, string, tape, sealing wax and tape measures, she found a jotter and a stub of pencil. ‘I better scratch out details of where you’re going. Just to be on’t safe side. No doubt your mam’ll be turning that telephone red hot.’

‘I don’t see how I can help Tabitha, at least not before her wedding. She’s getting married in . . .’ I consulted the letter. ‘Five weeks.’ I watched Mrs. Sugden copy down Tabitha Braithwaite’s address and telephone number. ‘Obviously I’d like to help her. But people must have looked for him at the time. The trail will be stone cold.’

What I didn’t add was that it terrified me to be thought of as a professional sleuth, accepting payment and expenses. Now I half regretted boasting to Tabitha that I traced the errant officer to the Kent bank when a professional investigator had failed.

It would be fraudulent to take money from Tabitha. I’m not a proper investigator, just stubborn, and sometimes lucky. My usual contacts for tracing missing soldiers were through the regiments. Officers and men were always willing to help. This was different. Yet the challenge of Tabitha’s request pleased me. If I could find out what happened to Joshua Braithwaite, a civilian with no regimental links to exploit, a trail gone cold, it would be a real achievement. It might change me in some way. I’d have an entitlement, would earn respect. As it is, I’m a sort of lady bountiful of the dead end. The person a wife or mother turns to when she does not know how to find something out for herself, or when all lines of enquiry turn cold.

So why shouldn’t I take on a difficult task and accept money?

It might at least excuse me from short-notice dress-shopping trips.

Mrs. Sugden raised her high forehead, creating a perfect set of horizontal lines. ‘You’ve said yes already.’

‘No I haven’t.’

‘I can see it in your eyes. You can’t resist.’

I tucked Tabitha’s letter into the inside pocket of my jacket. ‘It won’t hurt to look into it. Since you remember reading about Joshua Braithwaite in the newspaper, I’ll go to the Herald and see whether I can unearth that article you mentioned.’

And any others that there may have been, I thought to myself. I would grab a notebook, and cycle to the newspaper offices. Touch of swift pedalling and I could be there in twenty minutes.

Mrs. Sugden brightened. She likes me to be out of the way for an hour or two. It leaves her free to lavish attention on the dung heap, which receives the contents of her chamber pot.

‘What do I say if your mam rings?’ she asked.

Chapter 2

Man in a Homespun Suit

I cycled onto Headingley Lane. No one had told the month of March to skedaddle and give way to April. A chilly gust blew against the back of my neck, so cold it tickled. Sails on a bicycle would be a good idea, to be hoisted in a favourable breeze, providing extra power.

On Woodhouse Lane, by the edge of the moor, a telegram boy took it into his bonce to race me. For a while we were neck and neck, earning a curse from the rag and bone man we overtook. That curse slowed me down, but not the boy. He streaked ahead before pulling in front of me, daring me to brake or swerve. He turned his head, raising his too-small cap and grinning at me like a gargoyle. I waved defeat.

Go on, spotty lad. Something has to cheer your day before you end up under a tram.

I slowed down at the top of Albion Street. Sandwich boards on the kerb, and posters in the window proclaimed the day’s headline news. “Irish Bill Becomes Law—Mr. Churchill and the New Agreement.”

All of a sudden, I had misgivings. The folly of my mission seeped through me, like when you have sat too long on a damp stone during the break in a walk and not realised until you arise that your skirt is wet. I would need to be discreet about my enquiries. Tabitha would not thank me if some reporter guessed my task and her father’s story found its way back into print.

The doorman suggested that I park my bicycle round the back of the building. I wheeled the bike through an alley to a flagged yard where men in shirtsleeves and waistcoats were heaving tied bundles of the second edition onto a bogie to be pushed through the alley, ready for loading and delivery to the sellers and newsagents throughout the city.

I leaned my bike against the railings and made my way to the front office. A florid-faced porter chewed his pencil over a diamond-shaped crossword puzzle. He didn’t look up, having that air of regarding the general public as too much trouble altogether.

If I were a bona fide investigator, I would have a card and some justification for poking my snitch in.

‘Hello. I’d like to see copies of the newspaper from the summer of 1916 please.’

‘Public library, madam.’ He did not look up.

‘I want to buy some back copies.’

He chewed on the pencil, as he raised his eyes and gave me a cool glance. ‘If you want to buy a back copy, you have to know the date.’

‘I’ll know the date when I’ve looked for what I want.’

‘Public library. Our library here, it’s the company’s archive, for access by the reporters.’

I knew very well that I could consult papers in the public library, but hoped that somewhere during the course of my visit I might be able to dig out that extra revealing titbit of information about Joshua Braithwaite.

I did a Mrs. Sugden and read one of the porter’s crossword clues upside down. ‘Are you stuck on 4 across?’

His eyes met mine, with a hostile glare.

What was the matter with him? Perhaps he’d got out of the wrong side of bed, or didn’t like women. I pressed on regardless, saying somewhat apologetically, ‘I’m a bit of a crossword fan myself.’

We had to solve four clues together before he melted a little. I took advantage of the crack in the ice to push him a little further.

‘I’m researching for a friend who’s writing a play set in the summer of 1916. I need to get some local flavour of what was going on, just for background, and to take him some newspapers to have handy.’

The lie sounded reasonable enough to me, and also to the porter. He put down his pencil.

Pushing my advantage, I smiled sweetly. ‘My playwright friend says how the press is our country’s fifth estate, neglected at our peril.’

‘True enough,’ granted the porter. He lost his slouch and sat upright.

‘I expect you’re regarded by your friends and family as something of an expert on current affairs?’

‘There’s summat in what you say,’ he said in a wistful voice that made me think there was no truth whatever in what I said. ‘No one but the editor and the printers see the headlines afore I do.’

‘And you’re the gatekeeper for this great newspaper. In medieval times, you’d have worked the portcullis.’

I’m sorry to say that resorting to smarmy flattery is not a new skill. A detective’s card might eliminate such a requirement.

A light went on in his eyes. ‘I know who might be able to help you.’

‘I thought you might.’

‘Our Mr. Duffield.’

Five minutes later, the porter returned with a courtly gentleman, aged about sixty, wearing a well-boiled white shirt, a dark-green silk bow tie that would not look out of place on a stage magician, a worn tweed jacket and baggy flannel trousers. Corpse-white of skin, he had a mane of suspiciously black hair that swept his forehead like the rush of an incoming tide.

He extended a hand in greeting. ‘Eric Duffield, newspaper librarian.’

‘How do you do, Mr. Duffield. Kate Shackleton.’

‘I remember you from a benefit do at the Infirmary. Dr Shackleton’s widow. Superintendent Hood’s daughter.’

I felt myself blush, with both pleasure and annoyance. For once, couldn’t I simply be Mrs. Kate Shackleton?

Mr. Duffield smiled, showing a tombstone row of yellow fangs. ‘Well then, Mrs. Shackleton, if you’ll come this way we shall see whether the Herald may be of service to the daughter of the West Riding Constabulary. You’re researching for a playwright I understand?’

Did I detect disbelief? Possibly. I muttered something that sounded like agreement.

Mr. Duffield escorted me without further words along a corridor with offices to our left, and on to a still narrower corridor leading to a lift. On the second floor, the lift creaked to a stop. We stepped onto the landing.

‘Have you worked here long, Mr. Duffield?’ I asked as he led the way to a pair of heavy double doors.

‘Thirty-five years, starting out as office boy.’

‘You were not attracted to reporting?’

‘Far too frenetic an activity for me, Mrs. Shackleton. I prefer to dwell with the ghosts of yesterday’s stories.’

The large room was full of shelves stacked with binders, along the walls and across the centre of the room. Under the high windows were a couple of old oak tables and straight-backed chairs. The librarian took pride in explaining his index system, then turned to me with a penetrating glance. ‘What precisely interests you?’

I wanted to ask him did he remember the case of Mr. Joshua Braithwaite of Bridgestead. It would save me time but I did not want to risk bringing the Braithwaite case to public attention.

‘Really, it’s more background than specifics. I’d like to see copies of the paper for July and August, 1916, please.’

I chose a spot at the woodworm-eaten table under the high window. After a couple of moments, Mr. Duffield returned, bearing a heavy binder, and placed it with a thud on the oak surface.

I opened the binder and began to look at the newspapers, reading of Bradford City Council’s debate on the government’s appeal to postpone the August Bank Holiday, which did not meet with approval from the people of Bradford. I read of war honours, air raids, the Wesleyan conference, wages in the dyeing trade and the death toll in the Canadian forest fires.

The story appeared on Monday, 21 August. It bore no relation to the information in Tabitha’s letter. Under the heading “Mill Owner Saved by Boy Scouts”, the article read:

Mr. Joshua Braithwaite, 50, respected mill owner of Bridgestead, was saved from drowning on the evening of Saturday, 19 August by intrepid boy scouts. A first-rate troop under the leadership of Mr. Wardle was camping out in Calverton Woods.

At about five p.m., three bold lads strode to Bridgestead Beck to fill their billy-cans. They were surprised to see Mr. Braithwaite, a teetotaller and stalwart of Bridgestead Chapel, lying unconscious in the water. It is thought that Mr. Braithwaite suffered a dizzy turn while out walking.

The younger of the scouts ran to raise the alarm. Two older boys showed great presence of mind in pulling Mr. Braithwaite to dry land. Thanks to the speedy intervention of the resourceful young chaps, Mr. Braithwaite was brought to himself. In a weakened state, he was carried on a makeshift stretcher to the home of the local doctor who insisted that he remain there overnight, under close observation. Mrs. Braithwaite was sent for and hastened to be at her husband’s side where she remained through a night-long vigil.

I made notes, not wanting to ask for a copy of the paper and reveal my true interest. There was nothing in the following day’s paper. My hands were now black with printer’s ink. I turned to 23 August. There was the piece about the explosion “at a munitions factory in Yorkshire” that had so annoyed Mrs. Sugden because of its lack of detail and failure to mention her cousin. It was issued by the Press Bureau, authorised by the Ministry of Munitions, and seemed to me a fair account. 24 August. Still nothing more about Braithwaite. To keep up my pretence of being generally interested in the whole of summer 1916, I made random notes about the King’s surprise visit to soldiers in France, the extension of government control over the wool and textile trade, and why there is no substitute for Horlick’s malted milk.

Immersed in his index cards, Mr. Duffield looked up as a young messenger boy brought in more papers, placed them on the counter and beat a hasty retreat. I wondered whether the librarian ever felt overwhelmed by the sheer weight of cataloguing everything that ever happened.

‘Find what you wanted, Mrs. Shackleton?’

‘May I see September please?’

For the whole month of September, there was no reference to Mr. Joshua Braithwaite. I closed the binder.

‘You look puzzled,’ Mr. Duffield said as I stood up to go.

‘Strange what counts as news,’ I said, ‘and how some stories don’t appear at all and others peter out. I suppose editors were so very preoccupied with the progress of the war, and sensitive about what not to say.’

‘You’re thinking of the munitions explosion,’ he said gravely.

I was not, but chose to agree with him. ‘Yes, a big explosion like that in which so many people lost their lives.’ Mrs. Sugden would be glad to hear herself quoted as if she were scripture. ‘All those firemen dead in the course of their duty, and not a pip of acknowledgement.’

‘We did have one reporter who picked up on the Low Moor story. He wrote a good account as I remember, but it was spiked. The editor could only use official sources. The reporter gave me a copy. If you leave me your address I’ll look it out and send it on to you.’ Mr. Duffield looked entirely satisfied with himself having, as he thought, sniffed out the true subject of my interest.

It suited me to let him think that he was right. ‘The reporter won’t mind?’

‘He’d be delighted. Poor chap died in 1917—apoplexy if you ask me, fury at wartime censorship and not being allowed to do his job as he saw fit. He covered that area around Bradford and Keighley.’

‘Thank you. I’d like that.’ I took a deep breath and put on my most throwaway voice, with only a touch of interest. ‘I expect he wrote up that strange story about the mill owner, dragged from Bridgestead beck by boy scouts.’

He frowned, as though trying to remember. ‘Ah yes. That was a rum do. That was August too—and usually such a quiet month on the domestic front.’

We stood by the table. He turned to the article about Joshua Braithwaite and scanned the piece, running fingers through his black hair. If the dye came off, it would blend with printing ink. He struck me as a complex man. The dramatic green silk bow tie indicated a devil-may-care chap who did not mind what others thought of him. The dyed hair suggested something contrary, vanity or a desire to fit, not to be thought too old for the job.

He looked up from the article. ‘Will this stay within these four walls, Mrs. Shackleton?’

‘Of course.’

‘We didn’t hear any more about Mr. Joshua Braithwaite because it wouldn’t have been very good for morale to report that someone of his standing hadn’t the spunk to face up to losing his son.’

‘Are you saying he was trying to drown himself? That it was an attempted suicide?’

‘Same reporter, rest his soul, Harold Buckley. Used to complain that if a story wasn’t spiked it was in danger of being “smoothed out” by the editor. Bit of an old die-hard radical, anything political, anything to challenge the bosses and Harold was there. He covered the founding of the Independent Labour Party, that’s how far back he went. It was just up his street to spill the beans on a Bradford millionaire, a bloated capitalist.’

‘How was his story “smoothed out” as you put it?’ I asked, as Mr. Duffield escorted me back to the lift.

He looked round quickly to ensure we were not overheard. ‘Apparently, and this was according to old Harold, our millionaire mill owner wanted to be left to die. There was talk of a prosecution for attempted suicide. Then Braithwaite disappeared into thin air. The man must have had enemies or Harold wouldn’t have heard about him.’

The lift clanked me down to the ground floor. Why hadn’t Tabitha mentioned the beck, the boy scouts and the stories of suicide? She must be saving that treat.

I cycled home from the newspaper library, leaving the smog of the city behind. April sunshine streamed through the trees on Woodhouse Moor, creating a pattern of branching shadows. I wondered who, back in August 1916, had gone to the newspapers with the Braithwaite story.

A familiar car sat outside my gate—one of the sleek black Alvis saloons favoured by West Riding Constabulary HQ. It could mean only one thing. Dad had decided to pay me a visit. Either he had psychic powers, which would not in the least surprise me, or Mother had telephoned and winkled my fledgling plans from Mrs. Sugden.

I wheeled my bike into the garden with a sudden dread that something might be wrong. Dad didn’t usually visit me during the day, not when on duty.

‘Dad!’ I called as I opened the front door.

He emerged from my tiny drawing room, lowering his head so as not to bump it on the door frame. He smiled. ‘Hello, love.’ He was wearing his smart superintendent’s uniform with gleaming buttons. His easy manner quelled my anxieties. ‘My sergeant’s in the kitchen, having a cup of tea with Mrs. Sugden. We’ve been at the Town Hall for a meeting. Just did a bit of a detour to speak to a chap at the cricket ground regarding an inter-force match.’

As a young chap, Dad played rugby and cricket and still picked up a bat now and again.

We looked at each other. He raised an eyebrow in answer to my unspoken question. The cricket ground detour had provided his excuse to call and see me. I knew that Mother had spoken to Mrs. Sugden, and then managed to get word to Dad.

‘How’s Mother?’ I tried to keep the suspicion from my voice.

‘She’s very well. Would be even better if you’d agree to go shopping with her on Monday, but I understand you may have other plans.’

The annoyance started somewhere around my toes and eased its way up. Mrs. Sugden may be the soul of discretion, but not where my mother is concerned.

‘Dad! I’m a big girl now.’

‘I know, I know, love. And I suppose I’m to blame for the sleuthing.’

‘Yes. I suppose you are.’

‘Inherited, eh?’ He winked at me.

I laughed. ‘Almost certainly.’

The truth is, I am adopted and so any aptitude I have for investigation is not an inheritance of the blood. Perhaps it arose from a fascination with polishing Dad’s silver buttons, or having a failed police bloodhound as a pet.

I was adopted as a baby, when Mother thought she would not have children. When I was almost seven, she had my twin brothers. By then I must have passed the trial period because I was not returned to sender as surplus to requirements.

I call the little wood at the back of my house Batswing Wood because a glossy dark green ivy grows there whose leaf forms the shape of a bat’s wing. There are maples, sycamores, elms, beech trees, a bracken fern and toadstools. A pregnant-looking oak, massive growth protruding from the middle of its trunk, takes centrestage in a flat raised area of the wood where local children sometimes perform their magical plays on summer afternoons.

In a clearing, Dad and I sat on a bench hewn from a fallen beech tree by some long-ago gardener. I told him about Tabitha’s letter and my visit to the newspaper library.

Dad entered into the spirit of the case straight away. ‘How have Mrs. and Miss Braithwaite coped in the past six years? Until it’s established to a court’s satisfaction that a man has died, the financial assets are frozen. And who’s been running the mill?’

‘I don’t know.’

He stretched his legs. The bench is too low for a tall man. ‘Sounds as if there could be a lot of practical difficulties. I’m surprised the widow hasn’t applied for presumption of death before now.’

‘From Tabitha’s letter she’s obviously hoping he’ll be found alive. Missing doesn’t mean dead.’

I had said the wrong thing. Dad went quiet. I knew what he was thinking. Why doesn’t Kate accept that Gerald won’t be coming back? Missing only means: No one saw him die and lived to tell the tale. Presumed dead means blown to smithereens.

‘I expect I’ll find out more when I speak to her,’ I added quickly. ‘From her letter, I don’t think it’s about money.’

He shook his head. ‘People never do say what it’s really about. The court will expect to hear that all attempts to locate Braithwaite have been exhausted.’ He watched a squirrel run up the oak tree and dart across the branches, heading towards the big house. ‘From what you say, Kate, this won’t be like the cases you’ve taken on before, not like finding information for some bereaved soldier’s relative. You’ll be stepping into a different sphere. Bradford-Worstedopolis, wool capital of the world. Hard brass at stake.’

‘It’s different in another way too, Dad. Tabitha must think I do this work professionally. She’s offered to pay me, and I’m inclined to say yes.’

To my surprise he gave me a broad smile. ‘Couldn’t be better. Fits perfectly. After all in the last couple of years you’ve probably tracked down more recalcitrant husbands and sons than a small police force.’

He swayed slightly, with that gleeful involuntary movement that means he expects he is about to get his own way. My suspicions were roused.

‘What do you mean “Fits perfectly”? What fits?’

‘I have a suggestion to make. There’s a chap lives not a mile from here, in Woodhouse. He’s ex-force, face didn’t fit, so he left. Since then he took on short-term security work for a shoe company who had rather too many boots walking away. Now that’s at an end, I’d like you to meet him.’

I turned to him, protesting. ‘Dad! I can’t promise a man permanent employment.’

‘Take him on for this case. See how you get on. Don’t forget you’ll be off to London for Berta’s party. And we’re there over Easter. You’re not going to let your mother down over that are you?’

‘No.’

He was winning me round to the idea. But I still felt a tug of reluctance. Yes, it could be useful to have someone to help. After all, Sherlock Holmes had Dr. Watson. On the other hand, I’m my own woman. An ex-policeman sounded a daunting prospect. Bound to be a know-it-all.

Dad made a steeple of his fingers. ‘Your mother worries. She tracked me down to the Town Hall and bent my ear this morning. If I can tell her you have a chap utterly fearless, straight down the line who’ll . . .’

‘I don’t need protection.’

‘. . . who’ll be your assistant and take on some aspects of the work. If you do that, then I think I can persuade your mother to leave you alone to . . . to get on with your life.’

There was a gulp in his voice. He wanted me back as much as she did. They don’t see that if you’re thirty-one years old, it’s too late to be a little girl again. I was in the big bad wide world and had to do something, or I would go mad.

‘Need to stretch my legs.’ Dad stood up. I took his arm as we walked along the path to circle our way round Batswing Wood. ‘I know how you feel about wanting to make your own way in the world, Kate, but there are limits, even for someone as independent as you. You’ve searched out military men before—with a lot of goodwill from their comrades and officers. This will be a different world. From what you say about the missing Mr. Braithwaite, it’ll be useful to ask a few questions in the Bradford Wool Exchange. You won’t hear the swish of a skirt there, unless it’s an early morning cleaner.’

‘Hang on a minute . . .’

‘You need someone who’ll do a bit of leg work.’

A branch of mistletoe caught my skirt. I stopped to untangle myself. ‘I like to see who I’m talking to, Dad, weigh them up, try and understand what they’re not saying.’

‘You need to know what your own strengths are and not be afraid to accept help. If this young woman is due to be married in how long . . .?’

‘In just over a month’s time, on the first Saturday of May.’

He let out a soft whistle and shook his head. ‘Even I would think twice about taking on that kind of job. You’ll be hard pressed to get any kind of conclusion without help.’

We had circled the wood and reached my back fence. Through the kitchen window I could see Dad’s driver, leaning across the table, lighting Mrs.. Sugden’s cigarette.

I thought over Dad’s words. Perhaps it wouldn’t hurt to have help, just this once, given the urgency of Tabitha’s request. ‘What’s the name of this ex-policeman, security man, pursuer of missing boots?’

‘Sykes.’

‘As in Bill Sikes? Notorious villain, slayer of Nancy?’

‘Not Bill, Jim. Jim Sykes. He’s 35 years old, a married man with three children. You’ll need to pay him at least two pounds a week, so cost that into whatever you charge for the job.’

‘I haven’t said yes. Either to the job or Sykes.’

‘Meet him. See how you hit it off.’

I did not want Mr. Sykes to come to the house, or for me to go to his, in case we did not get on and I had to decline his services. We were to meet on Woodhouse Moor, a little after six that evening. I would rendezvous with Sykes on the second bench, as arranged through Dad.

I wore my belted dress with matching cape, and Cuban heels with the strap. This seemed to me a businesslike look. The damp evening air felt fresh and sweet. A light rain started as I reached the moor. I unfurled my umbrella. Suddenly, the situation struck me as comic and absurd. A little voice in my head mocked the whole business and said that I should be wearing a red rose between my teeth, to fling at him and say, ‘You are Jim Sykes, son of Bill the slayer of Nancy. I claim my prize.’

Since telephoning Tabitha and arranging to meet her on Monday, I had tried to recall all I knew about mills, worsteds and woollens. From my thimbleful of knowledge, I remembered that Harris tweed, Irish tweed, Scottish tweed and for all I know Yorkshire tweed are sometimes lumped together under the name “homespun”. Then I spotted him.

It seemed appropriate that here was a man, sitting in the centre of a bench, wearing a homespun suit, a pulled-down trilby and highly polished brown boots. Perhaps the brown boots were his bonus from the shoe company for whom he had acted as security man. They looked new.

He tilted his head towards the sky as if asking the drizzle how long it might last. His umbrella remained furled. At first glance, he appeared totally unconcerned with all around him. At second glance, I saw that he missed nothing. Likely he had a pinhole in the back of his trilby for the convenience of the eye in the back of his head.

Wiry and wary, he sat bang in the centre of the park bench, as if daring any other person to claim a seat.

Although he had not appeared to notice my approach, he leaped to his feet and raised his hat in a pleasant manner.

We shook hands and he moved along the bench, making room for me, on the dry spot where he had previously perched. Fortunately the brief spit of rain stopped so we did not need to negotiate umbrellas.

A good four inches shorter than Dad’s six foot, Sykes was six inches taller than me, with the kind of pronounced cheek bones, ears and nose that make me think of the skull beneath the skin, and of poor Yorick. That leads me on to imagine that here’s a man who will look at himself in the mirror while shaving and know that he must make the most of his short time on earth. Not very logical, but I can’t always help the trains my thought catches. He was clean shaven, though I had for some reason expected a handlebar moustache. He had bright intelligent eyes, with the sort of bags under them that I associate with mothers whose children keep them awake in the night.

Dad had told me that Sykes’ face didn’t fit. That his boss got the wrong man for a robbery and told Sykes to let it go, but Sykes wouldn’t. ‘That’s being a good copper in my book,’ Dad had said. But in Sykes’ nick it was seen as insubordination. He would never rise above pounding the beat, and with the worst shifts his sergeant could throw at him. When I asked Dad could he not have intervened, he said that it did not work like that. Sykes resigned.

For a few moments we exchanged words about how long Mr. Sykes and his family had lived in Woodhouse, which was five years, and how long I had lived in Headingley, which was eight—since Gerald and I married in 1913 after our whirlwind romance. Of course if I took off my time away in the VAD, I had hardly lived in my little house at all until the end of the war.

Behind us some lads began to kick a ball about. A woman wrapped tightly in a musquash fur coat walked along the path, talking kindly to two Pomeranians who trotted alongside her.

‘How well do you know Bridgestead and the mill business, Mr. Sykes?’

He turned to me with a solemn glance, as formally as if I were an entire board of directors interviewing him for the post of bank manager. ‘I don’t know Bridgestead at all, madam. But I have family who work in the mills.’ He told me about his aunts who worked in Listers Mill, and of the spinners and weavers who were his ancestors. ‘My knowledge should help me to blend in and not arouse too much suspicion while making enquiries.’

‘Where would you begin? My father mentioned the Wool Exchange.’

‘That would be on the list certainly, Mrs. Shackleton, especially on the meeting days, Monday and Thursday. But I might begin by finding out which public house Braithwaites’ workforce frequent. There’s gossip to be picked up over a pint and some of it proves useful.’ He paused, giving me a chance to question him.

‘I shall visit the Bridgestead village bobby, Mr. Sykes. Is there anyone you could draw on for information?’

He looked thoughtful. ‘There’s one or two officers in Keighley who’d be willing to talk to me about what they remember of Joshua Braithwaite. If you agree, I’d like to find out what I can without revealing my connection to you.’

‘Why would that be, Mr. Sykes?’

‘Call it a copper’s instinct to play his cards close to the chest. But I believe there are two kinds of people in the world—them that cough out information and them that gather it up.’

He made the work sound as though we would be walking about offering a spittoon to passers-by.

‘And how would you keep your connection to me secret, and yet find out all you wanted to know?’

‘I’d have some good story—as I expect you may have.’

I had not thought of that. ‘Until I see Miss Braithwaite, I’m not sure how I’ll proceed.’

I told him what I had read in the newspaper library and about the librarian’s story from the reporter on the scene that Mr. Braithwaite had tried to commit suicide.

Sykes shook his head sadly. ‘Attempted suicide’s a nasty business. And it muddies the beck, if you’ll pardon a pun.’ Sykes let out a sigh. ‘The Keighley lads will tell me whether they had the bloodhounds out searching for a body.’

Without our having formally agreed to a working arrangement, I realised with surprise that we were already jointly on the case and were discussing who would do what.

I would speak to the family and the village constable, and try to find out whether there had been family or financial difficulties. Sykes would quiz the workers, Keighley CID and connections at the Wool Exchange.

‘My father says two pounds a week would be an appropriate remuneration,’ I said, thinking it best to get this out of the way.

‘He said that to me too. And there’d be any expenses I might incur, travelling, standing a drink, and so on.’

‘So perhaps you would like something on account?’ I took a folded five pound note from my pocket and handed it to him.

He grinned for the first time. The smile lit his face and I saw the relief. He would go home to his wife and children and say that he had a job.

He extended his hand and this time the handshake was stronger and held longer. ‘Thank you. You won’t be sorry.’

‘I’m going to Bridgestead on Monday. I suggest we meet, say Tuesday evening and compare notes.’

He nodded. ‘I’ll take the train to Bingley, that’s nearest.’ He took out a notebook and wrote the name and telephone number of a hostelry. ‘I know the landlord at the Ramshead Arms. He owes me a favour and will give me a room if necessary.’

‘Six o’clock. And if I can’t make that time for any reason I will telephone Mrs.. Sugden and she’ll send word to you.’

And that was how I came to work professionally for the first time, and to employ Jim Sykes, the man in the homespun suit.

Chapter 3

The Silesian Merino Shawl

Early on Monday morning, the sun shone brightly in a crisp blue sky. It was the kind of day when you look through the window and expect that it will be warm, only to get a chilly surprise when you put your nose outdoors. I loaded the boot of my Jowett convertible with portmanteau, camera bag and walking-stick tripod. I had packed my Thornton-Pickard Reflex, useful with or without a stand. The tiny Vest Pocket Autographic Kodak slid into the notebook section of my satchel. The VPK is to other cameras what a watch is to a clock, as the slogan goes. In other words, easy to lose at the bottom of your handbag. Mrs. Sugden shook the travelling rug and folded it carefully.

Setting off can be a trial.

Mrs. Sugden will say, ‘Have you got the map?’

‘Yes.’

Two minutes later: ‘Have you got your driving goggles?’

‘Yes.’

A minute later: ‘Is there petrol in that there can?’

At which point I pretend not to hear, and have totally forgotten what it was I meant to remember.

In spite of the sunshine, it would be a chilly ride. My motoring coat is a great fleecy swaddler with detachable lining. It saw me through the war and is way out of fashion, but it makes me feel safe, secure and immune to traffic accidents.

I pulled on my tasselled motoring hat and gauntlets.

‘Have you got . . .’ Mrs.. Sugden began.

I turned on the petrol tap.

‘If I haven’t got, it doesn’t matter.’ I switched on the ignition. ‘I’m going to Bingley, not the North Pole.’

I turned the choke to rich and pressed the starter button. You will gather from this that my motor is modified for easy use, and I don’t apologise for that so there.

Mrs.. Sugden waved. ‘Go careful!’

‘I will.’

Rain during the night had dampened the roads so they were not so very dusty. Once out of Leeds, I made good progress, through villages, past farms and mills, keeping an eye on the signposts and milestones.

I thought about the time Tabitha and I last met. It was almost two years ago, June, 1920, at the opening of the Cavendish Club. All through the war, we VAD girls had nowhere in the capital to call our own. Afterwards, that was put right and Tabitha and I were among the supporters of the campaign for a club that women could afford. Since then, the two of us had promised in our Christmas letters and summer postcards to meet up, never doing so until now.

We had arranged to meet in a café on Bingley High Street. Once parked by the side of the road, I shed my antique coat, swapped the tasselled hat for a cloche, and set off to find the café.

Looking over the red and white check curtain that hung across the lower half of the plate glass window, I saw her. With one hand she held a cigarette, with the other she twirled at a strand of her blonde curly hair. She has the quality of a Dresden doll, with neat features, a snub nose and bow lips.

The bell rang as I opened the door. The waitress, taking away Tabitha’s full ashtray and placing a clean one on the table, blocked me from view. Then Tabitha was pushing back her chair, and coming towards me. I was about to hold out my hand when she gave a beaming smile, grabbed me and pulled us into a clinch. We kissed each other on the cheek.

‘Kate, thank you so much for coming! I’ll order another pot of tea.’

After the preliminaries about my journey and whether I found my way easily, she said, ‘You’re so kind to come at such short notice. I hope you don’t mind my turning to you for help. You were always so capable. Do you remember I couldn’t think straight when that poor chap in St Mary’s died under my care?’

I nodded. ‘You’d become attached to him.’

She sighed. Her fingers played a silent requiem on the tablecloth. She looked much younger than her thirty years, almost like a schoolgirl.

‘You get to the bottom of things, Kate. You tracked down the brother of that Cavendish waitress.’

‘Even though he wished I hadn’t.’ I smiled. ‘But I think people have a right to know the truth – no matter how hard it is.’

You can never tell whether someone will immediately blurt out every single detail of their story, or sidle up to the matter in hand so slowly as to trip over it. Tabitha is a sidler-up and tripper.

Finally, she said, ‘I look for Dad all the time. Just before I came in here, an old chap went shuffling by the ironmonger’s and I thought, is that him? It wasn’t. It never is. But I don’t stop looking you see. Sometimes, if there’s a knock on the door, I think it’s him.’

‘Would he knock on his own door?’

She lit another cigarette. ‘No. But none of it has to make sense. I even dreamed he came back, walking through the fields from the mill, with some other men, saying he’d not been lost at all and we’d only thought him lost. Mind you, it’ll be Easter a week on Sunday. Resurrections and all that.’

‘So you think he’s lost, and not dead?’

‘He’s not dead. I’m sure of that.’

‘How can you be so sure?’

‘I just am. I know in my heart and soul. You know when someone is dead.’

There was logic to that. But just because you knew when a person was dead, that did not mean you could be certain that someone was alive. There seemed to me to be a shade of difference between her declaring him ‘not dead’ and asserting that he was alive. Perhaps he was not dead because she could not bear that.

When someone has gone missing, there is always that edginess, that looking out of the corner of the eye. Even when your head knows that he will never come back, that part of you that hopes beyond all reason just won’t give up. When trying to find out what happened to Gerald, I had spoken to his colonel, pushing him for names, survivors who might have some scrap of information for me. He grew impatient. In the end, he said, ‘My dear madam, please understand that the words “Missing in Action” frequently mean “blown to smithereens. Nothing left to identify”.’

If she saw the shadow cross my eyes, Tabitha thought it was for her.

‘It’s come between me and Hector, my fiancé,’ she confided in a low voice as if the waitress would be listening, ready to spread gossip, which perhaps she would to make up for having to watch everyone else eat egg custards. ‘He practically holds his breath and turns purple if he suspects I’m going to harp on about Dad again. At first he was patient but now . . .’ She blew a perfect smoke ring. ‘If you can’t find an answer for me, Kate, I’ve got a horrible feeling this wedding will never happen.’

‘Tabitha. I can stay with you until Saturday. The following week I must go to London for my aunt’s birthday dinner. It would be more than my life’s worth to back out. Then we have the Easter weekend. Let’s see whether I can be of any help. Perhaps by this Friday we shall have a better idea.’

We left the café and strolled around the market town. I told Tabitha I wanted to stretch my legs, which was true. But I also kept an eye open for the Ramshead Arms where I would meet Sykes on Tuesday evening. I suddenly felt absurdly competitive with him. I wanted to find out as much as I could – just to prove that it wasn’t necessary to swagger around male preserves like the Wool Exchange and the local pubs to get to the bottom of a mystery.

Women with shopping baskets hurried by. A furniture van unloaded a desk outside the solicitor’s office. Tabitha steered me on a compulsory visit to the stone church with its fine tower where she and Hector would marry.

‘There’s a lovely set of bells. I do hope you’ll come to the wedding, Kate. I posted a formal invitation this morning. Sorry it’s a bit late.’

She seemed reluctant to walk back to the car. We stood on the packhorse bridge and listened to the water. ‘What arrangement do we come to, Kate? About fees and so on?’

I should have sought advice on this, but I hadn’t. Mental arithmetic is not my strongest point, but if I were to pay Sykes’ wages and expenses, for at least a month, that had to be taken into account.

I played for time. ‘You can pay me on completion. I shall give you a report – verbal or written, as you please, whether I’m successful or not, and send an invoice.’ This waffle allowed me to put off saying an amount. ‘It’s difficult to be precise about costs without knowing how much investigation may be involved but . . .’ I pulled a figure from the air and said it quickly so that it would not sound made up. ‘. . . let’s say thirty guineas.’

She sighed and turned her back to the wooden parapet. ‘It would be worth three hundred guineas to me, three thousand – no, it would be worth all I have to see my dad again.’

The enormity of the task made my knees go weak. Perhaps there had been dust on the road after all. My mouth and throat felt suddenly dry.

‘Tabitha, some people would have applied for presumption of death long ago, to enable a life insurance claim to be made, and access to bank accounts and assets. How have you and your mother managed all these years?’

She took my arm as we walked back past the church and along the main street to the car. ‘We are all on the board of Braithwaites Mill, Mother, Uncle Neville and me. Any two of us can deal with the finances, sign cheques and so on. The company provides our living. Mother and I have our own financial resources. I would give up everything to find Dad.’ She pressed my arm tightly, like a plea.

‘I can’t make any promises, Tabitha. I’ll try, that’s all.’ I folded down the car’s top and opened the door.

Tabitha has a mercurial quality of switching moods in an instant. She pulled off her hat as she slid onto the passenger seat. ‘There’s nothing like the wind in your hair to make you feel free as a bird.’

As I chugged the car forwards, an old lady made a dash for the other side of the road, pretending not to see me. Perhaps she was after compensation. If I ran her down, no doubt I could add it to Tabitha’s bill, along with my legal defence fees.

Tabitha ignored our near miss. ‘Drive straight along, past the corn merchant’s. It’ll be a right turn by the Cooperative Store.’

We left the town behind. I felt alarmingly satisfied so far, having found out a little from Tabitha about the Braithwaites’ financial background, and, just as importantly, having located the Ramshead Arms where I would rendezvous with Sykes.

Hawthorn bushes edged a country lane. Daffodils still held tall. This was far from the dark satanic mills I had pictured.

As the road made a bend, I caught a glimpse of horse-drawn barges on the canal.

She was twisting her hair again, making a ringlet around her index finger. ‘We’ve a way to go yet. The road runs between the canal and woods. No one ever comes to Bridgestead. We’re a bit remote from modern life really. Seems strange, after all of you-know-what.’

I did know what. The what that came to seem ‘normal’ during our time as VADs had probably sent us slightly mad.

She punched my arm, a little too hard. ‘Do you remember the time when there were too many of us trying to get a billet in London for just one night . . .?’

‘Yes. And we ended up piling into my aunt’s house and Betty Turnbull sneaked down in the night and made a midnight feast of our breakfast.’

‘Betty Turnbull! Then she came back upstairs and snored fit to shake the roof . . .’

We started to laugh. A rabbit dashed from the hedge and dared me to run it down. Another second and I would have had the makings of a fur muff but I swerved, barely avoiding the ditch.

I restarted the car and chugged along sedately, enjoying the fresh air until we passed a farm where the workers were busy muck-spreading.

‘It makes such a difference when the sun shines! You live in a lovely area, Tabitha. I’d imagined it much more cobbles, chimneys and clogs.’

‘Oh we do that too. But we’ve some pretty spots nearby. Do you ride?’

‘Rarely. It wouldn’t be fair of me to keep a horse.’

‘We all ride. Mother’s a keen horsewoman.’

Something in her voice hinted at a possible obstacle to our investigations.

‘Does your mother know I’m coming to stay, Tabitha?’

‘Y-e-s. Only, to be truthful, she doesn’t know why. I thought once she got to know you, I’d sort of raise the matter of finding Father in a day or so, when I mention what you do.’

‘I can’t work like that, Tabitha. I must have straight dealings. And if I’m to investigate properly, I’d need to talk to people. Naturally I’ll be discreet.’

She reached out and touched the windscreen with her fingertips as if to deflect a shock. Her voice rose. ‘Other people?’

‘Yes. The local constable, and whoever else was involved. I’ll need a list.’

The tips of her gloved fingers left tiny imprints on the now dusty windscreen. Her arms fell helplessly to her sides. ‘I suppose so. I hadn’t thought of that.’

It struck me that she hadn’t thought of very much.

‘Time is of the essence. If you really want me to try and help, I must start straight away. I’ll need you to give me a photograph and a description of what your father was wearing, where he was last seen and by whom. What was his state of mind when he went missing, whether he had transport, what his possible destinations may have been. The more you can tell me about his interests, friends, acquaintances, business associates, the better.’

‘Yes I suppose so,’ she said flatly. ‘Mother won’t like it. Uncle Neville won’t like it. We can’t involve the business. He’d hate that. You don’t know what mill people are like, Kate. They play everything so close to the chest, never wash dirty woollies in public.’

I thought perhaps I did have a notion of what they may be like given that it had taken Tabitha this long to confide in me and that she seemed daunted by the thought of how much information I would need.

‘Look, you don’t have to go on with this. I’ll come in, say hello to your mother, we can talk over old times and I’ll drive home in the morning.’

She sighed deeply. ‘Can I talk now? Can you listen and drive?’

‘Yes.’

‘That little lane over there takes us on a byway and off the beaten track so that we come to Bridgestead the long way round. You drive. I’ll talk.’

I was not entirely sure my supply of petrol would run to a detour. I pulled in by a five-barred gate. In the field beyond, a horse and foal grazed, the foal looking up at us.

‘I’m listening.’

She fidgeted with her engagement ring. For a moment, it distracted both of us. I stared at a sizeable rose-cut diamond flanked by rows of glowing single-cut diamonds and with shoulder-mounted square-cut rubies, glinting in the afternoon sunlight. ‘I have to try to find Father before the wedding. It’s the right thing to do, whatever anyone else says.’

‘What does everyone else say?’

‘That everything was done at the time. The police searched. Mother offered a reward for information. She assured me that everything would be done to find him. I wasn’t able to do much, going wherever the VAD sent me. Oddly enough, it was on the day we met that he went missing. Do you remember? On that ward full of poor men with shell shock.’

We were silent for a few moments. The foal lost interest in us and tottered after its mare. In the far corner of the field, a crow swooped.

‘I read a newspaper account. It said that your father was found by boy scouts, and saved from drowning. Do you believe there was any reason why he may have wanted to take his own life?’

She shuddered. ‘That’s not it. That’s not it at all. He didn’t try to take his life.’

‘How can you be sure?’

‘I just know it.’

‘We have to look at every possibility. I believe your brother was killed just weeks before your father was found by the beck.’

‘Yes.’ She clasped her hands, twirling her thumbs.

It felt cruel, making her talk about her brother.

‘Poor Edmund. There were just the two of us. Edmund volunteered, but then everyone did, didn’t they?’

‘What happened?’

‘He was killed on the first day of the Battle of the Somme. But Dad was stoical, as we all were. He wouldn’t have attempted to take his life. He wasn’t a despairing kind of man.’

‘Can you tell me about the last time you saw him?’

For a moment, she looked as if she would cry. ‘I’m afraid my mind’s gone a bit of a blank.’

‘Try.’

A blackbird trilled in the hedge, as if nothing in the world could ever be out of kilter.

‘It would have been a Sunday dinner, sometime that month. August. There were just the two of us. Mother claimed a headache. Truth to tell she could hardly bear to be in the same room with Dad, not since Edmund was killed.’

‘Why was that do you think?’

She shrugged and shook her head. ‘I don’t know all the ins and outs. She thought Edmund shouldn’t have joined up, at least not so soon, and that he only did it to get away from Dad, and from having to stay in the mill. We were busy producing khaki, so Edmund could have avoided the army.’

For the moment she seemed to have run out of words.

I restarted the car.

Following Tabitha’s directions I drove up a steep cobbled street of densely packed two-storey cottages, past a school with high windows.

‘If you look over to your left, you can see the mill chimney. We’ll continue up the main street. You’ll soon find your bearings.’

The row of houses gave way to a solid stone building with sturdy pillars and portico. ‘That’s the Mechanics’ Institute. The lecturer comes from Keighley. Just up ahead you’ll see the chapel. Dad was on the committee. Uncle Neville takes an active interest.’

‘Is your family very religious?’

‘Not in an out of the ordinary way. Mother and I are Church of England thank goodness. Gives you a much better class wedding. A chapel do would be so ordinary and plain. But all mill masters have to make a show in some chapel direction, and encourage their hands. It’s what keeps the mills in motion, Dad always says.’

‘Is Uncle Neville your mother’s or your father’s brother?’

‘Dad’s cousin, so I suppose not a fully-fledged uncle, but the nearest we’ve got. Head towards the mill and keep going.’

I caught sight of a humpback bridge and heard the sound of running water. ‘Is that the beck?’

‘Yes. Dad was found by the stepping stones, where we used to play.’

We stopped to take a look.

Standing on the solid old sandstone bridge, we watched water play over rocks, murmuring and rushing as if to keep an important appointment.

‘He was a smashing dad, Kate. I love him. I want him back. See just there, by the stones, that’s where Edmund and I used to play, trying to make a dam, fishing, that sort of thing. Dad painted a picture of us once.’

‘So he didn’t entirely lock himself away in his work, if he found time to paint?’

‘Mills can be monsters – eating up lives – but he did sometimes paint.’

In as neutral a tone as possible so as not to seem critical, I asked Tabitha why she had left it so long before deciding to search for her father.

‘Mother said everything that could be done at the time was done. But you see, I didn’t do anything, being off in the VAD. And I must do something, otherwise it’ll haunt me forever that I didn’t try.’

‘Have you made any enquiries?’

‘People are so close-mouthed, or they say what they think I want to hear. I’m hoping you’ll be better at getting the truth than I’ve been. Someone must know what happened to him.’ She turned to me. ‘Here I am rabbiting on and I haven’t even asked how you are yourself. You had a telegram too, just as we had for Edmund.’

‘Not quite the same.’ I kept my voice steady, feeling foolish to let hope betray me. ‘Mine was a missing telegram. I tried to find someone who saw Gerald on that last day. The nearest I got was a sighting in the late morning, before the big bombardment, a sighting of Gerald walking along a road.’

I didn’t say all those mad things about waking in the night and imagining that he walked to safety; that he lost his memory; that he works as a peasant in a remote spot, not knowing who he is and that one day . . .

The Braithwaites’ elegant stone villa was of an unusual design. The centre comprised four storeys. Adjoining either side were extensions of two storeys, giving an impression for all the world like a person resting on her elbows. Shutters, the same dark green as the front door, framed latticed windows.

‘Grandma had it built around 1900,’ Tabitha said. ‘It was terribly modern at the time.’

To the right and left of the house stood outbuildings, stables and garages. Neatly planted flowerbeds and a bare-looking rose garden flanked the drive. A fountain in the Italian style played in the centre of the beds.

‘We’ve a tennis court round the back, if you’re brave enough to bear the April breezes.’

‘Where shall I park?’

‘Oh just any old where. Briggs will see to your car.’

I brought the car to a stop and stepped out. Tabitha followed, pausing on the running board.

‘I wasn’t entirely truthful when I told you Mother knew you were coming.’

‘I’m not expected?’

‘I didn’t know if you’d come.’

‘But I said I would.’

‘I know. I’m so . . . I’m such a big baby about some things. I can’t explain it.’

‘Do you think she won’t want me here?’

‘It’s not her. It’s me. I thought you might change your mind, or have an accident, or find something better to do and then I’d look a fool and she’d say, “Oh that’s Tabitha all over, makes a plan and nothing happens.”’

‘I wouldn’t just not turn up.’

Tabitha suddenly looked like what my mother would call a bag of nerves.

‘I know, I know. I want my head examining. I always expect something terrible to happen. I so much wanted you to come, but was afraid to count my chickens. This is going to sound mad, and like wedding nerves, but I don’t believe anything good will ever happen if I don’t find Dad. My life will just unravel.’

I’d seen this sort of response before. In 1919 I was maid of honour for a girl I was at school with, and it was touch and go in the end. She and her childhood sweetheart had come through the most terrible times with great strength. Then, when life promised happiness – a wedding for heaven’s sake – she went to pieces, saying that she knew for certain that nothing in life would ever go right again and to pretend otherwise was tempting fate.

I touched Tabitha’s arm lightly. ‘Better tell your mother about me.’

‘At least your room is ready. Becky knows you’re coming. She’s very reliable and will look after you. Leave your bags.’

I picked up my canvas bag. ‘I’ll keep this with me. It’s my photographic equipment.’

‘Right.’ She hesitated at the steps of the house, turning to me. ‘Thank you for coming. I’m sorry I’m such a drip. Hector knows you’re coming, but not why. Whatever you do, don’t mention to him that you’re investigating Dad’s disappearance. He’s so sensitive. Perhaps he thinks Dad might turn up and put the brakes on the marriage.’

‘Why would he do that?’

She blushed. ‘Because Hector’s ten years my junior, and everyone expects that he’ll find some useful occupation on the board of the mill. Well, why shouldn’t he?’

Was this her way of telling me that Hector was marrying her for money? If that ring was anything to go by, he was no pauper. ‘It’s a family business and your husband will be family . . . That’s how it works, isn’t it?’

Privately I wondered whether Hector knew something about Joshua Braithwaite’s disappearance that Tabitha didn’t.

A soft wool shawl in rich shades of purple and mauve lay folded on the cushioned window seat. The walnut bureau held an inkstand, pen and paper. A vase of daffodils stood on an occasional table. Someone had thought of everything.

The latticed window looked on to open moorland. The sun had moved almost out of view, causing the dry-stone wall to cast a long shadow onto the rockery.

The floor of the dressing room provided a suitable place for my cameras and equipment. Bringing my photographic stuff served a dual purpose. After talking to Sykes, I realised that an investigator needs cunning and reserve. If I drew attention to myself around Bridgestead, it would be as an amateur photographer and thus I would allay suspicions. That was my theory at any rate.

In truth my desire not to be parted from my cameras may have been more to do with attachment to my gentle hobby. It is a pastime that changes a person’s outlook. I remembered my excursion to Whitby when I first made really good use of the camera. A school friend was recovering from a bout of fever and the doctor ordered sea air. All these years on, I can remember quite clearly the fishing vessels bobbing on the bay, the austere outline of ruined Whitby Abbey, casting its shadow at dusk, the limping pie and peas seller pushing his cart. Even when my photographs did not do justice to the scene, which was most of the time, simply framing the views developed a photographing habit that changed my way of seeing. A photographer’s eye sharpens memory from a vague or hazy recollection to a clear image of an everlasting moment. Owning a camera gave me a new interest in people and landscapes, in markets and busy streets. It is a way of looking outside yourself and at the same time gathering up mental albums of memories.

It was in Whitby I met Gerald. He and a friend were there for a weekend fishing trip, staying in the same hotel as my friend and I. He gave up one of his fishing trips to introduce me to Frank Meadows Sutcliffe, that wonderful photographer of local people and scenes. After seeing his work it was a toss-up whether I would throw away my camera or reach for perfection. He set me on the path of photographing people going about their business, getting on with their work and lives, pausing for the camera, and for eternity, or for as long as photographic chemicals will allow eternity to last.

Mr. Sutcliffe took our photograph and when Gerald and I left his studio, even though we had known each other for only hours, something was settled between us without the need for words.

As I closed the closet door on my photographic equipment, there was a knock on the door. Becky the maid scooted in a young houseboy who deposited my portmanteau. At the same time, I heard horse hooves on the flagged courtyard below.

Tabitha had said her mother was out riding. I went to the window in time to see Mrs. Braithwaite sitting upright on her horse, its head tossed slightly to one side.

She dismounted quickly and gracefully. Before her riding boots touched the flags, a groom appeared to take charge of the chestnut bay mare. She patted the horse’s neck and spoke briefly to the groom before turning towards the house. Her dark bobbed hair gleamed in the late afternoon sunlight. She seemed to glide up the steps to the house in such a slow deliberate way that I expected her to leave an impression on the air after she sailed through it.

Slowly, I changed from my motoring outfit into an afternoon dress. It occurred to me that Mrs. Braithwaite looked like the kind of woman who could browbeat the entire West Riding police force and hire a small army of private detectives. The task ahead seemed suddenly more daunting. If no one else had traced Joshua Braithwaite, what on earth made me think I would?

Tabitha tapped on the door. ‘Are you ready to come and meet Mother? It won’t take her long to change out of her riding togs. I’ve told her you’re here.’

Tabitha now wore an exotic Chinese silk smoking suit decorated with bridges, nightingales and bashful lovers. A long ivory cigarette holder peeped from the top pocket.

I sat down on the window seat. ‘Just one more thing, Tabitha. You and your mother know everyone. All the questions I’m going to ask, she probably already has. From my brief glimpse of the way your mother dismounts, I’d say she’s a very capable woman.’

Tabitha joined me on the window seat. ‘You can’t tell a person’s character from the way she rides a horse.’

‘Perhaps not.’ I said.

Tabitha picked up the shawl. She shook it out – a swirling intricate pattern in the most exquisite shading, from lightest violet to darkest purple, with a delicate fringe.

‘This is Silesian Merino, it’s the finest wool in the world. The bulk of German sheep are merino crossed with native breeds, but the Silesian is highly prized. This shawl was a gift from Mr. von Hofmann, a chemist who had his own dyeing company. Before the war, he and his family were our regular visitors. We used to go to concerts together. There’s an area in Bradford, off Leeds Road, called Little Germany. That’s where Germans had their warehouses and offices.’ She folded the shawl carefully. ‘Some people said Dad was too close to the German merchants, and especially too close to Mr. von Hofmann. But they were friends. That’s all. When they all had to leave, go back to Germany, there was cruel talk. People said we were German sympathisers. Uncle Neville wasn’t included in the lies, but Dad was. I think all that talk, all those feelings might have got in the way of finding out the truth when Dad went missing. People were so fierce at that time. One old lady in Bingley dared not take her dachshund for a walk because it was a German dog. There were nasty scenes in Keighley, German shops burned.’

‘Do you believe someone might have harmed your father because of his friendship with von Hofmann?’