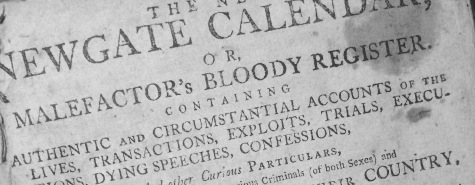

People have always loved reading about murder. Even back in the mid-18th century, the Newgate Calendar (also known as The Malefactors’ Bloody Register) titillated the public with gruesome accounts of true crimes. Ostensibly, this bulletin of executions at Newgate Prison published criminals’ confessions as a way to warn people about the mortal perils of their wanton ways, cautioning them against drinking, gambling, and prostitution.

Interestingly, in the early days of the Enlightenment, these criminals were seen as examples of the fate that might befall any of us who strayed from God’s path, and their executions were typically accompanied by a sermon that embraced the lost soul back into the fold. Only later in the Enlightenment did we learn to psychologically distance ourselves from these murderers, kidnappers, and thieves in order to see them as somehow monstrously “other.” Karen Halttunen explores this brilliantly in her admirably accessible study Murder Most Foul from Harvard University Press (2000).

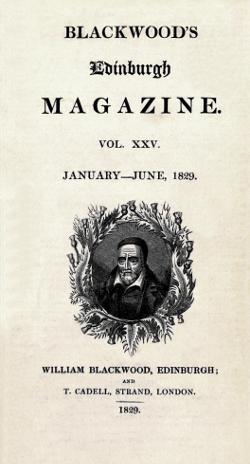

At the end of the 18th century and during the first half of the 19th, true crime accounts gave way to sensationalist fiction as the golden age of periodicals swept over England and then the United States. Blackwood’s Magazine, published in Edinburgh from 1817 to 1905, became to readers of its era as the television series Twilight Zone and Night Gallery did to viewers in the 20th century and fans of Black Mirror today. While many such publications were dismissed as “low literature” written quickly for money with the only goal of exciting the masses, the popular forms of such sensationalist horror combined with Romantic sensibilities to produce Gothic literature.

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, first published in 1818, represents one of the earliest works to show the true marriage of these forms. Not surprisingly, she wrote this stunning and groundbreaking novel while vacationing in Switzerland with her husband, the Romantic poet Percy Shelley, and his bosom friend Lord Byron, who was famously termed “mad, bad, and dangerous to know.”

This second generation of Romantic poets was sometimes known as Satan’s School—Percy Shelley was famously expelled from Oxford University for writing a pamphlet called “The Necessity of Atheism” (1811). However, in their poetic admiration for the awful sublime, these poets still shared a similar worldview with the admittedly more conservative first generation of Romantics, most notably the poets William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge.

Wordsworth and Coleridge would surely chaff at the comparison, but many of their poems in Lyrical Ballads can be read as prototypical Gothic works. Certainly, Coleridge’s “Rime of the Ancient Mariner” has many horrific elements. Even Wordsworth’s enigmatic short poem “The Thorn” can be read as a lyric narrative about grief and loss over a murder.

Another important aspect of their poetic project that connects Wordsworth and Coleridge to later crime fiction is the explicit desire in the preface to Lyrical Ballads to write “the real language of men in a state of vivid sensation.” They wanted to move away from the stilted, artificial language of “high poetry” to capture the grittier, more genuine language they heard by common people.

Over a hundred years later, the American detective writer Raymond Chandler echoes precisely these sentiments when writing about Dashiell Hammett’s hardboiled school of writing in his essay “The Simple Art of Murder” (1939): “Hammett gave murder back to the kind of people that commit it for reasons … and he made them talk and think in the language that they customarily used for these purposes.”

Chandler goes on to express his admiration for Hammett’s ability to achieve a sophisticated literary style that remains undetected by the general readership “because it was in a language not supposed to be capable of such refinements.” Like Gothic literature before it, crime writing conceals its literary embellishments and subtle social commentaries under the guise of a thrilling and dramatic plot with plenty of sex and violence.

Writing in the 1830s and '40s, Charles Dickens and Edgar Allan Poe represent two of the earliest writers to explicitly connect sensationalist, popular forms with more literary aims. Combining potboiler elements with a more socially conscious and realist sensibility, Dickens’s work often addresses criminality. While compared to that of Dickens, Poe’s writing is often more overtly grotesque and macabre in its exploration of criminality and perversity.

Additionally, it was Poe who, under the influence of Blackwood’s Magazine, perfected the first-person crime story, with its maniacally chatty narrator who might have been clever enough to get away with murder but who can’t shut up long enough to keep himself from confessing his crimes. The murderous tendency in these narrators seems to go hand in hand with a compulsion to confess, either to brag of their success or to assuage the unbearable throbbing of their guilty consciences.

We don’t always think of them in conjunction with Poe’s tales, but the noir masterpieces of the 20th century can trace their lineage directly back to antebellum America’s mad genius of the crime story. Poe’s approach undeniably inspires James M. Cain’s narrators Frank Chambers from The Postman Always Rings Twice and Walter Huff from Double Indemnity, as well as Jim Thompson’s narrators Lou Ford from The Killer Inside Me and Nick Corey of Pop. 1280. Further, 21st-century writers like Donna Tartt in The Little Friend and Gillian Flynn in Gone Girl have brilliantly updated this Gothic literary device of giving voice to a psychopathic narrator.

My own debut crime thriller, The Lawn Job, and the novels of these 21st-century bestselling authors owe much to the Gothic tradition. They definitely feel completely fresh and new to modern readers, but they also powerfully resonate with the true crime confessions published in the Newgate Calendar in the 18th century. As they say, blood will have blood.

To learn more or order a copy, visit:

opens in a new window![]() opens in a new window

opens in a new window![]()

Chuck Caruso, 19th-century Americanist and Poe scholar, teaches in the Department of English at Marylhurst University. As an author of dark genre fiction, Caruso's horror tales have been published in Cemetery Dance, Shroud, and Dark Discoveries, among other print magazines & anthologies. His western noir tales have been published by The Big Adios, Shotgun Honey, Flash Fiction Offensive, and Fires on the Plain. The Lawn Job is his first published novel. Caruso lives in Vancouver, Washington.