Criminal Clergy: Depictions of Religion in 1950’s Film Noir

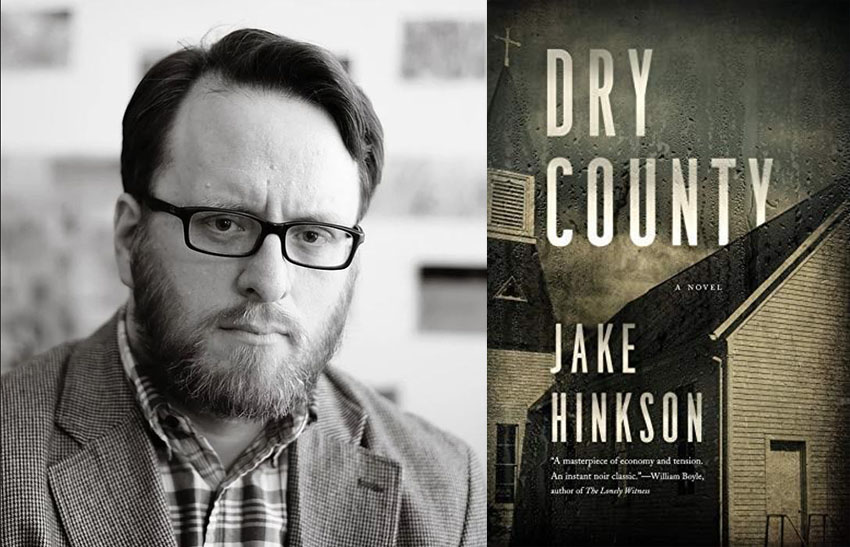

By Jake Hinkson

October 2, 2019

The brilliant 1950 noir The Sound of Fury begins with a blind street preacher warning passersby that “Whatsoever a man soweth, that shall he also reap.” If you think about it, this verse from the Apostle Paul’s letter to the Galatians could work as an epigraph for all of film noir. It certainly works to set up The Sound of Fury, a film that tells the story of the downfall of a struggling family man named Howard Tyler (Frank Lovejoy). One day Howard meets a hood named Jerry Slocum (Lloyd Bridges) who offers him a job as a getaway driver for a string of robberies. At first Howard says no, but when he thinks it over and finally accepts Jerry’s offer, you can smell the sulfur burning. After Jerry upgrades their criminal enterprise to kidnapping and murder, the film becomes a slow-boiling nightmare fueled by Howard’s deepening guilt. “I keep thinking God is coming after me,” he tells his wife. The Sound of Fury, inspired by true events, was written by novelist Jo Pagano as an indictment of lynch mobs and journalistic cravenness, but the power of its narrative comes from the way it marries Howard’s downfall to the street preacher’s warning about sin and its terrible consequences.

That warning reverberates throughout film noir. Noir City might be one godless little town, a place of perpetual night, populated by men and women bleary-eyed with booze and bad judgment, but underneath the tales of lust and larceny, there beats a moralistic heart. After all, most noir boils down to the preacher’s warning: you pay for your sins.

What makes this doubly interesting, however, is that noir rarely affords us a positive view of the clergy. The men of god we find in Noir City are of a piece with the town’s other denizens: they’re weak, wicked, or both. In noir, everybody’s a sinner, and everybody is going to hell. That includes god’s mouthpieces. In fact, they might be the biggest sinners of all.

In Mark Robson’s little-seen 1950 Edge of Doom a young man named Martin Lynn (Farley Granger) develops a grudge against the church when his parish priest refuses to bury Lynn’s father after he’s committed suicide. Later, when Lynn’s mother dies, he confronts the elderly priest to demand a fancy funeral for her. The indignant priest refuses, and Lynn kills him in a rage.

The above description should come as a shock to anyone familiar with movies of the time. Mainstream Hollywood movies in 1950 simply didn’t feature unsympathetic clergymen. They didn’t show young men who were angry with the church for anything. Religion in those days was a protected institution, especially during the time of the Red Scare, and the sinful denizens of Hollywood were all too happy to portray any and all religious authorities as unquestionably good. In most Hollywood films of the forties and fifties, God existed and he was an American.

Edge of Doom is a fascinating film because it shows the first strains in this façade. The movie still has to make several concessions to the production code (Dana Andrews plays a good priest trying to help Granger, and the church is, of course, ultimately absolved of any wrongdoing), but for most of its playing time it is a tough look at religion. The priest murdered by Granger may not be the pedophilic monster of today’s headlines, but he is dogmatic, unforgiving, and entitled. We’re shocked to see him murdered, but we’re more shocked to see him portrayed as a self-righteous old fool hiding behind his collar. While he does not deserve to die, his murder flows out of Granger’s understandable anger at him. In other words, we in the audience are asked to identify with the murderer of a priest. And, damn it all, we do.

Of course, the old Catholic priest can’t hold a church candle to the crazy Protestants. Lewis R. Foster tough-as-nails 1955 jailbreak flick Crashout gives us a motley group of escaped convicts on the run from the cops. Among their number is the always great William Talman (The Hitch-Hiker), in one of his best parts, as a knife-throwing Jesus freak named Luther Remsen AKA “Reverend Remington” who is in jail for the “celebrated soul-saving murder” of a church organist.

The film seems to answer this question by giving us what might be the most grotesque religious ritual in all noir when Reverend Remington baptizes a wounded man in a muddy drainage pool and tries to drown the guy in the process.

Crashout is no masterpiece—it starts to drift toward incomprehensibility in the closing scenes—but it is a deeply subversive piece of work. Star Arthur Kennedy is given a speech that pretty much sums up the noir ethos: “There’s no road back. There’re no yesterdays. There’s no tomorrow. There’s only today. Every day you live is a day before you die.” With this in mind, how much sense could one make of the promise of life everlasting? Especially when the only preacher on hand is crazy Reverend Remington? The film seems to answer this question by giving us what might be the most grotesque religious ritual in all noir when Reverend Remington baptizes a wounded man in a muddy drainage pool and tries to drown the guy in the process. The moment is still shocking. Crashout perverts Protestant Christianity’s most sacred ritual—the immersion baptism which symbolizes the believer’s death and resurrection in Christ—into a wickedly profane murder attempt.

In 1950, the character of Reverend Remington reflected a deep skepticism of new mass-media-mongering evangelists like Will Stidger and J. Frank Norris, Bible-thumpers given to greed, hedonism, or violence (Stidger inspired Elmer Gantry, and Norris once shot a man dead in his own church). New technologies, and shifts in political fortunes, were pushing religious snake-oil salesmen into the media spotlight. Someone like Billy Graham—of whom Harry S Truman disdainfully said “All he’s interested in is getting his name in the paper”—might have matured into a statesman and winner of the Presidential Medal of Freedom, but to a great many people in the fifties, the pulpit-pounders still seemed like charismatic phonies.

Of course, this suspicion found its clearest expression in the most notorious clergyman in all noir: the Reverend Harry Powell (Robert Mitchum), the woman-murdering preacher who occupies the center of Charles Laughton’s The Night of the Hunter. With HATE tattooed on one hand and LOVE on the other, the slick-talking Powell is like a Flannery O’Connor character wandering a weird landscape of bucolic Expressionism. His tattooed knuckles and his parable of the “story of good and evil” are symbols foreshadowing his ultimate showdown with a shotgun-and-Bible wielding old lady named Rachel Cooper (Lillian Gish).

Though The Night of the Hunter is a blistering portrayal of religious authority, it is certainly not a condemnation of belief itself. As the film’s producer Paul Gregory later told Preston Neal Jones, author of Heaven and Hell to Play With: The Filming of The Night of the Hunter, Laughton felt that adapting Davis Grubb’s excellent novel “was a marvelous opportunity to show that God’s glory was really in the little old farm woman, and not in the Bible-totin’ son of a bitch.”

It says something about noir’s view of organized religion that Harry Powell is its most notable representative. Powered by Mitchum’s mesmerizing turn, Powell embodies every criticism ever leveled at American Christianity: greed, hypocrisy, misogyny, murderous self-righteousness. Of course, at the time of its release, the film was controversial in some corners for its depiction of the killer preacher, but it was mostly shunned, disappearing from public view, kept alive only by cinephiles and crime fans. That it has survived and flourished to the point that it is now widely considered a classic, is a testament not only to Laughton and his cast and crew, but to the enduring power of film noir’s uniquely subversive critique of religion.

*Author photo credit Michelle Graves

About Dry County by Jake Hinkson:

A dark vision of American religion and politics, Dry County is a portrait of a man willing to do anything to hold on to his power―including murder.

Richard Weatherford is a successful small-town preacher in the Arkansas Ozarks. He’s a proud husband and father of five, and has worked hard to grow his loyal flock with strong sermons and smart community outreach. But while Weatherford is a man of influence and power―including a big force in local politics―he’s also a man with secrets.

In the lead up to the 2016 presidential election, Weatherford’s world is threatened when he’s blackmailed by a former lover. Collecting the money the blackmailer demands will be a nearly impossible feat, especially over Easter weekend, when all eyes are on him. So Weatherford will have to turn to the darkest corners of their small town in a desperate attempt to keep his world from falling apart.

Exploring a divided country and a cracked façade through the alternating perspectives of Weatherford, his wife, his lover, and other town residents, Dry County is a powerful story about how far some will go to keep hold of all they know―and all that others think them to be.

Comments are closed.

Very telling article on noir in the Fifties. Well done.

Clearly a theme that spills over in Jake’s novels. Fascinating for anyone especially for non-Americans unfamiliar with Christianity in the Southern states.