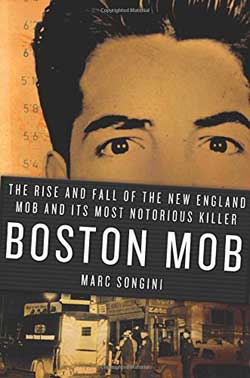

Boston Mob: The Rise and Fall of the New England Mob and its Notorious Killer by Marc Songini is a true account of the historically violent Boston mafia and its reign of terror (available July 29, 2014).

Boston Mob: The Rise and Fall of the New England Mob and its Notorious Killer by Marc Songini is a true account of the historically violent Boston mafia and its reign of terror (available July 29, 2014).

The New England Mafia was a hugely powerful organization that survived by using violence to ruthlessly crush anyone that threatened it, or its lucrative gambling, loansharking, bootlegging and other enterprises. Psychopathic strongman Joseph “The Animal” Barboza was one of the most feared mob enforcers of all time, killing as many as thirty people for business and pleasure.

From information based on newly declassified documents and the use of underworld sources, Boston Mob spans the gutters and alleyways of East Boston, Providence and Charlestown to the halls of Congress in Washington D.C. and Boston’s Beacon Hill. Its players include governors and mayors, and the Mafia Commission of New York City. From the tragic legacy of the Kennedy family to the Winter Hill-Charlestown feud, the fall of the New England Mafia and the rise of Whitey Bulger.

Chapter 1

THE PORTUGEE FROM NEW BEDFORD

“In New Bedford, fathers, they say, give whales for dowers to their daughters, and portion off their nieces with a few porpoises a-piece.”

—Herman Melville, Moby-Dick

On September 20, 1932, was born the infant destined to mutate into “one of the worst men on the face of the earth.” Joseph Barboza Jr. spent his first years in the small coastal city of New Bedford. This once-legendary former whaling port nestled on a North Atlantic peninsula. But Joe had selected an inopportune time to join this city’s oppressed and hard-toiling population. Eight decades before his arrival, the city was “perhaps the dearest place to live in, in all New England,” Herman Melville claimed. “It is a land of oil, true enough: but not like Canaan; a land, also, of corn and wine … nowhere in all America will you find more patrician-like houses; parks and gardens more opulent, than in New Bedford.”

Had Joe been born a hundred years prior, his savagery and viciousness would hardly have drawn attention in a whaleship’s forecastle. There had been legal opportunities back then for fierce, bold men like him. However, before Joe arrived, the whalers’ staple game, the sperm and bowhead leviathans, grew very scarce. The Civil War and a run of Arctic disasters pared down New Bedford’s once-famous whaling fleet. In 1924, New Bedford’s last whaler of note, the Wanderer, had smashed into the shallows off Cuttyhunk Island during a gale. That had clearly marked the death and burial of Yankee whaling.

By the 1930s, New Bedford’s smart money had relocated into unheroic and unglamorous industries, such as textiles or railroads. Graceful ships’ masts went out; smokestacks replaced them. With muscle, blood, spindles, smoke, grime, and decaying grandeur to sustain it, New Bedford persisted in a second (or third) life. Its ugly factories crowded the skyline, and its dirty and overflowing tenements competed for space with the fine houses, banks, shipyards, and church spires of a prior era. In short, the onetime “City of Light” was like any other New England factory metropolis on the slide down.

At the time of Joe’s birth, the white leviathan sinking New Bedford was the Depression. In 1932, a local textile baron kindly loaned a desperate New Bedford $100,000 so it could make its payroll. But this was akin to applying a bandage to an incurable sore. Needless to say, a New Bedford working family’s life was then very harsh, only slightly better than a slave’s. Factory wages barely sustained life, and malnutrition and poverty killed off more children in New Bedford than in almost any other U.S. city. A favored child learned the useful skill of weaving from a parent, without pay. Hopefully, the apprentice lasted until age fourteen, when he started working legally and repaying the investment made in him.

The second Barboza child, Joe was about as isolated as one can get. In tiny compartmentalized New Bedford, the Portuguese managed to stand apart, clannish, with a separate tongue and unique flavor of Roman Catholicism. In that little hardscrabble community, Joseph Barboza Sr. managed an uneasy truce with his wife, Palmeda “Patty” Camile, with whom, for a while, he raised five children. Barboza eked out a subsistence living, and sometimes less, as a milkman and factory worker. For cash, he also boxed, proving “one of the best little 160-pounders” from the region. But Barboza was also a convicted petty criminal, with a taste for women and drink, and not exactly monogamous. He was also a wifebeater, and once scattered Patty’s front teeth with a blow.

In the long-suffering manner of the time, Patty pretended he was faithful. But the domestic misery was as contagious as measles. “The house we lived in was more of sorrow than of happiness,” as Joe later noted. “We were constantly on welfare.” One day, Joe came home and found his mother unconscious, with the gas jet on. Patty survived, but her mate abandoned the family completely.

Once, Patty ordered Joe to beg for his father to return home. While Patty waited on the street, the boy found Joseph Sr. outside in a yard with a woman he’d “shacked up” with.

“Get out of here, you little bastard,” his father said.

“The punk broke my heart,” the future career criminal admitted. Crying, Joe turned and ran down the street to his mother. Having a change of heart, Joseph Sr. drove after him and found him with his mother.

“He will never forget this,” Patty told her husband. Joe wept all the way home. Although Barboza bought Joe a pigeon, he didn’t return to the family flat.

Minus the family breadwinner, Patty also worked as a waitress and even shoplifted, for which she was arrested. Shunned by her husband, for solace, Patty clung to Joe and his brother—who were then running “wild.” Joe felt she used him as bait to keep something, any little bit, of her husband.

Joe never forgot his extreme poverty, nor how his mother had suffered through it. This unhappy childhood packed him with enough explosive rage for a lifetime. Aware he was a shuttlecock between his parents, Joe took to freely roaming the streets with other urchins. There, as he put it, “I had a better type of love.” And if his father ignored him, at least he could command the attention of New Bedford. Thus, Joe drifted steadily into wild waters. He started smoking at age seven; at fourteen, police arrested him, apparently for damaging an electronic streetcar signal.

Lacking a stable family at home, Joe created another type of family by forming a gang. Joe’s criminal apprenticeship moved from shoplifting to burglary. During the day, Joe’s crew would go window-shopping, and then return later to steal whatever items the members had coveted. In 1945, the police arrested Joe for breaking and entering, and at age fourteen, Joe graduated to the Lyman Reform School, a “hellhole” of constant brutality. Orderlies beat Joe and the other residents with belts and pick handles. But the house specialty on the pain menu was the “hot foot,” where orderlies struck the naked arch. To survive, Joe made himself the brawling champion of Lyman, getting into three hundred fights.

When released, he began to box in the ring.

“He was tough and strong,” noted a New Bedford boxing fan, “a real crowd pleaser who could take an opponent out with one punch—if he could hit him.” Few boxers wanted to mix with Joe, who was all attack without much defense. In one notable fight in a Boston arena, a lanky black middleweight knocked Joe down twice, but won by decision. “Actually, it was a hell of a fight; the guy beat Barboza only because he was the better sharpshooter and made his punches count,” a fan recalled years later. Against very good fighters, Joe had little chance at all. The incarcerated boxing great (and fellow psychopath) Bobby Quinn sparred in jail with young Joe. “I used to beat him till my hands hurt,” he recalled.

* * *

The state tried again to rehabilitate Joe, this time by sending him to a vocational school. After a woodworking teacher insulted him, Joe rallied his gang to trash the classroom at night. Newspapers claimed someone had hurled a pie at a wall, and a writer dubbed the crew the “Cream Pie Bandits.” With the seventeen-year-old South End resident as their leader, the bandits allegedly broke into two hundred cars in six months. In December 1949, the gang launched a veritable petty reign of terror, entering unoccupied houses, restaurants, businessess, and cars and stealing anything it could spend, enjoy, or sell. The takes generally didn’t top ten or twenty dollars apiece, and the goods included a necklace, socks, cigarettes, lighters, caulking tools, and, possibly, even Christmas trees. Before New Year’s Day, police arrested Joe, the ringleader, and another thief. In court without counsel, Joe and his colleague, the only two bandits of adult age, pled guilty to all counts.

To mark Joe’s holiday season, a judge sentenced him to five years and a day in the Massachusetts Reformatory in Concord. This cut short his formal education at grade eight and put his fight career on hold. Concord existed to reform juvenile delinquents. Its record was reliable: 80 percent of its graduates committed more crimes. There, in the town of the prophets of freedom, Thoreau and Emerson, Joe worked as a penal slave in a weaving mill. Later, he graduated to the dining room, where he remained—until, during a brawl, he broke an older inmate’s jaw in two places with a left hook. For that, Joe went to solitary, then to the boiler room to shovel coal and stoke an ever-growing rage. “Being a convict sure is a lowly state & they don’t let you forget it!” as he once observed.

* * *

In January 1951, Joe transferred to the relatively bucolic Norfolk County Prison, which functioned like a rehabilitation center. There, he boxed as a middleweight, knocking older men out routinely, he later boasted. Such a good thing couldn’t last, and in September 1951, high on paint thinner, he challenged the guards to come and get him. After a two-hour stalemate, no longer intoxicated, Joe negotiated peace terms. This finalized the nineteen-year-old Animal’s contract in life. The authorities (presciently) determined him beyond rehabilitation. Back to Concord Joe went.

Now Joe joined with a ring of enterprising guards, who, for a premium, did business with the inmates, and even took their bets. Their commodities included steaks and other fine food and drugs, including “goofballs,” or tranquilizers, and Benzedrine (“bennies”). Working on his undergraduate’s degree in criminal science, Joe apprenticed with a wayward “screw” or guard, who demonstrated the tricks of smuggling. The enterprising Joe began dealing in bennies, liquor, knives, and food with other inmates.

The warden, sensing Joe might be a good leader of bad men, offered him the chance to work the prison farm—if he behaved. Joe repaid this trust by leading a prison riot, and back to solitary (and bread and water) he went. Later, finally allowed back on the farm, Joe enjoyed something like an idyllic life. He drove a team of horses, which he “dug”; surreptitiously swam in the nearby reservoir; and watched TV nightly. From the prison henhouse, he stole chickens for a fellow convict to fry.

Joe had just cracked the second decade of his life when his personality set. He was pretty much—mentally, morally, and physically—the man he’d remain as an adult. As he grew, something in his genetic code misfired, aesthetically and morally, at least. Once, he’d been a slender and clean-cut teenager. But during his jail years, he metamorphosed into a grotesque caveman. He topped off at maybe five feet ten inches, a distance containing a massive torso that included a forty-six-inch chest and thirty-five-inch waist. But the legs remained relatively short and stubby, and didn’t quite appear to fit symmetrically with the upper body they supported.

The burly Joe weighed 185 pounds, and his big padded hands were matched by feet that required a size-ten shoe. A mole dotted his right cheek above the massive jaw, while over his small sleepy brown eyes, long eyebrows fluttered. His profile was almost a flat vertical line from his forehead to the jutting Hapsburg-sized chin. He had JOE tattooed on his right forearm, and BORN TO LOSE and 1932 (his birth year) on the right biceps. A pair of boxing gloves and a scar adorned the left biceps. To perfect the appearance, he carried himself with a swagger. As one knowing reporter claimed, “he could have passed for just another cheap punk who hung out on New Bedford street corners and picked up a buck here or there running numbers.”

As far as morals, he believed all men will do whatever they want until they are caught violating the law. Therefore, Joe formed a compromise with himself—publicly, he’d appear to be good, while privately, he’d break the rules. And he was often caught. He made the headlines at age twenty-one, when drunk on Concord home brew and goofballs, he led a seven-man escape. His makeshift gang beat several guards, and took one of their cars—an ancient and unreliable machine that died in the middle of Route 27. Joe and four companions reached a nearby gas station, which they robbed. While stealing a car, Joe hit its owner hard enough to fracture his cheekbone, and nearly blinded him in one eye. The crude escape made page 1, and the law sought the fugitives everywhere in New England. Instead of hiding, on July 14, Joe and two other escapees visited a Revere Beach barroom before boarding a bus to East Boston. During a stop at the busy Orient Heights MTA station, three policemen, their guns drawn, boarded the bus. After Joe and his cohorts surrendered peaceably, the police showed them off like landed prize fish, posing the manacled trio for a news photographer.

Back in Concord, Joe visited solitary, exchanging choice words with a guard before striking him with a table. Six more guards descended on Joe to hogtie him. They then hustled him into a dungeon for ten days to live on bread and water. Despite promises of light punishment, he refused to squeal on the ring of corrupt screws he’d partnered with. Sometimes, during his solitary stretches, he staged conversations with himself to avoid going completely crazy.

* * *

In May 1954, Joe’s Revere vacation resulted in a decade-plus sentence in Charlestown State Prison. The “gray monster” was little more than a series of huge granite slab walls that encased the state’s worst men. Dust from the nearby railroad coal yards perpetually covered its surfaces. The cells had no running water, so an inmate defecated in a bucket in his cell. The facility did have one touch of modernity: the state’s electricity-powered murder seat. A convict on his way to do time here could briefly catch a glimpse of the Bunker Hill obelisk and the masts of the U.S.S. Constitution. Then, he passed through the gates and joined his new family, which included the hardest killers, thieves, rapists, and psychopaths in the Commonwealth. For the infraction of not smiling at a guard, a convict could do solitary—which meant pitch blackness on bread and water. Yet by 1955, at age twenty-two, ever the leader of bad men, Joe headed the inmate council at the “ancient Bastille.”

Perhaps sensing leadership potential, the authorities tried to decipher this wayward Bay State ward. In 1956, one doctor noted Joe’s “features make him look less bright than he actually is; his I.Q. is of the order of 90–100 and he has the intellectual ability to do well in a moderately skilled occupation.” But a later report noted Joe’s “sociopathic personality disturbance” and concluded there was “always a great possibility of further anti social behavior in the future.”

Chapter 2

AN ANIMAL IS BORN

“Bubbles, you can believe I never bow to anyone! Never have all my life! Gone to some nightmares … to never bow down.…”

—Joe Barboza, in a letter

A new home soon beckoned to the budding Animal. In 1955, Walpole Prison opened its gates as the new Harvard University of the criminal class of Massachusetts. Nine million dollars had bought a chalk-white alien-looking rectangle containing a jail, administrative building, and ball field. Twenty-foot walls bristling with coils of razor wire connected the eight outer towers. Anything beyond that would fry on the electric fence surrounding the facility.

“In the joint [Walpole] you live in a space a little bigger than your average closet,” said the North End thief Willie Fopiano. “And you sleep just a few feet from your toilet. After lights out, a guard beams a flashlight on you every hour. If he doesn’t see some flesh in the bed, he opens the cell and shakes you awake. If that happens too many times they haul you off to solitary. Every day you’re ordered around, by shouts of guards or squawks of loudspeakers. It takes a long time to adjust to all that.”

Frequently in solitary but needing to communicate, young Joe learned to write poetry as a diversion—and possibly to maintain a dialogue with himself. A jailhouse Walt Whitman, his earnestness almost compensated for a lack of style. In his poem, “City of Forgotten Men,” Joe portrayed himself as one of 500 men locked inside “dark gray stone.” The years were coming and going, and they were all creating dreams in the sky.

“We only pray that we never again

Return to the city of forgotten men.”

That same year, 1958, Joe at last made parole. Leaving Walpole, in July he married Philomena, a “fine, fine” East Boston divorcée and mother of four. She was sixteen years his senior—but with her, Joe had enjoyed an eight-years-long letter romance. For money, he briefly worked the fish pier and the ring—but, by September, a failed break-in returned Joe to the ever-waiting Walpole.

Back inside, one “weasel” of a kitchen worker annoyed Joe enough to merit a sucker punch. Joe laid the man out cold, so that he required a spinal tap. The warden then exiled Joe from the kitchen to work outside. This helped Joe relaunch his various lending and gaming enterprises. Soon, he’d assembled a bankroll worth hundreds to buy food through a screw.

He ventured into the surrounding woods for meetings, and sometimes donned a sports coat and drove to restaurants. He swam or fished, bred rabbits, and indulged in what eventually became his lifelong passion for cooking. In 1960, with the help of his boxing manager, Joe again made parole. Before he left Walpole, Joe handed his bookmaking and shylocking operations to Vincent James Flemmi—always just “the Bear” to Joe—and other favored convicts.

Once out, for reasons unclear, he also filed divorce papers against Philomena. She didn’t contest them and died a few years later of a “bad heart,” as Joe said. Focusing on his career, Joe reentered the ring—a boxing magazine featured him as a prominent up-and-coming fighter. For a day job, his boxing manager hired Joe for his scooter-rental agency in Park Plaza in downtown Boston. The manager also fronted him money, with which to breed money, in the process known as shylocking. His first year, Joe took the initial $2,000 and turned it into $25,000, becoming one of loan-sharking’s “lesser lights,” as the FBI put it. Those that didn’t repay their loans faced punishment, which even Joe admitted could be excessively harsh. He warned people not to take loans they couldn’t repay. Joe explained to one client (whose face he’d sliced open) that he didn’t get his “jollies” from hurting people. This victim agreed he’d caused the stabbing.

Joe noted: “I was glad he said it because when I hurt a customer I always wanted to make sure it was their fault.” However, having a victim out on the street displaying a scarred face and neck was like buying an advertisement. But, violence had limits, even to Joe. As he said, amused, “If anybody died from shylocking, it’d be a $90 dollar customer—it won’t be the $5,000 customer, because that [murder] don’t get you your money back.”

Although born a Portuguese Catholic, Joe so freely associated with the Sons of Abraham he became known as the “King of the Jews.” Joe boasted about his Jewish brawling buddies at Nantasket Beach, where, on weekends, he bounced in Duffy’s Lounge. Being from New Bedford, he enjoyed gazing out at the open spaces of the ocean after leaving jail. After beating up some of the local rowdies, he was able to enjoy the job in peace. (He did, however, clock a police chief’s son, which required a cash remedy.) Friends arranged for Joe to receive a driver’s license and an unreliable 1952 Dodge. One day, when the car died, ex-con and loanshark Gaetano “Guy” Frizzi tinkered with the engine till it started. Later, the two men drank coffee and, eventually, started a partnership—with Joe providing muscle to Guy and his two brothers, Conno and Ninni.

Joe and Guy formed an odd and vastly antisocial pair. Joe claimed Guy mimicked the gangster-actor George Raft—and was foulmouthed, obnoxious, and violent. In short, he was rather like Joe. However, Guy slapped women around—which soured Joe. Nevertheless, within two years, $5,500 was rolling in weekly “by way of interest,” and Joe’s bank rose to about $70,000. To handle the action, he and Guy took on four other associates, including one promising thug named Carlton Eaton.

Alone, Joe was maniac enough, but coupled with his henchmen, he was a loaded pistol without a safety. In a Revere restaurant, Guy once started a fight with a Malden bookmaker’s bodyguard. Joe ended the altercation by first stabbing the tough with a broken bottle, then knocking him out with two punches. Soon after, one of Barboza’s crew stabbed an off-duty Boston policeman at the Peppermint Lounge. Joe and Guy might have been arrested if the wounded officer hadn’t been committing adultery the night of the fight. Later, Joe claimed Guy had started a curse. As for Guy, he soon realized that Joe was more than a partner—he was a menace, even to his friends.

To learn more about, or order a copy, visit:

Marc Songini is a Boston-area journalist whose work has appeared in the Boston Herald, the Boston Globe and numerous other major publications. He is also the acclaimed author of The Lost Fleet, a chronicle of Yankee whaling and disaster at sea.

This sound like a new type of mobster book I might like to read.

The roof is literally at the top of any homeowner’s maintenance list, and they’re subject to lots of wear and tear.