When searching for inspiration for Beloved Poison, the dark and extraordinary history of 19th-century medicine offered an evocative, alarming, and exciting world. The setting for my novel was an infirmary. Ramshackle and decaying, I used Old St. Thomas’s Hospital in London as my template.

Instead of being places of hope and cure, in the mid-19th century, infirmaries were dark and foreboding institutions that were filthy, crowded, and unventilated. Before the link between dirt and disease was fully understood, doctors might pass from the mortuary to the hospital wards without washing their hands—transferring death to everything they touched.

Lack of understanding about the ways in which disease was spread was also evident in the wider city environment. The stink from decaying matter and the great quantities of human and animal waste that gathered in pits and pools, in mounds and middens, would have made the air intolerable to breathe and would have infected homes and gardens to an inescapable degree.

Watercourses would have been choked with refuse—offal, domestic waste, sewage and industrial effluent. Falling into any body of water in any Victorian city would almost certainly result in death, and drinking water drawn from a street pump could signal a painful and undignified end for hundreds if the cholera was in town.

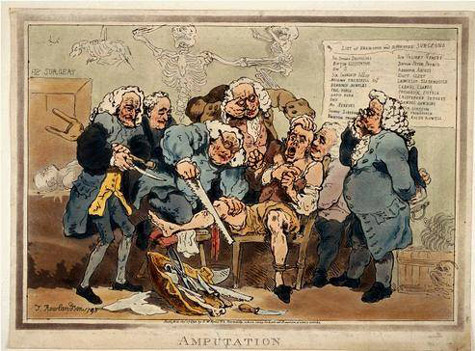

The practice of medicine was also deadly and agonising. Before ether or chloroform became widely used in the early 1850s, operations would take place without anaesthetic—the patient numbed only with alcohol or opium. For this reason, surgeons prided themselves on the speed with which they could perform complex operations.

Individual doctors struggled to make a name for themselves and tried out whatever methods might help to further their careers. My favorite character is John Hunter, the 18th-century anatomist whose methods and practices inspired medical men for generations.

Hunter’s desire to know more about the human body knew no bounds. He insisted that all the senses were used when performing a post mortem—including taste! Surrounded by admiring students, Hunter would remove organs from the anatomised body, slice them up for the microscope, pickle them in formaldehyde, or inject their arteries and veins with coloured resin. The results were both beautiful and disturbing.

Once all the soft parts had been dealt with, the remains were boiled up in a great copper cauldron and the bare bones wired together into a skeleton. Hunter’s experiments on those who were still alive were even more unsettling, particularly his practice of transplanting teeth. He recommended that the teeth of children be used, and there were stories of poor children as young as twelve rendered toothless, their new, second teeth transplanted for money into the mouths of wealthy clients.

Many medical men experimented on themselves, too, noting the results of poisons they ingested and gulping down salted water to make themselves sick, hopefully before a lethal dose was ingested. Toxicologist Robert Christison is one such famous example. Perhaps worse still, in an act that seems quite extraordinary to us today (and probably also astounded his peers and dismayed his long-suffering fiancé), John Hunter tested the idea that gonorrhoea and syphilis had the same origins by smearing infected pus onto his own penis.

There is evidence of women cross-dressing in order to enter the medical profession—something I drew upon in my novel. Dr. James Barry studied medicine at Edinburgh University from 1809 to 1812. A commissioned officer in the British army, Barry worked all around the world. Upon his death, it was discovered that Barry was a woman who had hidden her identity all her life in order to practice medicine. Barry even met Florence Nightingale—and kept her waiting in the hot sun for over an hour.

But what about the patients? Cholera, typhus, and consumption are just three examples of diseases for which there was no cure, whilst the pox (syphilis) and the clap (gonorrhroea) offer a writer limitless potential for madness, horror, and death.

Treatments were sometimes poisonous, often useless, and always vile. Mercury was used to treat syphilis, resulting in tooth loss, hair loss, and the production of copious quantities of black saliva—not to mention the possibility of death. Opium—often in liquid form (laudanum)—was prescribed for everything from insomnia to toothache. Addiction and overdose were common. Leeches were employed by all doctors, and in the large infirmaries, thousands of them were used every year. Venesection (bloodletting) was standard practice too, so much so that one student described the hospital floors as “running with blood…it was difficult to cross the hall without fear of slipping.”

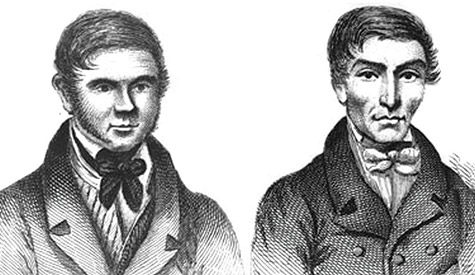

Of course, no survey of the gruesome history of mid-19th-century British medicine would be complete without mentioning the resurrectionists who dug up the recently deceased to provide subjects for the anatomists and their students. Grave robbing would have been a familiar undertaking in the UK for most medical students prior to the Anatomy Act of 1832. Those too squeamish to undertake the activity themselves, however, might pay others to do the job for them.

Burke and Hare are the most infamous examples. Grave robbers for Dr. Robert Knox at Edinburgh University, William Burke and William Hare turned to foul means when the supply of newly buried corpses dried up—in 1828, they murdered between 16 and 30 men and women and delivered their bodies up to the university medical school. When the pair were caught, Hare turned Kings Evidence and escaped the gallows. Burke was hanged and his body anatomised by the surgeons he had once supplied. His skeleton still stands in the anatomy museum at Edinburgh University. Dr. Knox never recovered from the scandal.

From leeches to venesection, cross-dressers to self-poisoners, the history of medicine is a rich and gory source for any writer of historical crime fiction to draw upon—with the additional benefit of reminding us how lucky we are to live in the 21st century.

To learn more or order a copy, visit:

opens in a new window![]() opens in a new window

opens in a new window![]()

E. S. Thomson has a Ph.D. in the history of medicine and works as a university lecturer in Edinburgh. She was shortlisted for the Saltire First Book Award and the Scottish Arts Council First Book Award for Beloved Poison. Elaine lives in Edinburgh with her two sons.