What is the story told between the lines of crime fiction? More than a genre with deep literary histories in many cultures, it is a mirror of how law, politics, and society are perceived. Be it procedural, cozy, or noir, it often deals with injustices faced by the marginalized, the displaced, the underdogs.

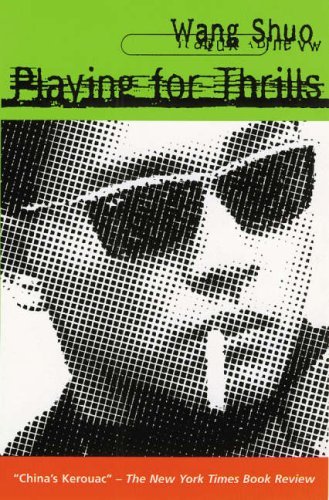

Set in the seedy underside of Beijing, the story revolves on a rogue main character’s attempts to ascertain whether he really committed the murder he was accused of 10 years ago. The thematic elements explored are the decay of Communist revolutionary ideals, mass market liberalization, hyper-materialism, and disenfranchised youth stratified in a turbulent, morally bereft society.

Despite the fact that Chinese crime fiction has gained popularity in the West, Chinese writer Murong Xuecun, at a recent gala in Melbourne Town Hall, commented on why crime fiction written about China doesn’t pay in China. Though the Chinese government has significantly relaxed standards in recent years, conventions and tropes in crime fiction are still rigidly limited.

Censorship issues in China highlight the difference between ‘law in literature’ and ‘law as literature.’ All forms of media (television, film, press, etc.) are subject to approval by the State. Deviations from politically correct beliefs and ethics are labeled “dangerous.” Of course, in turn, there is a huge black market for Hong Kong gangster cult films and similarly for hardboiled fiction.

After all, censorship is a double-edged switchblade.

Fascinating. I’ll put it on my reading list for sure. Thanks.

This looks so up my alley. Thanks for pointing it out, putting on the wishlist.

I [u]highly[/u] recommend Wong Kar-wai’s thriller romance Fallen Angels for a film experience of “hooligan literature.” One of my favorite movies of all times. Here’s a scene from the film to [url=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OQN6Gkv4JRU&feature=related]get a taste[/url].

I’ve seen Fallen Angels! Takeshi Kaneshiro is one of my favorite actors, and I really like Wong Kar-wai, too (In the Mood For Love is gorgeous).

Sounds great! I think you can make an argument that noir lit is inherently subversive because it combines a sense of futility and an automatic suspicion of authority. Modern-day China sounds like a good place for it.

Where can I find this movie to watch???

@Jake. I cannot agree more. It’s always fascinating to me the ingeniously irreverent ways Chinese writers (and netizens) find to exploit loopholes in censorship. Unfortunately, much of the literary play on words is lost in translation.

@Edgar. It’s available on Netflix and for sale on Amazon. If you don’t mind compromising video quality, it’s also available in its entirety on YouTube. Here’s the link for [url=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NCFFJbREVN0]part 1/10[/url].

I’ve seen it. Fantastic movie!

Thanks! C.Z.