Previously, I wrote an appreciation of Malcolm Braly’s 1961 prison novel Felony Tank as part of my Lost Classics of Noir series for Criminal Element. I singled out the book for being a noteworthy and under-appreciated work of edgy crime fiction, as well as a standout tale about life behind bars. There’s a reason—besides his writing talent—that Braly (1925-1980) wrote so well about his prison life, via Felony Tank and his more celebrated correctional facility novel, On the Yard (1967): he spent the majority of his adult life in penal institutions.

Thanks to Stark House Press’s new reissue of Braly’s 1976 jailhouse memoirs, False Starts: A Memoir of San Quentin and Other Prisons, those of us with an interest in the author can now read his non-fiction account of the penitentiary existence.

False Starts is really more than a prison memoir, despite its subtitle. It’s more like a full autobiography up to that point in the writer’s life. In the first chapter, Braly describes his childhood and early teen years in the parts of California where he was raised, letting us see how, and perhaps why, he drifted into the life of crime that found him detained behind bars for so many of his adult years.

Orphaned as a teenager when his family fell apart and neither biological parent assumed long-term responsibility for his welfare, Braly was rejected by the U.S. Navy when he attempted to enlist at the age of 17, due to a bodily irregularity they discovered in him. At that point, he was going to school and working at a newspaper office, but feeling mostly purposeless and without a family, he became a thief. Eventually, he got caught and was sent to a reform school at age 17, spending most of his time in correctional institutions until he was 40.

In this passage, Braly does some self-analysis in looking at why he might have become a thief and then a prisoner:

It happened, it happened to me, but I feel I also allowed it to happen. Beyond the obvious truth that it was I who committed the burglaries, did them in the euphoric assumption that I couldn’t be caught, I also had the subtle but definite sense I had stood aside and allowed my arrest. In some almost hidden hall of my own house I stood before myself as polar opposites, both accuser and accused . . . Despite my posturing, I was a bright boy, and from this distant vantage it’s difficult to see how I thought I could wear stolen clothes in a town as small as Redding. Perhaps I wanted them so badly I could dismiss what should have been obvious. But darker and more complex, perhaps my father was the authority who had not loved me and I could not and would not abandon this bitter disappointment until I could draw myself to authority – the sheriff – who would love me.

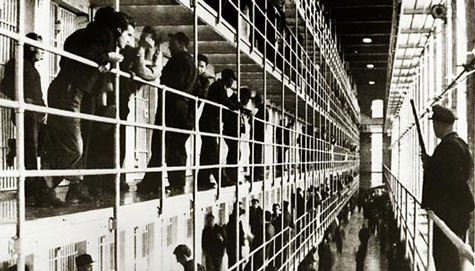

The crux of the book does involve Braly’s reflections on life behind bars, though. Writing mostly about the San Quentin facility where he did most of his time, but also recounting his experiences at reform school and in captivity at Folsom Prison, his words create a vivid picture of how things went in those institutions at those times (approximately 1942-65). We see how the prisoners related to each other, the guards, and other authority figures involved; we get a view of the routines in the detainees’ lives and their mindsets; and we see the pecking order game of who’s boss among them.

The crux of the book does involve Braly’s reflections on life behind bars, though. Writing mostly about the San Quentin facility where he did most of his time, but also recounting his experiences at reform school and in captivity at Folsom Prison, his words create a vivid picture of how things went in those institutions at those times (approximately 1942-65). We see how the prisoners related to each other, the guards, and other authority figures involved; we get a view of the routines in the detainees’ lives and their mindsets; and we see the pecking order game of who’s boss among them.

All of this is shown through the eyes and mind of Braly, a well-read man who quoted various philosophers when offering his reflections on the jailhouse world. Here’s an example of Braly’s reflections on the life of the prisoner:

The hardest part of serving time is the predictability. Each day moves like every other. You know nothing different can happen. You focus on tiny events, a movie scheduled a week ahead, your reclass, your parole hearing, things far in the future, and slowly, smooth day by day, draw them to you. There will be no glad surprise, no spontaneous holiday, and a month from now, six months, a year, you will be just where you are, doing just what you’re doing, except you’ll be older.

. . . Each morning you know where evening will find you. There is no way to avoid your cell . . . Each Monday describes every Friday. Holidays in prison are only another mark of passing time and for many they are the most difficult days. Most of the outrages that provide such lurid passages in the folklore of our prison are inspired by boredom. Some grow so weary of this grinding sameness they will drink wood alcohol even though they are aware this potent toxin may blind or kill them. Others fight with knives to the death and the survivor will remark, “It was just something to do.”

In some respects, False Starts reads like a novel—specifically a thriller. There are exhilarating descriptions of prison breaks (Braly was involved in more than one), standoffs between criminals and lawmen, adventures of thieves who are on the run from authorities, and robbery jobs. Braly’s recounting of these episodes can bring a reader the same kinds of thrills one gets from poring through a particularly bracing crime novel. Braly, whose crimes mostly involved robberies—some of the armed variety—writes about his criminal exploits in a way that is somehow both dispassionate and thrill inducing.

For me, the most interesting part of the memoirs is the time when Braly was released from his first sentence in San Quentin. He was 26, free (albeit on parole), and living in San Francisco. He was a bright young guy with an artistic mindset (Braly was a painter and musician, in addition to his writing) in a big city that seems a good place for a creative type. You’d think/hope that all the soul-deadening prison time would have convinced him to try and play things straight thhis time and make a life for himself in San Francisco.

But Braly, although then married, soon to be a father, and having no trouble finding gainful employment (low-paying odd jobs, but still . . .), just couldn’t—or wouldn’t—stop stealing. Soon enough, he got caught again and sent right back to San Quentin, then on to Folsom, and then back to San Quentin.

I’m not going to attempt to analyze young Braly and say why I think he kept stealing then—that’s something other readers can do for themselves with the aid of Braly’s own thoughts on the matter, if they care to. But Braly’s drifting back into a life of crime at that stage of his existence is something I find head-scratchingly interesting.

At age 31, Braly was paroled for a second time. When he describes the life he led as a free man in San Francisco at that time, readers familiar with his 1963 classic work of beatnik pulp fiction, Shake Him Till He Rattles, will see parallels between the setting and characters of the novel and what Braly lived in this brief period. This era of existence in the open world was short-lived, however, as Braly returned to his thieving exploits, got nabbed yet again, and soon found himself in the familiar confines of San Quentin prison.

This is when he started writing in earnest—in False Starts, he tells about writing Felony Tank, Shake Him Till He Rattles, and On the Yard from prison, the jubilating experience of getting his first publishing contact (with Fawcett’s Gold Medal books line), and the life-changing circumstance of coming under the patronage of famed editor/literary agent Knox Burger.

All told, False Starts is an engaging book that is a natural for anyone who’s interested in Malcolm Braly. And, whether or not you care about Braly, it should work for anybody who would like to read a reflective, painfully honest account of prison life. Stark House’s new edition comes with a 22-page introduction by Rick Ollerman.

Brian Greene writes short stories, personal essays, and feature articles and reviews on/of books, music, and film. His work has appeared in over 25 publication since 2008. He has also written about crime fiction and films for Noir Originals, Paperback Parade, Mulholland Books, Crime Time, Crimeculture, Stark House Press, and The Life Sentence. Brian lives in Durham, North Carolina. He can be found on Twitter @brianjoebrain