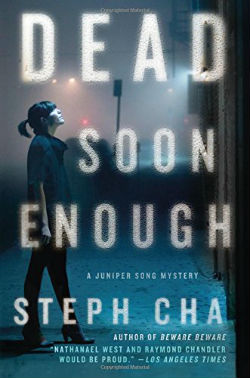

Dead Soon Enough by Steph Cha is the third mystery featuring Los Angeles P.I. Juniper Song who has finally just received her detective's license (available August 11, 2015).

Dead Soon Enough by Steph Cha is the third mystery featuring Los Angeles P.I. Juniper Song who has finally just received her detective's license (available August 11, 2015).

Juniper Song is managing her own cases as the junior investigator of Lindley & Flores. When a woman named Rubina Gasparian approaches Song, she knows she's in for her most unusual case yet. Rubin and her husband Van-both Armenian-American doctors-cannot get pregnant, so Rubina's younger cousin, Lusig, is acting as their surrogate. However, Lusig's best friend Nora has been missing for a month, and Rubina is concerned that her nearly eight-month-pregnant cousin is dealing with her stress in a way that could harm the baby. Rubina hires Song to shadow her and report all that she finds. Of course, Lusig is frantically searching for Nora, and Song's case soon turns into a hunt for the missing woman, an activist embroiled in an ugly, public battle over the erection of an Armenian genocide memorial. As Song probes the depths of both the tight-knit Armenian-American community and the groups who antagonize it, she realizes that Nora was surrounded on all sides by danger. But can she find out what happened before it's too late for Nora or Rubina and Van's child-or for Song herself?

One

When I was twenty-two, I sold three sets of eggs for a total of $48,000. I was broke, bored, and quietly depressed, and had no strength to fight the call of easy money. It was a questionable decision, but I’ve made enough of those that this one doesn’t keep me up at night.

I’d seen advertisements for egg donors in the Yale paper, but back then I was still on the payroll of a hardworking immigrant mom who saw no better way to spend money than to push her shitty kid through the Ivy League. The ads made a bit of a splash in cafeteria conversations, but as far as I knew, no one really responded. We had a whole campus full of prestigious eggs and, in aggregate at least, a brash imperviousness to financial pressure.

That changed for many of us soon enough. I left Yale with an attractive diploma, an unattractive transcript, and zero to negligible job prospects. I moved to L.A., not because I had dreams, or even family anymore, but because it was a city I knew, one that I liked better than others.

One day, after pinning tutoring fliers in coffee shops full of dead-eyed college graduates just as unemployed as I was, I came across a New York Timesarticle about Asian-American egg donors. Apparently, our eggs commanded high premiums for rarity on the market—Asian-American women waited longer than average to have babies, chasing those professional dreams with their biological clocks ticking softly in the background.

It was like a help wanted ad singing my name.

There was another reason, too, an enabling reason if not an actual impetus—despite my sadness and weakness of spirit I felt, in a way, invincible. It wasn’t that I relished the idea of my spawn running the earth. The truth is, I didn’t think about that much at all. I was young and cavalier, with a disregard for consequences that had almost nothing to do with reality, mine or anyone else’s. Consequences were things that happened to other people. What happened to me was bad luck.

So I did some research and sold my eggs to the highest bidder. They went out into the world, and maybe some of them became people.

I hadn’t thought about them in a long time, and then I met Rubina Gasparian.

* * *

It was a warm Tuesday in early March, one of those pre-spring Los Angeles days that knocked an unnecessary nail into winter’s coffin. I’d had my private investigator license for almost a year, and during that time I’d made a steady, honest living, as free of mishap as any period in my adult life.

When I got to the office that morning, there was a woman waiting outside the locked door. She was standing straight, facing the hall, and when I looked up from my phone she was already watching me, waiting for me to acknowledge her. I nearly jumped.

She was a slim woman wearing a gray wrap dress and short, professional heels. I was almost a head taller, even in flip-flops, but there was something commanding in her presence that negated the impression of smallness. She was pretty in a brutal way, with a high forehead, straight black hair, and an immaculate gloss to her pale skin. Her eyes were sharp and dark, and by the time I got around to greeting her, they’d run their way right through me.

“Hi,” I said. “Are you looking for Lindley and Flores?”

“Yes. I hope you don’t mind my coming in so early. I don’t have an appointment.” She spoke quickly, but with a tentative, deferential tone of voice.

“Not at all. I’m Juniper Song,” I said, holding out my hand. “I’m an investigator.”

“Rubina Gasparian.” She shook my hand with a firm grip, and I felt the press of a ring on my palm. Wrong hand for a wedding band, but I saw that she had one of those on, too. “It’s nice to meet you.”

I opened up the office and Rubina followed me inside. I sat down at my desk and, before I was able to offer, she took a chair across from me.

“So, Ms. Gasparian. What can I do for you today?”

“It’s Doctor,” she said, then added, “Though that doesn’t matter.”

“Sorry.” I smiled, feeling mildly caught off guard. “Dr. Gasparian, what can I do for you today?”

She crossed her legs and folded her hands over the top knee. “I’d like to hire someone to follow my cousin.”

“We can certainly do that,” I said. “All three of us are seasoned tails. That’s kind of the bread and butter of this job. What can you tell me about her?”

She produced a 4 x 6 photograph and pushed it delicately across the desk. It was a professional photo of Rubina in a wedding dress, with one arm around a younger woman in a lavender dress, unmistakably a bridesmaid. I took a long look at the cousin. She had the same pale skin and round eyes as Rubina, but she gave off a rugged impression, even in pastel chiffon. Her bare arms showed a colorful splash of tattoos, and her shoulders were broad and well honed. She wasn’t as traditionally attractive as Rubina, but she would never fade standing next to her.

“That was taken on my wedding day, almost six years ago. The girl on my left is my cousin Lusig. I can e-mail you a more recent photograph—her hair’s much shorter now, and she has a piercing in her nose, which I made her take out for the wedding.” She paused and nodded, making a note to herself. “I’ve known her since she was in my late aunt’s womb. She’s a wonderful girl. I love her like a sister and daughter, and now, she’s carrying my baby.”

“How’s that?” I asked.

“For a few reasons, chief among them that I am thirty-seven years old, my husband and I are unable to conceive. Since we want children, and adoption is out of the question, we decided on a gestational surrogate.”

I wondered briefly why adoption was out of the question, and something in Rubina’s eyes dared me to ask. It didn’t seem like my business—not that that always stopped me—but I bit.

“Why was adoption out of the question?”

“Here are two clues,” she said, holding one hand up in a V. “My married name is Gasparian. My maiden name is Balakian.”

“You’re Armenian,” I said. Armenian surnames were almost as easy to spot as Korean ones.

“Very much so. And as an Armenian couple, Van and I would like to continue our bloodline. There are only so many of us left.”

“Forgive me if I’m off track here. Been a long time since World History. But you’re referring to a genocide?”

She nodded. “Of course. It’s telling that you’re uncertain. Not—” she added hastily—“telling of your ignorance, but of the Armenian genocide’s status in history. But that is a long conversation, and we were already in the middle of another one.”

“Right,” I said. “You were telling me about a gestational surrogate. That means what, your egg, her womb?”

“Yes.”

“And that surrogate is your cousin Lusig.”

“Exactly.” She smiled, lending a little warmth to her features. “Lusig wasn’t ideal in every way. The perfect surrogate is a woman who’s been pregnant before, who won’t form an undue attachment to the baby. We think Lusig will be fine with giving him up, but this is her first pregnancy, and she had no familiarity with the process before she agreed to sign on.”

“So why her?”

“First, she offered. She knew we needed help, and she said she was more than happy to. Second, Lusig and I are very close. She would be in the baby’s life, as more than an aunt, if a little less than a mother. Third, Lusig has no desire to have children of her own.”

“How old is she?”

“Twenty-six.”

“Early to make that call, wouldn’t you say?”

Rubina shrugged, a small, mechanical motion. “She’s maintained this position for many years. Lusig is a headstrong, stubborn girl, and she is not known to change her mind. On top of which, she’s unmoved by children, and thinks she would make a poor mother. Between you and me, I agree with her.”

“Why’s that?”

“Well, practically speaking, Lusig has never been employed for more than a year at a time. She has very little interest in figuring out her life, and I can’t imagine she’d have room for a child anytime soon. And I know she’s young, but twenty-six is not twenty-two.”

I suppressed a smile. Rubina could have been describing me before I started working for Chaz. I’d spent my post-college years tutoring around the city for bursts of cash, just enough to pay rent and maintain my pantry and one shelf of my fridge. Pregnancy would have been a nightmare.

“What’s she do?”

“This and that. Temp work, mostly. Sometimes she participates in psych studies and focus groups. She lives at home, with her father, so her living expenses are very low. We’ve been paying her a stipend while she carries the baby, so she isn’t working now.”

“None of this sounds particularly permanent,” I said. “You think she’ll always be unfit for kids?”

“I love her, but she’s a selfish girl. She’s a classic only child, not conceited but very self-centered. She’s always surprised to recall that the world doesn’t revolve around her.”

“I don’t think I’m especially selfish, but I would run far away if anyone wanted to borrow my body for nine months.”

“Of course she’s often generous. Maybe this is getting lost, but I think Lusig is wonderful. She’s only fundamentally selfish.”

I nodded, wondering how damning this was supposed to be. “Is that why you’re here?”

She gave me a thoughtful stare before speaking again. “I suppose it is,” she said. “I’m worried that she’s putting herself before the welfare of my child.”

“How so?”

“She’s almost eight months pregnant, well past the initial touch and go. Not that this pregnancy could ever have been less than a deliberate, serious affair, with all the money and energy poured into it from the beginning, but my son is more baby than fetus now. He will be born. I’m going to be a mother.” She looked pointedly at my left hand. “You don’t have children, Miss Song?”

“I have not been so blessed,” I said. “You can call me Song, by the way. Though ‘Miss’ is correct.”

“I’ve always wanted to be a mother. I waited longer than I ever thought I would, but I went to medical school, then did my residency, then a fellowship, and before I knew it I was looking at limited options. If you’re open to some friendly advice, I’d suggest you not wait too long.”

The conversation was taking a weird turn. Rubina was not the type of woman who inspired quick and easy confidences, and I was more guarded than most. There was a clinical, universal tinge to her prescription, but it still struck me as somewhat intrusive. I ignored it and pressed on.

“So why are you worried about your cousin, Dr. Gasparian?”

“You can call me Rubina,” she said. “I’m sorry I corrected you. It’s a strange reflex.”

“Sure. Rubina. Tell me your concerns about Lusig.”

“She was a party girl. Through college, through her early twenties. And she’s only twenty-six, so her early twenties were not very long ago. We’ve been Facebook friends for years, and I’ve seen all her pictures, drinking and carousing with friends. Nothing abnormal, understand, but she’s always inclined toward the wild side. Nightclubs, vodka shots. I suspect some illicit drugs.”

I pictured Rubina culling through her cousin’s Facebook page, before and after entrusting her with her baby. The picture came easily.

“Drinking and carousing with friends seems pretty standard, really,” I said, though I suspected as I said so that Rubina’s youth had been tame and studious. “And from what you’re saying I gather she got a lot of that out of her system well before she got pregnant. I imagine you wouldn’t have chosen her if you had any doubts. What changed?”

She seemed surprised by the question, but recovered quickly. She tucked her hair behind her ear with a swift, precise motion. “Lusig’s best friend is a girl named Nora. They’ve known each other since the seventh grade—they’re both Armenian, both only children, and they stuck to each other from the beginning. I’ve met her several times, though I can’t say I know her very well. In any case, Nora has been missing for almost a month.”

I sat up a little straighter. “Missing? Like, officially? The police are looking for her and all that?”

“Yes, the police are looking for her. No one has said so, but everyone always suspects the worst.”

“I see,” I said, blinking hard. Murder had just entered the conversation.

Rubina broke the silence before it could set. “But I’m not here about Nora. I’m only giving you background. My concern is that Lusig has been acting strange ever since the disappearance.”

“Strange, how?”

“She’s been moody, and it’s been hard for me to reach her.”

“She’s been off the radar?”

“Not exactly. Let me explain myself.” She gave me a tight smile. “In general, I don’t care what other people do with their lives. Lusig is my cousin, and we’ve always been close, but I haven’t agreed with every one of her life choices. She hasn’t asked me about most of them, and I’ve withheld unsolicited advice on many, many occasions.”

I nodded. Something in her tone suggested unreasonable pride in her own restraint.

“But when you’re pregnant, you don’t own your body, at least not one-hundred percent. This might be especially true if you’ve signed on to be a vessel for someone else’s baby.”

My mind revolted against the idea, but I couldn’t say it was without truth. Instead, I asked, “Then, who does?”

“Who does what?”

“Who owns your cousin?”

“Well, to be frank,” she said, twisting her fingers together, “I think I do.”

I let her statement ride a brief pause, and she let out a tight little laugh.

“I don’t mean she’s my property, per se. And I know in this day and age women have certain rights to their own bodies, which I support wholly. But in this situation, I believe I have an unusual amount of interest in the contents of her womb, don’t you agree?”

“That’s true,” I said, and decided to get back on track. “So, your cousin hasn’t been attentive to your demands as the mother of the child.”

“No. She’s been defiant and unpredictable, going on errands she doesn’t care to explain and snapping at me when I ask where she’s been.”

“It sounds like she has some reason to be upset,” I said.

“Of course she does, and I’d like to give her space to deal with her … grief, if that’s the right word for it.”

“On the other hand?”

She pressed her lips together. “On the other hand, I need to know if she’s mistreating her body.”

“Ah, so this is where I come in.”

“I don’t want you to bother her,” she said. “Please just observe her, tell me what she’s doing, take pictures as you deem appropriate or necessary.”

“Sure, I can do that. Out of curiosity, though, what if I do find out she’s slamming shots and sharing needles?”

“I will cross that bridge only if necessary.”

* * *

I’d been surveilling people for a couple years now, and it had long since started to feel like a creepy second nature. I could follow any car across town at any time of day, and I developed a talent for blending into most environments, without the assistance of a trench coat or a fedora. Most people don’t suspect they’re being followed. After all, hiring a private investigator to solve a personal problem—sussing out infidelity being the classic case—is a somewhat nuclear option, one that many can’t imagine using themselves. I couldn’t follow a man into a public restroom and take a video of his stream, but anything short of that was more or less possible.

Still, some assignments were trickier than others. I wasn’t quite ballsy enough to attempt a nighttime tail on a quiet road, but empty bars were usually manageable. Being an Asian woman worked in my favor—despite my height and somewhat unforthcoming demeanor, no one ever thought I was dangerous.

Lusig Hovanian was going to be an easier mark than most, and not because she was oblivious. Rubina, as I might have expected, kept her cousin on a short leash. Within a few hours of leaving my office, she e-mailed me a complete schedule of Lusig’s day. She gave me the name and address of a restaurant in South Pasadena and requested that I eat there at seven o’clock. She gave me a fifty-dollar stipend—she’d researched the restaurant and determined that this was enough to cover dinner for two. She thought, correctly enough, that I’d stand out less if I wasn’t eating alone.

There weren’t too many people I wanted to meet for dinner, so I was happy that my roommate was free. Lori Lim was my best friend, an adopted younger sister of sorts, with whom I had almost nothing in common but a few shared episodes of extreme trauma. We’d been living together for about two years, in a two-bedroom apartment in Echo Park. I liked to think this arrangement was for her benefit, but we both knew I’d be lonely as all hell without her.

She was also pretty useful as a plus-one on stakeouts, not that she always knew when we were on one. She disapproved softly of my PI work, maintaining that it was unsafe. Fair enough, really, as I’d been drugged, threatened, and held at gunpoint since I’d met her, among other things. But even she recognized that my experience had been largely atypical, and most days she was content to leave me be.

Manhattan Bar & Deli of Pasadena was a cozy neighborhood place, and I guessed from the name that it was run by newish immigrants. I felt minorly vindicated when we were greeted by a middle-aged Chinese woman with halting, friendly English.

Lusig was already seated when we arrived. The restaurant was small and relatively empty, so I spotted her right away. She looked less fresh than she had in Rubina’s wedding photo, though this, of course, was understandable. She was younger then, but I suspected the difference was due more to pregnancy and lack of makeup than to advancing through her mid-twenties.

Nothing about her appearance suggested an ideal surrogate mother. She looked slovenly and unnurturing, like she could hardly bother to take care of herself. Her hair was dyed crow black and cropped messily above her chin. It looked choppy and unwashed, with an oily shoe-polish shine. She wore a black T-shirt under a bulky military jacket big enough to hide a boar. Her ears were studded up and down with a spray of metal and stone. A tiny bright dot adorned one side of her thin nose, and above it, her huge, wild eyes were the focal point of the room.

Lori and I sat at a nearby table, within comfortable eavesdropping distance. I glanced at the young man sitting across from Lusig. He was clean-cut and handsome, with the kind of nonthreatening face that did well with mothers. He had dark hair, thick eyebrows, and sideburns that looked difficult to groom. Lusig had his full attention.

I ordered a hot pastrami Reuben and Lori got lox and cream cheese, which she formed into bite-sized bagel sandwiches, setting one on my plate. Fifty bucks left beer money, so I had a pint while Lori tucked into a milkshake. I told her it was my treat, and she thanked me with unnecessary enthusiasm.

She chattered about her job and her boyfriend Isaac, and I gave her the greater part of my attention while keeping one ear open to receive any revealing tidbits from Lusig’s table. Lusig had a low, steady voice that cut across space without apparent effort. It was easy to track, even while carrying on my own conversation, and when I heard a change in tone and tempo, I pretended to devote all my energy to my sandwich. The small talk was over.

“I’m sorry I haven’t been able to meet you till now,” she said with a note of remorse.

The man laughed uncomfortably. “You’re eight months pregnant, and I know this hasn’t been easy for you, either.”

“No, it hasn’t. To be honest, it had nothing to do with pregnancy. There is nothing easier for a pregnant woman than to eat a pastrami sandwich.”

He laughed again, but stopped when she didn’t join him. “Okay,” he said instead.

“Do you want to know the truth?” she asked.

“Of course.” He didn’t sound especially excited to know the truth.

“I was mad at you.”

“Mad?”

She stared at him across the table, her eyes searching his. “You didn’t keep her safe, Chris. You were supposed to be there for her, that was the whole”—she made a framing gesture with her hands, encompassing his figure—“point of you, and you didn’t keep her safe.”

He moved back in his seat, dragging his chair a few loud inches across the floor. “I didn’t keep her safe? You have some nerve, Lusig.”

She watched him closely, and then her expression softened, taking on the contours of contrition. “I’m sorry. I’m projecting, I know.” She shook her head and looked disapprovingly at her dinner, then looked up again at her companion. “Where do you think she is, Chris? Where could our girl have gone?”

Chris was slumped over, looking helpless and crestfallen, and as I waited for him to answer, I noticed Lori was raising her eyebrows across the table.

“Unni,” she said. “Are you listening?”

I made a show of chewing and swallowing the bite of sandwich in my mouth. “Sorry, I zoned out a little.”

She shook her head and bit her lip with her crooked tooth. “Unni, are you working right now?” she whispered.

“Shhhhh,” I said, widening my eyes. “Jesus.”

“I knew it.”

“I’ll tell you about it later, okay? Sorry, what were you saying?”

She twisted her lips, but I could tell she wasn’t really annoyed. She was used to my work mode after living with me for so long. Our friendship was also the only good remainder of a case that had left us both devastated, and she knew that the job stabilized me, even if she didn’t understand how.

“I was just asking if you’d noticed how much time I’ve been spending at Isaac’s.”

“I am a detective, Lori.”

She’d been spending most nights at Isaac’s for the better part of a month. He’d moved into his own place downtown, and suddenly he was less interested in sleeping in my apartment. I hadn’t seen his face at all for a couple weeks, and even Lori was scarce. His place was within walking distance of her job—she worked in human resources for an accounting firm—and she only seemed to stop home for an hour or two here and there to pick up clean clothes and make sure I had enough to eat.

“Do you mind?” she asked.

I smiled, a little wider than felt sincere. “You’re an adult, Lori. I don’t stay up all night worrying about you.”

“I know, but you aren’t too lonely?”

I shrugged. “No, not too. I’m good at being alone.”

She nodded, still looking solicitous, but she changed the subject.

It wasn’t long before Lusig reclaimed my attention, along with Lori’s and everyone else’s in the restaurant. Her voice was raised, and she was glaring at the waitress.

“Guess what’s none of your fucking business,” she said.

The waitress looked around the room. She was a small Chinese girl, about college-age, probably the owners’ daughter. She wore a Manhattan Bar & Deli T-shirt over slim blue jeans and dainty shoes. Her face twisted into a look of scorn that searched for validation as she scanned the restaurant.

“You’re acting very belligerent,” said the waitress.

“Am I? I’m sorry. I just thought I could order a beer without being interrogated.”

“I only asked if you were pregnant.”

“Sure. Not a loaded question.” She scoffed. “Of course I’m pregnant. Look at me. You knew I was pregnant, so don’t fucking pretend you were just being curious.”

“I don’t know if I’m comfortable serving alcohol to a pregnant lady.”

“It’s a beer.”

“You’re acting pretty drunk already.”

Lusig stood up, rising a half head taller than the waitress, who seemed stunned to have this irate customer glaring down at her face. “I’ve had five drinks in the last three months, you judgmental cunt.” She flung a twenty-dollar bill on the table. “Come on, Chris. Let’s get out of here.”

Chris gaped at the scene in front of him, and then stood up after Lusig, half bowing with apology. He left more bills on the table in a quiet hurry, then followed her out of the restaurant.

The door swung closed with a tinkle of bells, leaving an awed silence in its wake. The waitress stared at the door with her mouth hanging open.

I caught Lori’s eye, and we both covered our mouths to suppress overt laughter.

“Oh, unni,” she said. “Please tell me you were here to watch them.”

I shrugged, and a sly smile spread across her face.

“She’s fun,” she said. “This could be a good one.”

* * *

I couldn’t exactly leap from the table and follow Lusig to her car, so I texted Rubina to report that she’d left. I told her to let me know if she couldn’t get hold of Lusig, and after a minute, she ascertained that her cousin was on her way home. I convinced Rubina she could wait for my report until I was done eating. I finished dinner with Lori and called from the car. She picked up immediately.

“Did something happen?” she asked by way of greeting. “She’s in a terrible mood.”

“She did storm out of the restaurant,” I said.

Rubina sighed. “What did she do?”

I told her about the scene in the deli.

“I told you she was behaving strangely,” she said. “She’s always been a passionate sort of girl, but she usually has good control over her temper. She’s not one to make a fool of herself in public.”

“In my opinion, the waitress was being unreasonable and kind of insulting.”

“That’s no reason to make a scene.”

“Are you upset about the beer?”

“Yes.”

“I thought the occasional beer was pretty much harmless.”

“I know what it says on WebMD, but I also know many, many doctors who have had children. Every one of them abstained during pregnancy.”

I thought about nine months without alcohol, the first big sacrifice forced on new mothers. It seemed daunting to me, even with ordinary levels of stress.

“She said five drinks in the last three months. That doesn’t seem dangerous or anything.”

“It’s the attitude. She’s not acting like a woman putting another’s needs before her own. And I don’t really believe she’s been careful enough to count.”

“I don’t know, she sounded pretty indignant. I’ll bet she’s been counting, even if it’s with some measure of resentment.”

She sighed. “And who was this man she was meeting? Did he look suspicious?”

I almost laughed. There was something childish in the question. “His name is Chris. I was going to ask if he was someone you knew.” I paused and decided to add, “It sounds like he’s involved with Lusig’s missing friend.”

”She didn’t tell me she was meeting him.”

“Who did she say she was meeting?”

“A friend from college.” Rubina sounded dissatisfied. “Which wasn’t a wholesale lie. She and Chris were at USC together.”

“But not exactly the truth, I take it.”

“No. He’s Nora’s boyfriend.”

“It doesn’t seem off or anything, that her boyfriend and best friend would spend some time together.”

“Maybe not. But I know they aren’t close friends on their own.”

I pictured the two of them, Lusig with her tattoos and oily hair, Chris in his square gray polo shirt. They didn’t look like two birds of a feather. Then again, I thought of my friendship with Lori.

“Shared experience counts for something,” I said. “They both love Nora, and she’s gone now.”

“I would go as far as to say that they dislike each other.”

“She’s talked about him with you?”

“Many times. She adores Nora, and she has always thought Chris was a cold, condescending misogynist. Chris, on the other hand, seems to think Lusig is a deadbeat, a bad influence. He blames her for Nora dropping out of law school. I’m sure both of them have better shoulders to cry on.”

There was something suggestive in her tone. “What are you worried about, Rubina?”

“I just wonder,” she said. “Do you think she’s looking for Nora?”

“I’ve seen her one time. You’d know better than I do.”

“She was talking about her.”

“Yes.”

“And she was asking Chris where he thought she was.”

“Yeah, that’s true. But what else do you think she’d talk about with her missing friend’s boyfriend?”

“Nothing at all.” Her tone was clipped and a little impatient.

“Oh, I get it,” I said. “You think she was pumping him for information. She thinks he knows something.”

“Lusig must know Nora might be dead.”

“And if Nora was murdered…”

“Yes. Exactly.”

“You think she suspects him?”

“I don’t know,” she said. “But if that is the case, then she was going out of her way to meet a man she judged capable of murder. If she wants to endanger herself, that is one thing, but she is carrying my child.”

“Rubina, I think it’s important to maintain perspective here. She was getting dinner in a public place with a college classmate.”

“You’re right, of course.” Her tone was gentle but unyielding. “Still, there’s no harm in being watchful.”

Two

Chaz was in the office when I arrived the next morning, and I plunked into the chair across his desk with theatrical heaviness.

“It’s hump day,” he said with a tsk tsk. “Not slump day.”

I looked up and raised an eyebrow. “Would you rather I humped the furniture?”

He smirked and shook his head. “Did not think that joke through. Don’t go telling Art I harassed you.”

“Okay, likewise then.”

“So,” he said, after an appreciative moment of silence. “Why the sighs, Girl Detective?”

“I think I’ve been hired to find a missing woman.”

“Sure. We do that. But what do you mean, you think?”

“The client hasn’t come out and said so, but it’s the only thing that makes sense.”

I gave him a rundown of the case, and he nodded along, paying attention.

“It sounds to me like you’ve got a neurotic woman who wants eyes on her most prized possession. What makes you think she wants any more than that?”

“She may not want any more than that, but it sounds like there’s a big underlying problem. I mean, let’s say you have a big scary mole and you go to a doctor to get it removed.”

“Oh, you’re a doctor now?”

“Come on, Chaz, it’s an analogy.”

“You know what I got on the SAT?”

“What?”

He smiled expectantly and let out a loud fart. “Okay, proceed.”

I rolled my eyes. “So you have this nightmare mole, and you want it gone, but you kind of know there’s a good chance something else made the mole pop up in the first place.”

“Like cancer.”

“Yeah, or whatever. But even if it’s just a mole generator, what’s the point of just treating the mole? Wouldn’t you want to know the underlying cause? Isn’t that kind of why you went to the doctor in the first place?”

“Okay, even I can tell this analogy is a mess.”

“But you get what I’m saying?”

“I get it, but you’re not a doctor, and an endangered baby is more serious in its own right than an unsightly mole.”

“Do you remember Rusty Regan and the General? In The Big Sleep?”

“You always bring up that book like I didn’t read it thirty years ago.”

I nodded. “Fair enough.”

“Anyway, what about the Rusty general?”

“The General is this rich old man who hires Marlowe to investigate a blackmailer, but from the beginning, Marlowe knows this guy has a missing son-in-law.”

“Okay, that sounds familiar.”

“Marlowe thinks he’s been hired to find Rusty Regan, and the General keeps denying it and denying it, but of course, in the end, that’s Marlowe’s whole job.”

“So you think you’re supposed to find this best friend.”

“I don’t know. Maybe. It seems more like the kind of thing you’d pay money for than stalking a pregnant lady. Pregnant women can’t be so hard to stalk on your own. You should see this girl. She is out to here.”

“Your client— Does she seem particularly interested in what’s happened to this girl?”

“Honestly? No.”

“Is she callous?”

“She reads kind of cold, and yeah, maybe callous, but that isn’t exactly it. She’s interesting. I don’t dislike her, but she is off. She has this almost socially feral quality, like she’s been caged in her education so long she doesn’t know how to deal with people.”

“She’s an actual doctor, right?”

“Dermatologist.”

“Zit zapper?”

“Sure, but do you know how hard it is to become a dermatologist? You have to crush med school for four years, and then get through a three-year residency. She was probably thirty years old before she even got to breathe.”

He shrugged. “She’s a smarty-pants like you, is that right, Yale-bird?”

“Much smarter than me, probably.”

“Don’t be so modest. She’s just less of a screwup.”

I frowned. I’d gone to an expensive prep school and an Ivy League college, and it was true that I’d never dreamt of becoming a PI when I grew up. I was an introverted kid who had no talents other than studying, and my strict mother gave me a narrow, exalted vision of my professional future. Lawyer, doctor, rocket scientist. Something to let her strut a bit around other Korean moms. My little sister Iris had been less of a nerd, and my mom would’ve been satisfied if she’d become the head designer for Louis Vuitton or Chanel.

None of that quite panned out. Iris killed herself when she was sixteen after a disastrous affair with her history teacher. I was a freshman in college, and it was something of a miracle that I finished school at all. I still loved my mom—I never blamed her for what happened, and I was grateful she didn’t blame me—but we weren’t close anymore. She’d also adjusted her expectations on every category of my life prospects. When I started working for Chaz, she’d been amazed that I had a job with health insurance. If I’d nab myself any kind of man, she’d probably shit herself for joy.

Chaz liked to joke that I was slumming it. Both he and Arturo, the other named half of Lindley & Flores, were products of the L.A. Unified School District. I met a lot of Angelenos in college—my school alone sent eight kids to Yale—but not a single one from our city’s giant public school system, where a quarter of the kids didn’t make it to graduation, let alone a four-year college.

Chaz wasn’t a dermatologist, but he was a success story, more or less. He had a bachelor’s degree from Glendale Community College, and he worked in IT for many years before he got into private investigation by way of computer forensics. He had a wife and two daughters, and he was one of the happiest people I knew. None of this prevented him from making fun of my expensive education, which I’d used to work as a part-time tutor before Chaz hired me to be his gofer.

“So, this doctor, what makes you think she’s looking for the girl?”

“Couple reasons. First, she keeps coming up. Her disappearance is the whole reason Rubina’s even worried about her cousin, and I can’t seem to untangle one girl from the other.”

“And let me guess.”

“What?”

“The second reason.”

“Sure.”

“You think you’re marked for the job.”

I had to smile. When I’d first met Chaz, I’d thought he was an oaf—he’d been tailing me, and I thought he looked like one of the bumbling stooges who got bumped in detective novels. He was bald and fleshy, and he wore high white socks with white tennis shoes every day. He acted like a textbook corny white American dad, telling bad jokes and embarrassing me at every opportunity. It was easy to forget how smart he was, and his quiet bursts of insight still took me by surprise.

“I’ve had a good break since my last gnarly case. It just seems like the universe has been a bit nice to me, don’t you think?”

“Maybe, but you’ve been unluckier than most,” he said. “We don’t catch a lot of homicides in this business.”

“I know,” I said, “but I have a feeling.”

“Yeah, I’m sure you do. Coincidentally, I think you want to go look for this girl.”

“Hey, it’s not like I’m dying for excitement here. I’ve had enough of that for a lifetime.” He narrowed his eyes at me and I shrugged. “But I guess I can’t say I’m not curious.”

* * *

I googled Nora from my desk. I didn’t have her last name, but she was easy enough to find. There weren’t too many missing Armenian Noras in the L.A. area.

I found a spate of news articles on her disappearance, dating from almost a month earlier. As I read up, the facts started to sound a bit familiar, and I thought I might have heard about this case on the radio. The story hadn’t attracted a lot of national attention, but it wasn’t hidden under any rugs, either. I wondered if it would explode if a corpse showed up.

Her name was Nora Mkrtchian. She was a twenty-five-year-old L.A. native, the daughter of Armenian immigrants who’d left the Soviet Union in the late ‘80s. She ran a Web site called Who Still Talks, a popular niche political blog devoted to discussion of the 1915 Armenian genocide. The L.A. Times called her “a firebrand Internet activist” with a strong following among young Armenian Americans. She’d started Who Still Talks two years ago, when she was a 1L at Loyola Law School in downtown L.A. When she’d generated a following, she dropped out and devoted herself to the blog, posting several times daily while applying to graduate school for genocide studies.

She was last seen on a Friday night in February, when her roommate stated that Nora had appeared “agitated” before leaving the apartment for what was supposed to be only a few hours. Her car was still missing with her, but foul play was suspected.

If the police had any leads, they were evidently not sharing them with the press, but the political blogosphere was abuzz with speculation. Nora had been the target of some serious online harassment. This had been a constant throughout her blogging career, but it had intensified in the months leading up to her disappearance.

I found a link for her Web site and clicked through. It had a simple design, with a few slight embellishments that showed an effort at departure from the standard blogger template. “Who Still Talks” was printed at the top in a thick, crisp-edged font that suggested hip professionalism, millennial savvy, minimal bullshit. Then, in the middle of the page there was Nora, middle finger extended at the top of her last post. I started reading.

Hey guys, today we’re going to talk about me. “But, Nora,” you say to your laptop, “Don’t we always talk about you?” And because I can pretty much hear you, I’ll say: Yes, we do, to an extent. This is my blog house run by my blog rules, and in my blog house, we talk about things that are dear to my heart, and as we all know, I am a raging narcissist. You all know what I care about; my screaming Armenian blood, my conflicted feelings on System of a Down. You all might feel like you know me reasonably well, and you know what? You probably do.

But I don’t talk about some stuff here. I don’t talk about my love life, my family. I could have four kids for all you guys know. (I don’t have four kids.) Believe it or not, I show some restraint. I try not to get too trivial about sharing the day-to-day shit, though you know I #can’t #fucking #resist posting pictures of pancakes from time to time. But honestly, I do think about the things in my life that might help or at least entertain other people, and despite all the random junk that gets through the filter, you guys should know that I do have a filter.

Which is why I didn’t address the harassment till now.

As some of you have noticed, we’ve had a few uninvited guests over the last month or so. I don’t always respond to comments, but I do try and read them all, and I’ve seen you guys engaging these shithead trolls. I want to say thank you to everyone who’s defended me. At first I thought it would be better if we all just ignored them, as a family, but to be honest it felt good to see you guys stick up for me so I just tried my best to stay out of it and let you all do your good work. But it’s gotten to the point where I can’t ignore this shit anymore. These people have gotten so fucking noxious that I’m just gonna go ahead and call them out right here.

Here’s what happened, for those of you who don’t read the comments. (And by the way, I know in general the rule is, Never read the comments, but that hasn’t been true of this site until pretty recently. Most WST readers are respectful, funny, etc. etc. mwah mwah mwah.) Last month, I ran a post on the anti-memorial lawsuit, condemning Thayer White for representing genocide deniers. That got cross-posted on HuffPo, and even now, when you google Thayer White, that post comes up. (Suck it, you soulless mercenary motherfuckers.) Thanks to all that attention, I got a few exuberant new readers, who took it upon themselves to plaster my comments sections in straight-up hate speech. It got ugly and personal really fucking quickly. At first I thought they’d get bored after a while, move on to the next hateable woman on the Internet. That didn’t happen. It got worse and worse, and it’s still escalating. It goes without saying that I get rape threats on the daily. I’ve actually stopped checking my e-mail because some of this comes straight into my in-box. (This is also why I made my e-mail address private a few weeks back, but once you put that shit on the Internet, I guess it stays accessible. Anyone who had it before would still have it, and could share it further.)

I don’t want to go into too much detail, but I will say that I’ve been threatened in a way that extends out of the Internet. It’s been a nightmarish couple of days.

But listen up, you horde of disgusting anonymous cum wads: Enough is enough. I’m coming for you.

The post had been reblogged thousands of times, and there were over eight hundred comments. I checked the dates—the post had gotten a reasonable amount of attention when it was first posted, but it went semi-viral when Nora’s disappearance made headlines. I started reading the comments. Most of them were positive wishes from strangers, praying for her safety.

The comments were unmoderated, with no apparent filter, because a large chunk of them was obvious spam. There were several comments in some version of English somehow both wretched and robotic, gushing about hot dates with older men, and friends who were making hundreds of dollars an hour working from home.

I scrolled through quickly, but one brief comment snagged my attention. It was written in all caps, indicating anger and ignorance, and it said, “I HOPE HE RAPED U FIRST.”

I felt a visceral stab of disgust. The anonymity of the Internet seemed to bring out the worst in people, who were assholes often enough to begin with. I wondered what kind of mask this commenter presented to the outside world.

With sick curiosity, I scanned through the rest of the comments, my eyes alert for more unrestrained hate. I didn’t have to look very hard. About a quarter of the comments were in the same malicious spirit, and it was starting to look like a targeted campaign. There was a lot of name-calling, with particular concern for Nora’s perceived unattractiveness and rampant promiscuity. Some commenters lamented not having the chance to rape her. Others promised to kill her if she happened to turn up alive.

All of these comments were met with condemnation and outpours of support for Nora, if she was reading, from first-time visitors to the site, as well as friends from both the Internet and the real world. The positive voices outnumbered the threats and insults, but even just a few of those remarks would have flavored the pot. As it was, the remarks were far from few, and I suspected there was some sort of organized effort to mob the missing girl’s Web site. I wondered what kind of person would undertake such a project.

I rooted around her archives to get a sense of Nora and her work. She was the sole writer on Who Still Talks, though she interviewed and cross-posted other bloggers regularly. Her posts were frequent, ending abruptly the day of her disappearance. Not every update was serious or even political. The blog had a strong personal bent, with a surprising number of selfies for a Web site with any mainstream credibility. There was also an orange cat that commanded a lot of screen time.

Nora was thin and pretty, with straight, dark hair and large, dark eyes perpetually ringed in black liner and several coats of mascara. She put a lot of evident effort into her appearance. She was in full makeup in almost every picture, and she wore beautiful, expensive-looking clothes, favoring low-cut tops that showed off a rack out of all proportion to the size of her body. There was nothing bashful about this girl.

The Web site wasn’t about her, but its writing and content emitted an easy vanity that was slightly off-putting. It would have been downright obnoxious if it weren’t also pretty insightful. Even the undisguised narcissism had a strain of womanly defiance, some of which was clearly reactive.

Nora’s main focus was on the need for universal recognition of the Armenian genocide, a topic that was still controversial in many parts of the world. She’d started Who Still Talks as a passion project to keep her going in law school, but when she attracted thousands of readers, she decided she’d found her calling. She became a powerful voice for Armenian-American youth, particularly in Southern California.

I felt some embarrassment at how little I knew about the genocide, though it was, apparently, a more obscure topic than I would have thought given the scope of atrocity. Since I was hesitant to get my facts from a blog, even one as established as Nora’s, I decided to go to my number-one source for everything from dog breeds to the lives of serial killers—the often reliable Wikipedia.

* * *

The facts of the genocide made my stomach turn. The death toll was almost inconceivable, as was the pure evil of a regime set on eradicating an entire religious and ethnic minority. The genocide had apparently been the answer to an “Armenian Question”—a question of this Christian minority’s place in early-twentieth-century Turkey. A ruthless answer, one that afforded human life all the respect due to dust bunnies. The genocide was minutely organized and executed with devastating cold-blooded efficacy. The Turkish government even tried to collect on life insurance policies for the Armenians it had exterminated, on the assumption that their heirs were dead, too.

By the time I emerged from this Internet wormhole, it was two o’clock and I hadn’t eaten lunch. I also hadn’t heard from Rubina, so I went for a sandwich and called her on her cell phone.

“Is there something wrong?” she asked.

It struck me that Rubina was a woman who lived in constant expectation of bad news.

“No,” I said. “Sorry, I’m at the office. I’ve just been doing some research.”

“What kind of research?”

I hesitated. “You won’t be charged for my time or anything. I had a slow morning and was waiting to hear from you.”

“Does it relate to me?”

“Sort of,” I said. “I was just reading about Nora, and I found her Web site.”

“Oh.” There was a startled flutter to her tone. “We are all terribly worried about her.”

“Do you know where the police are on her disappearance?”

“I don’t know much more than what’s in the papers,” she said neutrally. “Are you very interested?”

I bit my lip. “I’m concerned,” I said. “It seems like she has a lot of enemies.”

“Yes, she does. She’s an attention-seeker and a rabble-rouser. It’s only natural that some people don’t take to her.”

“Do you think she’s”—I paused, looking for the most delicate word—”alive?”

“I don’t know. I’d like to think so, but she has been missing for a long time.”

“Do you know that she was the victim of an online harassment campaign? These—”

“I know about that,” she interrupted. “You’re beginning to sound a bit like Lusig.”

I colored at the admonishment. “I’m sorry. It’s hard not to be interested in this kind of thing.”

“That’s okay, but let’s keep things clear. Whatever happened to Nora has no bearing on me or my baby unless Lusig lets it claim her. I’ve hired you so I can make sure that doesn’t happen. That’s all. Do we understand each other?”

“You mean, do I understand you.”

“Excuse me?”

“You asked if we understood each other, but I haven’t asked you for anything. If you’re going to reprimand me, just reprimand me. No need for the royal ‘we.’”

“I’m sorry. I’ve been told I can be condescending, but that is not my intention.”

“No problem,” I said. “And yes, of course I understand. I am committed to your case, and I won’t do anything that could impair my ability to work for you.”

“Thank you.”

“So what’s next?”

“I’m concerned about her behavior last night. I want to know if it’s part of a broader pattern. Is there a way that I can put Lusig under full surveillance?”

“Depends what you mean by ‘full.’ Are we talking 24/7, Big Brother Is Always Watching You surveillance?”

She forced a small laugh. “Is that available?”

“No,” I said. “We don’t have God powers.”

“What is available?”

“I can keep a steady tail on her within reasonable bounds. I need to sleep, eat—well you’re a doctor, so you know these things.”

“Can I hire two of you?”

“We’re a small outfit, just three investigators. I can ask Mr. Lindley and Mr. Flores to fill in some gaps, but I think it would be hard to keep two of us on this one case at all times. That being said, I won’t hold it against you if you want to reach out to a bigger outfit. Obviously, anything you’ve told me I keep in confidence, and that goes for the fact that you even walked into my office.”

“No,” she said quickly. “Believe it or not, it was difficult for me to talk to you in the first place. I’d rather proceed with whatever you can provide, as long as that’s moderately comprehensive.”

“Of course. If you want, I can even see about getting a GPS tracker on her car.”

“That won’t be necessary.”

I could tell by her breathing that she had something to add. “It won’t?” I prompted.

“I’ve already attached one.”

“Oh.” I laughed. “You’re prepared. Are you sure you even need me?”

“I don’t care particularly where she goes. It’s what she’s doing that concerns me.”

”It sounds like you haven’t bugged her phone or apartment. I wonder what’s stopping you.”

I must have sounded snider than intended, because she dropped her voice to a quiet, sheepish tenor. “You must think I’m mentally unstable,” she said.

“No, sorry, not at all. Didn’t mean for it to come across like that.”

It was true enough that I thought she was extreme, but I’d never had a client who wasn’t a bit more willing to indulge paranoia than the average goon on the street. In any case, I took their money and let them use me to probe, invade, spy, whatever. Their paranoia was my cash cow.

“It’s very important to me that Lusig take care of her body. I cannot have her acting out where I can’t see her. It won’t do.” She sighed. “However, there are certain barriers I can’t cross—that is, not directly.”

“Are you worried that Lusig would find out?”

“Yes, there is always that chance, though I try not to worry excessively about things that might never happen.” She paused, perhaps catching the irony. “But even if I knew Lusig would never find out, I would feel guilty and uncomfortable about spying on her with my own eyes and ears.”

“Which is why you contacted a mercenary.” I smiled. I’d spent years romanticizing the literary private detective, but now I wore the badge, and I knew more or less what I was.

“Yes. Do you understand my position? I think all this is quite necessary, but I have no intention of betraying Lusig’s trust where I can avoid doing so. If you overhear her talking about me, or my husband, for example, you don’t have to tell us that. I only need information pertaining to her obligation to me.”

“Sure.”

“Song,” she said, pronouncing it slowly.”Is that a Korean name?”

“Yeah. So is Juniper.”

“Oh, how so?”

“Sorry, I was kidding. Though I guess only an immigrant would name her kid that. Anyway, what about it?”

“I don’t know how things are in your culture, but Armenians are very family-oriented.”

“Koreans, too.” I didn’t mention that my own family was all but entirely disintegrated.

“Of course, no one would describe her culture as non-family-oriented, but the standard American model is to put the individual first, and that is not the case for Armenians. Do you know what I mean?”

“Yeah, it’s an immigrant thing.”

“Yes, exactly. In our family, at least, the lines that divide us are very fluid. And within our family? Lusig and I are bonded as strong as sisters.”

I knew the feeling of being lied to by a sister, of wanting to know when I wasn’t being told.

“Now, add to that that Lusig and I are both mothers to the same child. I feel that she would forgive me a decent level of intrusion.” She paused, and when I didn’t insert my agreement, continued. “Not that I need to defend myself, of course. I just don’t like to be thought of as unpleasant.”

“Don’t worry, Rubina. I don’t judge my clients.”

This wasn’t strictly true—most of my clients weren’t great people, and I was generally aware of their various flaws. It was part of my job to account for them, after all. But one thing Philip Marlowe and Sam Spade let you forget was that private investigation was a service job. The renegade PI was an interesting figure, but it was no accident that Marlowe never made any money. I was beholden to my clients, not just for services rendered, but for a baseline level of courtesy. I wasn’t obsequious, but I was too old to take pride in being an asshole.

So while I couldn’t avoid forming general impressions on my clients, I maintained a fiction of impartiality, like the kindergarten teacher who loves all her students equally. My judgments were compartmentalized to the point where they couldn’t offend.

“The GPS tracker, have you been using it?”

“Lightly,” she said. “I was thinking it would be a good supplement to your service.”

“Is it a real-time tracker?”

“Yes.”

“Do you want to give me access to that?”

“That would be fine.”

“Alternatively, we can use the tracker to cut down on my hours. Not that I wouldn’t love to bill you for time spent reading a novel outside of her apartment, but maybe you don’t want to pay me when I’m not going to see anything.”

She was silent for a few seconds, and I worried she thought I was being lazy.

“I guess that isn’t exactly 24/7,” I said. “But think about it. She’s not trying to sneak around. I don’t think she’ll be beating on your baby when she’s alone in her apartment.”

“Yes, you’re probably right. I suppose I was overzealous.”

“How about this? We can start with some spot surveillance. If she’s going anywhere of interest, I’ll make sure to follow. Where does she live, by the way?”

“Koreatown.”

“Close to the office,” I said. “Ah, is that why you picked us?”

“That is how I found you, yes.”

“Convenient for me.”

She gave me an address and detailed notes about Lusig’s schedule, like an anxious parent instructing a new sitter. I was glad I wouldn’t have to change any diapers.

We hung up with the understanding that I’d check in at regular intervals, and I went back into my idle Internet research, just in case.

Copyright © 2015 Steph Cha.

To learn more or order a copy, visit:

Steph Cha is the author of Follow Her Home and Beware Beware. Her writing has appeared in The L.A. Times, The L.A. Review of Books, and Trop Magazine. A graduate of Stanford University and Yale Law School, she lives in her native city of Los Angeles, California. Dead Soon Enough is her third novel.