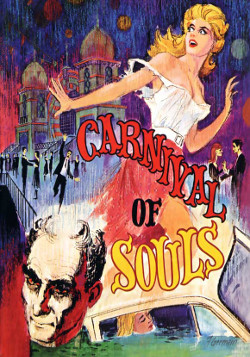

It’s hard to know where to begin in writing about Carnival of Souls, the eerie cult classic horror film from 1962, which has just been given the Criterion Collection treatment in a new Blu-Ray edition. There is so much intriguing back story to the movie.

One aspect of the odd but memorable film that stands out to me is its un-likeliness. There’s every reason why the movie shouldn’t have been any good. Herk Harvey, its producer and director (who also played a significant acting role), never made another feature film besides Carnival. Its leading role was portrayed by actress Candace Hilligoss, who only has one other full-length motion picture role to her credit. Its inspiration and physical focal point—a rundown, disused resort complex in Salt Lake City—is a place that would have seemed, to most people at the time of the film’s making, more suitable for the scrap heap than as a location for key scenes in a motion picture. The movie was filmed in about three weeks and on a budget that would have been considered laughably small by any Hollywood production outfit.

But then, as a film critic states in one of the mini documentaries that’s part of the extras in the Criterion version of Carnival, Harvey took all of those apparent drawbacks and turned them around so that they were pluses for his movie.

The director’s work in films prior to Carnival had been as the maker of a slew of educational and industrial shorts for a Kansas-based firm called Centron. So, he knew how to work a movie camera and how to use it to create a story and atmosphere. But, with Harvey not being a polished motion picture maker, his work on Carnival has an innocence to it that is so much of what makes it work.

Hilligoss was a Lee Strassberg-trained thespian and an attractive enough leading lady, yet there’s an awkwardness to both her physical appearance and her acting that wouldn’t have worked for a major studio film production, but that made her perfect for the low-budget Carnival. The other actors—not counting Sidney Berger, who was a theater student at the time and who is excellent in a B-movie way as Hilligoss’s character’s sleazy, lecherous neighbor—are so wooden in their playing that they look more like people who would have been given parts in small-town local TV commercials than in a feature film; but the bit part players’ stony acting works in Carnival, adding to its offbeat and unreal tone.

And then, that aforementioned locale: the rundown Salt Lake resort structure that caught Harvey’s eye while he was traveling home to Kansas from a vacation in California. The place—which had once been a thriving gathering spot where people danced to music by the likes of Glenn Miller and Harry James, but was now just an unused structure ready for the wrecking ball—had a ghostly quality to it that made it ideal for the hallucinatory tale Harvey wanted to tell in his film.

The story of Carnival, which was written by Harvey’s Centron collaborator, writer John Clifford (who has co-written songs with David Lynch’s musical associate Angelo Badalementi), starts out like that of a typical teenage scare educational film of the kind that Harvey usually made. Two groups of youngish people riding in cars near a bridge decide to goof around in a playfully competitive way in their respective vehicles, and one of the groups drives their car off the bridge and into the river below. Rescue attempts to pull their vehicle out of the water are going nowhere, when one of the occupants of the sinking car suddenly emerges, having somehow escaped the drowning fate that seemed assured for her and the other people in the vehicle that went under.

The young woman—Hilligoss’s character, Mary Henry—appears to be in a trance. Nobody can understand how she got out of the sinking car, and she appears too spaced out to explain her Houdini-like feat. And, before we can go much further into that mystery, suddenly Henry is seen playing some notes on a pipe organ in an organ factory. It seems she is now ready to leave this town and move out to Utah, where she will work as the resident organist in a church.

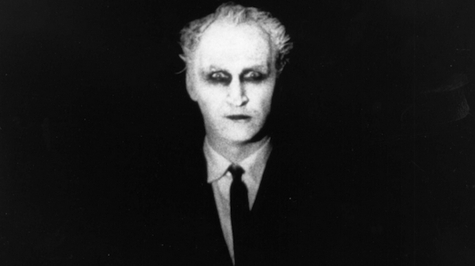

Henry, a quirky young woman who is a resolute loner and who makes statements like “I don’t belong in the world” and “Something separates me from other people,” is terrorized by a ghostly figure (Harvey’s ghoulish, white-faced character “The Man”) who stalks her on the drive to Utah.

Then, once settled in her new hometown, she is mistreated by nearly everyone she encounters, whether it’s her greasy, pawing neighbor played by Berger, or random others who either scold her about her unsocial ways or treat her likes she’s invisible. And, meanwhile, Henry keeps seeing “The Man” and other deathly people who appear to be beckoning her to join their living dead world, and she feels morbidly drawn to an otherworldly-looking pavilion in the town (part of the aforementioned dilapidated resort), which people tell her is off limits.

Clifford’s story was well written, but it’s the atmosphere that really makes this film work. Harvey, who has been quoted as saying he wanted Carnival to have the look of an Ingmar Bergman film and the feel of one made by Jean Cocteau, created a vividly haunting feature that feels like a series of visions one would encounter in a dream state. As one of the commentators from the documentary mentioned above says, what makes the hazy aura of the movie so genuine is that, like in our dreams, many of the people and situations that come about are mostly normal, yet something about all of it goes a little screwy.

Like when Henry is shopping for a dress to wear at her new job and the department store sales lady, who had been helping her in the usual way up to a point, suddenly doesn’t seem to see or hear the stricken woman anymore. All of Henry’s encounters with others (besides those with the zombies) have that quality of being believable to a point, but then taken to an uncanny extreme, just like the visions we all see in our minds’ eyes when we’re dreaming. Henry’s disturbing interactions with others, juxtaposed with her continued vague harassment by “The Man” and the other zombied-out people who keep turning up, forms a perfect nightmare for the socially isolated woman. And, all along, there’s that ghost town pavilion that people say she shouldn’t go to, but to which she feels inevitably drawn. The film is an unlikely masterpiece of surrealistic horror.

When we rent or buy a Criterion edition of a movie, of course we do so largely for the glorious extras that come with the disc. The bonus features that accompany this release are, like the movie itself, a little off, but just right for the purpose.

My favorite part of the extras is a 27-minute series of outtake footage snippets, accompanied by some of the spooky pipe organ music played by Gene Moore, which is such a key aspect of the film. There’s also a selection deleted scenes; the documentary I have discussed earlier, in which a handful of film buffs offer their thoughts on Carnival; and another documentary made by a Kansas filmmaker in 1989, around the time Carnival was enjoying a resurgence and re-examination. Additionally, there’s audio commentary by Harvey and Clifford from ‘89, excerpts of the educational/industrial films produced by their employer Centron, a booklet that comes with a Carnival poster on one side and an essay by film writer Keir-La Janisse on the other, etc.

My favorite part of the extras is a 27-minute series of outtake footage snippets, accompanied by some of the spooky pipe organ music played by Gene Moore, which is such a key aspect of the film. There’s also a selection deleted scenes; the documentary I have discussed earlier, in which a handful of film buffs offer their thoughts on Carnival; and another documentary made by a Kansas filmmaker in 1989, around the time Carnival was enjoying a resurgence and re-examination. Additionally, there’s audio commentary by Harvey and Clifford from ‘89, excerpts of the educational/industrial films produced by their employer Centron, a booklet that comes with a Carnival poster on one side and an essay by film writer Keir-La Janisse on the other, etc.

What struck me the most in watching all of the bonus material was that same thing that occurs to me about the movie: the un-likeliness of it all. When they appear in the documentaries made about Carnival, Harvey, Clifford, Hilligoss, and Berger all come across as people who, if you didn’t know about the movie and their associations with it, you wouldn’t expect to have ever taken part in a critically acclaimed film. Harvey and Berger are somewhat comfortable as public speakers when discussing the movie in front of audiences and interviewers, but both are far from smooth in this way.

Clifford, meanwhile, appears fully camera shy and like a man with a lot of great ideas but no knack for explaining them orally. Hilligoss comes off like she does in the movie—almost glamorous, but too awkward to be a starlet. All of them feel more like insurance company employees making stiff speeches at a company banquet than a group of movie people discussing their roles in making one of the most durable cult films ever cut.

But, again, that’s such a big part of the beauty of Carnival of Souls—that it shouldn’t have worked but did.

Brian Greene writes short stories, personal essays, and reviews and articles of/on books, music, and film. His work has appeared in 25+ publications since 2008. His pieces on crime fiction have also been published by Noir Originals, Crime Time, Paperback Parade, The Life Sentence, Stark House Press, and Mulholland Books. Brian lives in Durham, North Carolina.

His writing blog can be found at: http://briangreenewriter.blogspot.com. Follow Brian on Twitter @greenes_circles