Eighteen years ago, the prehistoric past collided with the present as time itself underwent a tremendous disruption, transporting huge swaths of the Cretaceous period into the twentieth century. Neighborhoods, towns, and cities were replaced by dense primeval jungles and modern humanity suddenly found itself sharing the world with fierce dinosaurs. In the end, desperate measures were taken to halt the disruptions and the crisis appeared to be over.

Until now.

New dinosaurs begin to appear, rampaging through cities. A secret mission to the Moon discovers a living Tyrannosaurus Rex trapped in an alternate timeline. As time begins to unravel once more, Nick Paulson, director of the Office of Security Science, finds a time passage to the Cretaceous period where humans, ripped from the comforts of the twenty-first century, are barely surviving in the past. Led by a cultlike religious leader, these survivors are at war with another sentient species descended from dinosaurs.

As the asteroid that ends the reign of dinosaurs rushes toward Earth, Nick and his allies must survive a war between species and save the future.

Prologue

It has been eighteen years since the planet was swept by time waves, intermixing the Cretaceous and modern periods. In that disaster, whole cities disappeared, never to be seen again. Millions of people were displaced in time, their homes and businesses gone with them and replaced with dinosaur-infested forests. Some called it God’s punishment, but the investigation of the disaster eventually linked the catastrophe to the testing of nuclear fusion weapons in the fifties and sixties.

To detonate a fusion bomb, the heat and pressure of a fission explosion is used to fuse hydrogen atoms, to produce helium atoms, resulting in the release of massive amounts of energy. The resulting thermonuclear explosion sends out several destructive waves, including electromagnetic, blast, and thermal. Unknown at the time of fusion testing was the existence of a fourth wave: a ripple in time and space. While a single time wave was insufficient to cause more than localized time effects, the convergence of several time waves accounted for the worldwide disruption of the space-time continuum.

As civilizations have done for centuries following catastrophe, people adapted to the losses, rebuilding their homes, their highways, and the railroads. Power grids were restored, and holes in the data networks filled. Cities sprouted in and around the chunks of Cretaceous wilderness. Economies boomed as unemployment dropped to record lows and resources poured into urban renewal. As civilization recovered, the most difficult problem was what to do with the dinosaurs.

Some countries exterminated their dinosaurs. Other dinosaurs died naturally, unable to adapt to the climate they found themselves in. Still other countries, like the United States, rounded up dinosaurs, confining them to preserves. Special rangers were recruited and trained, and given responsibility for dinosaur management. Quickly, the people of the world adjusted to cohabiting with the prehistoric animals, and then became fascinated with them. Dinosaur preserves became popular tourist attractions.

Then, ten years after the Time Quilt, as the popular press dubbed the disaster, a group of ecoterrorists infiltrated a secret government project hidden in Alaska. Scientists at the Fox Valley site had created a special pyramid to gather orgonic energy, the same energy used by the Egyptians to help preserve their pharaohs. These researchers had discovered that the pyramid form focused orgonic energy, and by lining a pyramid with a high-tech material, the Fox Valley scientists created a highly efficient capacitor capable of storing orgonic energy. Not widely known at the time was that orgonic energy also influenced the time ripples and could be used to manipulate them.

Taking control of the Fox Valley site, ecoterrorists simultaneously detonated three nuclear weapons, sending the facility back in time ten years, and to the moon. Those three symmetrical and simultaneous explosions also created connections through time and space between the Fox Valley pyramid, the Fox Valley pyramid transported to the moon, and a newly discovered pyramid in the Yucatán. By using the orgonic energy stored in the Fox Valley pyramid, the ecoterrorists were able to manipulate the time waves still rippling across the planet, planning to create a massive new Time Quilt that would shred space–time, jumbling past and present and destroying modern civilization. If successful, the planet would return to a primitive state, where animals would once again thrive. Fortunately, Nick Paulson and his team thwarted their plan, and all three pyramid sites were destroyed.

The public was told the nuclear explosions were terrorist attacks, the attack on the time line classified. Next to the Time Quilt, the terrorist attack paled in comparison, and gradually the public settled once again into complacency, unaware of the damage done to space–time.

Chapter 1

Moon

You look at that photo on my website, and then you tell me there wasn’t an explosion on the moon. You’ve got to start listening to me, America! Wake up! The government blew up a secret alien base on the moon, and it’s time we-the-people know why.

—Cat Bellow, host of Radio Rebel

Present time

Flamsteed Crater, The Moon

“We are approaching the debris field now,” Mike Watson said, his message relayed from his PLSS suit to the lunar lander to the orbiting lunar shuttle and then on to Earth.

As mission commander, Watson led the way, the rest of his crew fanned out behind him. Mission Specialist Sarasa Chandra trailed on his left, Mission Specialist Rick Maven on his right. They used the gentle hopping motion perfected by Apollo crews. In one-sixth gravity, walking quickly became bounding, so planned bounding was more efficient.

Watson checked the radiation reading in his heads-up display. He ignored the UV radiation; his suit could handle routine lunar exposure. What concerned Watson was the particle radiation. The team’s specially insulated PLSS suits would protect them for a time, but Watson kept an eye on the rems. He and his wife wanted more children, and wanted them to have all the usual body parts.

They passed random bits of man-made debris—strips of metal, chunks of rubber, pieces of concrete, the brass knob of a door handle. They came to a larger object—a refrigerator. Dented and half buried, it stuck up out of the regolith like modern art. The door was partially ajar. Watson did not bother to look inside. According to the intelligence briefing, the last residents of the structure ahead had eaten everything. Watson snapped a picture and moved on.

“Over here, sir,” Chandra said.

Watson stopped, turning his shoulders to turn his helmet toward Chandra. She was holding up a long bone.

“It’s a human leg bone,” Chandra said. “It’s been picked clean.”

“Photograph it and leave it,” Watson said.

They kept moving toward the deep shadow of the crater wall, where the structure hid.

“Sir, this might be what we came for,” Maven said.

Again, Watson stopped, turning his shoulders and head. Maven was holding a jagged piece of black material. Watson walked to Maven, Chandra following. They formed a small circle so they could make eye contact. Maven held what looked like a thin piece of black plastic with a dull surface. About a foot long, and eight inches at the widest point, it resembled a piece of ice broken from the surface of a pond. Maven tapped it, knocking off a bit of dust. Taking the material, Watson turned it on its side, seeing that it was made up of a dozen thin layers.

“It’s light,” Watson said, passing it to Chandra.

Chandra held the material close to her faceplate, studying the layers through two sunscreens.

“This is it,” Chandra announced. “This is what they spent a billion dollars to get.”

“Well, that was easy,” Maven said. “And we have rems to spare.” Maven tapped his faceplate where the radiation readings would show on his side.

“That’s half the mission,” Watson said. “Collect more samples as we go.”

Maven put the sample in a bag, labeled it, and then followed the others. They spread out again with Watson in the lead. The regolith was soft, Watson sinking an inch with each bounce, sending up a small puff of dust. When they came to an edge of the rim shadow, Maven stopped them again.

“This just gets weirder and weirder,” Maven said.

Maven had angled away and was now twenty yards to the right. He was standing by a large object, his lunar boot resting on top. With a shove, he tipped the object over.

“It’s a snowmobile,” Maven said. “I don’t remember this in the mission briefing.”

“They told us to expect the unexpected,” Chandra said.

“They tell you that kind of stuff, but you never really believe them,” Maven said. “Until now. A snowmobile on the moon?” Maven mumbled as he resumed hopping.

Watson checked his display. The rems were increasing, but well within the safe zone.

Entering the shadow, they took a dozen bounds before one of the sun shields lifted, allowing them to see farther into the shadow. Now Watson could see the objective. What had once been the most famous building on the moon—and the only building—was now nothing more than two vertical walls marking one corner. They moved forward, Watson’s eyes on the radiation meter. Then he found a body.

“Chandra! Maven!” Watson called, coming to a stop.

His crew hopped over, closing ranks around the body. Any clothing and hair had been burned away. The genitalia was male, the body mummified through the combination of vacuum and UV radiation. Chandra photographed the body. Maven took samples of the regolith around the corpse, storing them in plastic bags. When they were finished, they continued toward the ruins.

“We should bury him,” Maven said.

“And the leg bone we found?” Chandra asked.

“If there’s time,” Watson said, understanding the feeling. Even on the moon, the cultural need to return humans to the soil was strong.

Now well into the rim shadow, another sun shield retracted and they could see even more detail. What had once been a large rectangular structure had exploded, leaving two intersecting walls standing, the tops crumbled, bent rebar protruding from broken edges. What surprised Watson was that anything still stood. According to the mission briefing, a twenty-megaton warhead had destroyed the site.

The rems continued to creep up but nowhere near the level Watson had feared.

“Sir, there are bones here,” Chandra said.

“Photograph them,” Watson said, not bothering to turn and look this time. “We’ll bury them if we have time.”

“They’re not human,” Chandra said.

Now Watson stopped, turning. Chandra held a long thin bone.

“Dinosaur,” Chandra said.

“Snowmobiles and dinosaurs on the moon,” Maven said. “They said expect the unexpected, not expect the weird.”

Moving on, the texture of the regolith changed. Kneeling in PLSS suits was impossible, so Watson used a long-handled scoop to sample a piece of the surface. The material looked like gray straw. It crumpled when touched.

“It think it’s organic,” Chandra said. “It may be grass.”

“Take a look at this,” Maven said.

Hopping over, they found Maven looking at another chunk of the black material they had collected earlier.

“I’m having trouble focusing on this piece,” Maven said.

An eight-inch chunk of the black material lay on the surface, coming in and out of focus.

“It’s refractive properties keep changing,” Chandra said.

“Mike, this is Mission Control,” a voice cut in. “Do not touch that material. Use tongs and store the material in a lined bag.”

“Tongs?” Maven said. “Now they tell us.”

The team carried special sample bags, now understanding what they were for. Using long-handled tongs, Maven picked up the chunk and dropped it in a bag held open by Chandra. Chandra sealed the bag. She put the sample in a pouch on the side of her suit, and they moved on, now picking their way through chunks of concrete, careful to skirt exposed rebar and other jagged material. The debris here was larger, heavier, the smaller pieces having been blown well across the moon’s surface. Finally, they reached the foundation for the original building. Up close, Watson could see that more of the building stood than appeared from a distance. Concrete several feet high still formed a perimeter. There was a gap near the astronauts, and they carefully worked through concrete chunks toward the opening.

“Sir, look at that,” Chandra said, pointing over the jagged wall.

They stopped to see where Chandra pointed but saw nothing. Then over the broken wall they saw puffs of dust.

“Something’s kicking up dust,” Maven said.

Few things kicked up dust on the moon, Watson knew. Seismic activity could, but they felt none. Meteor impacts also, but the dust they were seeing came regularly, inconsistent with a random micro-meteor strike. Rapid heating of the frozen regolith could cause surface fracturing, but the rim shadow prevented rapid solar heating.

The dust continued to puff.

“Let’s take bets on what’s causing it,” Maven said. “I’ll take a Russian women’s hockey team.”

“Residual volcanic activity,” Chandra said. “Left over from the nuclear detonation.”

“Not weird enough,” Maven said. “Take my word for it, whatever is causing that dust cloud is going to be closer to a Russian women’s hockey team than volcanic activity.”

Watson stayed out of the betting, but leaned toward Maven’s point of view. The path through to the opening was narrow, so they walked single file now with Watson in the lead. Coming to the opening, Watson stopped, the others coming to stand shoulder to shoulder. What they saw left them speechless.

“Impossible,” Chandra said.

“Yeah,” Maven said.

One end of what had been a building was rubble, but in one corner of the remaining wall was a dinosaur, standing on a flat black surface. Not a dead, mummified dinosaur, but a living, thrashing, animal, trying to break free from some invisible restraint.

“That’s a tyrannosaur,” Chandra said.

“No, too small,” Watson said. “That’s Deinonychus.”

“Those are the ones they call ‘dine on us,’ ” Maven said.

“The jaws are too big and the arms too short for Deinonychus. It must be a juvenile tyrannosaur,” Chandra insisted, “or something in the tyrannosaur family.”

“It has to be an illusion,” Maven said. “A projection.”

“Looks real to me,” Watson said.

“What’s holding it?” Chandra asked. “It’s like its feet are glued down.”

Like an animal trapped in quicksand, the tyrannosaur struggled, its tail swinging wide, sending up the occasional cloud of dust.

“Mission Control, are you seeing this?” Watson said.

“Affirmative, Mike,” came the reply. “Do not approach until we advise.”

“No problem,” Watson said.

“How can it breathe?” Chandra asked. “It can’t,” she said, answering her own question. “It shouldn’t even be alive. Nothing can live in a vacuum.”

“It’s alive, all right,” Maven said. “Let’s just hope it doesn’t get loose, or we’ll wish there was a Russian women’s hockey team here to protect us.”

“Look at how hard it’s struggling,” Chandra said. “It should be exhausted.”

“Commander Watson?” a new voice cut it. “This is Nick Paulson. I am director of the Office of Security Science.”

“I know who you are,” Watson said. “What can we do for you?”

Watson knew Paulson through reputation and rumor. By reputation, Paulson was world-renowned for his work on the time quilting that had swept the planet, bringing dinosaurs to the modern world, and was a confidant of presidents. By rumor, Paulson was said to be one of the few people on the planet who knew what was really behind the time distortions.

“Can you probe the surface of the interior without stepping on it?”

“Stand by,” Watson said.

Watson unsnapped the long-handled scoop, extending it full length. Carefully stepping around concrete rubble, he worked his way to the edge of the perimeter. Inside, Watson could see chunks of what once had been a concrete floor. Most of the floor was gravel-size rubble arranged in elongated piles, looking like ocean waves. Watson touched the surface with the scoop.

“It feels solid,” Watson said.

After the long pause for relay to Earth, Paulson came back. “Advance slowly, probing every six inches,” Paulson said.

Watson paused long enough to rotate his shoulders to exchange looks with Chandra and Maven. Maven shrugged his shoulders while Chandra rotated her shoulders back and forth, indicating Hell no. Watson could switch off the Earth link and talk to his team, but decided against it. Having Paulson suddenly commandeer the mission was unorthodox and even weird, but Watson was as curious about the conditions in the interior of the structure as Paulson was. Even without the order, Watson was going in.

Inching toward the still-struggling dinosaur, Watson felt like a soldier probing a minefield. Six inches at a time, he worked toward the dinosaur, always one eye on the tyrannosaur. Suddenly, the carnivore stopped struggling. Cocking its head, it stared at Watson with one eye.

“I think it spotted me,” Watson said.

“Get out, sir,” Chandra said.

“I’m coming in,” Maven said.

“Everyone stay where you are,” Paulson said, stopping Maven as he started into the perimeter. “Keep your cameras on the dinosaur.”

They stood, locked in a staring contest with the tyrannosaur. Then abruptly, it turned its head, using its other eye. Suddenly, it lunged, but the invisible restraints held, and it barely moved. Twisting and turning, it repeatedly lunged, jaws snapping silently in the vacuum.

“Try moving sideways,” Paulson said.

“Moving? I thought prey were harder to see if they didn’t move.”

“Please move sideways,” Paulson said after a long pause. “It’s safe.”

In a PLSS suit, sidesteps were impossible, so Watson turned, hopping to his left. The tyrannosaur struggled another second, and then stopped, cocking its head from side to side as if searching for Watson. Finally, it gave up, ignoring Watson, resuming its frenetic struggles.

“Commander, I won’t ask you to go any further,” Paulson said.

“That thing is cemented in place,” Watson said. “It’s safe enough to get closer.”

“If you are comfortable,” Paulson said.

“Do you have a goal in mind?” Watson asked as he resumed inching forward.

“Yes,” Paulson said. “I would like a sample of the material the dinosaur is standing on.”

Watson studied the predator, estimating the sweep of its tail and the length of its neck. Watson did not think it could reach him.

“You don’t want to get that close,” Maven said.

“I’ll be careful,” Watson said.

Inching slowly, Watson worked his way over waves of rubble, the tyrannosaur ignoring him, still wrenching back and forth violently. Reaching the edge of the black mass the trapped animal stood on, Watson used the long-handled scoop, touching the black material. It was solid. Watson tapped the material and then turned the scoop over, using the serrated edge to scratch the surface. No marks.

“It’s hard like rock,” Watson reported.

There was a long moon-to-Earth pause.

“Try probing it with the orgonic material you collected.”

“Orgonic?” Watson said.

“The pieces of black material,” Paulson said.

“Why?” Watson asked.

A long silence followed. Watson imagined an intense argument taking place on the other end of the Earth link.

“Try the collected samples because they may be made of a related material.”

That explained nothing, but Watson knew he would not get anything more. Maven came forward, detaching his sample bag, offering the first piece of the material they found. Watson snapped the scoop head off his long handle and attached the tongs. Then he used a multitool folded into pliers to extract the material from the sample bag and transfer it to the tongs. Now using the long-handled tongs, Watson touched the material to the surface.

“Same result,” Watson said. “What were you expecting?”

After a long pause, “We’re just experimenting. Try the sample Dr. Chandra is carrying,” Paulson said.

Watson returned the sample to Maven’s bag, and then Maven backed away as Chandra came forward. Using the same procedure, Watson extracted the sample from Chandra’s bag. As before, the surface of the piece was hard to focus on. The tongs gripped it, however, and Watson lowered it to the surface. When the material touched, it slowly sank.

“It’s melding with the surface,” Watson said.

“Extract it,” Paulson radioed after a pause.

“This just gets better and better,” Maven said.

“Major Watson,” Paulson said. “Please collect as much of the black material as you can. From now on, that is the only mission priority.”

“Yes, sir,” Watson said.

“What about the dinosaur?” Chandra asked.

“I say we leave it,” Maven said. “The Russian women’s hockey team will be along soon, and they can deal with it.”

Chapter 2

Pest Control

I did find a statistically significant increase in the number of unlicensed dinosaurs appearing outside of ranges and licensed habitats (see attached). I have not been able to identify the source of these dinosaurs, or a pattern, but I will work on it again next summer if I receive another internship.

—Chad Barrett, university intern, memo, Department of Dinosaur Control

Present time

Hillsdale, Florida

Carson Wills turned his van down the access road, driving through an open security gate onto fresh blacktop. A sign over the entrance read Mills Ranch. “Ranch” was a grandiose term for a weekend farm owned by yuppies. Ahead, a large two-story “farmhouse” sat on the highest point on the property, where the masters could look out on their estate. A large deck on the second story overlooked the pool below and the shallow valley beyond. Carson pictured young executives, girlfriends and trophy wives standing on the deck, drinks in hand, admiring the view of what had once been a productive farm—tomatoes and lettuce, Carson guessed by the look of the fields.

From the deck, visitors would see land that generations of farmers had fought nature for, taming the lush subtropical forest piece by piece, making a living for their families and feeding the state and the nation with year-around crops. The crops, livestock, and sense of purpose were gone, replaced by pastures for horses, llamas, or the newest fad, domesticated dinosaurs. Apatosaurs were the most popular, but only for the very rich. These massive animals with their long necks and tails took more acreage than the Mills Ranch could offer. Smaller sauropods were common on ranches like the Mills Ranch, and even armored dinosaurs like Monoclonius, triceratops, or smaller ankylosaurs. Managing beasts like triceratops was difficult, however, and took a professional staff. Carson guessed these paddocks would hold small sauropods or maybe a hadrosaur, probably a duck-billed hadrosaur.

Carson pulled into the circular drive, parking his cream-colored GMC van next to a red Audi. The decal on the side of his van showed a cowboy lassoing a T. rex. Above the image was painted dinosaur wrangler, the name of Carson’s company. The same cowboy logo was embroidered on the chest of his yellow cotton shirt. For a five-hundred-dollar minimum, plus expenses, Carson or one of his employees would come on call and deal with dinosaurs that had escaped from preserves or broken through fences. Despite the decal, Carson had never encountered a tyrannosaur and never would, since carnivores were strictly regulated. There were only a few in Florida, all federally owned and managed. Private ownership of carnivores was a felony, and there were only two ranges in the United States where they roamed free. The only carnivores roaming free in Florida preserves were small scavengers like the seven-pound Bambiraptor.

Ignoring the brass knockers, Carson rapped on the front door with a knuckle. Marty Mills opened the door, wearing Levi’s and a long-sleeved denim shirt. He was clean-shaved, with dark hair trimmed neat, blue eyes, and a genuine smile that showed off his bright-white teeth.

“Hey, Fanny, the dinosaur guy’s here,” Marty called over his shoulder. “Thanks for coming.”

Marty Mills took Carson’s hand, shaking it and pulling him in at the same time. The entry was walnut hardwood. A staircase led to the second floor, a spacious living room opened to the right, and on the other side, a set of French doors led to a library.

“I’m so glad you’re here,” Fanny Mills said as she came down the stairs. “We called the preserve, but they don’t have any rangers available. They put us on a list.”

Fanny Mills wore cargo shorts with a navy blue polo shirt. She was pretty—very pretty—with short black hair, large expressive brown eyes, and another smile full of bright-white teeth. Her face, arms, and legs were genuinely tan, not the spray-on fake tan that gave you the color without the cancer risk. Coming directly to Carson, Fanny took his hand, shook it, and then held it while she spoke to him sincerely.

“You’re not alone, are you? It’s too dangerous to do it alone. We won’t let you, will we, Marty?”

“No, of course not,” Marty said.

It took Carson a few seconds to realize the Millses were genuinely concerned about his safety. “Mr. and Mrs. Mills,” Carson began.

“Marty and Fanny,” Fanny said, finally releasing Carson’s hand after a final squeeze.

The squeeze gave Carson a warm rush.

“Look, I have been doing this for a long time. Let me take a look at what you’ve got, and if I need help I’ll call in one of my crew.”

“It’s a velociraptor,” Marty said.

“Probably more than one,” Fanny said, taking him by the arm. “They run in packs. Of course you would know that.”

“Velociraptors are illegal,” Carson assured them. “If it’s a carnivore, it’s more’n likely an oviraptor. They keep them in the ranges as scavengers to keep the range free of carcasses. The problem is that they keep escaping because the barriers are built for the big animals. If it is an oviraptor, there’s not much to worry about. Might eat your cat if you have one, but that’s about it.”

“I heard an oviraptor killed a baby in California,” Marty said.

“Urban myth,” Carson said. “Do you have a baby?”

“No, but we’re trying,” Fanny said, taking Carson’s arm, and leading him down the hall.

Fanny and Marty were uncomfortably open, Carson thought, but Carson liked them. The Millses took Carson down the hall to the biggest kitchen he had ever seen, with a breakfast bar and kitchen table. The back wall was glass, with more French doors that opened out to the pool deck. The tile floor in the kitchen was the same as the tile around the pool, so with the French doors open, the pool area and the kitchen would seem to be one large room. There was another set of stairs along one wall of the kitchen, and the Millses took Carson to the second floor and another large open space sprinkled with arcade games and a foosball table. A large wet bar sat against one wall, and another glass wall led out to the deck. Two pairs of binoculars sat on the bar. Marty picked them up, and Fanny led Carson onto the deck.

Fanny was unusually physical for a married woman, holding Carson’s arm, leaning against him, guiding him with a hand on his back. Carson enjoyed the contact, feeling it was somehow illicit. Carson also knew that if the plumber showed up later that day, Fanny would be just as attentive.

“Here you go,” Marty said, handing Carson one of the binoculars. “We saw the velociraptor down the valley by the old barn.”

Marty took the binoculars, following Marty’s point. The binoculars had image-stabilization technology, and the view through the lenses was as stable as looking out a window. Carson found the old barn. It was a half-collapsed structure that looked like a pile of weathered scrap wood.

“We saw it run from the tree line on the south into the barn,” Fanny said.

Carson studied the barn but saw nothing.

“We’ve seen it twice now,” Marty said. “Fanny saw it yesterday early in the morning, and I saw it last night.”

“Have you been to the barn?” Carson asked.

“No!” Fanny said emphatically. “Marty wanted to go, but I said, ‘Don’t even think about it.’ I told him, I said, ‘Marty we need a professional,’ and so we called you.”

“Did you find me in the yellow pages, online, word of mouth?” Carson asked.

“Online.”

Carson made a mental note to drop his yellow pages advertising. Only one call in fifty was coming from print advertising.

They watched the barn for another couple of minutes.

“I’ll go take a look,” Carson said.

“Not alone?” Fanny said, touching his arm.

“No worries,” Carson said, feeling her genuine concern. “I’m a professional.”

The Millses followed him to his van. Carson loaded his tranquilizer rifle with a dosage for an animal the size of an ostrich, still expecting an Oviraptor. Putting on his camouflaged hunting vest, he put a pouch of darts in his shirt pocket, preloaded with a range of dosages.

“Those tranquilizer darts are a lot bigger than I thought,” Fanny said.

“They’re nothing like they show on TV,” Carson said. “Each dart is really a full-size syringe with an explosive charge on the end,” Carson explained as he put on his gear. “The rifle is CO2 powered. I can adjust the power setting so I can shoot an animal from as close as two feet or as far as thirty yards without hurting it.”

Carson opened the rifle, extracting the dart.

“When the dart hits, this blue end compresses and this brass rod strikes the firing pin, setting off a charge. The explosion drives the plunger and injects the drug.”

“Cool,” Marty said.

“How long before the animal is sedated?” Fanny asked.

“Depends on the size of the animal. Too small an animal, and I could kill it with this dosage. Too big, and it won’t go down at all. If the dosage is right, it takes five to ten minutes for the animal to get manageable.”

“Five minutes with an angry velociraptor,” Marty said, whistling.

“It’s not a velociraptor,” Carson said.

“We’re going with you,” Fanny said.

“It can’t be a velociraptor or any of his bigger cousins,” Carson said. “Dinosaur rangers tag any predator, and besides, there aren’t any large predators in the Ocala preserve. If any of the scavengers they do keep start probing the fence line, they put them down. Predators just can’t get loose, let alone this far from a preserve.”

Carson snapped the bag with his throw net to the loop on his left side, checked the load in his pistol, and put it in his holster. Then he took the leash pole—an extendable aluminum pole with a wire loop on the end. With the loop over the head of the dinosaur, Carson could tighten the wire and keep the animal at bay with the pole.

“Aren’t you taking a rifle?” Fanny asked, pointing to the guns hanging on the wall of the van.

“I’ve never had to use one of those,” Carson said, closing the van door. “I’ll take a look in the barn and check the area for animal signs. Depending on what I find, I’ll either handle it or call in for help.” Carson pulled a phone from his vest pocket and showed it to them. “If I need help, it will cost more than the five-hundred-dollar minimum.”

“I would hope so,” Marty said.

The Millses walked with him to the edge of their carefully watered and trimmed lawn and then stood on the edge as he walked down the hill into the valley leading to the old barn.

Most of the former lettuce and tomato fields spread across the valley to the north. The pastures were to the south. Carson skirted two pastures green enough for Kentucky thoroughbreds and then through the scrub growth beyond. Ahead to the south, Carson saw the original farmhouse, its windows and doors boarded. The barn sat a hundred yards behind the house. The barn was in bad shape, the end nearest Carson partially collapsed. The rest of the structure still stood but listed to the south, looking ready to fall at the slightest breeze. Given the regularity of hurricane winds in Florida, it was a miracle the structure still stood.

Carson slowed his pace, now choosing his footing to avoid sticks and dried leaves. Approaching the barn, Carson paused often, listening. With virtually no breeze, there was no downwind approach. Assuming the barn was as boarded up as the old house, Carson crept to the collapsed end. Part of the wall was gone, leaving a hole he would have to duck through. That was good, since only a medium-sized animal could get through the opening. He did not want to come face-to-face with triceratops with only a dart gun and a leash pole.

Waiting and listening, Carson heard nothing and saw nothing. Then he duck-walked through the opening, the tranquilizer rifle in one hand, and the leash pole in the other. Inside, he stood and moved right until he could stand with his back against a portion of the wall. Waiting for his eyes to fully adjust, soon Carson could make out details. The floor was dirt, giving the interior an earthy smell mixed with the stink of manure. Light leaked through cracks and joints, illuminating slivers of the interior but creating deep shadows too. Looking around, Carson found the interior disequilibrating, the slanted barn boards giving the illusion that the floor of the barn was tilted. There was little left in the barn except for a pile of blue plastic crates, a stack of hay bales, some circular saw blades hanging on the wall over a workbench, and a pair of snowshoes hanging from a ceiling beam. A set of dilapidated stairs led to a loft. Under the stairs was a pile of hay that looked out of place.

Alert for any movement, Carson walked to the hay pile. The mound was roughly circular and filled with a mix of straw, dried leaves, and dirt. Carson leaned the leash pole against the stairs, then squatted, digging into the mound. It was warm. Upon feeling an object, he pulled it out of the pile. It was a brown oblong egg. An egg like he had never seen before.

“Shit!” Carson said, shoving the egg back into the mound and standing, grip tight on the gun.

Sweeping the room with his tranquilizer rifle, he calmed down. The barn was empty, and even if the animal nesting in the barn was an Oviraptor, Carson could shoot it and fend it off long enough with the leash pole for the tranquilizer to take effect. He felt like an old woman for being so nervous. All the talk about a velociraptor by Fanny and Marty had put him on edge. Turning back to the nest, Carson studied it, trying to remember if he had ever seen an oviraptor nest before. Then he heard movement behind him.

Turning, Carson saw a velociraptor trot out of a dark corner of the barn. Spotting Carson by the nest, its head went low and its tail straight out. Hissing, it cocked its head back and forth, sizing up its target.

Velociraptors were small predators, this adult about the size of a German shepherd, but equipped with curved claws used to slash prey to ribbons. Carson was six feet tall and 190 pounds, just big enough to give the velociraptor pause, but not for long. Velociraptors could bring down prey several times its own size. Slowly raising his tranquilizer rifle, Carson backed up, making sure when he moved, he moved away from the nest. The velociraptor continued to hiss, watching Carson’s movements, sizing him up, plotting an attack. Fanny had been right when she said velociraptors hunted in packs. They also nested in pairs. Carson had to get out of there before the mate showed up.

In his peripheral vision, Carson saw the stairs. Guessing the barn doors were nailed shut, Carson backed up faster, never taking his eyes off the hissing velociraptor. Before he got to the bottom of the stairs, another velociraptor trotted out of the shadows of the collapsed wall. This velociraptor was larger, the size of a Rottweiler, and just as fearless. Assuming the attack posture, it was more impulsive than its partner. It charged.

Carson shot it in the chest. The rifle was set for a fifteen-yard shot, and at this range the hit and explosion of the dart surprised the velociraptor, knocking it out of its charge. Spinning, the velociraptor reached for the dart with its jaws and then clawed with a foot. Carson turned, took two steps, and climbed onto the stairs. The smaller velociraptor jumped onto the stairs just behind Carson. Carson threw his rifle. The velociraptor caught the rifle in its jaws and twisted its head, the rifle coming free, clattering down the stairs. Carson pulled his pistol and shot the velociraptor three times at near point-blank range. Squealing, it snapped at Carson and then twisted, clawing at its chest, falling off the stairs.

Taking the stairs two at a time, Carson reached the top. The clicking of claws alerted him, and he turned just in time to see the larger velociraptor jump into the loft, a hypodermic dart hanging from its chest. Carson fired twice but missed the moving target. Surprised by the crack of the gunshots, the velociraptor retreated toward a dark corner. Carson fired again, the shot splitting a barn board, releasing a sliver of sunlight. Carson looked around. The loft held ancient hay bales but nothing else. There were double doors. Carson ran to the doors, finding a bar holding them closed. After lifting it out of the brackets, Carson shoved, the doors swinging open on rusty hinges. The blast of sunlight blinded him. Blinking, he turned, seeing the velociraptor crouched in a corner. Blinking furiously, Carson fired again, then sat with his feet dangling, holstered his pistol, and then grasped the edge of the opening, lowered himself, hung for a second, and then dropped.

An ankle crumpled when he hit—sprained but not broken. Lying on his back, Carson saw the velociraptor leaning out the opening, estimating the drop. Then it turned, disappearing inside. Carson got to his feet, limping back the way he’d come. Pulling his pistol, he aimed it at the opening in the collapsed end of the barn. He was just past the opening when the velociraptor shot out of it. Carson turned to fire, but hitting a target as fast as a velociraptor with a pistol was almost impossible. Carson stumbled, turning, falling to his back, bringing the pistol up. The velociraptor jumped feet first, raking claws extended. Carson fired and at the same time Carson heard two almost simultaneous gunshots. The velociraptor was shredded midair, landing next to Carson, dead.

Carson got to his feet. The Millses were behind him, each carrying a smoking shotgun.

“I told you it was a velociraptor,” Marty said.

“And I told you we wouldn’t let you go alone,” Fanny said.

“I had it under control,” Carson said, limping toward them. “I’m a professional.”

“Any more in there?” Marty asked.

“One other. It’s dead.”

The Millses came to look at their kill. Carson looked the velociraptor over, searching for a tag—he could not see one.

“Where is the tag?” Fanny asked, squatting by the velociraptor.

“It’s subcutaneous,” Carson said, telling a half-truth. “The carcass has to be returned to the Park Service or you would have yourself a nice trophy.”

“I thought you said there weren’t any velociraptors at the Ocala Preserve,” Marty said.

“Must’ve brought a couple in. They’ll get rid of them for sure now. I’ll go get my van and clean up the site,” Carson said, not mentioning the eggs.

“Lunch first,” Fanny said. “I’ve got steaks in the fridge.”

“And beer,” Marty said.

“Sounds good,” Carson said, distracted by the thought of the eggs.

The Millses were paying five hundred dollars for the job, but each egg was worth ten times that much on the black market—maybe more. The beer was cold, the steaks were thick, and by midafternoon, the velociraptor carcasses and the eggs were safely stowed in the Dinosaur Wrangler van and on the way home.

Copyright © 2012 by James F. David.

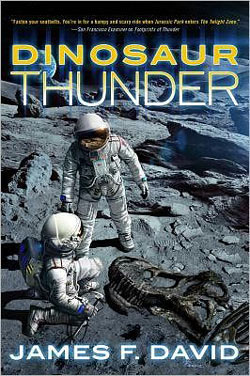

James F. David has a Ph.D. from Ohio State University and is currently Dean of the School of Behavioral and Health Sciences at George Fox University in Newberg, Oregon. He is the author of the dinosaur adventures series that includes Footprints of Thunder, and Thunder of Time, and the thrillers Ship of the Damned and Before the Cradle Falls, as well as the Christian rapture series that begins with Judgment Day. He lives with his wife in Tigard, Oregon.