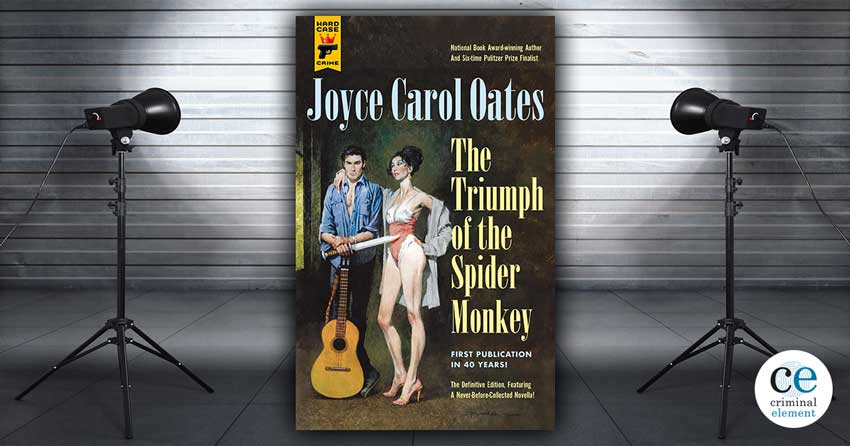

Book Review: The Triumph of the Spider Monkey by Joyce Carol Oates

By Thomas Pluck

July 15, 2019

Unavailable for 40 years, The Triumph of the Spider Monkey by Joyce Carol Oates is an eloquent, terrifying, heartbreaking exploration of madness, which pairs the original novel with a never-before-collected companion novella.

Yes, they loved him. He was never to blame. They cringed and writhed for him, they squealed, pressed themselves against him accidentally in crowds at Venice Park or in big jumbled weekend streams of tourists and lower class suburban sightseers along the Strip, couldn’t get enough of him. Gotteson had to learn quickly to harden his heart against that horde, or his singing-potency would have been decimated years ago. … He hated them. Hate hate hate hate hate hated them. No not all of them, but most of them—sweetheart-greenies wouldn’t blur the image sufficiently because the terrible truth was that, inside the hate, like a tiny perfumy current making its way slyly up through an enormous gaseous poison, was something like pity. He knew them from the inside. He was crucified on the cross of his pity for females…

Joyce Carol Oates has a knack for diving into the psyche of the disturbed. The most famous example of this is probably Zombie, her controversial serial killer novel based on Jeffrey Dahmer. That was the first thing I’d read by her, back when it was published, and it stunned me. I’d loved Red Dragon—which gets into the head of Francis Dolarhyde, a killer inspired by the BTK Killer (since captured) Dennis Rader—and I found it achingly sympathetic how he fights with the Dragon within!

Sadly, it’s a bunch of crap. Serial killers like what they do. The more charming types like Ted Bundy can make people who should know better think they are sad monsters, driven by forces beyond their control. But how many serial killers are found dead with a suicide note? Outside of fiction, that is.

No, the Maniac Bobbie Gotteson, the star of The Triumph of the Spider Monkey, probably gives these killers a more colorful internal life than they have, but it is more true to reality than the melodramatics of fairy-tale entertainments like Red Dragon, good as it is. Serial killers are boring and self-absorbed and often taken by rages, but everything ties back to themselves.

Bobbie Gotteson—found in a storage locker at the train station, thrown into the Newark foster and juvenile system where he is casually raped and passed around by his “mentor” and gangs of older boys—picks up a guitar and says he can “hum” songs out of the air, channeling the words. To himself, he is an innocent; “thoughts” make him do things. He doesn’t think them—thoughts think him.

If you’ve read Helter Skelter, the Mansonesque babble sounds not familiar but on the same frequency. While reading, I was amused to remember a high school friend becoming very angry that I had put the Beatles song “Helter Skelter” on a mixtape because, he said, “Manson said it made him kill.” This friend was a great Beatles fan and introduced me to “Penny Lane” and other songs of theirs, but this one was evil somehow—like the Beatles had somehow “hummed” the evil words out of the air. It’s a song about a large type of amusement park slide found in Britain, but in adolescence, every song is about you. And Manson—and Bobbie Gotteson—were both traumatized as youths and frozen in that adolescent mindset, or at least able to channel it and speak to young victims in Manson’s case.

As for Gotteson, he is lost in a world of delusions. We meet him after he’s imprisoned for slashing several women to death. But other than a scene of waking next to a woman and smelling blood, he only tells us of a time he chopped up a bunch of mannequins with his machete for a famous filmmaker.

Gotteson is beyond unreliable as a narrator; Oates uses footnotes in the novel to correct outright delusions. Gotteson thinks he’s on death row when he’s actually in an institution. His memories of the trial are comical, childlike persecution fantasies. We can’t tell what is real or what is a delusion, but the story compels by flashing from memory to memory of this guitar-slinging drifter who was invited to parties as a gag and thinks he was robbed of stardom. His identity is crumbling around him; the “spider monkey” is his animal side, the nasty nickname from his foster mother, the little monster who can launch itself at the face of anyone who attacks the more tender self within.

Oates is always compelling, and this story will appeal to fans of prison narratives where the killer is forced to confront his self.

The book also comes with a companion novella, Love, Careless Love, which follows one of the survivors of a Bobbie Gotteson slashing spree as she’s watched by a sentimental schlub hired by an investigator. This story is more Kafkaesque and paranoid in the Pynchon tradition:

Ganzfeld moved his head from side to side, eyes shut. I don’t her, Ganzfeld said contemptuously, I don’t know any of them. Missing persons, runaway persons, persons-about-to-he-slapped-with-injunctions, divorcées, thieving employees, victims, murderers, they come and they go, we get photographic evidence, evidence on tape, we guard them and escort them, we keep them under surveillance for months and then drop them when we’re ‘told to drop them. They come and they go, I don’t know this girl and you won’t either, don’t ask questions, don’t become involved, they come and they go. The wisdom of the profession is: Don’t exaggerate the humanity.

Ganzfeld hires “Jules” to watch Dewalene, who we learn survived a slasher attack where four other women died. She is a witness, and we don’t know if the D.A. or the defense have hired him. I put “Jules” in quotes because he is another man who seems to be losing his self; he thinks he killed a man in a drunken rage in a bathroom, and the guilt is crushing him. He loses himself in obsession, watching Dewalene long after his boss takes him off the case, helping her escape in her Jaguar into the California canyons. Or does he?

The 90-page novella is framed with “Jules” recovering from something. The last he remembers is turning down the secret road Dewalene points him to, and then she is gone and there’s a tarp in the weeds that looks like a body. He kicks it and only sees browned grass but is haunted by the spot, like he blanked out something terrible. It’s an interesting pairing with the longer story, two men with fragmented memories, perhaps to protect the fragile selves they have constructed or because they cannot face the real “Jules” or the “spider monkey” staring back in the mirror.

Another intriguing reprint from Hard Case Crime—two unflinching eviscerations of the wounded male ego by the masterful Joyce Carol Oates.