I’ve had a good amount of exposure to crime as a journalist, which influenced how I approached a task like editing The New York Times Book of Crime. But, of course, like all of us, my first responses to crime were crafted much earlier as a kid growing up in the Bronx.

I grew up in a section known as Riverdale, where the streets were leafy, and it was very safe—even in the ’60s and ’70s when New York City was more dangerous than it is today. So what I knew of crime as a kid didn’t come from walking any particularly mean streets. It came from reading the newspaper.

I remember seeing a headline in 1967 when Albert DeSalvo, the famed Boston Strangler, escaped from prison. It read something like:

“Strangler Headed for New York.”

I was eleven, and it was a time when parents left kids of that age alone in the house. I can remember looking up from my reading to think: Hmm. Massachusetts to New York. Not too big a haul for the Strangler. This would be a good time to make sure that the door is locked.

Ten years later, I felt much safer when David Berkowitz began his journey of terror through the lover’s lanes of New York City, killing people under the name of the Son of Sam. Yes, he was shooting people in my native Bronx. But I was working that summer as a camp counselor out on Long Island, in lovely East Hampton, and the Bronx and the danger unfolding there seemed very far away.

opens in a new window Until I picked up the paper one day to discover that Berkowitz had been caught—good—but with a machine gun—not so good—and that, when caught, he had been headed to the Hamptons—very, very not so good. I looked around my cabin in the woods. Hmmm, I thought. It is very unfortunate that no one ever thought to even put a lock on that door.

Until I picked up the paper one day to discover that Berkowitz had been caught—good—but with a machine gun—not so good—and that, when caught, he had been headed to the Hamptons—very, very not so good. I looked around my cabin in the woods. Hmmm, I thought. It is very unfortunate that no one ever thought to even put a lock on that door.

That’s how crime grabs us, isn’t it? Viscerally. Personally. “My god, I can’t believe that happened to that person. Could that happen to me?”

Stories about crime appeal to the voyeur in us. Readers are stirred by the possibility that—but for fate—they too might have suffered. So, for all our genuine repulsion at violence, crime makes rubberneckers of us all. Which explains, of course, how I came to include articles about DeSalvo and Berkowitz in The New York Times Book of Crime.

But what else belonged, and what would fit? Should this be a catalogue of the best-written crime stories or the most important?

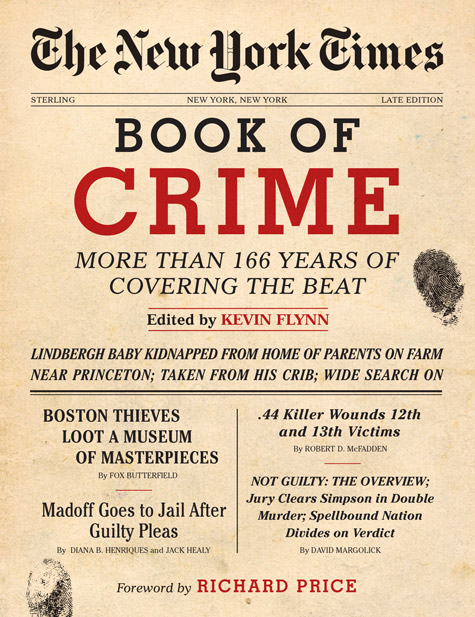

It seemed clear from the outset that readers would want to see the most vital of the crime news that The Times had reported on. That required reading through and whittling down the great sweep of articles published during the newspaper’s 166 years of history. Everything from Jesse James to Jeffrey Dahmer, from Jack the Ripper to Bernie Madoff. Once I realized how incredibly difficult it was going to be to find space for just the highlights of the highlights, it became clear that it made no sense to discard the essential to make room for the interesting but offbeat.

So we chose instead to focus on finding the best, most compellingly written of the stories that captured the crucial crimes that have occurred since 1851, when The Times began publication. Luckily, I think, readers will still find surprises. For many people, including myself as I began this journey, the so-called “crimes of the century” of yesteryear have long faded from memory.

For example, I can remember the fear that took hold in me in 1966 when Richard Speck murdered eight nurses, one by one, in their Chicago dormitory—the lone survivor being a nurse who escaped his notice by hiding under a bed. But I imagine that horror is largely unknown to many born after me.

And how many people know much about the extraordinary 1906 murder of Stanford White, a legendary architect killed in jealous rage by the husband of Evelyn Nesbit, the country’s first supermodel. The Times’s report, included in the book, is ripe with detail.

Similarly obscure was the strange case of America’s first acknowledged serial killer, H. H. Holmes, until Erik Larson opened our eyes in his brilliant 2003 bestseller The Devil in the White City. Holmes had earned a medical degree from the University of Michigan, but nonetheless demonstrated little interest in the healing arts. He chose instead to open the World’s Fair Hotel in Chicago, just a few miles from the fairgrounds for the 1893 World Columbian Exposition. Then, he advertised for guests and murdered some of them in rooms he had specially constructed to conceal their screams.

We decided to include Holmes’s obit in The New York Times Book of Crime. It does a good job of summing up the span of his life. We could not fit a second article about him, published on July 25, 1895, but I continue to be struck by the almost jocular tone with which it began:

“It is regarded as a rather uneventful day in police circles when the name of H. H. Holmes is not connected with the mysterious disappearance of one or more persons who were last seen in his company.”

A second question my researcher, Susan Beachy, and I faced was whether the articles we included should cover crimes that were international in scope. We decided that, yes, it was very important to include crimes that had either drawn worldwide focus or had broad international consequences. So, readers will find a report from the city in Italy where a young student, Amanda Knox, was charged with a murder in a case that would challenge the Italian justice system, and another from a parade ground in Egypt where Anwar Sadat, an architect of a heralded Middle East peace plan, was assassinated.

Some of the crime recounted in the book occurred in New York, which has long been a focus of my newspaper. I’ve personally covered my share of murders and the like over the years, especially during the period of 1998–2002 when I served as The Times’s police bureau chief, stationed at headquarters in lower Manhattan.

When I arrived at headquarters, New York no longer held any claim to a title like crime capital of the United States—a designation that it, of course, never embraced, even during the years when the annual number of murders crested 2,000. But it still had a long association with violence, organized crime, and political scandals that often drifted into the seedy—like the prostitution scandal that entangled former New York governor Eliot Spitzer.

The Spitzer saga is recounted in the crime book, and we decided to do an entire chapter on the mob. Here, again, the massive amounts of gangster coverage made the choices difficult. We tried to collect a group that would give some sense of the evolution of organized crime plus insight into its impact and lore. But there was no room for the many mob hits that, post Hollywood, have come to seem more like fictional events than the unfortunate fate of real, if flawed, people.

So, readers will encounter the rubout of Carmine Galante, an organized crime chieftain, during lunch on the patio of an Italian restaurant in Brooklyn. They will not read about the assassination of Paul Castellano, the Gambino crime boss shot down as he stepped from his car into a midtown Manhattan steakhouse. There was just no room. (They will read a lot, though, about John Gotti, the mob boss who orchestrated the Castellano hit.)

I’ve been indebted throughout this process to the fact that I once spent so much time in one of the great crime writing centers of the United States. It’s called the Shack, and it’s the press room in New York Police headquarters, home to all the reporters who cover the NYPD on a full-time basis.

When I was there, the Shack was a warren of cramped offices on the second floor of headquarters. Space in The Times’s office was particularly tight. Wires from old TV hookups hung out of the walls. Multiple phone lines crossed the floors. It was like working in a dirty, very early model space capsule.

The Shack name, though, actually dates from an earlier era. In 1875, the reporters were tossed out of headquarters for some transgression, and they ended up renting space in a tenement across the street—thus the name for the press room. Years later, when the reporters were let back into headquarters, the name returned with them and stuck.

I’m told that, since I left, the offices have moved across the second floor without gaining any appreciable space or losing any of its grimy charm. But the importance of the Shack was never about the accommodations. It was about the people who inhabited it—some of them for decades, outlasting multiple police commissioners and most of the police officers they covered.

At times, the cop reporters functioned like New York’s institutional memory of crime, capable of remembering discarded police policies, ancient nicknames, and old crimes—like the 1980 murder of a violinist at the Metropolitan Opera House. She disappeared during a break in a performance by the Berlin Ballet. Her body was not discovered until the next morning when it was found in a ventilator shaft.

We selected The Times’s report of the 1981 jury verdict in that case for the book. Craig Crimmins, a stagehand working that night, was convicted in her death. He was 21 and, by his own account, drunk at the time of the murder. He snapped, he said, when the violinist, Helen Hagnes Mintiks, refused his sexual advances. Helen was 31 and a promising talent. She had been bound and gagged and stripped naked before being kicked into the ventilator shaft. She died in the fall.

Newspapers at the time called it “The Murder at the Met.” The perpetrator was dubbed “The Phantom of the Opera.” It was interesting on an almost cinematic scale. It was the kind of crime that makes for fascinating reading. But—I have worked to remind myself—it was not a work of fiction, not something that could be erased like an old DVD.

Crimes like this, I hope readers and writers like myself can remember, were real events that affected real people. And even if they took place 100 years ago, it seems clear that, for some people, they still carry a real measure of both sadness and pain.

To learn more or order a copy, visit:

opens in a new window![]() opens in a new window

opens in a new window![]()

Kevin Flynn is an investigative editor whose work has helped earn The New York Times numerous awards, including a 2009 Pulitzer Prize. He served as the newspaper’s police bureau chief from 1998 to 2003 and, in 2005, he cowrote with Jim Dwyer 102 Minutes: The Unforgettable Story of the Fight to Survive Inside the Twin Towers (Henry Holt), a bestseller that was a National Book Award nonfiction finalist.