I’m not 100% sure why I set my latest novel in the 1970s.

You’ll find me much more one for a 1940s cinematic take on film noir, with an eye on the ’50s.

I cannot count how many times I’ve seen Howard Hawks’s The Big Sleep, John Huston’s The Maltese Falcon, Billy Wilder’s Double Indemnity, Joseph H. Lewis’s Gun Crazy, Carol Reed’s The Third Man, Jacques Tourneur’s Out of the Past, Tay Garnett’s The Postman Always Rings Twice, Akira Kurosawa’s Drunken Angel, or Robert Siodmak’s The Killers.

But as a child?

Well, I did grow up in the ’70s.

My parents were right into that decade’s detective mysteries and cop escapades on the box, which I watched also: programs like Starsky & Hutch, The Rockford Files, McMillan & Wife, Baretta, and The Mod Squad.

Some brilliant related movies arose then to, such as Roman Polanski’s Chinatown, Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver, James William Guercio’s Electa Glide in Blue, and Robert Altman’s The Long Goodbye—not to mention a batch of superb Japanese yakuza films starring Bunta Sugawara.

And, I still remember one evening when my mum came home after a night out at the pictures and she recounted her horror at a dismembered horse’s head in bed that the audience glimpsed in a screening of The Godfather.

When I started to conjure up a hardboiled comic book named Trista & Holt on New Year’s Eve 2014—a revisionist take on the medieval romance of Tristan and Iseult—I began by setting it in the 1940s.

Yet, a couple of days later it had swapped eras for the ’70s.

Trista & Holt then morphed into the novel I just finished, which I renamed Black Sails, Disco Inferno.

The horrors of the endemic fashion helped (my key protagonists being more swayed by earlier, cooler wardrobe choices of Brigitte Bardot—Trista—and Patrick McGoohan in The Prisoner—that’s Governal).

Plus, I could have fun with the cars and the songs—especially disco.

In my stories, music is a key component, often used to soundtrack particular moments or moods. The flippancy of disco and ’70s pop fluff can counter intuit the gravity of particular situations, or embrace them.

After all, this was a revisionist take on a medieval yarn that, at its root, is a tragic love story, and which later influenced Romeo and Juliet and King Arthur and Guinevere. Setting it in a crime-ridden 1970s not only grounded the drama, but also added some essential levity.

Thus, I could make tips of the hat not only to the original tale, but to Michael Corleone and David Starksy, real-life TV soap advertising from forty years ago, fashion designers like Kenzo Takada or Giorgio di Sant’ Angelo, Studio 54, the origins of punk, flares, body shirts, even Saturday Night Fever and Grease.

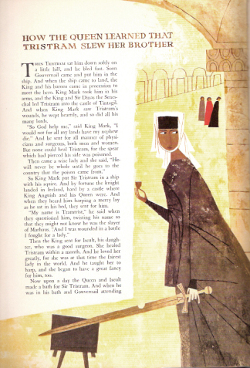

Yet, at its heart, Black Sails, Disco Inferno is a love-letter to the hardboiled nature of my favorite writers—Raymond Chandler, Dashiell Hammett, James M. Cain, Ed Brubaker, and Ross Macdonald—and a reimagining of an old-school tragedy I loved as a kid, thanks to this pictorial version of Tristan and Iseult by artists Alice and Martin Provensen that sat in a 1959 tome called The Golden Treasury of Myths and Legends.

Yet, at its heart, Black Sails, Disco Inferno is a love-letter to the hardboiled nature of my favorite writers—Raymond Chandler, Dashiell Hammett, James M. Cain, Ed Brubaker, and Ross Macdonald—and a reimagining of an old-school tragedy I loved as a kid, thanks to this pictorial version of Tristan and Iseult by artists Alice and Martin Provensen that sat in a 1959 tome called The Golden Treasury of Myths and Legends.

The tricky part was combining these two passions.

Given the nature of society a millennium after Tristan and Iseult first arose, why not reverse the sexes of our protagonists? Tristan, as Trista, becomes a young woman who’s world-wise and equipped to handle the horrors of a violent, almost-contemporary world, while Iseult morphs into Issy Holt, son and heir of a crime family who comes across (initially) as little more than a constantly-inebriated social wallflower.

On the side, I also tinkered with a subtext of the original story (the kingdoms of Ireland and Cornwall competing for dominance), taking essential characters, cultural nuggets, and situations to reboot them in the fabric of this revised story.

Not all of it translated well, so don’t expect a purist approach.

But, if you’ve read the legend, you might know vaguely what to expect: the riffs on subterfuge, revenge, a love-potion, passion, remorse, betrayal, and a set of black sails.

Otherwise, I’d suggest holding onto your hats—and if you’re lacking one, more the shame.

To learn more or order a copy, visit:

opens in a new window![]() opens in a new window

opens in a new window![]() opens in a new window

opens in a new window![]() opens in a new window

opens in a new window![]()

Andrez Bergen is an expat Australian writer, journalist, DJ, artist and ad hoc saké connoisseur who's been entrenched in Tokyo, Japan for the past 15 years. He makes music as Little Nobody and Funk Gadget, and ran groundbreaking Melbourne record label IF? for over a decade from 1995. Bergen has also written articles for papers and magazines such as Mixmag, The Age, Anime Insider, Australian Style, Impact, Remix, Beat, Yomiuri Shinbun, and Geek Magazine. He published noir/sci-fi novel Tobacco-Stained Mountain Goat in 2011, the surreal fantasy One Hundred Years of Vicissitude through Perfect Edge Books in 2012, comicbook/noir/pulp tome Who is Killing the Great Capes of Heropa? (2013), a collection of short stories and archival articles called The Condimental Op (2013), a surreal coming-of-age tale with crime/noir undertones titled Depth Charging Ice Planet Goth (2014), and the horror/noir comedy Small Change (2015).