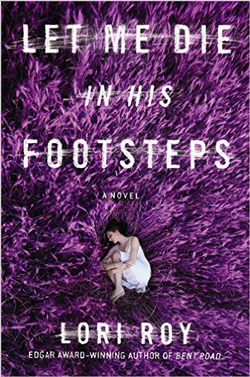

Let Me Die in His Footsteps by Lori Roy explores the secrets of two families touched by an evil that has passed between generations. Nominated for the Edgar Award for “Best Novel.”

Let Me Die in His Footsteps by Lori Roy explores the secrets of two families touched by an evil that has passed between generations. Nominated for the Edgar Award for “Best Novel.”

Dead milk snakes, nailed up to ward off evil, amid fields of lavender and tobacco set the unsettling tone for Edgar Award winner Lori Roy’s haunting third novel, itself a 2016 Edgar nominee for “Best Novel.” In alternating time periods—1936 and 1952—and voices, Roy recounts the twisted lives of two generations of families in rural Kentucky, focusing primarily on the women who have what the country folk refer to as the “know-how,” or a sixth sense that danger, or, once in a great while, delight, is on the horizon.

The sections set in 1936 are narrated by the teenage Sarah Crowley, the elder of two sisters, and the one without the know-how. It’s her younger sister, Juna, whose black eyes—not muddy brown, or dark hazel, but true black—send spasms of fear through her own father, who possesses the gift.

But it’s also Juna whose mother, after Juna’s birth, received not the widespread cooing and adulation from the neighboring women traditionally reserved for those with new cuddly infants, but rather a blunt caution. “I’ve no intent to be unkind,” said the woman who would one day become Sarah’s mother-in-law, “but be wary of this child. Take extra care.”

There’s nothing complimentary about this backhanded warning. Juna’s status as the “cursed”—or curse-causing, take your pick—Crowley was cemented when her and Sarah’s mother died, 10 days after giving birth to her third and final child, the girls’ younger brother, Dale. Things do not improve from here.

In 1952, Annie Holleran awaits the stroke of midnight that will mark the exact middle between her fifteenth and sixteenth years, when girls are thought to “ascend.” As local tradition has it, looking into a well when the clock strikes twelve will reveal the face of the boy to whom one will eventually be betrothed. Though she’s been raised calling Sarah Holleran, neé Crowley, Mama, Annie knows—thanks to school yard taunts and whispered conversations that carry through old houses late at night—that her real mother is a woman everyone refers to as her Aunt Juna, a woman she’s never met.

Annie, who shares her birth mother’s blackpool eyes and gift of the know-how, understands enough about what happened when her Aunt Juna left town all those years ago, and how it started a feud between the Hollerans and the nearby Baine family. As her daddy—or the man she’s come to know as her father—drills into her all her life, “If it rattles, choose a different path. If it looks like a Baine, do the same.” She and her younger sister, Caroline, who’s an obvious product of Sarah and John Holleran’s union, only add fire to the long-simmering grudge when they discover the body of old Cora Baine on her property, while Annie reluctantly looks down the Baine well to see her future.

Roy unspools the foundations of the bad blood—and it’s bad enough that it’s gone sour and curdled—between the two families deliciously slowly between the two time periods, though the bulk of the action occurs in 1936, when Juna Crowley accuses Joseph Carl Baine of a terrible crime, leading to the state’s last public hanging. As the jump rope song asks, how many Baines will Juna kill today?

Always the favorite of Cora Baine’s seven boys, the death of Joseph Carl started a mass exodus of Baine men from town, driven out by rumors or fear of Juna Crowley’s powers. But the family never forgot, especially after Juna fell pregnant shortly after Joseph Carl’s hanging.

It doesn’t take more than rudimentary math skills to make the assumption that most of the townsfolk made, egged on by Juna herself, as to the baby’s paternity. And, when Juna abruptly disappears after Annie’s birth, leaving Sarah and her new husband, John to raise the child as their own, the mythos around the legend of Juna Crowley only grows.

There is little joy in the hardscrabble existence Roy’s men and women eke out, particularly in the Depression-era sections, but the familial bond and the blind fierceness to protect one’s own gives an otherwise uncompromisingly bleak story a glimmer of hope. And yet, we still see our hunger for revenge—for blood—reflected back on us in the actions of characters who lived more than 80 years ago, where “children are hoisted onto shoulders because they’ll need to see what happens when a man does wrong.” The power, the one more insidious than anything Juna can muster, is Roy’s ability to craft a world and populate it with characters that “twist a [reader’s] insides this way and that.”

Check our Edgars 2016 HQ page for all our Edgars reviews!

To learn more or order a copy, visit:

opens in a new window![]() opens in a new window

opens in a new window![]() opens in a new window

opens in a new window![]() opens in a new window

opens in a new window![]()

Jordan Foster grew up in a mystery bookstore in Portland, Oregon. She has a MFA in Fiction Writing from Columbia University and currently reviews for Publishers Weekly and Kirkus. She’s back in Portland, where it’s nice and rainy and there are endless places to stash bodies. She tweets @jordanfoster13.

Read all of Jordan Foster’s posts for Criminal Element.