Horror audiences take so much for granted. So many of the monsters, tropes, and scenarios of the genre have been hammered into us over the years that we've become quite jaded.

“Oh,” we say halfway through the trailer or synopsis blurb, “another serial killer story—yawn.”

We fail to appreciate that clichés had to start somewhere. As difficult as it may be to believe, the pop culture landscape hasn't always been awash with obsessive stalkers, murderous Peeping Toms, and slashers with severe mommy issues and low impulse control.

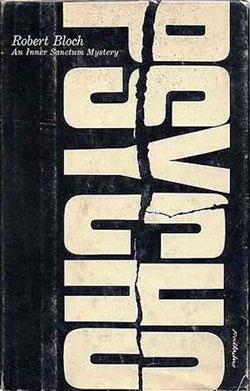

Every monster starts somewhere—and it's only fitting that the archetypal slasher appeared in a story titled Psycho.

William Bloch's best known novel didn't just break the mold, it created it. Were their crazed madmen before Norman Bates? Of course; and plenty stalked the silver screens or tread the yellow pages of cheap, thrilling novels.

William Bloch's best known novel didn't just break the mold, it created it. Were their crazed madmen before Norman Bates? Of course; and plenty stalked the silver screens or tread the yellow pages of cheap, thrilling novels.

But prior to Psycho's release—the book hit stands in 1959, with Alfred Hitchcock's masterpiece quickly following a scant year later in 1960—there had never been a fictional murderer quite like sweet, unassuming Mr. Bates.

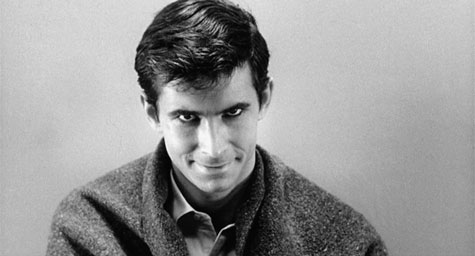

Before Norman's entrance into the public eye, the malevolent murderers of cinema and pulp fiction were easy to pick out of a crowd. Their bloodshot eyes rolled in deep-set sockets; they slavered like rabid beasts; they were malformed, animalistic, or visibly wrong.

No one could mistake them for anything but what they were: dangerous and inhuman.

But for all that we fear the obviously monstrous, what is truly terrifying is the idea that we could be hoodwinked. Sure, the howling beast in the woods is scary. But, what about the smiling face you invite into your home? The friendly neighbor you nod at over the white picket fence? The “good boy” you would never, ever, not in a million years suspect of being capable of bloody, horrific violence?

Evil is never scarier than when it hides behind the normal, mundane, and oft-ignored visage of the everyday. As is commonly the refrain in zombie fiction: the most frightening creature, and truest threat, is man himself.

And Bloch proved that in chilling detail with his ultimate creation, Norman Bates: the sweet, soft-spoken, smiling proprietor of a small roadside motel. Norman is educated and polite. Norman dresses simply and keeps to himself. Norman is devoted to his mother. Norman is everything a young man ought to be—until you realize he's not.

Audiences already knew to fear the “Other,” but Psycho taught them to fear one another. Anyone could be a madman in disguise. Your neighbor, the mailman, your teacher—hell, even your brother could be hiding dirty, violent secrets in his cellar.

For one of the first times in horror, mental illness became a driving motivation behind murderous impulses. Norman isn't entirely in control of his actions because he's sick. He's suffering a psychosis—a split personality—and truly it's Mother doing all of these barbarous things.

(This isn't to say that Bloch, and the other writers to follow, was excusing Norman's behavior: they were simply explaining it, revealing that a lifetime of abuse and mental instability could turn even the sweetest of people into an unpredictable killer.

And, of course, this isn't to say that mental illness is always to blame when people murder—an overwhelming percentage of those suffering mental illness are peaceful, non-violent folks, and suffer from enough societal stigma as it is. But, well, the title of the book/movie is Psycho, after all. But I digress.)

Psycho brought the destructive nature of obsession to the fore. In many ways, Norman was the herald of every nice-guy-turned-killer story to follow—the precursor to the stalkers, sickos, and Peeping Toms that have since become a fact of life and staples of the horror genre.

Without Psycho, there'd be no Scream. Without Norman, there's a good chance we wouldn't have Jason, or Freddy, or even Michael Myers. When he donned Mother Bates's dress and stabbed the source of his “impure” thoughts, he paved the way for every masked killer seeking their own twisted revenge, punishing the “immoral” for everything from pre-marital sex to simple youthful rebellion.

Horror truly owes Mr. Bates a debt of gratitude. Without him, the landscape would be a helluva lot tamer and far less paranoid.

And though Norman first exploded onto the scene—thanks in no large part to that unforgettable shower sequence—over fifty years ago, time has hardly dulled his relevancy. Or his popularity.

The success of the Bates Motel television series—starring Vera Farmiga as Norma “Mother” Bates and the once cherubic, now gangly Freddie Highmore as dear ol' Norman—comes as no surprise. We've known what happened to 30-something Norman, and then 50-something Norman, for decades thanks to Bloch's original novels and the trilogy of movies.

(Most forget that Psycho II and Psycho III exist, and perhaps rightfully so: they don't come even close to approaching the greatness of Hitchcock's or Bloch's original. But still, they are there for perusal.)

But what about Norman's childhood and formative teenage years? What about Mother herself? Those were still blanks waiting to be filled, and Bates Motel is doing a fine job of coloring in the question marks. Naturally, there's plenty of scandal, intrigue, murder, and incestual mother-son bonding in every episode. Norma herself has proved to be as unhinged—if not more—than her darling son, and fans have been eating it all up with a long spoon.

No wonder Norman turned out to be so repressed and psychotic. An early life like that would drive plenty to taxidermy and shower stabbing.

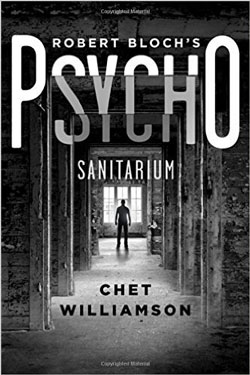

And now Chet Williamson has given us a brand new chapter of the Norman Bates saga. Psycho: Sanitarium fills out one of the remaining gaps—the years that everyone's favorite Mama's boy spent in a mental institution in the wake of killing Miss Crane and the snooping Detective Arbogast.

And now Chet Williamson has given us a brand new chapter of the Norman Bates saga. Psycho: Sanitarium fills out one of the remaining gaps—the years that everyone's favorite Mama's boy spent in a mental institution in the wake of killing Miss Crane and the snooping Detective Arbogast.

Whether you're a long-time fan of the Psycho story or not, Williamson's addition is, frankly put, a stupendous one, and very true to the first story's spirit. Not only do we gain insight into Norman's fractured psyche and personal demons, but we also have a slew of new characters that mirror and reflect his psychosis and darker desires.

Sanitarium does a brilliant job of elaborating on Bloch's original premise: that anyone, even the most outwardly respectable or seemingly normal people, can be harboring violence and cruelty in their hearts. True evil comes more often from within than without, and in the claustrophobic confines of the State Hospital for the Criminally Insane, there are both angels and demons walking the halls—and not all of them sleep in locked cells at night.

While Norman struggles to emerge from a catatonic state induced by his “Mother” personality, he dreams of both crimes already committed…

His left hand rose in front of his eyes and grasped the edge of the curtain, and as it did he noticed that his arm was clad, not in a shirt, but in a cloth printed with a pattern of flowers, with white lace trim at the cuff. The surprising sight made him want to stop and examine more closely what he was wearing, but he couldn't. He could only push back the curtain.

But in the split second before he did, the girl's scream began, piercing through the roar. And then the curtain no longer separated them, and he clearly saw the wet, naked girl revealed, standing in the watery stream, her face twisted toward him, her startled eyes wide in shock, her screaming mouth open wider than her eyes.

Her nudity, her vulnerability, her fear, all inflamed him, and it was when he reached out his right hand to touch her bare flesh that he finally saw it was not empty.

He saw what he was holding…

…and of crimes unfolding around him in the hospital. Crimes he can't possibly be connected to—can he? No, not with his door always firmly locked and the kind Dr. Reed and Nurse Marie checking in on him every day.

He can't be responsible for the mysterious disappearances, because he's getting better, isn't he? He's fighting Mother's diabolical influence, he's learning how to speak for himself again, and he has a new confidante in long-lost brother Robert, who understands him so well.

Besides, everyone knows the hospital is haunted. And who can say what angry ghosts are capable of?

Williamson layers in plenty of intrigue and surprising twists, shaking things up for those who consider themselves adept at predicting the next horror beat. He's also a maestro at building and maintaining tension, and knows just how to work his “haunted asylum” atmosphere for all it's worth.

The twisting, writhing snake of a story unfolds like the best late-night horror film, evocative of all of those yellowed paperbacks read with quickening breath and racing pulse. Before long, you suspect everyone of anything, and find yourself sympathizing with poor, confused Norman.

Maybe a murder here and there can be a reasonable thing after all? When it's for the greater good—when the victims are truly bad people—when no one really cares…

It's a tough sell, making a psychotic murderer into a hero, but Williamson just about manages it.

Because, after all:

I’ve watched a season of Bates Motel during a Netflix binge, and I’m a bit ashamed to say I’ve never sought out the source material. I haven’t seen Hitchcock’s movie or read the book. One of these days I need to see the original film — I’ve seen plenty of references to the shower scene but haven’t seen the thing itself.